Island Studies Journal, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2016, Pp. 35-56. in the Azores, Looking for the Regions of Knowing ABSTRACT: This Multi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

São Jorge Terceira Pico Faial Graciosa São Miguel Santa Maria

27°28'0"W 27°26'0"W 27°24'0"W 27°22'0"W 27°20'0"W 27°18'0"W 27°16'0"W 27°14'0"W 27°12'0"W 27°10'0"W 27°8'0"W 27°6'0"W 27°4'0"W 27°2'0"W 27°0'0"W 26°58'0"W o 38°52'0"N 38°52'0"N 38°50'0"N 38°50'0"N Ponta dos Biscoitos Cais dos Biscoitos BISCOITOS Ponta das Quatro RibeirasPonta do Mistério a Sto António MATIAS SIMÃO p 38°48'0"N a 0 Ponta da Furna L 38°48'0"N 0 Terreiro da D. Rosa Canada Brás da Silva Canada da Salga Biscoito Bravo Ponta da Lagoa Canada do Porto Rua Longa Baía das Quatro Ribeiras Portal da Cruz Ribeira dos Gatos Achadas Ribeira da Lapa Forno de Sto António Boqueirão Canada do Saco Lagoa da Fajãzinha ALTARES e o d o RAMINHO l ã c o BISCOITOS Farroco i d ALTARES b Sta CatarinaCanada do Caldeiro i Baixa da Caldeira P v e G r Ao Lugar R o G r e o d r Arrochela Canada do Cruzeiro t S Canada da Estaca o a 0 0 a t e CANADA DO VELHO a a d d BISCOITOS TI Rebentão do Bom Jesus d 0 a Ponta da Forcada RAMINHO NE a Baiões n a Canada do Rego a d Ponta das Escaleiras d d a RAMINHO R a C a n s n a 0 Canada da Bernarda ib QUATRO RIBEIRAS a Canada dos Morros a a n . -

Catálogo 2018

TERCEIRA ISLAND - The Lilac Island - Elliptic in shape, Terceira covers an area of 402 sq. km, is 29 km at its longest and 17.5 km at its widest. The island is a plateau, with the Serra do Cume to the east, the Serra do Labaçal in the centre (rising to 808m), and the Serra da Santa Bárbara (rising to 1,021m) to the west. Angra do Heroismo, with its origins in the late 15th century, has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is a picture book town of imposing townhouses and cobbled streets seemingly untouched by time. The best views of this once prosperous trading centre are from Monte Brasil across the harbour. The west coast harbours a host of villages and the wilder, with volcanic caves which are a further invitation to discover the subterranean mysteries. Natal Caves and Algar do Carvão considered a geological Nature Reserve is formed by caves of up 100 metres in depth, with majestic stalactites and stalagmites and inner lake. Praia da Vitoria, to the east, with its sandy beach is a charming small town and, inland, the views from the 500m high point of the Serra do Cume, over the gigantic quilt made up of green pastures separated by black volcanic stone walls, quite breathtaking. Terceira caters to all interests from golf, exploring volcanoes, walking, swimming in natural rock pools and visiting the sixty-eight 19th century ‘Impérios’, (small chapels of the Holy Spirit), which are scattered throughout the island. Then there are the colourful festivals and street bullfights (they pad the bulls’ horns and bulls are never killed) where the only casualty is young men’s wounded pride. -

Analysis and Definition of Potential New Areas for Viticulture in the Azores (Portugal)

