Issue 32 - June 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Name Identifies You in a Unique Way, Not Just Your Physical Self, but Who You Are As Person

CHOOSING A CONFIRMATION NAME. A name identifies you in a unique way, not just your physical self, but who you are as person. One of the traditional practices in the Church at the time of Confirmation is choosing a name that will remind you of this sacrament. Your prayerful reflection will help you determine that name. You might want to recommit yourself to your baptismal name since it expresses the relationship that exist between these two sacraments, especially after you reflect on its meaning and discover some of the people who shared your name in Christian history. You might want to choose the name of a saint who represents the type of Cristian you wish to be. It is important to learn as much as you can about your patron saint. After all, you are asking this saint to be your friend and advocate for the rest of your life. Whether you decide to stay with your baptismal name or pick a new name, take the time to research and explore the root meaning of the name, for as Scripture says: “Yahweh calls each of us by name”. One of the most beautiful parts of your journey towards confirmation is choosing a patron saint, one of the great saints of our Church whose life in Christ is one that inspires you and calls you to be an ardent and radiant catholic. The saint are not just people who lived long ago! Moreover, they are alive in heaven now, totally present in our lives through God’s grace and their prayers. -

St. Francis De Sales Catholic Community June 14, 2020

St. Francis de Sales Catholic Community June 14, 2020 Parish Established 1902 109 Main Street, Phoenicia, NY 12464 Rectory: 845-688-5617 • Fax: 845-688-5630 www.stfrancisdesalesphoenicia.com Email: [email protected] MASS SCHEDULE Saturday: 5:00 pm Sunday: 10:00 am Daily: 8:00 am (Mon–Thurs) Holy Day of Obligation Eve: 5:00 pm Holy Day: 9:00 am & 7:00 pm Rev. Raphael Iannone, O.F.M., Cap, Priest in Attendance [email protected] Rev. Thomas P. Kiely, Parish Administrator Gem of the Catskills 845-679-7696 Rev. Christopher Berean, Parish Administrator PARISH COUNCIL 845-217-3333 Meets at the rectory at 7:00 pm every six weeks. Check the bulletin for exact dates. HOLY SACRAMENTS ALL ARE WELCOME! Sacrament of Baptism Pres. Pat Ruane: 688-5357 By appointment. Prior instruction required. Parish Council Secretary: Joline Streiff Sacrament of Matrimony Fr. Raphael Iannone, O.F.M., Cap.: 688-5617 By appointment 6 months before wedding PARISH COUNCIL LEADERS Sacrament of Reconciliation Bldg & Grounds: Burr Hubbell……. .............. 750-3203 Saturdays 4:30 pm to 5:00 pm (and by appointment) Cemetery Mgr: Mark Wilsey .......................... 688-5500 [ Anointing of the Sick and Communication: Pam Hammond .................... 688-2642 Communion to the Homebound Director of Music: Dennis Yerry… ................ 853-3394 Call the Rectory to make arrangements Emerg. Relief Committee: Ed Ullmann .......... 688-5874 Religious Education Program: Gerry Nilsen ... 687-9769 RELIGIOUS EDUCATION PROGRAM Finance: Mike Ruane...................................... 688-5357 Religious Education and Adult Faith Formation schedules Liturgy: Contact Father Raphael ..................... 688-5617 are posted in our bulletins and on the parish website. -

A Multidimensional Model for the Vernacular: Linking Disciplines and Connecting the Vernacular Landscape to Sustainability Challenges

