(The Production Of) Who Is a Refugee?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Development Programme

ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 16 - PROGRAMME 2015 PROGRAMME DEVELOPMENT ANNUAL GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT JUNE, 2015 www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk FINAL ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2015-16 GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT http://www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Table of Contents S.No. Sector/Sub Sector Page No. 1 Abstract-I i 2 Abstract-II ii 3 Abstract-III iii 4 Abstract-IV iv-vi 5 Abstract-V vii 6 Abstract-VI viii 7 Abstract-VII ix 8 Abstract-VIII x-xii 9 Agriculture 1-21 10 Auqaf, Hajj 22-25 11 Board of Revenue 26-27 12 Building 28-34 13 Districts ADP 35-35 14 DWSS 36-50 15 E&SE 51-60 16 Energy & Power 61-67 17 Environment 68-69 18 Excise, Taxation & NC 70-71 19 Finance 72-74 20 Food 75-76 21 Forestry 77-86 22 Health 87-106 23 Higher Education 107-118 24 Home 119-128 25 Housing 129-130 26 Industries 131-141 27 Information 142-143 28 Labour 144-145 29 Law & Justice 146-151 30 Local Government 152-159 31 Mines & Minerals 160-162 32 Multi Sectoral Dev. 163-171 33 Population Welfare 172-173 34 Relief and Rehab. 174-177 35 Roads 178-232 36 Social Welfare 233-238 37 Special Initiatives 239-240 38 Sports, Tourism 241-252 39 ST&IT 253-258 40 Transport 259-260 41 Water 261-289 Abstract-I Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Programme-wise summary (Million Rs.) S.# Programme # of Projects Cost Allocation %age 1 ADP 1553 589965 142000 81.2 Counterpart* 54 19097 1953 1.4 Ongoing 873 398162 74361 52.4 New 623 142431 35412 24.9 Devolved ADP 3 30274 30274 21.3 2 Foreign Aid* * 148170 32884 18.8 Grand total 1553 738135 174884 100.0 Sector-wise Throwforward (Million Rs.) S.# Sector Local Cost Exp. -

PAK: Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project

Environmental Impact Assessment: Main Report Project No. 48289-002 April 2017 PAK: Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project Prepared by Peshawar Development Authority (PDA), provincial Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (GoKP) for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). EIA for Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project The Environmental Impact Assessment Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Acronyms 2 | Page EIA for Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS As of 9th April 2017 Currency Unit – Pak Rupees (Pak Rs.) Pak Rs 1.00 = $ 0.0093 US$1.00 = Pak Rs. 107 Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank SPS Safeguard Policy Statement SIA Social Impact Assessment DoF Department of Forests EA Environmental Assessment EARF Environment Assessment Review Framework EAAC Environmental Assessment Advisory Committee EPA Environmental Protection Agency EIA Environment Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan PPDD Punjab Planning and Development Department EA Executing Agency -

Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project Reach 1: Chamkani Mor to Firdous Cinema

Resettlement Plan October 2017 PAK: Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project Reach 1: Chamkani Mor to Firdous Cinema Prepared by the Planning and Development Department, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa for the Asian Development Bank. This is an updated section-wise version for Reach 1 of the draft originally posted in April 2017 available on http://www.adb.org/projects/48289-002/documents. Reach 1 LARP (i) October 2017 This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ii Peshawar Development Authority Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project Land Aquistion and Resettlement Plan For Reach 1 (Chamkani Mor to Firdous Cinema) October 2017 Reach 1 LARP (ii) October 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. 4 1 Introduction............................................................................................................................... -

INSTITUTE of GEOGRAPHY URBAN and REGIONAL PLANNING UNIVERSITY of PESHAWAR-PAKISTAN (November, 2012)

EXPANSION OF BUILT UP AREA AND ITS IMPACT ON URBAN AGRICULTURE: A CASE STUDY OF PESHAWAR-PAKISTAN SAMIULLAH INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR-PAKISTAN (November, 2012) i DEDICATED TO MY PARENTS WHOSE PRAYERS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN A CONSTANT SOURCE OF INSPIRATION AND ENCOURAGEMENT FOR ii Approval Sheet This dissertation titled “Expansion of built up area and its impact on urban agriculture: A case Study of Peshawar-Pakistan” is submitted to the Institute of Geography, Urban and Regional Planning, University of Peshawar in partial fulfillment for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography is hereby approved. External Examiner Internal Examiner iii Acknowledgement I am thankful to Almighty Allah Who enabled me to complete my dissertation. It was not possible without the support of various people. My sincere appreciation goes to my parents, my friends, and my teachers in the Institute of Geography. First of all I would like to pay my thanks to my respected supervisor Prof. Dr. Mohammad Aslam Khan, HEC Professor, who not only guided me at every step but also helped me greatly in writing this thesis. He not only made himself readily available for me but always encouraged and responded timely to my draft more swiftly than my expectations. His verbal and written explanations at all times were exceptionally perceptive, useful and appropriate. I would also like to thank my closest friend Dr. Atta-ur-Rahman, Assistant Professor, Institute of Geography, who helped a lot throughout my thesis from concept generation to final print of the script. In addition my thanks go to Dr. -

