Review of My Journey As a Witness – Shahidul Alam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Legacy of Virtue the Government Can't Silence: The

A Legacy of Virtue the Government Can’t Silence: The Case of Shahidul Alam The job for media pundits and intellectuals is often to question black and white narratives that are, in reality; washed in greys. But there are other times when things aren’t so complicated. There are times when one side clearly stands for inclusivism, creativity, empathy, mercy, mirth, humor, compassion and an unabashed zeal for the act of living, while the other side represents grim, cynical, self-interested raw power perpetuated by those who use violence to cover their insecurities, fears and incapacity to see that one’s reason for living on this earth has nothing to do with the allure of power and control. The arrest of renowned photographer Shahidul Alam by the Bangladeshi government is one these times. Alam, 63, was detained on Aug. 5, 2018, by plain-clothed officers who identified themselves as the detective branch of the Bangladeshi government. He was charged under the Section 57 Information and Communication Technology Act (ICT) with “spreading propaganda and false information used against a government” and for making “provocative comments” about the government’s violent response to students protesting for safer roads, in an interview he conducted with Al Jazeera. He was arrested hours after the interview. Bangladeshi’s ruling government, the Awami League, has consistently used Section 57 as a legal bludgeon to silence critics. The Bangladeshi court rejected Alam’s bail plea on Sept. 11 and he remains imprisoned. The protests, which started in Dhaka but spread throughout the country, began after a private bus ran over a group of college students, killing two. -

Investment Corporation of Bangladesh Human Resource Management Department List of Valid Candidates for the Post of "Cashier"

Investment Corporation of Bangladesh Human Resource Management Department List of valid candidates for the post of "Cashier" Sl. No Tracking No Roll Name Father's Name 1 1710040000000003 16638 MD. ZHAHIDUL ISLAM SHAHIN MD. SAIFUL ISLAM 2 1710040000000006 13112 MD. RATAN ALI MD. EBRAHIM SARKAR 3 1710040000000007 09462 TANMOY CHAKRABORTY BHIM CHAKRABORTY 4 1710040000000008 01330 MOHAMMAD MASUDUR LATE MOHAMMAD CHANDMIAH RAHMAN MUNSHI 5 1710040000000009 17715 SUSMOY. NOKREK ASHOK.CHIRAN 6 1710040000000012 14054 OMAR FARUK MD. GOLAM HOSSAIN 7 1710040000000013 17910 MD. BABAR UDDIN ANSARUL HOQ 8 1710040000000015 13444 SHAKIL JAINAL ABEDIN 9 1710040000000016 19905 ASIM BISWAS ANIL CHANDRA BISWAS 10 1710040000000017 21002 MD.MAHMUDUL HASAN MD.RAFIQUL ISLAM 11 1710040000000019 19973 MD.GOLAM SOROWER MD. SHOHRAB HOSSIN 12 1710040000000020 19784 MD ROKIBUL ISLAM MD OHIDUR RAHMAN 13 1710040000000021 17365 MD. SAIFUL ISLAM MOHAMMAD ALI 14 1710040000000022 17634 MD. ABUL KALAM AZAD MD. KARAMAT ALI 15 1710040000000023 04126 ZAHANGIR HOSSAIN MOHAMMAD MOLLA 16 1710040000000028 03753 MD.NURUDDIN MD.AMIR HOSSAIN 17 1710040000000029 20472 MD.SHAH EMRAN MD.SHAH ALAM 18 1710040000000030 08603 ANUP KUMAR DAS BIREN CHANDRA DAS 19 1710040000000031 14546 MD. FAISAL SHEIKH. MD. ARMAN SHEIKH. 20 1710040000000035 14773 MD. ARIFUL ISLAM MD. SHAHAB UDDIN 21 1710040000000037 13897 SHAKIL AHMED MD. NURUL ISLAM 22 1710040000000039 06463 MD. PARVES HOSSEN MD. SANA ULLAH 23 1710040000000042 19254 MOHAMMAD TUHIN SHEIKH MOHAMMAD TOMIZADDIN SHEIKH 24 1710040000000043 15792 MD. RABIUL HOSSAIN MD. MAHBUBAR RAHMAN 25 1710040000000047 00997 ANJAN PAUL AMAL PAUL 26 1710040000000048 16489 MAHBUB HASAN MD. AB SHAHID 27 1710040000000049 05703 MD. PARVEZ ALAM MD. SHAH ALAM 28 1710040000000051 10029 MONIRUZZAMAN MD.HABIBUR RAHMAN 29 1710040000000052 18437 SADDAM HOSSAIN MOHAMMAD ALI 30 1710040000000053 07987 MUSTAK AHAMMOD ABU AHAMED 31 1710040000000057 14208 MD. -

