Special Case of the Three-Dimensional Pythagorean Gear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Favourite Problem No.1 Solution

My Favourite Problem No.1 Solution First write on the measurements given. The shape can be split into different sections as shown: d 8 e c b a 10 From Pythagoras’ Theorem we can see that BC2 = AC2 + AB2 100 = 64 + AB2 AB = 6 Area a + b + c = Area of Semi-circle on BC (radius 5) = Area c + d = Area of Semi-circle on AC (radius 4) = Area b + e = Area of Semi-circle on AB (radius 3) = Shaded area = Sum of semi-circles on AC and AB – Semi-circle on BC + Triangle Area d + e = d + c + b + e - (a + b + c ) + a = + - + = = 24 (i.e. shaded area is equal to the area of the triangle) The final solution required is one third of this area = 8 Surprisingly you do not need to calculate the areas of the semi-circles as we can extend the use of Pythagoras’ Theorem for other shapes on the three sides of a right-angled triangle. Triangle ABC is a right-angled triangle, so the sum of the areas of the two smaller semi-circles is equal to the area of the larger semi-circle on the hypotenuse BC. Consider a right- angled triangle of sides a, b and c. Then from Pythagoras’ Theorem we have that the square on the hypotenuse is equal to c a the sum of the squares on the other two sides. b Now if you multiply both sides by , this gives c which rearranges to . a b This can be interpreted as the area of the semi-circle on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the areas of the semi-circles on the other two sides. -

Right Triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem Related?

Activity Assess 9-6 EXPLORE & REASON Right Triangles and Consider △ ABC with altitude CD‾ as shown. the Pythagorean B Theorem D PearsonRealize.com A 45 C 5√2 I CAN… prove the Pythagorean Theorem using A. What is the area of △ ABC? Of △ACD? Explain your answers. similarity and establish the relationships in special right B. Find the lengths of AD‾ and AB‾ . triangles. C. Look for Relationships Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ ABC VOCABULARY by the length of one of its sides. Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ACD by the length of one of its sides. Make a conjecture that explains • Pythagorean triple the results. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How are similarity in right triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem related? Remember that the Pythagorean Theorem and its converse describe how the side lengths of right triangles are related. THEOREM 9-8 Pythagorean Theorem If a triangle is a right triangle, If... △ABC is a right triangle. then the sum of the squares of the B lengths of the legs is equal to the square of the length of the hypotenuse. c a A C b 2 2 2 PROOF: SEE EXAMPLE 1. Then... a + b = c THEOREM 9-9 Converse of the Pythagorean Theorem 2 2 2 If the sum of the squares of the If... a + b = c lengths of two sides of a triangle is B equal to the square of the length of the third side, then the triangle is a right triangle. c a A C b PROOF: SEE EXERCISE 17. Then... △ABC is a right triangle. -

Y-Axis, Respectively

A.2 GEOMETRY REVIEW Pythagorean Theorem (A.2 p. 582) Hypotenuse c The Pythagorean Theorem is a statement about Leg right triangles. A right triangle is one that b contains a right angle, that is, an angle of 90º. 90º The side of the triangle opposite the 90º angle is called the hypotenuse; the remaining two Leg a sides are called legs. In the figure on the left, we have used c to represent the length of the hypotenuse and a and b to represent the lengths of the legs. Pythagorean Theorem: In a right triangle, the square of the length of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the legs. Conversely, if the square of the length of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the legs of a triangle, then the triangle is a right triangle, where the 90º angle is opposite the longest side. c2 = a2 + b2 From this we can derive the following equations: c = (a2 + b2 ) a = (c2 − b2 ) b = (c2 − a2 ) Example 1 In a right triangle, one leg is of length 4 and the other is of length 3. What is the length of the hypotenuse? c = hypotenuse a = 4 b = 3 Using the Pythagorean theorem, we know c2 = a2 + b2 c2 = 42 + 32 = 16 + 9 = 25 c = 25 = 5 Now do Problem 9 on p.585 Example 2 Verifying That a Triangle is a Right Triangle Show that a triangle whose sides are of lengths 5, 12, and 13 is a right triangle. -

