Our Forty-Dollar Horse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T5 Ranch Items 1 Mcclellan-US-Cavalry-Mule-Riding-Saddle-BRIGHT-RUSSET

Page 1 T5 Ranch Items 1 McClellan-US-Cavalry-Mule-Riding-Saddle-BRIGHT-RUSSET 2 U.S. CAV L.L.B Saddle Blanket 3 US-Cavalry Saddle 4 U.S Stamped Antique Tapaderos, Stirrups Leather Hood 5 U.S Arm Gas Mask 6 Antique Leather Rifle Scabbard 7 Wolseley Helmet 1879 8 Saddle Bags 9 U.S. Cavalry Saddle Bags 10 VINTAGE ANTIQUE METAL LADLE 1 Small and 1 Bigger 11 CAVALRY McClellan Saddle Horse Hair CINCH 12 Old Antique Cavalry Saddles and Tack 13 Military Cavalry English Horse Saddle 14 US Cavalry Horse Bit Stirrups 15 Old US Military Cavalry WWI Canvas Leather Horse Nose Feed Bag U.S. 16 Old Antique Cavalry Saddles 17 Old Antique Cavalry Saddles 18 Old Antique Cavalry Saddles and Tack 19 Antique Cavalry Tack 20 Antique Cavalry Saddles and Tack 21 Old Antique Cavalry Saddles and Tack 22 Antique Pack Mule Horse Saddle Military and Pads 23 Old Antique Leather Bag 24 U.S. Army Field Mess Gear Aluminum 25 WWI U.S. Army T-Handle, Entrench Tool, Shovel, (ETool) 26 WWI Pickelhaube spiked Leather Helmet Designed to deflect sword blows aimed at the head Page 2 27 Cleaning Rod for the Springfield 45-70 Carbine Hickory Scarce used in Garrison 1873-1884 28 Wooden Trapdoor Cleaning Rods and Cavalry Saddles 29 Antique Scythe, and Antique Crosscut Saws 30 Antique Crosscut Saws 31 Antique Wooden Skis 32 Antique Red & White 1930s Enamelware, Graniteware, Percolator Glass Lid Insert, Coffee Pots 33 Stromberg-Carlson Vintage Oak Wood Wall Telephone 34 U.S. Cavalry Leather Saddle Bags Dated 1917 35 Black U.S Stamped Cavalry Leather Saddle Bags 36 Military Hats (Stetson -

January 24,1885

PORTT, A NT) DAILY PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862·—VOL, 22. PORTLAND, S\TURDAY MORNING, OCTOBER 4, 1884- SlfffiittffiSffil PRICE THREE CENTS. ————MB————___ ____________ WKCIAL NOTICES. ROOMS TO LET. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, IN COLUMBUS. BCXTON AND ROLL». SERJEANT KELLY. the government in this case to show an act Cross Examination—Made no notée of what Published erery a*y (Snndayi excepted) by the whereby the State of Maine in its sovereign ownrr-Λ at the examination, bat this is what RENT—One famished front room. Shaw large PORTLAND Closing D>r Of Tfceir Vialh Annual capacity had ceded to the United States ex- I understood. FOR724 CONGRESS ST. octl-1 PUBLISHING COMPANY, and clusive over the after trial I heard a remark At 87 EIcbanOk Stkkbt, Poktlasd, Mb. Great Demonstrations in Mr. Fair. On Trial for the Alleged Man- jurisdiction territory in which Re direct—Soon TO Fort Popham is located. If this can be done about the testimony, bat I don't know that it BJE>ET. Blaine's Honor. The ninth annual cattle show and fair of slaughter of Frank Δ, Smith, tue question of jariidiction is settled. bad any influence in fixing the matter apon WEATHER IN DIPATIQNB. Mr. Lant «aid he did not wish at this mv mind. TTNFURNIShED room*at the St «ultan Hotel, the Bnxton and Hollis Agricultural Society is at point No. 19β Middle Street. Fort Popham. to discuss the question of jariediction. He Rev Frank Sewall, of Urbana, Ohio, testi- • thing of the The last pleasure seeker The Dining Boom will be thoroughly renorated Washington, Ôot. -

