Ruthenium Compounds As Anticancer Agents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Osmium(II) Polypyridyl Complexes Wesley R. Browne a Thesis Pres

Probing ground and excited state properties of Ruthenium(II) and Osmium(II) polypyridyl complexes Wesley R. Browne A Thesis presented to Dublin City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2002 Probing ground and excited state properties of Ruthenium(II) and Osmium(II) polypyridyl complexes Isotope, pH, solvent and temperature effects. by Wesley R. Browne, BSc.(Hons), AMRSC A Thesis presented to Dublin City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Supervisor: Professor Johannes G. Vos School of Chemical Sciences Dublin City University August 2002 Dedicated to Matthew & to the memory of Ross and Mick “Caste a cold eye on life, on death. Horseman pass by” Epitaph fo r William Butler Yeats REFERENCE I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy by research and thesis, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited within the text of my work. I D. No. 95478965 Date:_______ ( ( / Û / iv Abstract The area of ruthenium(H) and osmium(H) polypyridyl chemistry has been the subject of intense investigation over the last half century. In chapter 1, topics relevant to the studies presented in this thesis are introduced. These areas include the basic principles behind the ground and excited state properties of Ru(II) and Os(II) polypyridyl complexes, complexes incorporating the 1,2,4-triazole moiety and the application of deuteriation to inorganic photophysics. Chapter 2 details experimental and basic synthetic procedures employed in the studies presented in later chapters. -

Historical Development of the Periodic Classification of the Chemical Elements

THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PERIODIC CLASSIFICATION OF THE CHEMICAL ELEMENTS by RONALD LEE FFISTER B. S., Kansas State University, 1962 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree FASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Physical Science KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 196A Approved by: Major PrafeLoor ii |c/ TABLE OF CONTENTS t<y THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITION 0? TEH-IS USED 1 The Problem 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Importance of the Study 1 Definition of Terms Used 2 Atomic Number 2 Atomic Weight 2 Element 2 Periodic Classification 2 Periodic Lav • • 3 BRIEF RtiVJiM OF THE LITERATURE 3 Books .3 Other References. .A BACKGROUND HISTORY A Purpose A Early Attempts at Classification A Early "Elements" A Attempts by Aristotle 6 Other Attempts 7 DOBEREBIER'S TRIADS AND SUBSEQUENT INVESTIGATIONS. 8 The Triad Theory of Dobereiner 10 Investigations by Others. ... .10 Dumas 10 Pettehkofer 10 Odling 11 iii TEE TELLURIC EELIX OF DE CHANCOURTOIS H Development of the Telluric Helix 11 Acceptance of the Helix 12 NEWLANDS' LAW OF THE OCTAVES 12 Newlands' Chemical Background 12 The Law of the Octaves. .........' 13 Acceptance and Significance of Newlands' Work 15 THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF LOTHAR MEYER ' 16 Chemical Background of Meyer 16 Lothar Meyer's Arrangement of the Elements. 17 THE WORK OF MENDELEEV AND ITS CONSEQUENCES 19 Mendeleev's Scientific Background .19 Development of the Periodic Law . .19 Significance of Mendeleev's Table 21 Atomic Weight Corrections. 21 Prediction of Hew Elements . .22 Influence -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

The Periodic Table of Elements

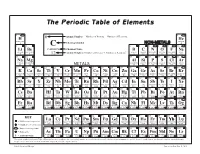

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

Iron-Catalyzed Reactions and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopic Studies