sustainability Article A Multidimensional Model for the Vernacular: Linking Disciplines and Connecting the Vernacular Landscape to Sustainability Challenges Juanjo Galan 1,* , Felix Bourgeau 1 and Bas Pedroli 2 1 Department of Architecture, Aalto University, 02150 Espoo, Finland; felix.bourgeau@aalto.fi 2 Department of Environmental Sciences, Wageningen University, 6708 Wageningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 June 2020; Accepted: 3 August 2020; Published: 6 August 2020 Abstract: After developing a systematic analysis of the vernacular phenomenon in different disciplines, this paper presents a flexible model to understand the multiple factors and the different degrees of vernacularity behind the many processes that lead to the generation of material culture. The conceptual model offers an open, polythetic and integrative approach to the vernacular by assuming that it operates in different dimensions (temporal, socio-political, sociological, locational, epistemological, procedural, economic and functional), and that the many attributes or characteristics included in those dimensions are all relevant but not strictly necessary. The model is intended to facilitate a more methodical and rigorous connection between the vernacular concept and contemporary discourses on sustainability, resilience, globalization, governance, and rural-urban development. In addition, and due to its transdisciplinary character, the model will enable the development of comparative studies within and between a wide range of fields (architecture, landscape studies, design, planning and geography). A prospective analysis of the use of the model in rural landscapes reveals its potential to mediate between the protective approach that has characterized official planning during the last decades and emergent approaches that advocate the reinterpretation of the vernacular as a new form to generate new collective identities and to reconnect people and place. -

I. the Easter Vigil II. Holy Days of Obligation III. Special Celebrations for Dioceses and Parishes IV

Liturgical Calendar Notes I. The Easter Vigil II. Holy Days of Obligation III. Special Celebrations for Dioceses and Parishes IV. Rogation Day Prayer Service The Easter Vigil The first Mass of Easter, the Easter Vigil, falls between nightfall of Holy Saturday and daybreak of Easter Sunday. The General Norms for the Liturgical Year and the Calendar, no 21, states: The Easter Vigil, during the holy night when Christ rose from the dead, ranks as the “mother of all vigils.” Keeping watch, the Church awaits Christ’s resurrection and celebrates it in the sacraments. Accordingly, the entire celebration of this vigil should take place at night, that is, it should either begin after nightfall or end before the dawn of Sunday. Individual parishes can check the following website to determine nightfall in their area: http://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/docs/RS_OneDay.html On this website, nightfall is listed as “End civil twilight.” Liturgical Calendar Notes 1 Holy Days of Obligation On December 13, 1991 the members of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops of the United States of American made the following general decree concerning holy days of obligation for Latin rite Catholics: In addition to Sunday, the days to be observed as holy days of obligation in the Latin Rite dioceses of the United States of America, in conformity with canon 1246, are as follows: January 1, the solemnity of Mary, Mother of God Thursday of the Sixth Week of Easter, the solemnity of the Ascension (observed on the 7th Sunday of Easter in Kentucky Dioceses) August 15, the solemnity of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary November 1, the solemnity of All Saints December 8, the solemnity of the Immaculate Conception December 25, the solemnity of the Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ Whenever January 1, the solemnity of Mary, Mother of God, or August 15, the solemnity of the Assumption, or November 1, the solemnity of All Saints, falls on a Saturday or on a Monday, the precept to attend Mass is abrogated. -

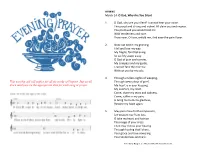

Vespers Program Print 31MAR

HYMNS March 24: O God, Why Are You Silent 1. O God, why are you silent? I cannot hear your voice. The proud and strong and violent All claim you and rejoice. You promised you would hold me With tenderness and care. Draw near, O Love, enfold me, And ease the pain I bear. 2. Now lost within my grieving, I fall and lose my way. My fragile, faint believing So swiftly swept away. O God of pain and sorrow, My compass and my guide, I cannot face the morrow Without you by my side. 4. Through endless nights of weeping, This worship aid will suffice for all six weeks of Vespers. Just scroll Through weary days of grief, down until you see the appropriate date for each song or prayer. My heart is in your keeping, My comfort, my relief. Come, share my tears and sadness, Come, suffer in my pain; O bring me home to gladness, Restore my hope again. 5. May pain draw forth compassion, Let wisdom rise from loss. O take my heart and fashion The image of your cross. Then may I know your healing Through healing that I share, Your grace and love revealing Your tenderness and care. Text: Marty Haugen, b. 1950, © 2003, GIA Publications, Inc. EVENING THANKSGIVING PSALMS Each night, we begin with Psalm 141, and incense is placed in the censer to suggest our prayers rising to God. At the end of this and each psalm, there is a prayer by the presider. Every night: Psalm 141 Evening Offering March 31: Psalm 23 Shepherd Me, O God READING MAGNIFICAT (next page) INTERCESSIONS THE LORD’S PRAYER CLOSING PRAYER Presider: Our help is in the name of the Lord. -

