West Indian Iguanas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclura Or Rock Iguanas Cyclura Spp

Cyclura or Rock Iguanas Cyclura spp. There are 8 species and 16 subspecies of Cyclura that are thought to exist today. All Cyclura species are endangered and are listed as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Appendix I, the highest level of pro- tection the Convention gives. Wild Cyclura are only found in the Caribbean, with many subspecies endemic to only one particular island in the West Indies. Cyclura mature and grow slowly compared to other lizards in the family Iguani- dae, and have a very long life span (sometimes reaches ages of 50+ years). The more common species in the pet trade in- clude the Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta cornuta), and Cuban Rock Iguana (juvenile), the Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila nubila). Cyclura nubila nubila Basic Care: Habitat: Cyclura care is similar to that of the Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), but there are some major differences. Cyclura Iguanas are generally ground-dwelling lizards, and require a very large cage with lots of floor space. The suggested minimum space to keep one or two adult Cyclura in captivity is usually a cage that is at the very least 10’X10’. Because of this space requirement, many cyclura owners choose to simply des- ignate a room of their home to free-roaming. If a male/female pair are to be kept to- gether, multiple basking spots, feeding stations, and hides will be required. All Cyclura are extremely territorial and can inflict serious injuries or even death to their cage- mates unless monitored carefully. The recommended temperature for Cyclura is a basking spot of about 95-100F during the day, with a temperature gradient of cooler areas to escape the heat. -

Chuckwalla Habitat in Nevada

Final Report 7 March 2003 Submitted to: Division of Wildlife, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State of Nevada STATUS OF DISTRIBUTION, POPULATIONS, AND HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS OF THE COMMON CHUCKWALLA, Sauromalus obesus, IN NEVADA Principal Investigator, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2485 Co-Principal Investigator, Thomas C. Edwards, Jr., Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5210 (435)797-2509 Research Associate, Paul C. Ustach, Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2450 1 INTRODUCTION As a primary consumer of vegetation in the desert, the common chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus (=ater; Hollingsworth, 1998), is capable of attaining high population density and biomass (Fitch et al., 1982). The 21 November 1991 Federal Register (Vol. 56, No. 225, pages 58804-58835) listed the status of chuckwalla populations in Nevada as a Category 2 candidate for protection. Large size, open habitat and tendency to perch in conspicuous places have rendered chuckwallas particularly vulnerable to commercial and non-commercial collecting (Fitch et al., 1982). Past field and laboratory studies of the common chuckwalla have revealed an animal with a life history shaped by the fluctuating but predictable desert climate (Johnson, 1965; Nagy, 1973; Berry, 1974; Case, 1976; Prieto and Ryan, 1978; Smits, 1985a; Abts, 1987; Tracy, 1999; and Kwiatkowski and Sullivan, 2002a, b). Life history traits such as annual reproductive frequency, adult survivorships, and population density have all varied, particular to the population of chuckwallas studied. Past studies are mostly from populations well within the interior of chuckwalla range in the Sonoran Desert. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

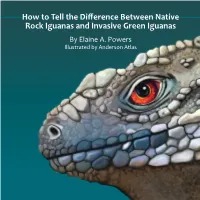

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard (2012)

FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard Marine and Coastal Spatial Data Subcommittee Federal Geographic Data Committee June, 2012 Federal Geographic Data Committee FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard, June 2012 ______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Need ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Scope ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Application ............................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Relationship to Previous FGDC Standards .............................................................. 4 1.6 Development Procedures ......................................................................................... 5 1.7 Guiding Principles ................................................................................................... 7 1.7.1 Build a Scientifically Sound Ecological Classification .................................... 7 1.7.2 Meet the Needs of a Wide Range of Users ...................................................... -

Volcanoes & Land Iguanas

Volcanoes & Land Iguanas 1/2 Background Galapagos iguanas are thought to of arrived in the Galapagos archipelago by floating on of rafts of vegetation from the South American continent. It is estimated that a split of iguana species into Land and Marine Iguanas occurred around 10.5 million years ago. In Galapagos, 3 species of land Iguanas now exist. The Land Iguanas include: Conolophus subcristatus (found on 6 islands), Conolophus pallidus (found only on Santa Fe Island) and a third species Conolophus rosada (known for its pink colour) is found on Wolf volcano on Isabela Island. Habitat Land Iguanas are found in the drier areas of the island. Being cold- blooded, to keep warm they bask in the sun and on the volcanic rock, escaping the midday sun by finding shade under vegetation and rocks, and sleeping in burrows to conserve their body heat. Land Iguanas feed on vegetation such as fallen fruits and cactus pads and even the spines of prickly pear © David cactus. Phillips © Galapagos Conservation © Cyder Trust Volcanoes & Land Iguanas 2/2 Reproduction Between 6 and 10 years of age, male Land Iguanas become highly aggressive, fighting for the attention of the female Land Iguanas. Mating then takes place at the end of the year and eggs are usually laid between January and March (June on Fernandina!). However, in order to lay these eggs female Land Iguanas have no option but to scale to the summit of volcanoes. © Phil Herbert The Volcanic Importance Every pregnant female will need to find a patch of volcanic ash; these pockets of warm soft soil are perfect for the incubation of their eggs; however these sites are difficult to come by. -