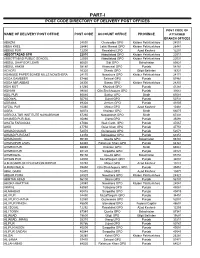

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project Annexures

Environmental Monitoring Report Semestral Report For the period January – June 2019 August 2019 PAK: Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit Corridor Project Annexures (Part II) Prepared by Peshawar Development Authority, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa for the Asian Development Bank. NOTE In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT Of Peshawar Sustainable Bus Rapid Transit System, (PSBRT) Building Package Lot – I (Hayatabad Depot) 3 May, 2019 ANHUI Prepared By: Green Crescent Environmental Consultants Pvt. Ltd. Reference Number: GCEC-PK-160/2019 Contact Details of Client Contact Person Mr. Fahad Ikram Designation HSE Manager Contact Number +92-331-9780130 Fax - Email ID [email protected] Address House # 52, Sector G-2, Phase-2, Hayatabad, Peshawar. Contact Details of GCEC-Pakistan Country Manager: Mr. Rashid Maqbool. Telephone: +92-42-35761300 Fax: +92-42-35761301 Email: [email protected] Address 112 C/E-1, Hali Road, Gulberg III, Lahore Approved By: Country Manager GCEC-Pakistan Environmental Monitoring Report Reference Number: GCEC-PK-160/2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 SECTION 1: COMPANY INTRODUCTION ...................................... 1-1 1.1 STUDY OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................................. -

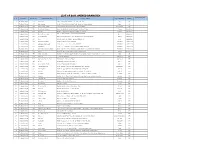

LIST of BOK OPENED BRANCHES Controlling Branch Sr

LIST OF BOK OPENED BRANCHES Controlling Branch Sr. No. Bank Name Branch Code Branch/Booth Name Complete Address City/Town/Village Province (In case of Sub-branch and Permanent Booth) 1 The Bankof Khyber 0064 Kotli (AJK) Commercial Property, Khasra No.579, Bank Road, Kotli Kotli AJK 2 The Bankof Khyber 0035 Mirpur Branch Plot No.3, Sector B/3, Allama Iqbal Road, Mirpur, Azad Jammu Kashmir Mirpur AJK 3 The Bankof Khyber 0027 Muzaffar Abad (AJ&K) Secretariat Road, Muzaffarabad, Azad Jammu & Kashmir Muzaffarabad AJK 4 The Bank of Khyber 0120 Abdali Bazar Chaman-I Khasra No. 451, Old Mahal Abdali Bazaar, Trunch Road, Chaman. Chaman Baluchistan 5 The Bankof Khyber 0095 Gawadar Main Bazar, Airport Road, Adjacent to Sahil Hotel, Gawadar. Gawadar Baluchistan Shahra-e-Iqbal (Khasra no.205), Qandhari Bazar, Quetta. 6 The Bankof Khyber 0054 Quetta, Shahra-e-Iqbal Quetta Baluchistan 7 The Bankof Khyber 0148 Sirki Road Quetta Khasra No. 1807/16, Kaasi Building, Groud & 1st Floor, Sirki Road, Quetta Quetta Baluchistan 8 The Bank of Khyber 0177 Zhob Shop No. C84-85 Main Bazar, Thana Road Quetta Zhob Zhob Baluchistan 9 The Bankof Khyber 0022 Blue area, Islamabad 38-Zahoor Plaza, Blue Area, Islamabad. Islamabad Federal Capital 10 The Bankof Khyber 0055 Islamabad, PWD Society Plot No.786-G, Block-C, PWD Society, Islamabad Islamabad Federal Capital 11 The Bank of Khyber 0133 Islamabad F-10 Plot No. 08, F-10 Markaz, Al-Maroof Hospital Building, Islamabad. Islamabad Federal Capital 12 The Bankof Khyber 0180 Bhara Kahu Branch, Islamabad Malak Shafait Plaza, manuza mahal kot, hathial Main Maree road Bhara Kahu Islamabad Islamabad Federal Capital 13 The Bankof Khyber 0146 Tarnol kharsa No. -