List of Voters

List of Voters Life Members 203. Dr. M. A. Waheeduzzaman Associate Professor of History 8. Mr. Mustafa Hasan Eden Girls' College 17/26 Suklal Das Lane, Dhaka Azimpur Estate, Dhaka-1205 9. Mr. M. Hamid Ali 217. Dr. Bhuiyan Nurul Islam Tareq Manzil Professor (Retired) Plot# 52-A, Block# 2 House # 07, Road # 01, Sector # 07, PECH, Karachi, Pakistan Uttara Model Town, Dhaka-1230 14. Mr. A. Z. M. Shamsul Alam 224. Dr. Muhammad Ali Akbar Chairman Urban Harmony Al-Arafa Islami Bank Limited House # 362 (1/D), Road # 27 (Old), Dhanmondi R/A, Dhaka-1209 16. Mr. Anwarul Haque C/O- Md. Nasir 230. Professor Rafiqul Islam House # 69, Road # 8/A House # 44, Road # 05, Sector # 10 Dhanmondi R/A, Dhaka Uttara Model Town, Dhaka-1230 17. Mr. Iqbal Rashid Siddiqi 231. Professor Dr. Manzoor Hasan Macneill & Kilburns Ltd. House # 41, Road # 9/A Motijheel, Dhaka-1000 Suvastu Ruchira Dhanmondi R/A, Dhaka-1209 19. Dr. K. M. Karim PROSHANTI 233. Dr. A.M. Harun-ar-Rashid 177 West Monipur UGC Professor Mirpur, Dhaka-1216 House # 35/A, Road # 4, Flat # 1-B, Dhanmondi R/A, 109. Professor Harun-ur-Rashid Dhaka-1205 House # 26, Road # 10/A, Dhanmondi R/A, Dhaka 234. Dr. Asim Roy University of Tasmania 114. Professor Mahjuza Khanam Hobart 7001, Tasmania, Australia House # 05, Road# 11, Sector # 4, Uttara Model Town, Dhaka-1230 238. Mrs. L. Razzaq C/O-Mr. Razzaq Rahman 126. Mr. Mohammed Abdul Qadir 1 Outer Circular Road 57-Z, Uttar Maniknagar Malibagh, Dhaka-1212 P.O.-Wari, Dhaka-1203 239. -

Chobiwalas of Bangladesh

CHOBI WALAS OF B ANGL ADESH Photographers of Bangladesh © Naibuddin Ahmed © Naibuddin CHOBIWALAS OF BANGLADESH Published by: Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) 31 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119595 T: +65 6874 9700 F: +65 6872 1135 www.ASEF.org Team at Asia-Europe Foundation: Ms Valentina RICCARDI, Ms Anupama SEKHAR, Mr Hatta MOKTAR Researcher: Mr Imran Ahmed Download from ASEF culture360 at http://culture360.ASEF.org/ All rights reserved © Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF), June 2017 Special thanks to the individuals who participated in the research survey and provided relevant information, as well as to the following organisations: Research Assistant: Mohammad Academics: Photographers: Ashraful Huda Tanvir Murad Topu Sayeda Taufika Rahman Elisa Abu Naser Shahidul Alam Hasan Saifuddin Chandan Syeda Kasfia Sharna Main Uddin Md. Hadi Uddin Monirul Alam Volunteers: Sarker Protick Shaqul Asif Design and Layout: Alam Kiron Suvra Kanti Ikram Marina Salmi Rahman Das Rahman Md. Imran Hossain Rony Md Sydur Rahman Tariq Been Habib Photography Clubs: Nafiul Islam Nasim (Dhaka University Photography Society) Shafkat Ahmad (BUET Photographic Society) Yosuf Tushar (Bangladesh Photography Society) The views expressed in this publication do not in any way reflect, in part or in whole, the official opinion or position of the Asia- Europe Foundation (ASEF), ASEF’s partner organisations, or its sponsors. This publication has been produced with financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of ASEF and do not reflect the position of the European Union. The Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) promotes understanding, strengthens relationships and facilitates cooperation among the people, institutions and organisations of Asia and Europe. -