Chemical Signatures of Femoral Pore Secretions in Two Syntopic but Reproductively Isolated Species of Galápagos Land Iguanas (Conolophus Marthae and C

www.nature.com/scientificreports open chemical signatures of femoral pore secretions in two syntopic but reproductively isolated species of Galápagos land iguanas (Conolophus marthae and C. subcristatus) Giuliano colosimo1,2, Gabriele Di Marco2, Alessia D’Agostino2, Angelo Gismondi2, Carlos A. Vera3, Glenn P. Gerber1, Michele Scardi2, Antonella Canini2 & Gabriele Gentile2* the only known population of Conolophus marthae (Reptilia, Iguanidae) and a population of C. subcristatus are syntopic on Wolf Volcano (Isabela Island, Galápagos). No gene fow occurs suggesting that efective reproductive isolating mechanisms exist between these two species. Chemical signature of femoral pore secretions is important for intra- and inter-specifc chemical communication in squamates. As a frst step towards testing the hypothesis that chemical signals could mediate reproductive isolation between C. marthae and C. subcristatus, we compared the chemical profles of femoral gland exudate from adults caught on Wolf Volcano. We compared data from three diferent years and focused on two years in particular when femoral gland exudate was collected from adults during the reproductive season. Samples were processed using Gas Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS). We identifed over 100 diferent chemical compounds. Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (nMDS) was used to graphically represent the similarity among individuals based on their chemical profles. Results from non-parametric statistical tests indicate that the separation between the two species is signifcant, suggesting that the chemical profle signatures of the two species may help prevent hybridization between C. marthae and C. subcristatus. Further investigation is needed to better resolve environmental infuence and temporal reproductive patterns in determining the variation of biochemical profles in both species. -

ARAV Cancer and Case Reports

Section 20 ARAV Cancer and Case Reports Jeff Baier, MS, DVM; Erica Giles, DVM Moderators Fibropapillomatosis in Chameleons Kim Oliver Heckers, Dr med vet, Janosch Dietz, med vet, Rachel E Marschang, PD, Dr med vet, Dipl ECZM (Herpetology), FTÄ Mikrobiologie, ZB Reptilien Session #346 Affiliation: Laboklin GmbH & Co KG, Steubenstr 4, 97688 Bad Kissingen, Germany. Fibropapillomas have been observed with increasing frequency in recent years and occur mostly in panther chameleons (Furcifer pardalis). These include a complex of different neoplastic lesions (papillomas, keratoacan- thomas and intracutaneous cornifying epitheliomas) with similar macroscopic appearance and clinical behavior characterized by nodular changes, starting with single spots, which spread over the body in a period of 1-2 years. At the beginning, the overall general condition is good while at progressive stages of spread, the general condi- tion declines. In a retrospective study, 22 tumors from chameleons with several types of fibropapillomas were examined. Panther chameleons (Furcifer pardalis) were the most affected species (64%), followed by veiled chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus) (14%) and 22% of chameleons of unknown species. All of the affected chameleons were adults. The age of 9 animals was known and had a range of 2-5 years with an average of 3.4 years. Thirteen males, one female and eight chameleons of unknown sex were examined. Papillomas were the most frequent tumors (55%), followed by keratoacanthomas (36%) and intracutaneous cornifying epitheliomas (9%). In this study no trend towards malignant transformation of the tumors was found. The etiology of fibro- papillomatosis is still unknown but a viral genesis is suspected. An invertebrate iridovirus was detected in the lesions of one veiled chameleon by PCR. -