Quality Silversmiths Since 1939. SPAIN

Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com - ARTIMETAL - PROCESSIONALIA 2014-2015 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN ARTISTIC SILVER INDEXINDEX Presentation ......................................................................................... Pag. 1-12 ARTISTIC SILVER - ARTIMETAL ARTISTICPresentation SILVER & ARTIMETAL Pag. 1-12 ChalicesChalices && CiboriaCiboria ........................................................................... Pag. 13-6713-52 MonstrancesCruet Sets & Ostensoria ...................................................... Pag. 68-7853 TabernaclesJug & Basin,........................................................................................... Buckets Pag. 79-9654 AltarMonstrances accessories & Ostensoria Pag. 55-63 &Professional Bishop’s appointments Crosses ......................................................... Pag. 97-12264 Tabernacles Pag. 65-80 PROCESIONALIAAltar accessories ............................................................................. Pag. 123-128 & Bishop’s appointments Pag. 81-99 General Information ...................................................................... Pag. 129-132 ARTIMETAL Chalices & Ciboria Pag. 101-115 Monstrances Pag. 116-117 Tabernacles Pag. 118-119 Altar accessories Pag. 120-124 PROCESIONALIA Pag. 125-130 General Information Pag. 131-134 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. Justo Dorado, 12 28040 Madrid, Spain Product design: Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. CHALICES & CIBORIA Our silversmiths combine -

1 Introduction Two Processions Entered Jerusalem on a Spring Day

1 Davidson College Presbyterian Church Davidson, North Carolina Scott Kenefake, Interim Senior Pastor “The Last Week” Palm Sunday March 25, 2018 Introduction Two processions entered Jerusalem on a spring day in the year 30. It was the beginning of the week of Passover, the most sacred week of the Jewish year. One was a peasant procession, the other an imperial procession. From the east, Jesus rode a donkey down the Mount of Olives, cheered by his followers. Jesus was from the peasant village of Nazareth, his message was about the kingdom of God, and his followers came from the peasant class. They had journeyed to Jerusalem from Galilee, about a hundred miles to the north. On the opposite side of the city, from the west, Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Idumea, Judea, and Samaria, entered Jerusalem at the head of a column of imperial cavalry and soldiers. Jesus’s procession proclaimed the kingdom of God; Pilate’s proclaimed the power of empire. The two processions embody the central conflict of the week that led to Jesus’s crucifixion. Pilate’s military procession was a demonstration of both Roman Imperial power—imagine cavalry on horses, foot soldiers, leather armor, helmets, weapons, banners, golden eagles mounted on poles, sun glinting on metal and gold. Sounds: the marching of feet, the creaking of leather, and the clinking of bridles, the beating of drums. The swirl of dust. The eyes of the silent onlookers, some curious, some awed, some resentful--and Roman Imperial Theology—they called Caesar (in this case Tiberius) “son of God,” “lord,” and “savior.” Inscriptions refer to him as … one who had brought “peace on earth.” Though unfamiliar to most people today, the imperial procession was well known in the Jewish homeland in the first century …, for it was the standard practice of the Roman governors of Judea to be in Jerusalem for the major Jewish festivals. -