Pythagoras' Theorem Information Sheet Finding the Length of the Hypotenuse

Pythagoras’ Theorem In this activity you will use Pythagoras’ Theorem to solve real-life problems. Information sheet There is a formula relating the three sides of a right-angled triangle. It can be used to mark out right angles on sports pitches and buildings. If the length of the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is c and the lengths of the other sides are a and b: 2 2 2 c = a + b c 2 2 2 a and a = c – b 2 2 2 and b = c – a b To find the hypotenuse, add the squares of the other sides, then take the square root. To find a shorter side, subtract the squares of the other sides, then take the square root. Think about … How do you decide which sides to call a, b and c? How do you decide whether to add or subtract? Finding the length of the hypotenuse: example Find c. 12.4 cm 6.3 cm c How to do it …. Using Pythagoras gives c2 = 6.32 + 12.42 c 2 = 39.69 + 153.76 = 193.45 c = 193.45 = 13.9086… c = 13.9 cm (to 1 dp) Nuffield Free-Standing Mathematics Activity ‘Pythagoras Theorem’ Student sheets Copiable page 1 of 4 © Nuffield Foundation 2012 ● downloaded from www.fsmq.org Rollercoaster example C The sketch shows part of a rollercoaster ride between two points, A and B at the same horizontal level. drop The highest point C is 20 metres above AB, ramp 30 m the length of the ramp is 55 metres, and 55 m 20 m the length of the drop is 30 metres. -

Trigonometry Review

Trigonometry Review Math Tutorial Lab Special Topic∗ Right Triangle Trigonometry We will first define our trig functions using a right triangle. Remember that the angles of a right triangle are no larger than 90◦, so we will only consider trig functions restricted to these angles at first. Our trig functions will relate the sides of the right triangle in various ways. With this in mind, we define these functions as follows. For the angle θ in the right triangle shown in Figure 1, we have: b a b c c a sin θ = ; cos θ = ; tan θ = ; csc θ = ; sec θ = ; cot θ = : c c a b a b θ θ c hypotenuse a adjacent leg b opposite leg Figure 1 Figure 2 We often use the acronym SOHCAHTOA to remember the formulas for sine, cosine, and tangent. SOHCAH- TOA stands for Sine Opposite Hypotenuse, Cosine Adjacent Hypotenuse, Tangent Opposite Adjacent. The terms \opposite," \adjacent," and \hypotenuse" refer to the opposite and adjacent legs and the hypotenuse relative to our angle θ. Remember that the hypotenuse is always the side across from the right angle, and is always the longest side in a right triangle. The acronym SOHCAHTOA tells you the ratio of the sides of the right triangle that give these common trig functions. Figure 2 illustrates this. If we write our trig functions in these terms, we'd have: Opposite Leg Adjacent Leg Opposite Leg sin θ = cos θ = tan θ = Hypotenuse Hypotenuse Adjacent Leg Hypotenuse Hypotenuse Adjacent Leg csc θ = sec θ = cot θ = Opposite Leg Adjacent Leg Opposite Leg We'll now use these formulas to compute the trigonometric functions for some angles in a right triangle. -

Lecture 21: Right Triangles

Lecture 21: Right Triangles 21.1 Right Triangles Definition We call a triangle 4ABC in a protractor geometry a right triangle if one of ∠A, ∠B, or ∠C is a right angle. We call a side opposite a right angle in a right triangle a hypotenuse. Definition In a protractor geometry, we call AB the longest side of 4ABC if AB > AC and AB > BC, and we call AB a longest side if AB ≥ AC and AB ≥ BC. Theorem If, in a neutral geometry, 4ABC is a right triangle with ∠C a right angle, then ∠A and ∠B are acute and AB is the longest side of 4ABC. Proof Let D be a point such that D − C − B. Then ∠DCA is a right angle, exterior to 4ABC with remote interior angles ∠A and ∠B. Hence ∠DCA > ∠A and ∠DCA > ∠B. Since ∠DCA ' ∠ACB, it follows that ∠C > ∠A and ∠C > ∠B. Hence ∠A and ∠B are both acute. Moreover, it also follows that AB > AC and AB > BC. Note that the previous result says that a right triangle has only one hypotenuse and that the hypotenuse is the longest side of a right triangle. Definition Given a right triangle 4ABC with right angle at C in a neutral geometry, we call AC and BC the legs of 4ABC. Theorem If P and Q are points and ` is a line in a neutral geometry with Q ∈ ` and ←→ P/∈ L, then PQ ⊥ ` if and only if PQ ≤ PR for all R ∈ `. ←→ Proof Suppose PQ ⊥ ` and R ∈ `. If R = Q, then PQ = PR. -

