Fledgling South African Anglicanism and the Roots of Ritualism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the 79Th Diocesan Convention

EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER 2010 JOURNAL OF CONVENTION AND THE CONSTITUTION AND CANONS Journal of the Proceedings of the Seventy-Ninth Annual Convention of the EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER held at The Hyatt Regency Rochester Rochester, New York November 5 & 6, 2010 together with the Elected Bodies, Clergy Canonically Resident, Diocesan Reports, Parochial Statistics Constitution and Canons 2010 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One -- Organization Pages Diocesan Organization 4 Districts of the Diocese 13 Clergy in Order of Canonical Residence 15 Addresses of Lay Members and Elected Bodies 21 Parishes and Missions 23 Part Two -- Annual Diocesan Convention Clerical and Lay Deputies 26 Bishop’s Address 31 Official Acts of the Bishop 38 Bishop’s Discretionary Fund 42 Licenses 44 Journal of Convention 52 Diocesan Budget 70 Clergy and Lay Salary Scales 78 Part Three -- Reports Report of Commission on Ministry 84 Diocesan Council Minutes 85 Standing Committee Report 90 Report of the Trustees 92 Reports of Other Departments and Committees 93 Diocesan Audit 120 Part Four -- Parochial Statistics Parochial Statistics 137 Constitution and Canons 141 3 PART ONE ORGANIZATION 4 THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER 935 East Avenue Rochester, New York 14607 Telephone: 585-473-2977 Fax: 585-473-3195 or 585-473-5414 OFFICERS Bishop of the Diocese The Rt. Rev. Prince G. Singh Chancellor Registrar Philip R. Fileri, Esq. Ms. Nancy Bell Harter, Secrest &Emery, LLP 6 Goldenhill Lane 1600 Bausch & Lomb Place Brockport, NY 14420 Rochester, NY 14607 585-637-0428 585-232-6500 e-mail: [email protected] FAX: 585-232-2152 e-mail: [email protected] Assistant Registrar Ms. -

YVES CONGAR's THEOLOGY of LAITY and MINISTRIES and ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION in the UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to Th

YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Alan D. Mostrom UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2018 YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. APPROVED BY: ___________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor ___________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Timothy R. Gabrielli, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader, Seton Hill University ___________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ William H. Johnston, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Alan D. Mostrom All rights reserved 2018 iii ABSTRACT YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. Yves Congar’s theology of the laity and ministries is unified on the basis of his adaptation of Christ’s triplex munera to the laity and his specification of ministry as one aspect of the laity’s participation in Christ’s triplex munera. The seminal insight of Congar’s adaptation of the triplex munera is illumined by situating his work within his historical and ecclesiological context. The U.S. reception of Congar’s work on the laity and ministries, however, evinces that Congar’s principle insight has received a mixed reception by Catholic theologians in the United States due to their own historical context as well as their specific constructive theological concerns over the laity’s secularity, or the priority given to lay ministry over the notion of a laity. -

Robert D. Hawkins

LEX OR A NDI LEX CREDENDI THE CON F ESSION al INDI ff ERENCE TO AL TITUDE Robert D. Hawkins t astounds me that, in the twenty-two years I have shared Catholics, as the Ritualists were known, formed the Church Iresponsibility for the liturgical formation of seminarians, of England Protection Society (1859), renamed the English I have heard Lutherans invoke the terms “high church” Church Union (1860), to challenge the authority of English and “low church” as if they actually describe with clar- civil law to determine ecclesiastical and liturgical practice.1 ity ministerial positions regarding worship. It is assumed The Church Association (1865) was formed to prosecute in that I am “high church” because I teach worship and know civil court the “catholic innovations.” Five Anglo-Catholic how to fire up a censer. On occasion I hear acquaintances priests were jailed following the 1874 enactment of the mutter vituperatively about “low church” types, apparently Public Worship Regulation Act for refusing to abide by civil ecclesiological life forms not far removed from amoebae. court injunctions regarding liturgical practices. Such prac- On the other hand, a history of the South Carolina Synod tices included the use of altar crosses, candlesticks, stoles included a passing remark about liturgical matters which with embroidered crosses, bowing, genuflecting, or the use historically had been looked upon in the region with no lit- of the sign of the cross in blessing their congregations.2 tle suspicion. It was feared upon my appointment, I sense, For readers whose ecclesiological sense is formed by that my supposed “high churchmanship” would distract notions about the separation of church and state, such the seminarians from the rigors of pastoral ministry into prosecution seems mind-boggling, if not ludicrous. -