DFG Part-L Development Settled

DEMANDS FOR GRANTS DEVELOPMENTAL EXPENDITURE FOR 2020–21 VOL-III (PART-L) GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA FINANCE DEPARTMENT REFERENCE TO PAGES DFG PART- L GRANT # GRANT NAME PAGE # - SUMMARY 01 – 23 50 DEVELOPMENT 24 – 177 51 RURAL AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT 178 – 228 52 PUBLIC HEALTH ENGINEERING 229 – 246 53 EDUCATION AND TRAINING 247 – 291 54 HEALTH SERVICES 292 – 337 55 CONSTRUCTION OF IRRIGATION 338 – 385 CONSTRUCTION OF ROADS, 56 386 – 456 HIGHWAYS AND BRIDGES 57 SPECIAL PROGRAMME 457 – 475 58 DISTRICT PROGRAMME 476 59 FOREIGN AIDED PROJECTS 477 – 519 ( i ) GENERAL ABSTRACT OF DISBURSEMENT (SETTLED) BUDGET REVISED BUDGET DEMAND MAJOR HEADS ESTIMATES ESTIMATES ESTIMATES NO. -

Tanya* (Afghanistan)

TANYA* (AFGHANISTAN) “...I still have one foot in Afghanistan and the other foot in Canada.” Life before Canada C A m H 64 u 66 68 70 72 Mur 74 H ° D ° ° ° a-ye ° gho ° ar y b INA ya UZBEKISTAN r INA a AFGHANISTAN D Qurghonteppa TAJIKISTAN Birthplace and Family Kerki (Kurgan-Tyube) Mary Kiroya iz M rm Dusti Khorugh u e BADAKHSHAN r T g a Keleft Rostaq FayzFayzabad Abad I was born in Kabul, Afghanistan, on January 1, b ir Qala-I-Panjeh Andkhvoy Jeyretan am JAWZJAN P Mazar-e-Sharif KUNDUZ TaluqanTaloqan Jorm 1989. Prior to coming to Canada, I lived in TURKMENISTAN Shiberghan Kunduz h Eshkashem s Dowlatabad BALKH Kholm Khanabad TAKHAR u Peshawar, Pakistan. I am a Muslim. My family speaks T K e d Baghlan Farkhar 36 z ° h Shulgarah e u 36 Farsi. I speak Farsi, Urdu, Pashtu, and English. I n Sari Pul Aybak Dowshi ° d y Maymana g BAGHLAN h SAMANGAN n Gilgit s have two brothers (Atash and Babur), one sister u FARYAB Tokzar i G ISLAMIC Qeysar PANJSHER H AFGHANISTAN r Gushgy a SARI PUL Bazarak n (Azin), and my mother (Afshan) and father (Asa). I u Jammu BADGHIS Mahmud-e- NURISTAN K Towraghondi Raqi ns had a very good relationship with all my family. Taybad oru KUNAR Mo Chaharikar N P and Qala-e-Naw rghab BAMYAN KAPISA A PARWAN M Asad Abad Mehtarlam Dowlat Bamyan H HiratHerat Chaghcharan Yar G Kashmir H Karokh A ar Owbeh Maydan Kabul ir L Jalalabad ud Shahr KABUL My father died before we moved to Pakistan. -