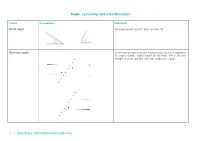

Angle, Symmetry and Transformation 1 | Numeracy and Mathematics Glossary

Angle, symmetry and transformation T e rms Illustrations Definition Acute angle An angle greater than 0° and less than 90°. Alternate angles Where two straight lines are cut by a third, as in the diagrams, the angles d and e (also c and f) are alternate. Where the two straight lines are parallel, alternate angles are equal. 1 | Numeracy and mathematics glossary Angle, symmetry and transformation Angle An angle measures the amount of ‘turning’ between two straight lines that meet at a vertex (point). Angles are classified by their size e.g. can be obtuse, acute, right angle etc. They are measured in degrees (°) using a protractor. Axis A fixed, reference line from which locations, distances or angles are taken. Usually grids have an x axis and y axis. Bearings A bearing is used to represent the direction of one point relative to another point. It is the number of degrees in the angle measured in a clockwise direction from the north line. In this example, the bearing of NBA is 205°. Bearings are commonly used in ship navigation. 2 | Numeracy and mathematics glossary Angle, symmetry and transformation Circumference The distance around a circle (or other curved shape). Compass (in An instrument containing a magnetised pointer which shows directions) the direction of magnetic north and bearings from it. Used to help with finding location and directions. Compass points Used to help with finding location and directions. North, South, East, West, (N, S, E, W), North East (NE), South West (SW), North West (NW), South East (SE) as well as: • NNE (north-north-east), • ENE (east-north-east), • ESE (east-south-east), • SSE (south-south-east), • SSW (south-south-west), • WSW (west-south-west), • WNW (west-north-west), • NNW (north-north-west) 3 | Numeracy and mathematics glossary Angle, symmetry and transformation Complementary Two angles which add together to 90°. -

Hypotenuse Please by Dr

Curriculum Burst 68: Hypotenuse Please By Dr. James Tanton, MAA Mathematician in Residence A right triangle has perimeter 32 and area 20 . What is the length of its hypotenuse? QUICK STATS: MAA AMC GRADE LEVEL This question is appropriate for the junior high-school grade levels. MATHEMATICAL TOPICS The Pythagorean Theorem; Systems of Equations COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS 8.G.7 Apply the Pythagorean Theorem to determine unknown side lengths in right triangles in real-world and mathematical problems in two and three dimensions. A.REI.7 Solve a simple system consisting of a linear equation and a quadratic equation in two variables algebraically and graphically. MATHEMATICAL PRACTICE STANDARDS MP1 Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. MP2 Reason abstractly and quantitatively. MP3 Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. MP7 Look for and make use of structure. PROBLEM SOLVING STRATEGY ESSAY 1: ENGAGE IN SUCCESSFUL FLAILING SOURCE: This is question # 18 from the 2008 MAA AMC 10A Competition. 1 THE PROBLEM-SOLVING PROCESS: As always, one starts the problem-solving process with … Aha! pq+=32 − r and p22++ q2 pq =+ r 2 80 . We STEP 1: Read the question, have an have: emotional reaction to it, take a deep breath, and then reread the question. 2 (32 −=+rr) 2 80 . This question doesn’t feel too scary to me. If I draw and label a right triangle as follows: Alright. Expanding gives: 322− 64rr +=+ 22 r 80 1024−= 64r 80 64r = 944 So 944 450++ 22 225 11 r = = = we are told: 64 32 16 236 118 59 ++= = = = pqr32 16 8 4 1 pq = 20 2 We’re done! and we are being asked to find r . -