Ashuganj Power Station Company Ltd. (APSCL)

Ashuganj Power Station Company Ltd. (APSCL) List of Valid Candidates for the Post of Assistant Engineer (Electrical) Written Exam Date: 06/05/2016 Venue: ECE Building, BUET, Dhaka Roll Name & Father's Name Present Address 1 2 3 Hafiz Ahmed House: 449, Road: 13, Block: F, Bashundhara Residential AE(E)-0001 S/O. Amin Ahmed Area, Dhaka-1229. Ashik Amin AE(E)-0002 Room # 2010, Titumir Hall, BUET, Dahaka-1000. S/O. Saiful Amin Mohammed Shahadat Hossain C/O. Idris Ahmmed (SD Man), Military Estate Office, Central AE(E)-0003 S/O. Bazlur Rahman Circle, Dhaka Cantonment, Dhaka-1206. Md. Shahjalal Nirjhor Vill. North Nabinagor, P.O: Sherpur Town, P.S: Sherpur AE(E)-0004 S/O. Md. Abdur Rahman Labo Sadar, Dist: Sherpur Md. Nur Nabi C/O. Syed Rafique Ahmed, 38/C-3, Nigar Mention, Hi Level AE(E)-0005 S/O. Shariat Ullah Road, Lalkhan Bazar, Khulshi, Chittagong. Md. Mahamudul Hasan AE(E)-0006 Dr. F. R. Khan Hall, Room # 204, DUET, Gazipur. S/O. Md. Abdul Hie Md. Sazzad Hossain House: 54, Ward: 01, Along Sarder Surujjaman Mohila AE(E)-0007 S/O. Md. Sohrab Ali College Road, P.O+Thana: Dakshinkhan, Dhaka-1230. Md. Muktarul Islam House: 29/1, 2nd Floor, Munshibari Road, Zigatola, AE(E)-0008 S/O. Md. Nurul Islam Dhanmondi, Dhaka. Md. Imtiyaj Sharif C/O. Md. Kantar Alii, Falkamori, Amratoli-3500, Barura, AE(E)-0009 S/O. Md. Kantar Alii Comilla. Md. Shakhaowth Hossain Vill. Kashor, Union: Hobirbari, P.O: Seed Store, Thana: AE(E)-0010 S/O. Md. Shahjhan Bhaluka, Dist: Mymensingh. -

YOUR DHAKA ART SUMMIT “Dhaka Art Summit Has Set the Gold Standard for the Visual Arts in South Asia.” -Bunty Chand, Director of Asia Society, India CONTENTS

YOUR DHAKA ART SUMMIT “Dhaka art summit has set the gold standard for the visual arts in South Asia.” -Bunty Chand, Director of Asia Society, India CONTENTS ABOUT DAS ........................................................................ 6 PROGRAMME ..................................................................... 8 SCHEDULE ........................................................................ 25 VENUE MAP ...................................................................... 54 DHAKA ............................................................................... 56 OUR PARTNERS ................................................................ 60 Front Cover: Louis Kahn, National Parliament Building, Dhaka. Image credit: Randhir Singh 2 3 The Missing One installation view. Photo courtesy of the Dhaka Art Summit and Samdani Art Foundation. Photo credit: Jenni Carter DHAKA ART SUMMIT 2018 “I have never experienced something as art focused, open and inclusive as I just did at Dhaka Art Summit. The calibre of the conversations was a rare happening in our region.¨ -Dayanita Singh, DAS 2016 Participating Artist 5 The Dhaka Art Summit (DAS) is an international, non-commercial research and exhibition platform for art and architecture connected to South Asia. With a core focus on Bangladesh, DAS re-examines how we think about these forms of art in both a regional and an international context. Founded in 2012 by the Samdani Art Foundation, DAS is held every two years in a public- private partnership with the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, with the support of the Ministry of Cultural Affairs and Ministry of Information of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, the National Tourism Board, Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA), and in association with the Bangladesh National Museum. Rejecting the traditional biennale format to create a more generative space for art and exchange, DAS’s interdisciplinary programme concentrates its endeavours towards the advancement and promotion of South Asia’s contemporary and historic creative communities. -