Arnar Guðmundsson Iron-Catalyzed Reactions and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopic Studies of Palladium- and Iron-Catalyzed Reactions and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopic Studies of Palladium- and Ruthenium-Catalyzed Reactions and Ruthenium-Catalyzed Studies of Palladium- Absorption Spectroscopic Reactions and X-Ray Iron-Catalyzed Ruthenium-Catalyzed Reactions Arnar Guðmundsson Arnar Guðmundsson was born in Reykjavík, Iceland. After finishing his bachelor studies in biochemistry at the University of Iceland, he moved to Sweden to pursue his masters and doctoral studies under the guidance of Prof. Jan-Erling Bäckvall. ISBN 978-91-7911-264-6 Department of Organic Chemistry Doctoral Thesis in Organic Chemistry at Stockholm University, Sweden 2020 Iron-Catalyzed Reactions and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopic Studies of Palladium- and Ruthenium-Catalyzed Reactions Arnar Guðmundsson Academic dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Organic Chemistry at Stockholm University to be publicly defended on Friday 22 January 2021 at 10.00 in Magnélisalen, Kemiska övningslaboratoriet, Svante Arrhenius väg 16 B. Abstract The focus of this thesis is twofold: The first is on the application of iron catalysis for organic transformations. The second is on the use of in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to investigate the mechanisms of a heterogeneous palladium- catalyzed reaction and a homogeneous ruthenium-catalyzed reaction. In chapters two, three and four, the use of iron catalyst VI, or its analog X, is described for (I) the DKR of sec-alcohols to produce enantiomerically pure acetates; (II) the cycloisomerization of α-allenols and α-allenic sulfonamides, giving 2,3-dihydrofuran or 2,3-dihydropyrrole products, respectively, with excellent diastereoselectivity; and (III) the aerobic biomimetic oxidation of primary- and secondary alcohols to their respective aldehydes or ketones. -

The Separation and Determination of Osmium and Ruthenium

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1969 The epS aration and Determination of Osmium and Ruthenium. Harry Edward Moseley Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Moseley, Harry Edward, "The eS paration and Determination of Osmium and Ruthenium." (1969). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1559. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1559 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ThU dissertation has been 69-17,123 microfilmsd exactly as received MOSELEY, Harry Edward, 1929- THE SEPARATION AND DETERMINATION OF OSMIUM AND RUTHENIUM. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, PhJ>., 1969 Chemistry, analytical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE SEPARATION AND DETERMINATION OF OSMIUM AND RUTHENIUM A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Chemistry Harry Edward Moseley B.S., Lpuisiana State University, 1951 M.S., Louisiana State University, 1952 J anuary, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks are due to Dr. Eugene W. Berg under whose direction this work was performed, to Dr. A. D. Shendrikar for his help in the tracer studies, and to Mr. J. H. R. Streiffer for his help in writing the com puter program. -

Studies of Dissolution Solutions of Ruthenium Metal, Oxide and Mixed Compounds in Nitric Acid F. Mousset1, C. Eysseric1, F. Bedi

P2-38 Studies of dissolution solutions of ruthenium metal, oxide and mixed compounds in nitric acid F. Mousset 1, C. Eysseric1, F. Bedioui2 1CEA DEN/SE2A, Valrhô-Marcoule, BP 17171, 30207 Bagnols-sur-Cèze Cedex, France 2Laboratoire de Pharmacologie Chimique et Génétique, FRE CNRS-ENSCP n°2463, École Nationale Supérieure de Chimie de Paris, 11 rue Pierre et Marie Curie, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France Abstract – Ruthenium is one of the fission products generated by irradiated nuclear fuel. It is present throughout all the steps of nuclear fuel reprocessing —particularly during extraction—and requires special attention due to its complex chemistry and high bg activity. An innovative electrovolatilization process is now being developed to take advantage of the volatility of RuO4 in order to eliminate it at the head end of the PUREX process and thus reduce the number of extraction cycles. Although the process operates successfully with synthetic nitrato-RuNO3+ solutions, difficulties have been encountered in extrapolating it to real-like dissolution solutions. In order to better approximate the chemical forms of ruthenium found in fuel dissolution solutions, kinetic and speciation studies on dissolved species were undertaken with RuO2,xH2O and Ru° in nitric acid media. INTRODUCTION on two reactions. It consists in oxidizing a synthetic nitrato-nitrosyl-ruthenium complex (RuNO3+) in nitric Ruthenium is one of the chemical elements present acid, using Ag(II) electrochemically generated at a in solutions treated in nuclear fuel reprocessing based on platinum anode [4-7] as a strong oxidant. The volatile the PUREX process. It exhibits specific behavior during RuO4 formed is then desorbed from the electrolytic the process because of its relative abundance (6% of solution by flowing nitrogen and trapped in a suitable fission products), high activity (due to isotopes 103Ru liquid phase. -