Sauromalus Hispidus

ARTÍCULOS CIENTÍFICOS Cerdá-Ardura & Langarica-Andonegui 2018 - Sauromalus hispidus in Rasa Island- p 17-28 ON THE PRESENCE OF THE SPINY CHUCKWALLA SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) IN RASA ISLAND, MEXICO PRESENCIA DEL CHACHORÓN ESPINOSO SAUROMALUS HISPIDUS (STEJNEGER, 1891) EN LA ISLA DE RASA, MÉXICO Adrián Cerdá-Ardura1* and Esther Langarica-Andonegui2 1Lindblad Expeditions/National Geographic. 2Facultad de Ciencias, Uiversidad Nacional Autónoma de México, CDMX, México. *Correspondence author: [email protected] Abstract.— In 2006 and 2013 two different individuals of the Spiny Chuckwalla (Sauromalus hispidus) were found on the small, flat, volcanic and isolated Rasa Island, located in the Midriff Region of the Gulf of California, Mexico. This species had never been recorded from Rasa Island prior to 2006. A new field study in 2014 revealed the presence of a single female chuckwalla inhabiting the Tapete Verde Valley, in the south-central part of the island, occupying a territory no bigger than 10000 m2. A scat analysis shows that the only food consumed by the animal is the Alkali Weed (Cressa truxilliensis) that forms patches of carpets in its habitat. The individual is in precarious condition, as it seems to starve on a seasonal basis, especially during El Niño cycles; also, it is missing fingers and toes, which appear to be intentional markings by amputation. We conclude that the two individuals were introduced to the island intentionally by humans. Keywords.— Chuckwalla, Gulf of California, Rasa Island. Resumen.— En 2006 y 2013 se encontraron dos individuos diferentes del cachorón de roca o chuckwalla espinoso (Sauromalus hispidus) en la pequeña, plana, volcánica y aislada isla Rasa, localizada en la Región de las Grandes Islas, en el Golfo de California, México. -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura Cornuta Cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789)

HUSBANDRY GUIDELINES: RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura cornuta cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789) REPTILIA: IGUANIDAE Compiler: Cameron Candy Date of Preparation: DECEMBER, 2009 Institute: Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond, NSW, Australia Course Name/Number: Certificate III in Captive Animals - 1068 Lecturers: Graeme Phipps - Jackie Salkeld - Brad Walker Husbandry Guidelines: C. c. cornuta 1 ©2009 Cameron Candy OHS WARNING RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura c. cornuta RISK CLASSIFICATION: INNOCUOUS NOTE: Adult C. c. cornuta can be reclassified as a relatively HAZARDOUS species on an individual basis. This may include breeding or territorial animals. POTENTIAL PHYSICAL HAZARDS: Bites, scratches, tail-whips: Rhinoceros Iguanas will defend themselves when threatened using bites, scratches and whipping with the tail. Generally innocuous, however, bites from adults can be severe resulting in deep lacerations. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of injury from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - Keep animal away from face and eyes at all times - Use of correct PPE such as thick gloves and employing correct and safe handling techniques when close contact is required. Conditioning animals to handling is also generally beneficial. - Collection Management; If breeding is not desired institutions can house all female or all male groups to reduce aggression - If aggressive animals are maintained protective instrument such as a broom can be used to deflect an attack OTHER HAZARDS: Zoonosis: Rhinoceros Iguanas can potentially carry the bacteria Salmonella on the surface of the skin. It can be passed to humans through contact with infected faeces or from scratches. Infection is most likely to occur when cleaning the enclosure. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of infection from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - ALWAYS wash hands with an antiseptic solution and maintain the highest standards of hygiene - It is also advisable that Tetanus vaccination is up to date in the event of a severe bite or scratch Husbandry Guidelines: C. -

A Review on Presence of Oleanolic Acid in Natural Products

Natura Proda Medica, (2), April 2009 64 A review on presence of Oleanolic acid in Natural Products A review on presence of Oleanolic acid in Natural Products YEUNG Ming Fai Abstract Oleanolic acid (OA), a common phytochemical, is chosen as an example for elucidation of its presence in natural products by searching scientific databases. 146 families, 698 genera and 1620 species of natural products were found to have OA up to Sep 2007. Keywords Oleanolic acid, natural products, plants, Chinese medicine, Linnaeus system of plant classification Introduction and/or its saponins in natural products was carried out for Oleanolic acid (OA), a common phytochemical, is chosen elucidating its pressence. The classification was based on as an example for elucidation of its presence in natural Linnaeus system of plant classification from the databases of products by searching scientific databases. SciFinder and China Yearbook Full-text Database (CJFD). Methodology of Review Result of Review Literature search for isolation and characterization of OA Search results were tabulated (Table 1). Table 1 Literature review of natural products containing OA and/or its saponins. The classification is based on Angiosperm Phylogeny Group APG II system of plant classification from the databases of SciFinder and China Yearbook Full-text Database (CJFD). Family of plants Plant scientific names Position of plant to be Form of OA References isolated isolated Acanthaceae Juss. Acanthus illicifolius L. Leaves OA [1-2] Acanthaceae Avicennia officinalis Linn. Leaves OA [3] Acanthaceae Blepharis sindica Stocks ex T. Anders Seeds OA [4] Acanthaceae Dicliptera chinensis (Linn.) Juss. Whole plant OA [5] Acanthaceae Justicia simplex Whole plant OA saponins [6] Actinidiaceae Gilg.