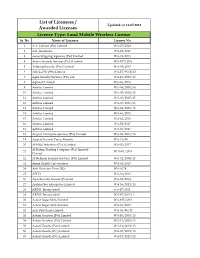

Total List of RBS Licensees Updated on 13-07-2018.Xlsx

List of Licensees / Updated on 13-07-2018 Awarded Licenses License Type: Land Mobile Wireless License Sr. No Name of Licensee License No. 1 A.A. Joyland (Pvt) Limited W.6-27/2014 2 A.R. Associates W.6-29/2017 3 Aaras Shipping Agencies (Pvt) Limited W.6-49/2015 4 Access Security Services (Pvt.) Limited W.6-107/2016 5 Achtung Security (Pvt.) Limited W.6-69/2017 6 AES Lal Pir (Pvt) Limited W.6-17/96/B/15 7 Agha Security Services (Pvt) Ltd W.6-10/2005/15 8 Agritech Limited W.6-26/2015 9 Airblue Limited W.6-04/2005/18 10 Airblue Limited W.6-05/2005/15 11 Airblue Limited W.6-06/2005/15 12 Airblue Limited W.6-07/2005/15 13 Airblue Limited W.6-08/2005/15 14 Airblue Limited W.6-46/2015 15 Airblue Limited W.6-62/2016 16 Airblue Limited W.6-53/2017 17 Airblue Limited W.6-50/2017 18 Airport Limousine Services (Pvt) Limited W.6-25/2013/18 19 Airport Security Force, Karachi W.6-31/80 20 Al-Hilal Industries (Pvt.) Limited W.6-02/2017 Al-Rahim Trading Company (Pvt) Limited- 21 W.15-01/2014 Coastal 22 Al-Rehman Security Services (Pvt) Limited W.6-02/2004/15 23 Aman Health Care Services W.6-44/2017 24 Anti Narcotics Force HQs W.6-9/74 25 APCO W.6-66/2016 26 Aqsa Security Guards (Pvt) Ltd W.6-25/2014 27 Arabian Sea Enterprises Limited W.6-36/2013/18 28 ARINC Incorporated w.6-47/2015 29 ARINC Incorporated W.6-47/2015/1 30 Ashraf Sugar Mills Limited W.6-105/2016 31 Ashraf Sugar Mills Limited W.6-66/2017 32 Asia Petroleum Limited W.6-65/96/15 33 Askari Aviation (Pvt) Limited W.6-10/2003/15 34 Askari Aviation (Pvt) Limited W.6-11/2003/15 35 Askari Guards (Pvt) -

ADP 2021-22 Planning and Development Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Page 1 of 446 NEW PROGRAMME

ONGOING PROGRAMME SECTOR : Agriculture SUB-SECTOR : Agriculture Extension 1.KP (Rs. In Million) Allocation for 2021-22 Code, Name of the Scheme, Cost TF ADP (Status) with forum and Exp. upto Beyond S.#. Local June 21 2021-22 date of last approval Local Foreign Foreign Cap. Rev. Total 1 170071 - Improvement of Govt Seed 288.052 0.000 230.220 23.615 34.217 57.832 0.000 0.000 Production Units in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. (A) /PDWP /30-11-2017 2 180406 - Strengthening & Improvement of 60.000 0.000 41.457 8.306 10.237 18.543 0.000 0.000 Existing Govt Fruit Nursery Farms (A) /DDWP /01-01-2019 3 180407 - Provision of Offices for newly 172.866 0.000 80.000 25.000 5.296 30.296 0.000 62.570 created Directorates and repair of ATI building damaged through terrorist attack. (A) /PDWP /28-05-2021 4 190097 - Wheat Productivity Enhancement 929.299 0.000 378.000 0.000 108.000 108.000 0.000 443.299 Project in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Provincial Share-PM's Agriculture Emergency Program). (A) /ECNEC /29-08-2019 5 190099 - Productivity Enhancement of 173.270 0.000 98.000 0.000 36.000 36.000 0.000 39.270 Rice in the Potential Areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Provincial Share-PM's Agriculture Emergency Program). (A) /ECNEC /29-08-2019 6 190100 - National Oil Seed Crops 305.228 0.000 113.000 0.000 52.075 52.075 0.000 140.153 Enhancement Programme in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Provincial Share-PM's Agriculture Emergency Program). -

KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA GOVERNANCE PROJECT Six-Month Workplan April – September 2017

KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA GOVERNANCE PROJECT Six-Month Workplan April – September 2017 CONTRACT NO. AID-391-C-15-00006 April 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. TERRITORIAL MARKETING: REGION DE L’ORIENTAL TRIP REPORT 1 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Governance Project Six-Month Workplan April – September 2017 Program Name: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Governance Project Contract No.: AID-391-C-15-00006 Office: USAID ǀ Pakistan Date: April 30, 2017 Author: DAI The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. SEVENTH SIX-MONTH WORKPLAN: APRIL – SEPTEMBER 2017 i TABLE OF CONTEN TS TABLE OF CONTEN TS ..........................................................................................................................II ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................................................III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 II. OVERVIEW: PRIOR WORKPLAN PERIOD ......................................................................................... 3 III. ACTIVITIES PLANNED DURING NEXT SIX MONTHS........................................................................