Snow Lantern

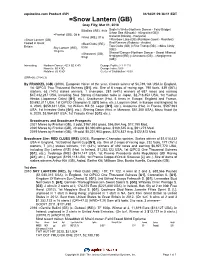

equineline.com Product 43PI 04/18/21 09:36:11 EDT =Snow Lantern (GB) Gray Filly; Mar 01, 2018 $Galileo (IRE), 98 b Sadler's Wells (Northern Dancer - Fairy Bridge) Urban Sea (Miswaki - Allegretta (GB)) =Frankel (GB), 08 b =Kind (IRE), 01 b Danehill (Danzig - Razyana) =Snow Lantern (GB) =Rainbow Lake (GB) (Rainbow Quest - Rockfest) Foaled in Great =Red Clubs (IRE), Red Ransom (Roberto - Arabia) Britain 03 br Two Clubs (GB) (=First Trump (GB) - =Miss Cindy Sky Lantern (IRE), (GB)) 10 gr/ro =Shawanni (GB), Shareef Dancer (Northern Dancer - Sweet Alliance) 93 gr Negligent (IRE) (=Ahonoora (GB) - =Negligence (GB)) Inbreeding: Northern Dancer: 4S X 5S X 4D Dosage Profile: 2 1 12 7 0 Nearctic: 5S X 5D Dosage Index: 0.69 Natalma: 5S X 5D Center of Distribution: -0.09 (SPR=90; CPI=5.3) By FRANKEL (GB) (2008). European Horse of the year, Classic winner of $4,789,144 USA in England, 1st QIPCO Two Thousand Guineas [G1], etc. Sire of 6 crops of racing age, 790 foals, 439 (56%) starters, 63 (14%) stakes winners, 1 champion, 281 (64%) winners of 687 races and earning $47,432,287 USA, including Soul Stirring (Champion twice in Japan, $2,718,853 USA, 1st Yushun Himba (Japanese Oaks) [G1], etc.), Cracksman (Hwt. 5 times in Europe, England and France, $3,692,311 USA, 1st QIPCO Champion S. [G1] twice, etc.), Logician (Hwt. in Europe and England, to 4, 2020, $659,331 USA, 1st William Hill St. Leger [G1], etc.), Anapurna (Hwt. in France, $597,963 USA, 1st Investec Oaks [G1], etc.), Shining Dawn (Hwt. -

262 Camas Park & Glenvale Studs

262 Camas Park & Glenvale Studs 262 Sadler's Wells Montjeu Floripedes CAMELOT Kingmambo N. Tarfah (IRE) Fickle Woodman Mujtahid bay colt 11/02/2016 SPLENDID Mesmerize 1995 (IRE) Braneakins Sallust 1980 Balidaress E.B.F./B.C. Nominated CAMELOT (2009), 6 wins at 2 to 4 years, Dubai Duty Free Irish Derby (Gr.1), Investec Derby S.(Gr.1), Qipco 2000 Guineas (Gr.1), Racing Post Trophy (Gr.1), High Chaparral EBF Mooresbridge S.(Gr.3), 2nd Ladbrokes St Leger S.(Gr.1), Tattersalls Gold Cup (Gr.1). Stud in 2014. First crop now 2 year olds. 1st dam SPLENDID, placed once at 2 years in GB. Dam of 13 foals, 12 of racing age, 7 winners incl. : Bohunk, (c. Polish Numbers), 5 wins in USA, $95,107, 2nd St. Paul S.(L.). Fanditha (f. Danehill Dancer), 4 wins at 2 to 5 years in GB, £40,385, 2nd Hoppings St.(L.), 4th Ormonde St.(Gr.3). Dam of a winner. Lord High Admiral, (c., Galileo), 1 win, placed once at 2 years in IRE, 2nd Killavullan St.(Gr.3). N., (f.2015, Camelot), in training in GB. 2nd dam BRANEAKINS, 3 wins at 3 years. Dam of 13 foals, 4 winners incl. : PEKING OPERA, (c., Sadler's Wells), 2 wins at 2 and 3 years in GB, Warren St. at Epsom (L.), 3rd Chester Vase (Gr.3). Sire. Sadler's Fly, (f., Sadler's Wells). Dam of Rich And Handsome (TUR) (8 wins, 2nd Tali Calbatur L., 3rd Tay Deneme (2000 Guineas) L.). Elegant, (f., Marju). Dam of Eloquently (1 win, 3rd Miesque S.Gr.3). -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Horses Need Extra TLC During Cold, Wet Winter Weather