1 Analysis and definition of potential new areas for viticulture in the Azores 2 (Portugal) 3 J. Madruga1, E. B. Azevedo1,2, J. F. Sampaio1, F. Fernandes2, F. Reis2, and J. Pinheiro1 4 1CITA_A, Research Center of Agrarian Sciences of the University of the Azores. 9700-042 Angra do Heroísmo, 5 Portugal 6 2CCMMG, Research Center for Climate, Meteorology and Global Change, University of the Azores. 9700-042 7 Angra do Heroísmo, Portugal 8 Abstract 9 Vineyards in the Azores have been traditionally settled on lava field “terroirs” but the practical 10 limitations of mechanization and high demand on man labor imposed by the typical micro parcel 11 structure of these vineyards contradict the sustainability of these areas for wine production, except 12 under government policies of heavy financial support. Besides the traditional vineyards there are 13 significant areas in some of the islands whose soils, climate and physiographic characteristics 14 suggest a potential for wine production that deserves to be object of an assessment, with a view to 15 the development of new vineyard areas offering conditions for a better management and 16 sustainability. 17 The landscape zoning approach for the present study was based in a Geographic Information 18 System (GIS) analysis incorporating factors related to climate, topography and soils. Three thermal 19 intervals referred to climate maturity groups were defined and combined with a single slope interval 20 of 0–15% to exclude the landscape units above this limit. Over this resulting composite grid, the soils 21 were than selectively cartographed through the exclusion of the soil units not fulfilling the suitability 22 criteria. -

An Appointment with History, Tradition and Flavours

AN APPOINTMENT WITH HISTORY, TRADITION AND FLAVOURS UNIÃO EUROPEIA GOVERNO Fundo Europeu de DOS AÇORES Desenvolvimento Regional 36º 55’ 44’’ N, 25º 01’ 02’’ W - Azores, PORTUGAL INTANGIBLE HERITAGE balconies. Azorean traditions, characterised by their festive and cheerful spirit, Azorean people have a peculiar way of being and living due to the take several forms. The street bullfight tradition, which is especially geographic and climate conditions of each island, in addition to important on Terceira Island, goes back to the islands’ first settlers and volcanism, insularity and the influence of several settlers, who did all the Spanish presence in the Azores. Carnival is another relevant tradition they could to adjust to these constraints. By doing so, they created a in the Azores, varying from island to island. There is typical season food TANGIBLE HERITAGE facilities, namely the Whale Factory of Boqueirão, on Flores Island, the cultural identity which expresses itself through traditions, art, shows, and music and, on São Miguel Island, there are gala events. Carnival is Old Whale Factory of Porto Pim, on Faial Island, and the Environmental social habits, rituals, religious manifestations and festivities, in which also intensely celebrated in Graciosa and Terceira, where people of all The volcanic phenomena that have always affected the Azores led and Cultural Information Centre of Corvo Island, which is located in the brass bands and folk dance groups are a mandatory presence. ages dress, sing and dance vividly. the population to find shelter in religiousness and to search for divine village’s historic centre and which displays information on the way of Azorean festivities and festivals are essentially characterised by lively On Terceira Island, in particular, there are some typical dances, called protection. -

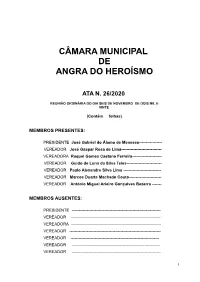

Ata N.º 26/2020, De 6 De Novembro

CÂMARA MUNICIPAL DE ANGRA DO HEROÍSMO ATA N. 26/2020 REUNIÃO ORDINÁRIA DO DIA SEIS DE NOVEMBRO DE DOIS MIL E VINTE (Contém folhas) MEMBROS PRESENTES: PRESIDENTE José Gabriel do Álamo de Meneses----------------- VEREADOR José Gaspar Rosa de Lima------------------------------ VEREADORA Raquel Gomes Caetano Ferreira---------------------- VEREADOR Guido de Luna da Silva Teles-------------------------- VEREADOR Paulo Alexandre Silva Lima ---------------------------- VEREADOR Marcos Duarte Machado Couto------------------------ VEREADOR António Miguel Arieiro Gonçalves Bezerra ------- MEMBROS AUSENTES: PRESIDENTE ------------------------------------------------------------------ VEREADOR ------------------------------------------------------------------- VEREADORA ------------------------------------------------------------------- VEREADOR -------------------------------------------------------------------- VEREADOR ------------------------------------------------------------------ VEREADOR ------------------------------------------------------------------ VEREADOR ------------------------------------------------------------------ 1 No dia seis de novembro de dois mil e vinte realizou-se na Sala de Sessões do edifício dos Paços do Concelho a reunião ordinária da Câmara Municipal de Angra do Heroísmo.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Pelas 09:45 horas, o Presidente da Câmara Municipal declarou aberta a reunião.----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Terceira - Portugal