Towards an Assessment of Fresh Expressions of Church in Acsa

TOWARDS AN ASSESSMENT OF FRESH EXPRESSIONS OF CHURCH IN ACSA (THE ANGLICAN CHURCH OF SOUTHERN AFRICA) THROUGH AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE COMMUNITY SUPPER AT ST PETER’S CHURCH IN MOWBRAY, CAPE TOWN REVD BENJAMIN JAMES ALDOUS DISSERTATION PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORAL PHILOSOPHY IN THEOLOGY (PRACTICAL THEOLOGY) IN THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH APRIL 2019 SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IAN NELL Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: April 2019 Copyright © 2019 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Fresh Expressions of Church is a growing mission shaped response to the decline of mainline churches in the West. Academic reflection on the Fresh Expressions movement in the UK and the global North has begun to flourish. No such reflection, of any scope, exists in the South African context. This research asks if the Fresh Expressions of Church movement is an appropriate response to decline and church planting initiatives in the Anglican Church in South Africa. It also seeks to ask what an authentic contextual Fresh Expression of Church might look like. Are existing Fresh Expression of Church authentic responses to church planting in a postcolonial and post-Apartheid terrain? Following the work of the ecclesiology and ethnography network the author presents an ethnographic study of The Community Supper at St Peter’s Mowbray, Cape Town. -

Architects of Communion Guide for Parish Development

• Architects of Communion Guide for Parish Development The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter 7730 Westview, Houston, Texas 77055 | 713.609.9292 www.ordinariate.net DECREE Whereas the Guide for Parish Development newly created for use in the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter provides an essential tool for evaluating the development of our communities from their earliest beginnings as groups in formation through to their canonical erection as Parishes; Whereas the Apostolic Constitution Anglicanorum coetibus established the Ordinariates for the purpose of unity and “organizing our lives around the Parish… [as] the principal indicator of our commitment to full communion”; Whereas the Guide was reviewed and amended by the Governing Council which, on May 9, 2016, approved it and recommended that it be promulgated throughout the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter; I therefore accept the text and promulgate the Guide for Parish Development for the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter as the evaluative instrument for guiding parochial development. Given in Houston, on this 31st day of May, in the year of Our Lord 2016, the Feast of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. +STEVEN J. LOPES, STD Bishop of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter Architects of Communion Guide for Parish Development Introduction he clergy and faithful of the Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter are called to be architects of communion, simultaneously preserving the distinctiveness and integrity of their communities while demonstrating commitment to act in communion with the broader Church. -