CA.UKY.EDU/EQUINE ❙ THEHORSE.COM ❙ JANUARY 2019 BROUGHT TO YOU BY which can help them maintain body Horses Need Extra TLC During temperature.” If owners are unsure of their hay qual- Cold, Wet Winter Weather ity, slowly adding a daily concentrate can help provide a complete ration. he 2018-2019 winter has “Horses have three basic needs— Many horse owners use blankets, served up roller coaster shelter, feed, and water,” said Bob which can be helpful but also require Coleman, PhD, horse specialist for the extra attention. T temperatures and record University of Kentucky (UK) College of “You need to remove the blanket peri- precipitation in Kentucky. Our Agriculture, Food and Environment, odically to groom and check the horse’s equine friends are quite adap- in Lexington. “You can easily manage coat,” Coleman said. “We have some horses outside, but you’ll have to provide extreme temperature variations, and if tive to these variations, but horse a few creature comforts.” that blanket gets wet or if it warms up owners must provide additional Shelter should provide protection and traps moisture from the horse sweat- care to help animals cope and from the wind and the different forms ing, it could be detrimental to the horse’s thrive when temperatures dip of precipitation Kentucky sees in winter, health and coat condition. So, if you such as freezing rain, sleet, snow, and must use blankets, make sure you check low and are accompanied by wet ice. Coleman said horses’ hair coats can the horse often.” and windy conditions. effectively protect them from cold tem- It’s also important to ensure blankets peratures, but they’re less able fit properly. -

A Police Whistleblower in a Corrupt Political System

A police whistleblower in a corrupt political system Frank Scott Both major political parties in West Australia espouse open and accountable government when they are in opposition, however once their side of politics is able to form Government, the only thing that changes is that they move to the opposite side of the Chamber and their roles are merely reversed. The opposition loves the whistleblower while the government of the day loathes them. It was therefore refreshing to see that in 2001 when the newly appointed Attorney General in the Labor government, Mr Jim McGinty, promised that his Government would introduce whistleblower protection legislation by the end of that year. He stated that his legislation would protect those whistleblowers who suffered victimization and would offer some provisions to allow them to seek compensation. How shallow those words were; here we are some sixteen years later and yet no such legislation has been introduced. Below I have written about the effects I suffered from trying to expose corrupt senior police officers and the trauma and victimization I suffered which led to the loss of my livelihood. Whilst my efforts to expose corrupt police officers made me totally unemployable, those senior officers who were subject of my allegations were promoted and in two cases were awarded with an Australian Police Medal. I describe my experiences in the following pages in the form of a letter to West Australian parliamentarian Rob Johnson. See also my article “The rise of an organised bikie crime gang,” September 2017, http://www.bmartin.cc/dissent/documents/Scott17b.pdf 1 Hon. -

A Social and Cultural History of the New Zealand Horse

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. A SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE NEW ZEALAND HORSE CAROLYN JEAN MINCHAM 2008 E.J. Brock, ‘Traducer’ from New Zealand Country Journal.4:1 (1880). A Social and Cultural History of the New Zealand Horse A Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Massey University, Albany, New Zealand Carolyn Jean Mincham 2008 i Abstract Both in the present and the past, horses have a strong presence in New Zealand society and culture. The country’s temperate climate and colonial environment allowed horses to flourish and accordingly became accessible to a wide range of people. Horses acted as an agent of colonisation for their role in shaping the landscape and fostering relationships between coloniser and colonised. Imported horses and the traditions associated with them, served to maintain a cultural link between Great Britain and her colony, a characteristic that continued well into the twentieth century. Not all of these transplanted readily to the colonial frontier and so they were modified to suit the land and its people. There are a number of horses that have meaning to this country. The journey horse, sport horse, work horse, warhorse, wild horse, pony and Māori horse have all contributed to the creation of ideas about community and nationhood. How these horses are represented in history, literature and imagery reveal much of the attitudes, values, aspirations and anxieties of the times. -

Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery 1

FAIRFIELD COUNTY CEMETERIES VOLUME II (Church Cemeteries in the Eastern Section of the County) Mt. Olivet Presbyterian Church This book covers information on graves found in church cemeteries located in the eastern section of Fairfield County, South Carolina as of January 1, 2008. It also includes information on graves that were not found in this survey. Information on these unfound graves is from an earlier survey or from obituaries. These unfound graves are noted with the source of the information. Jonathan E. Davis July 1, 2008 Map iii Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery 1 Bethesda Methodist Church Cemetery 26 Centerville Cemetery 34 Concord Presbyterian Church Cemetery 43 Longtown Baptist Church Cemetery 62 Longtown Presbyterian Church Cemetery 65 Mt. Olivet Presbyterian Church Cemetery 73 Mt. Zion Baptist Church Cemetery – New 86 Mt. Zion Baptist Church Cemetery – Old 91 New Buffalo Cemetery 92 Old Fellowship Presbyterian Church Cemetery 93 Pine Grove Cemetery 95 Ruff Chapel Cemetery 97 Sawney’s Creek Baptist Church Cemetery – New 99 Sawney’s Creek Baptist Church Cemetery – Old 102 St. Stephens Episcopal Church Cemetery 112 White Oak A. R. P. Church Cemetery 119 Index 125 ii iii Aimwell Presbyterian Church Cemetery This cemetery is located on Highway 34 about 1 mile west of Ridgeway. Albert, Charlie Anderson, Joseph R. November 27, 1911 – October 25, 1977 1912 – 1966 Albert, Jessie L. Anderson, Margaret E. December 19, 1914 – June 29, 1986 September 22, 1887 – September 16, 1979 Albert, Liza Mae Arndt, Frances C. December 17, 1913 – October 22, 1999 June 16, 1922 – May 27, 2003 Albert, Lois Smith Arndt, Robert D., Sr. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

Vol. 23 • No. 5 the Mid-South Equine Newsmagazine Since 1992 JANUARY 2013

FREE HH00rrsseeRReevviieeww Vol. 23 • No. 5 The Mid-South Equine Newsmagazine Since 1992 JANUARY 2013 Annual Stallion Issue Topsail Whiz, the first and only, National Reining Horse Association (NRHA) Nine Million Dollar Sire. 2. January, 2013 • Mid-South Horse Review www.midsouthhorsereview.com Young Entry Book Nook The Brookmeade Young HHoorrssee RReevviieeww Equus Charta, LLC Riders Series Copyright 2013 Book Review by Leigh Ballard sees some potential in the horse. It becomes 6220 Greenlee #7 Sarah’s task to prove to her parents that he P.O. Box 594 • Arlington, TN The first two books in the Brookmeade can be safe and manageable. The first book Young Riders Series are Crown Prince and is the story of his progress. Sarah’s efforts 38002-0594 Crown Prince Challenged by Linda Snow are somewhat thwarted by jealousy from a 901-867-1755 McLoon. The books tell the story of an off- “mean girl” who has problems of her own. Publishers: track Thoroughbred, Crown Prince, and his There is a surprise tragic event near the end teen rider, Sarah Wagner. Sarah is a good of the first book caused by the jealous girl, Tommy & Nancy Brannon Hallie Rush of Showcase Equestrian rider, but because of an automobile accident which is a wake up call for everybody. Center, LLC and Virginia Blue at the that severely injured her mother, the family Staff : International Winter Festival, St. Louis, can’t afford for Sarah to own a horse and be Andrea Gilbert MO. The pair were Medium Pony Re - a competitive show rider. Sarah works to Leigh Ballard serve Champions, qualifiying for 2013 pay for her riding lessons, and she looks for - Graphics: Lauren Pigford Pony Finals. -

There Was Movement at the Station, for the Word Had

There was movement at the station, for the word had passed around That the colt from old Regret had got away, The Man From And had joined the wild bush horses - he was worth a thousand pound, So all the cracks had gathered to the fray. Snowy River All the tried and noted riders from the stations near and far Had mustered at the homestead overnight, For the bushmen love hard riding where the wild bush horses are, And the stockhorse snuffs the battle with delight. There was Harrison, who made his pile when Pardon won the cup, The old man with his hair as white as snow; But few could ride beside him when his blood was fairly up - He would go wherever horse and man could go. And Clancy of the Overflow came down to lend a hand, No better horseman ever held the reins; For never horse could throw him while the saddle girths would stand, He learnt to ride while droving on the plains. And one was there, a stripling on a small and weedy beast, He was something like a racehorse undersized, With a touch of Timor pony - three parts thoroughbred at least - And such as are by mountain horsemen prized. He was hard and tough and wiry - just the sort that won’t say die - There was courage in his quick impatient tread; And he bore the badge of gameness in his bright and fiery eye, And the proud and lofty carriage of his head. But still so slight and weedy, one would doubt his power to stay, And the old man said, “That horse will never do For a long a tiring gallop - lad, you’d better stop away, Those hills are far too rough for such as you.” So he waited sad and wistful - only Clancy stood his friend - “I think we ought to let him come,” he said; “I warrant he’ll be with us when he’s wanted at the end, AIRVOLUTION 1 For both his horse and he are mountain bred.