Designing Ruthenium Anticancer Drugs: What Have We Learnt from the Key Drug Candidates?

inorganics Review Designing Ruthenium Anticancer Drugs: What Have We Learnt from the Key Drug Candidates? James P. C. Coverdale 1 , Thaisa Laroiya-McCarron 2 and Isolda Romero-Canelón 2,* 1 Department of Chemistry, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, UK; [email protected] 2 School of Pharmacy, Institute of Clinical Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 November 2018; Accepted: 13 February 2019; Published: 1 March 2019 Abstract: After nearly 20 years of research on the use of ruthenium in the fight against cancer, only two Ru(III) coordination complexes have advanced to clinical trials. During this time, the field has produced excellent candidate drugs with outstanding in vivo and in vitro activity; however, we have yet to find a ruthenium complex that would be a viable alternative to platinum drugs currently used in the clinic. We aimed to explore what we have learned from the most prominent complexes in the area, and to challenge new concepts in chemical design. Particularly relevant are studies involving NKP1339, NAMI-A, RM175, and RAPTA-C, which have paved the way for current research. We explored the development of the ruthenium anticancer field considering that the mechanism of action of complexes no longer focuses solely on DNA interactions, but explores a diverse range of cellular targets involving multiple chemical strategies. Keywords: ruthenium; anticancer; metal complex 1. Introduction Cancer is a major health burden in the developed world. Although many breakthroughs in biological targeted approaches have occurred (specifically, immunological therapy), an unmet clinical need remains for a large section of the patient population, so wide-spectrum chemotherapy agents are still required. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

Syntheses, Crystal Structures and Magnetic Properties of Rb Ruo and K

Syntheses, Crystal Structures and Magnetic Properties of Rb2RuO4 and K2RuO4 Dieter Fischera, Rudolf Hoppeb, Kailash M. Mogarea, and Martin Jansena a Stuttgart, Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Festk¨orperforschung, Heisenbergstraße 1, D-70569 Stuttgart, Germany b Institut f¨ur Anorganische und Analytische Chemie, Heinrich-Buff-Ring 58, D-35392 Gießen, Germany Reprint requests to Prof. Dr. Martin Jansen. Fax: +49-711/6891502. E-mail: [email protected] Z. Naturforsch. 60b, 1113 – 1117 (2005); received August 23, 2005 Potassium and rubidium oxoruthenates, A2RuO4, were synthesized from the alkali perox- ides/hyperoxides and ruthenium dioxide. Both compounds crystallize in the orthorhombic space group Pnma (no. 62), (K2RuO4: a = 7.673(2), b = 6.153(2) and c = 10.564(3) A,˚ Z = 4, 796 unique reflections, R = 3.5%; Rb2RuO4: a = 8.106(2), b = 6.270(1) and c = 11.039(2) A,˚ Z = 4, 889 unique reflections, R = 3.6%). The crystal structures, as determined from single crystal data, are of the β- K2SO4 type. Magnetic measurements reveal that both compounds are paramagnetic down to tem- peratures of around 60 K and further exhibit antiferromagnetic transitions, at around TN = 9 K for Rb2RuO4, and two transitions with TN = 14 K and 4 K for K2RuO4. The magnetic moments as de- termined applying Curie-Weiss law for both compounds are 2.68 µB, thus confirming the oxidation state +6 of ruthenium. Key words: Potassium and Rubidium Oxoruthenates, Ruthenium, Crystal Structure, Magnetic Properties Introduction the syntheses, crystal structure and magnetic properties of K2RuO4 and Rb2RuO4. Ruthenates crystallize in a rich variety of struc- ture types ranging from pyrochlores and hollandites Experimental Section to perovskite type phases, and exhibiting interesting Syntheses magnetic and electronic properties. -