The Vernacular in Christian Worship Walter E

ella The Vernacular In Christian Worship Walter E. Buslin VOL.. 91, N'O. 4 WINTER, 1965 CAECILIA Published four times a year, Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Second-Class Postage Paid at Omaha, Nebraska Subscription Price--~3.00 per year All articles for publication must be in the hands of the editor, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska, 30 days before month of publication. Business Manager: Norbert Letter Change of address should be sent to the circulation manager: Paul Sing, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska Postmaster: Fonn 3579 to Caecilia, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebr. caeci la fllUmiJHJJ nt tJ11JwliL t1whdL rrt.uAiL TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorials ,->-- __ • • •• _•• _. -_"_ ••• • __ •• •. __ •• -_ •. .' '. __ . _. __ 135 The Vernacular in Christian Worship-Walter E. Buszin ~ . .. _ 141 'Johannes de Tinetoris-Richard J. Schuler .-. .__ . ._. 143 Review Books .__ ._. ._. _.. _..... __ .. __ .. __ ... ._. ._.. .. .. '_. __ "_.__ - --_---__ 148 Music .. ._._. _., __ _. .. ._ __ ._ .. _ __ .__ ._._ .. .__ .__ -_.. -- .__ ---. __ -_- ._ 151 News-Litter 156 VOL. 91, NO. 4 WINTER, 1965 CAECILIA A Quarterly Review devoted to the liturgical music apostolate. Published with ecclesiastical approval by· the Society of Saint Caecilia in Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Established in 1874 by John B. Singenberger, K.C.S.G., K.C.S.S. (1849-1924). Editor ---------------- Very Rev. Msgr. Francis P. Schmitt CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Francis A. Brunner, C.Ss.R. Elmer Pfeil Louise Cuyler Richard Schuler David Greenwood Lavern Wagner Paul Koch Roger Wagner Paul Manz Abbot Rembert Weakland, O.S.B. -

The Offering of Incense) Thurification Or Incensation Is an Expression of Reverence and of Prayer, As Is Signified in Sacred Scripture…Psalm 141; Revelation 8:3 1

Thurifer Procedures Preparing for Mass *Attire…dress as you would…when serving as Acolyte *Arrive inside church at a minimum 45 minutes before the start of Mass. *Position Censer Stand near Ambo/Lectern/Pulpit. You will need easy access to return boat before Gospel reading. Gather the following in Sacristy: *Thurible… (Metal censer suspended from chains) --Contains 4 items: Base; Tray; Top; Chains --If necessary, you may need to clean out any unburnt coals from the tray. You can dispense the coals directly in to the trash…please insure coals have been cooled. If not…place in sink, flow water over them. --Lighter…make certain it flames --Boat…contains the incense. Fill boat with incense --Spoon…position spoon in boat --Charcoal…2 discs Lighting of charcoal…10 minutes prior to start of Mass or Procession Service --Use tongs...with Star facing down…hold charcoal disc below countertop level. --Place lighter on underside of disc…the charcoal will flare…sparks will come off disc…continue to light until sparks have stopped. Slightly blow on disc to insure it is burning --Place charcoal disc inside tray…star side facing up. --Place charcoal discs side by side…not on top of each other --close top…exit Sacristy…start to ‘swing’ thurible Incensation (The offering of Incense) Thurification or Incensation is an expression of reverence and of prayer, as is signified in Sacred Scripture…Psalm 141; Revelation 8:3 1. During the entrance procession; 2. At the beginning of Mass; to incense the cross and the altar; 3. At the procession before the Gospel and the proclamation of the Gospel itself; 4. -

Historical Notes on the Canon Law on Solemnized Marriage

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 2 Number 2 Volume 2, April 1956, Number 2 Article 3 Historical Notes on the Canon Law on Solemnized Marriage William F. Cahill, B.A., J.C.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The nature and importance of the Catholic marriage ceremony is best understood in the light of historicalantecedents. With such a perspective, the canon law is not likely to seem arbitrary. HISTORICAL NOTES ON THE CANON LAW ON SOLEMNIZED MARRIAGE WILLIAM F. CAHILL, B.A., J.C.D.* T HE law of the Catholic Church requires, under pain of nullity, that the marriages of Catholics shall be celebrated in the presence of the parties, of an authorized priest and of two witnesses.1 That law is the product of an historical development. The present legislation con- sidered apart from its historical antecedents can be made to seem arbitrary. Indeed, if the historical background is misconceived, the 2 present law may be seen as tyrannical. This essay briefly states the correlation between the present canons and their antecedents in history. For clarity, historical notes are not put in one place, but follow each of the four headings under which the present Church discipline is described. -