Chapter 4: BISHOP ROBERT GRAY – an ASSESSMENT

A clash of churchmanship? Robert Gray and the Evangelical Anglicans 1847 – 1872 Alan Peter Beckman Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Church and Dogma History) at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University. Supervisor: Dr J Newby Co-supervisor: Dr P H Fick May 2011. 2 ABSTRACT This study investigates the initial causes of Anglican division in South Africa in order to assess whether the three Evangelical parishes in the Cape Peninsula were justified in declining to join the Church of the Province of South Africa when it was formally constituted as a voluntary association in January 1870. The research covered the following: Background to the period in England and at the Cape, based on the histories pertinent to the period; An assessment of the differences in churchmanship between the Evangelicals and the Anglo-Catholics, through study of the applicable literature; A critical assessment of the character, churchmanship, aims, and actions of the first bishop of Cape Town, Robert Gray, drawn from the two-volume biography of his life, his journals and documents obtained in the archives; An analysis of the disputes between Bishop Gray and two Evangelical clergymen, analyzed from the published correspondence and archive material. The conclusion of the study is that the differences in churchmanship between the Evangelicals and the Anglo Catholics were very substantial and when coupled with the character, aims and actions of Bishop Gray, left the Evangelicals with little option but to decline the invitation to join his voluntary association. KEY WORDS Anglican Evangelical Anglo-Catholic Tractarian Churchmanship 3 UITREKSEL In hierdie studie word die aanvanklike oorsake van Anglikaanse verdeeldheid in Suid-Afrika ondersoek ten einde te bepaal of die drie Evangeliese gemeentes in die Kaapse Skiereiland geregverdig was om nie aan te sluit by die Church of the Province of South Africa nie toe dit formeel gekonstitueer was as 'n vrywillige vereniging in Januarie 1870. -

Forms of Address for Clergy the Correct Forms of Address for All Orders of the Anglican Ministry Are As Follows

Forms of Address for Clergy The correct forms of address for all Orders of the Anglican Ministry are as follows: Archbishops In the Canadian Anglican Church there are 4 Ecclesiastical Provinces each headed by an Archbishop. All Archbishops are Metropolitans of an Ecclesiastical Province, but Archbishops of their own Diocese. Use "Metropolitan of Ontario" if your business concerns the Ecclesiastical Province, or "Archbishop of [Diocese]" if your business concerns the Diocese. The Primate of the Anglican Church of Canada is also an Archbishop. The Primate is addressed as The Most Reverend Linda Nicholls, Primate, Anglican Church of Canada. 1. Verbal: "Your Grace" or "Archbishop Germond" 2. Letter: Your Grace or Dear Archbishop Germond 3. Envelope: The Most Reverend Anne Germond, Metropolitan of Ontario Archbishop of Algoma Bishops 1. Verbal: "Bishop Asbil" 2. Letter: Dear Bishop Asbil 3. Envelope: The Right Reverend Andrew J. Asbil Bishop of Toronto In the Diocese of Toronto there are Area Bishops (four other than the Diocesan); envelopes should be addressed: The Rt. Rev. Riscylla Shaw [for example] Area Bishop of Trent Durham [Area] in the Diocese of Toronto Deans In each Diocese in the Anglican Church of Canada there is one Cathedral and one Dean. 1. Verbal: "Dean Vail" or “Mr. Dean” 2. Letter: Dear Dean Vail or Dear Mr. Dean 3. Envelope: The Very Reverend Stephen Vail, Dean of Toronto In the Diocese of Toronto the Dean is also the Rector of the Cathedral. Envelope: The Very Reverend Stephen Vail, Dean and Rector St. James Cathedral Archdeacons Canons 1. Verbal: "Archdeacon Smith" 1. Verbal: "Canon Smith" 2. -

The Anglican Diocese of Natal a Saga of Division and Healing the New Cathedral of the Holy Nativity in Pietermaritzburg Was Dedicated in November of This Year

43 The Anglican Diocese of Natal A Saga of Division and Healing The new cathedral of the Holy Nativity in Pietermaritzburg was dedicated in November of this year. The vast cylinder of red brick stands next to the smaller neo-gothic shale and slate church of St Peter which was consecrated in 1857. The period of 124 years between the two events carries a tale of division which in its lurid details is as ugly as the subsequent process of reunion has been fruitful. Now follows the saga of division and healing. In 1857 when St Peter's was first opened for worship there was already tension between the dean and bishop, though it was still below the surface. The private correspondence of Bishop John William Colenso shows that he would have preferred his former college friend, the Reverend T. Patterson Ferguson, to be dean. Dean James Green on the other hand was writing to Metopolitan Robert Gray of Cape Town and complaining about Colenso's methods of administering the diocese. The disagreements between the two men became public during the following year, 1858. Dean Green, together with Canon John David Jenkins, walked out. of the cathedral when they heard Colenso preaching about the theology of the eucharist. Although they later returned, Colenso had to administer holy communion unassisted. Later in the year the same men, together with Archdeacon C.F. Mackenzie and the Reverend Robert Robertson, walked out of a conference of clergy and laity of the diocese. On each occasion the dean and bishop were differing on points of detail. -