Metal-Ligand Exchange Kinetics in Platinum and Ruthenium Complexes SIGNIFICANCE for EFFECTIVENESS AS ANTICANCER DRUGS

DOI: 10.1595/147106708X255987 Metal-Ligand Exchange Kinetics in Platinum and Ruthenium Complexes SIGNIFICANCE FOR EFFECTIVENESS AS ANTICANCER DRUGS By Jan Reedijk Leiden Institute of Chemistry, PO Box 9502, 2300 RA, Leiden, The Netherlands; E-mail: [email protected] Metal coordination compounds with ‘slow’metal-ligand exchange rates, comparable to those of cell division processes, often appear to be highly active in killing cancer cell lines. This is particularly marked in platinum and ruthenium complexes. Classical examples such as cisplatin, as well as very recent examples from the author’s and other work, will be discussed in detail, and in the context of the current knowledge of the mechanism of antitumour action. It is shown that even though much is known about the molecular mechanism of action of cisplatin, many challenging questions are left for future research. For the ruthenium anticancer drugs molecular mechanistic studies are only at the beginning. Mechanistic studies on both platinum and ruthenium compounds have, however, opened many new avenues of research that may lead to the design of completely new drugs. Since the appearance of the early review on cis- O O diamminedichloridoplatinum(II), commonly known NH2 Pt as cisplatin, 1, in this Journal (1), and its early success- NH2 es in the treatment of a variety of tumours, the topics O O of metal-DNA binding and platinum antitumour 3 Oxaliplatin chemistry have attracted considerable interest from chemists, pharmacologists, biochemists, biologists action of cisplatin and related drugs. This knowledge and medical researchers (2). In fact cisplatin and the has clearly resulted in much improved clinical later compounds carboplatin, 2, and oxaliplatin, 3, administration protocols, as well as motivated enjoy the status of the world’s best-selling anticancer research on other, related drugs containing transition drugs. -

Ruthenium Melt Catalysis PRODUCING CHEMICALS from SYNTHESIS GAS by John F

Ruthenium Melt Catalysis PRODUCING CHEMICALS FROM SYNTHESIS GAS By John F. Knifton Texaco Chemical Company, Austin, Texas A range of commodity chemicals and fuels can be generated directly from synthesis gas by ruthenium melt catalysis. Careful selection of the catalyst components enables a wide range of oxygenates to be produced, while other advantages of this flexible process include high productivity and the ease with which the products may be recovered and the catalyst recycled. In platinum-metal catalysed organic syn- present a renewable surface may avoid many of thesis, the primary purpose is to produce pure the problems of deactivation seen with con- products in high yields, with good ventional heterogeneous catalysts (4). reproducibility and ease of product isolation. Frequently, the melt is called upon to play While both homogeneous and heterogeneous more than one role in a chemical process. It catalysis systems may fulfill these roles in may, for example, simply act as a solvent for laboratory or industrial processes, an alterna- reactants and products; it may be a catalyst; it tive approach, that has many of the inherent may supply one or more of the reactants, as well advantages of both systems, is the use of molten as aid in controlling the heat of reaction. The salts as catalyst and/or reaction media. salts may be used singly (for example molten Molten salts may be classified into simple Na2C03, ZnCL or AlC13), or as eutectic ionic salts (for example the alkali and alkaline mixtures (such as Li2C03-Na2C03-K2C03, earth metal halides), simple and polymeric CuC1-CuCl2-KC1, and AlC13-BuPyC1) where oxyanionic salts (such as metal nitrates, car- the lower liquidus temperatures may be bonates, phosphates, borates), and salts contain- advantageous.