Liturgical Calendar 2007 for the Dioceses of the United States of America

LITURGICAL CALENDAR 2007 FOR THE DIOCESES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Committee on the Liturgy United States Conference of Catholic Bishops 2 © 2006 United States Conference of Catholic Bishops 2 3 Introduction Each year the Secretariat for the Liturgy of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops publishes the Liturgical Calendar for the Dioceses of the United States of America. This calendar is used by authors of ordines and other liturgical aids published to foster the celebration of the liturgy in our country. The calendar is based upon the General Roman Calendar, promulgated by Pope Paul VI on February 14, 1969, subsequently amended by Pope John Paul II, and the Particular Calendar for the Dioceses of the United States of America, approved by the National Conference of Catholic Bishops.1 The General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 2002, reminds us that in the cycles of readings and prayers proclaimed throughout the year in the sacred liturgy “the mysteries of redemption are recalled in the Mass in such a way that they are in some way made present.” Thus may each celebration of the Holy Eucharist which is served by this calendar be for the Church in all the dioceses of the United States of America “ the high point of the action by which God sanctifies the world in Christ and of the worship that the human race offers to the Father, adoring him through Christ, the Son of God, in the Holy Spirit.”2 Monsignor James P. Moroney Executive Director USCCB Secretariat for the Liturgy 1 For the significance of the several grades or kinds of celebrations, the norms of the Roman Calendar should be consulted (cf. -

Sarum Calendar 2018

Sarum Kalenday 2018 AD. Year 2-G. JANUARY [PICA] Circumcision of Our Lord. Lesser 1 Mon Double ix. Lessons. Octave of S. Stephen, Double 2 Tues Invitatory, iii. Lessons with Rulers of the Choir. Octave of S. John. Double Invitatory, 3 Wed iii. Lessons, with Rulers of the Choir. Octave of the Holy Innocents, 4 Thur Double Invitatory, iii. Lessons, with Rulers of the Choir. Vigil. 5 Fri Mem. of the Octave of S. Thomas. Mem. S. Edward, Conf. Epiphany of Our Lord. Principal Of the Feast. 6 Sat Double Feast, ix. Lessons. Sunday within the Octave of the 7 Sun The Keys of Septuagesima. Epiphany Lucian, Priest, and Comps., Marts. Mem. Of the Octave. 8 Mon only. 9 Tues Of the Octave. 10 Wed Of the Octave. 11 Thur Sun in Aquarius. Of the Octave. 12 Fri Of the Octave. Octave of the Epiphany. ix. Lessons. Of the Octave. 13 Sat Triple Invit. Middle Lessons of S. Hilary. First Sunday after the Octave of S. Felix, Priest and Mart. iii. 14 Sun the Epiphany. Lessons. Domine ne in ira . mem, middle lessons of Felix. Lauds all ants. S. Maurus, Abbot and Conf. iii. 15 Mon Lessons. S. Marcellus, Pope and Mart. iii. Commemoration. 16 Tues Lessons. S. Sulpicius, Bp. and Conf. iii. Commemoration. 17 Wed Lessons. 18 Thur S. Prisca, Virg. and Mart. iii. Lessons. Commemoration. S. Wulfstan, Bp. and Conf. ix. 19 Fri Lessons. SS. Fabian and Sebastian, Marts., ix. 20 Sat Lessons. no exposition. Second Sunday after the Octave of S. Agnes, Virg. and Mart. ix. Lessons.