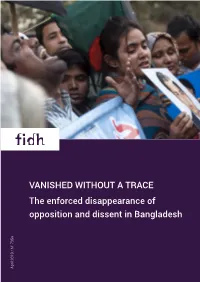

VANISHED WITHOUT a TRACE the Enforced Disappearance of Opposition and Dissent in Bangladesh

VANISHED WITHOUT A TRACE The enforced disappearance of opposition and dissent in Bangladesh April 2019 / N° 735a Cover Photo : Relatives of victims made a human chain in front of the press club in Dhaka demanding an end to enforced disappearance, killing and abduction on International Human Rights Day, December 2014. (Photo by Zakir Hossain Chowdhury/NurPhoto) TABLE OF CONTENTS List of acronyms 6 Executive summary 7 Introduction 8 1. Context 10 1.1 – A conflictual political history 10 1.2 – The 2014 election 11 1.3 – Human rights in Bangladesh today 12 1.4 – Legal framework 15 1.4.1 The Constitution 15 1.4.2 The Penal Code 16 1.4.3 Other domestic laws 17 1.4.4 International legal obligations 17 1.5 – Actors 18 1.5.1 Bangladesh police 19 1.5.2 Intelligence agencies 21 2. Crime of enforced disappearance: Analysis of trends and patterns 22 2.1 – Introduction: periods and trends 22 2.2 – Modus operandi 24 2.2.1 Previous threats, surveillance, and judicial harassment 24 2.2.2 Arbitrary arrest and abduction by agents of the State 28 2.2.3 Disappeared without a trace 29 2.2.4 Conditions of arbitrary detention 30 2.2.5 Fate of the victims of enforced disappearance 32 2.3 – Categories of victims 34 2.3.1 Gender perspective 34 2.3.2 Political opposition activists 35 2.3.3 Critical and dissident voices 37 2.3.4 Persons targeted in the framework of the anti-terrorism policy 38 2.3.5 Other individuals targeted as a result of the culture of impunity 39 2.3.6 Persecution and threats against those who speak out 39 2.4 – Alleged perpetrators 40 2.4.1 Law enforcement agents and intelligence officers 40 2.4.2 Responsibility of the executive branch 42 3. -