Piety of the Laity in Byzantium

Piety of the Laity in Byzantium Nicholas Marinides Over fifty years ago the historian Norman Baynes noted a dual ethic of lay and monastic ways of life in Byzantium, “two standards, one of the ordinary Christian living his life in the work-a-day world and the other standard for those who were haunted by the words of Christ: ‘if thou wouldst be perfect’”1. This dualism still faces the Orthodox Christian who is steeped in the ascetical ethos of the Fathers of the Church and has the opportunity to visit flourishing Orthodox monasteries in Europe and America. The event that, for me, crystallized the question of this duality and led me to make it the focus of my dissertation was that great classic of the Orthodox monastic tradition, the Ladder of Divine Ascent by John Klimakos, abbot of Mt. Sinai. The Ladder is a work of extraordinary literary beauty and uncompromising monastic austerity. I wondered how this paradoxical work could both attract the lay faithful and keep them at a distance. If the Ladder is supposed to be climbed by monks, do laypeople have to remain eternally at its bottom step gazing up? Ecclesiologically speaking, how can the Church be One and Holy, if such a differentiation makes it impossible for all to share a single consciousness of Christian holiness? By now some of you may be wondering why I am discussing the relations of laypeople to monks and not to clergy. My reasons are largely historical. The role of the clergy was certainly important in Byzantium, but it was the holy monk who captured the Byzantine imagination and was, as Baynes says, “the realization of the Byzantine ideal.”2 Having through extraordinary ascetic effort achieved a state of untroubled tranquility, he transmitted God’s favor to the laypeople, who toiled away in a life of socio-economic duty. -

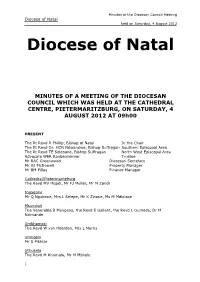

Diocese of Natal Held on Saturday, 4 August 2012

Minutes of the Diocesan Council Meeting Diocese of Natal held on Saturday, 4 August 2012 Diocese of Natal MINUTES OF A MEETING OF THE DIOCESAN COUNCIL WHICH WAS HELD AT THE CATHEDRAL CENTRE, PIETERMARITZBURG, ON SATURDAY, 4 AUGUST 2012 AT 09h00 PRESENT The Rt Revd R Phillip, Bishop of Natal In the Chair The Rt Revd Dr. HCN Ndwandwe, Bishop Suffragan Southern Episcopal Area The Rt Revd TE Seleoane, Bishop Suffragan North West Episcopal Area Advocate WER Raubenheimer Trustee Mr RAC Greenwood Diocesan Secretary Mr GJ McDowell Property Manager Mr BM Pillay Finance Manager Cathedral/Pietermaritzburg The Revd MV Mqadi, Mr FJ Muller, Mr M Zondi Ingagane Mr Q Ngubane, Mrs L Selepe, Mr K Zwane, Ms M Mdlalose Msunduzi The Venerable B Mangena, the Revd E Gallant, the Revd L Gumede, Dr M Nzimande Umkhomazi The Revd W van Heerden, Mrs L Morris Umngeni Mr S Mkhize Uthukela The Revd M Khumalo, Mr M Mbhele 1 Minutes of the Diocesan Council Meeting Diocese of Natal held on Saturday, 4 August 2012 Durban The Venerable GM Laban, Mr D Trudgeon Durban Ridge The Venerable NM Msimango, the Revd T Tembe, Mr W Abrahams Durban South The Venerable WP Dludla, the Revd M Zondi, Mr W Joshua, Mr A Mvelase, the Revd M Zondi Lovu The Revd M Wishart, the Revd M Silva, Mr A Cooper North Coast The Venerable PC Houston, the Revd C Mahaye, Ms P Nzuza 2 Minutes of the Diocesan Council Meeting Diocese of Natal held on Saturday, 4 August 2012 North Durban The Venerable M Skevington Pinetown The Venerable Dr AE Warmback, the Revd G Thompson, Ms T Maseatile, Mr E Pines, Mr S Zondi Umzimkhulu The Venerable P Nene, Ms L Cebisa Diocesan Committees The Revd Canon Dr P Wyngaard, The Revd GA Thompson, Mrs R Phillip, Ms Z Mbongwe, Mrs N Vilakazi, Mr K Dube, Ms Z Hlatshwayo 1. -