Trig Ratios in Right Triangles

Advanced Mathematical Concepts Chapter 5 Lesson 5-2 Example 1 Find the values of the sine, cosine, and tangent for C. First, find the length of AB . (AB)2 + (AC)2 = (BC)2 Pythagorean Theorem (AB)2 + 302 = 452 Substitute 30 for AC and 45 for BC. (AB)2 = 1125 AB = 1125 or 15 5 Take the square root of each side. Disregard the negative root. Then write each trigonometric ratio. side opposite side adjacent side opposite sin C = cos C = tan C = hypotenuse hypotenuse side adjacent 15 5 5 30 2 15 5 5 sin C = or cos C = or tan C = or 45 3 45 3 30 2 Trigonometric ratios are often simplified, but never written as mixed numbers. Example 2 PHYSICS When an object rests on a frictionless surface, the forces acting upon it are gravity and the normal force. The normal force FN is always perpendicular to the surface upon which the object sits, and is defined by FN = mg cos , where m is the mass of the object, g is acceleration due to gravity, and is the angle of inclination of the surface. Suppose a 30 kilogram object is resting on a surface that is at a 25° incline. What is the normal force, in Newtons, acting upon the object given that acceleration due to gravity is 9.8 m/s2? FN = mg cos Definition of normal force FN = (30)(9.8) cos 25° Substitute 30 for m, 9.8 for g, and 25° for . FN (30)(9.8)(0.906307787) Use a calculator to find the cosine ratio. -

Schaum''s Outline of Geometry

Geometry This page intentionally left blank Geometry includes plane, analytic, and transformational geometries Fourth Edition Barnett Rich, PhD Former Chairman, Department of Mathematics Brooklyn Technical High School, New York City Christopher Thomas, PhD Assistant Professor, Department of Mathematics Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts, North Adams, MA Schaum’s Outline Series New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2009, 2000, 1989 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-07-154413-9 MHID: 0-07-154413-5 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-154412-2, MHID: 0-07-154412-7. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative please visit the Contact Us page at www.mhprofessional.com. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

Right Triangle

27 Lesson 2: The Pythagorean Theorem and Similar Triangles A Brief Review of the Pythagorean Theorem. Recall that an angle which measures 90º is called a right angle. If one of the angles of a triangle is a right angle, then we call the triangle a right triangle. In a right triangle, the two sides of the triangle that form the right angle are called the legs of the right triangle, and the side of the triangle which is opposite to the right angle is called the hypotenuse of the triangle. leg hypotenuse right angle leg Right Triangle We are now ready to state: The Pythagorean Theorem. In a triangle which has sides of lengths a, b and c, if the sides of length a and b form a right angle, then side lengths satisfy the following equation: a2 + b2 = c2. b c a In words, the Pythagorean Theorem says “The square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides.” 28 There are many different explanations of why the Pythagorean Theorem is true. These explanations are called proofs of the Pythagorean Theorem and we will give them more attention later in this lesson.1 Here we focus on applications of the Pythagorean Theorem. We now present three sample applications of the Pythagorean Theorem. In each application, we will use the Pythagorean Theorem to find the unknown side length. When performing these calculations, we will pay careful attention to the units in which the given data is presented, and we will obey the two Calculation Rules stated in Lesson 1. -

Chapter 4 Euclidean Geometry

Chapter 4 Euclidean Geometry Based on previous 15 axioms, The parallel postulate for Euclidean geometry is added in this chapter. 4.1 Euclidean Parallelism, Existence of Rectangles De¯nition 4.1 Two distinct lines ` and m are said to be parallel ( and we write `km) i® they lie in the same plane and do not meet. Terminologies: 1. Transversal: a line intersecting two other lines. 2. Alternate interior angles 3. Corresponding angles 4. Interior angles on the same side of transversal 56 Yi Wang Chapter 4. Euclidean Geometry 57 Theorem 4.2 (Parallelism in absolute geometry) If two lines in the same plane are cut by a transversal to that a pair of alternate interior angles are congruent, the lines are parallel. Remark: Although this theorem involves parallel lines, it does not use the parallel postulate and is valid in absolute geometry. Proof: Assume to the contrary that the two lines meet, then use Exterior Angle Inequality to draw a contradiction. 2 The converse of above theorem is the Euclidean Parallel Postulate. Euclid's Fifth Postulate of Parallels If two lines in the same plane are cut by a transversal so that the sum of the measures of a pair of interior angles on the same side of the transversal is less than 180, the lines will meet on that side of the transversal. In e®ect, this says If m\1 + m\2 6= 180; then ` is not parallel to m Yi Wang Chapter 4. Euclidean Geometry 58 It's contrapositive is If `km; then m\1 + m\2 = 180( or m\2 = m\3): Three possible notions of parallelism Consider in a single ¯xed plane a line ` and a point P not on it.