''বফজ্ঞবি'' Biological Sciences

গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী ফাাংরদদ যকায বফজ্ঞান ও প্র뷁বি ভন্ত্রণারয় ফাাংরাদদ বিফারয়, ঢাকা। পযাক্সঃ৭১৬১৭৯৮ ওদয়ফঃ www.most.gov.bd ০১ ভাঘ ১৪২৫ নাং- ৩৯.০০.০০০০.০৯.০২.৯০.১৮-০৯ তাবযখঃ ১৪ জাꇁয়াবয ২০১৯ ‘‘বফজ্ঞবি’’ বফলয়: ২০১৮-২০১৯ অথ থ ফছদয বফজ্ঞান ও প্র뷁বি ভন্ত্রণারদয়য "বফজ্ঞান ও প্র뷁বি কভথ বি" খাত দত বফদল অꇁদাদনয জন্য বনফাথবিত বনম্নবরবখত প্রকদেয প্রকে বযিারকগদণয অꇁ嗂দর ১ভ ও ২য় বকবিয বজও জাযী কযা দয়দছ। Biological Sciences Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh SL. Gr. Name of the Principal Address of the Principle Project Title Mobile Recommen No. SL. Investigator & Associate Investigator Number -ded Grant Investigator Amount 1. BS -2 Mr. Md. Masudul Karim Department of Crop Study on production, 01790587543 2.00 Lac Associate Professor Botany processing and preservation of Dr. Md. Abdul Razzak Agriculture University, quality healthy seeds by the Lecturer Mymensingh marginal and small farmers 2. BS -5 Md. Rishad Abdullah Plant Conservation and Collection of Some Critically 01711372859 2.5 Lac Sanjit Chandra Barman Research Foundation Endangered and Endangered prof. Md. Mustafizur House No. 47, Wild Plant Species for Ex Situ Rahman Chattrapur Primary Conservation to Save Them School Road, BAU from Extinction Shesh Moor, PO. Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh 3. BS - Prof. Dr. Khan Md. Department of Animal Fermentation of rice bran 01715226510 3.00 Lac 240 Shaiful Islam Nutrition, Bangladesh using isolated Ruminococcus 01722078264 Ms. Nabilah Jalal Nuha Agricultural University, spp. for desirable chemical Lecturer Mymensingh-2202 changes as animal feed 4. -

Bangladesh: Journalists, the Press and Social Media

Country Policy and Information Note Bangladesh: Journalists, the press and social media Version 2.0 January 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

Three Dreams Or Three Nations?

The Newsletter | No.55 | Autumn/Winter 2010 10 The Study Three dreams or three nations? A recent exhibition1 on South Asian photography entitled ‘Where Three Dreams Cross: 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh’ highlights indigenous or native photographers as a marker of what India was before the two partitions. This is to suggest that there is a history of image-making that stands outside the ambit of European practitioners. The exhibition featured over 400 photographs, a survey of images encompassing early trends and photographers from the 19th century, the social realism of the mid-20th century, the movements of photography from the studio to the streets and, eventually, the playful and dynamic recourse with image-making in the present. Rahaab Allana CULTURAL PRACTITIONERS – whether writers, musicians, Exhibitions are part of a collective enterprise, a space where Images from left Mona Ahmed, the personal life of the eunuch who lives beside painters and even photographers – have endlessly tried to artists and their work often speak for themselves. Given that to right: a graveyard, Pushpmala N.’s engagements with the historical understand the varied ways in which we should and do look India has had a varied encounter with photography over the 1. Photographer archive and the use of iconcity, the use of memory by Vivan beyond borders; and whether those lines of separation monitor last 150 years, any engagement with it in the current scenario from Mumbai, Sundaram through a relay of works on his aunt and grandfather, the inner workings and deeper cultures of engagement in our entails work that assumes to undo, abet and evolve from Unknown Artist, Umrao Sher Gil; these are only some of the links created that dealings with art, and even the curatorial practice engaged with what was done in the past. -

Investment Corporation of Bangladesh Human Resource Management Department List of Valid Candidates for the Post of "Office Sohayok "