“Beyond the Character of the Times”: Anglican Revivalists in Eighteenth-Century Virginia

“Beyond the Character of the Times”: Anglican Revivalists in Eighteenth-Century Virginia By Frances Watson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Liberty University 2021 Table of Contents Introduction 2 Chapter One: Beyond Evangelical – Anglican Revivalists 14 Chapter Two: Beyond Tolerant – Spreading Evangelicalism 34 Chapter Three: Beyond Patriotic – Proponents of Liberty 55 Conclusion 69 Bibliography 77 ~ 1 ~ Introduction While preaching Devereux Jarratt’s funeral service, Francis Asbury described him thus: “He was a faithful and successful preacher. He had witnessed four or five periodical revivals of religion in his parish. When he began his labours, there was no other, that he knew of, evangelical minister in all the province!”1 However, at the time of his death, Jarratt would be one of a growing number of Evangelical Anglican ministers in the province of Virginia. Although Anglicanism remained the established church for the first twenty three years of Jarratt’s ministry, the Great Awakening forcefully brought the message of Evangelicalism to the colonies. As the American Revolution neared, new ideas about political and religious freedom arose, and Evangelical dissenters continued to grow in numbers. Into this scene stepped Jarratt, his friend Archibald McRobert, and his student Charles Clay. These three men would distinguish themselves from other Anglican clergymen by emulating the characteristics of the Great Awakening in their ministries, showing tolerance in their relationships with other religious groups, and providing support for American freedoms. Devereux Jarratt, Archibald McRobert, and Charles Clay all lived and mainly ministered to communities in the Piedmont area. -

Aspects of Anglicanism

Aspects of Anglicanism Today's Church & Today's World G. J. C. MARCHANT Section VI After the wide-ranging symposium of the articles in the previous five sections, the final three essays of Section VI face a question both elusive and challenging. What is Anglicanism, that we have been surveying in all its breadth and length? The question might be regarded as exhibiting those anxiety traits that have caused almost all institutions, assumptions and principles-social, moral or religious-to be re-examined rigorously during the post-war decades. Anyone actually flying in a plane, while perhaps wondering whether the wings will stay on, is hardly likely to ask whether it is working correctly to aerodynamic principles. The nagging introspective enquiry that keeps surfacing in these three last articles is, however, of this order: not whether Anglicanism is wise or right in this or that; nor what might be new approaches, formulations, realignments, growth points or other developmental themes. These of course are there. But the real matter that underlies the three is: What is peculiar, native, identifying, about Anglican churchmanship, now that it has spread beyond the Anglo Saxon, British racial origins to embrace great provinces of Asian, African and South American peoples? It is more explicit in the first of the three articles, 'On Being Anglican', by Bishop Stephen Neill; and it is obviously haunting the third by Bishop John Howe, the Secretary-General of the Anglican Consultative Council (ACC) in his 'Anglican Patterns'; but it is also iJnplicit in the discussion by Bishop Oliver Tomkins in the second, 'Anglican Christianity and Ecumenism'.