Investment Corporation of Bangladesh Human Resource Management Department List of valid candidates for the post of "Office Sohayok" Sl. No Tracking No Roll Name Father's Name 1 1610200000003188 7941 EVA AKTER M ASRAF HOSSEN 2 1610200000003189 1689 MD. ABID HASAN MD. ASRAF ALI 3 1610200000003190 3317 MIZANUR RAHMAN MAZIBUR RAHMAN 4 1610200000003191 4361 MD. KAWSER AHMED LATE MD. TOBARAK ALI 5 1610200000003192 5360 MD. RAFIQUL ISLAM MD. ALA UDDIN 6 1610200000003193 7564 MOKHLESUR NURUL ISLAM 7 1610200000003194 1874 MD. MANIRUZZAMAN MD. ABUL HOSSAIN BAPARI 8 1610200000003195 6010 MD. SAHIDUL HOQUE MD. AZIZUL HOQUE 9 1610200000003196 0571 RAKIBUL ISLAM LATE KHAYEZ UDDIN SARKAR 10 1610200000003197 5492 MD. ABDUR RAHMAN MD. ABDUR ROUF 11 1610200000003198 0803 MD. ASHIF HOSSAIN MD REZAUL HOQUE 12 1610200000003199 2857 MD. AL AMIN ABBAS ALI 13 1610200000003200 2752 MD. RAKIBUL ISLAM MOAZZEM HOSSAIN 14 1610200000003201 5363 ABDUR RAHAMAN MOHAMMAD MOSTAFA KAMAL 15 1610200000003202 5795 RAKIBUL HASAN ABDUL HALIM 16 1610200000003203 0436 MD. FARUK HOSSAIN NURUL ISLAM 17 1610200000003204 6394 ARJUN KUMAR BISWAS BIDHAN KUMAR BISWAS 18 1610200000003205 2111 MD.ARIE OSSAIN MD.GIAS UDDIN 19 1610200000003206 7891 MD. RUHUL AMIN MD. OYAZED ALI 20 1610200000003207 5019 FAHAD AL MAMUN MD FARUK MIAH 21 1610200000003208 1186 MD.MOZAMMEL HAQUE MD.MONSUR ALI 22 1610200000003209 3709 MD. AZIZUL HOQUE MD. NURUL ISLAM 23 1610200000003210 3838 MD. TOHIN MIAH MD. SIRAJ UDDIN 24 1610200000003211 1989 MD.RAJA HASAN MD.SAHJAHAN 25 1610200000003212 1153 RABIN CHANDRA SARKAR GOPAL CHANDRA SARKAR 26 1610200000003213 4954 MD. ZUBAIR MD. MOFIZ UDDIN 27 1610200000003214 4996 MD. MAZED ALI MD. RAFIQUL ISLAM 28 1610200000003215 6104 MD. -

List of Shareholders Having Unclaimed Or Undistributed Or Unsettled Cash Dividend for the Year 2014

Mercantile Bank Limited, Share Department, Board Division, Head Office, Dhaka List of shareholders having unclaimed or undistributed or unsettled cash dividend for the year 2014 Nominee(s), Year of B.O. account / Folio Amount of Sl. # Name of Shareholder Father’s name Mother’s name Permanent & contact address if any dividend Number dividend inTk. 1 Samina Nasreen 23/2, East Nayatola Dhaka Not available 2014 00128 1,806.25 Kapatakka Neer,31,32 Mohammodi Housing 2 Chaitanaya Kumer Dey Late Surandranath Dey Lalita Dey Not available 2014 00187-1301020000236925 13,173.30 Ltd.,Mohammadpur, Dhaka 3 Mohammed Ali 84/2 Central Road, Dhanmondi Dhaka Not available 2014 00322 441.15 4 Md.Humayun Kabir Late Md. Mobaswer Ali Green Delta Ins.Co.Ltd., Nawabpur Road Ranch Dhaka Not available 2014 00342-1301020000172237 1,700.00 5 A. Hasib House # 53, Road # 12/A, Dhanmondi Dhaka Not available 2014 00394 153.85 Road # 7, House # 10, Block # Kha Pc Culture Housing, 6 Rasad Rahman Md. Atiar Rahman Not available 2014 00516 631.55 Mohammedpur Dhaka 1207 7 Rowshan Ara Begum 1011, East Monipur, Mirpur-2 Dhaka 1216 Not available 2014 00728 275.40 16/19, Ground Floor Tajmohal Rd. Block-C Mohammadpur 8 Josephine Rodrigues Not available 2014 00735 934.15 Dhaka 16/19, Ground Floor Tajmohal Rd. Block-C Mohammadpur 9 Martin Rodrigues Not available 2014 00736 1,806.25 Dhaka Texas Resources Ltd., Bta Tower, 10Th Fl 29 Kamal Ataturk, 10 Priyabrata Chowdhury Sadhan Chandra Chowhdury Not available 2014 00818-1201910000805971 476.00 Banani Dhaka 11 Kawsar C/6/18 Bangladesh Bank Colony, Faridabad Dhaka Not available 2014 00861 1,060.80 12 Rokhsana Akhter 222/9, West Dhanmondi, Road # 19, Nmadhubazar Dhaka Not available 2014 00888 567.80 13 Md.