465000 470000 475000 480000 485000 490000 495000 27°20'0"W 27°15'0"W 27°10'0"W 27°5'0"W 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 3 Activa tion ID: EMS N-018 4 4 Glide Number: (N/A) P roduct N.: 05TER CEIR A, v1, English Terceira - Portugal N Lava Flow Risk Assessment - 2015 " N 0 " ' 0 0 ' 5 0 ° Population at Risk Map - Overview 5 8 ° 3 8 3 P roduction da te: 7/1/2016 5000 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 5 9 9 2 2 4 4 100 65 76 Biscoitos 187 Altares 89 72 Raminho Cartographic Information 246 249 243 259 Vila Nova 50 159 293 2 71 Full color A1, high resolution (300dpi) 0 1:50.000 5 2 284 171 0 0,5 1 2 3 4 251 K m 50 254 373 Grid: W GS 1984 Z one 26 N ma p coordina te system Tick ma rks: W GS 84 geogra phica l coordina te system 453 Agualva ± 403 265 321 461 473 62 Legend 153 472 435 Risk Level Eruption Zone Administrative boundaries Transportation Points of Interest 501 Null Hazard 544 Sao Bras Municipa lity I4 Airport IC Hospita l 522 No V ery Low Populated places Fire sta tion 633 703 103 V ery Low Low P ort ×Ñ !. City Jc 576 640 Medium a P olice Low Bridge & overpa ss ¬ 561 663 600 !. Town 0 0 Medium High ! H Educa tion 0 0 I 1 V illa ge Tunnel 2 0 0 0 V ery High 517 726 0 0 High S ports 0 0 !(S 363 5 0 Highwa y 9 532 5 9 Buildings 00 0 V ery High 2 399 5 791 2 G Government 4 62 4 First Aid Areas P rima ry R oa d (! Fa cilities 758 7 Airport 513 685 829 5 0 512 0 1 S econda ry R oa d 5 8 599 0 First Aid Area s Úð Industria l fa cilities 7 0 0 P ort 0 Terceira Airport 786 718 760 Loca l R oa d t N 9Æ Ca mp loca tion Commercia l, P ublic & " W a ter infra structure " 847 -

THE SOLAR BRANCO ECO ESTATE GUIDE to TECERIA Last Updated Winter 2020

THE SOLAR BRANCO ECO ESTATE GUIDE TO TECERIA Last Updated Winter 2020 #WELOVEAZORES #WELOVEAZORES #WELOVEAZORES: THE #WELOVEAZORES campaign and website was created in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis. Tourism is the key driver of employment in the Azores and the impact cannot be understated on the islands. This guide aims to highlight the best local restaurants, experiences and activities on each island. Helping the recovery through sustainable tourism. Instagram: @solarbranco Facebook: Solar Branco Eco-Estate Web: weloveazores.com ABOUT THE SOLAR BRANCO ECO- ESTATE ABOUT THE PROPERTY: Solar Branco or The White Mansion in English, is located just above the historical town of Livramento on the biggest island of the Azores, Sao Miguel. The estate has 9 individual accommodation units. The main building originates from the 1800s. OUR UNIQUE EXPERIENCES: From vegan cozido to a gin tasting masterclass we have Azorean themed experiences for you to enjoy. Check these out by visiting our website here. SOCIAL MEDIA: Please feel free to check us out and follow on the following channels: Instagram: @solarbranco Facebook: Solar Branco Eco-Estate Web: solarbranco.com TERCERIA (THE PURPLE ISLAND) Soft blue and purple hydrangeas grow all over the Azores but Terceira, the third largest of the nine islands, is specifically recognized for the soft pastel color of its flowers including lilacs – hence The purple Island. One of the more beautiful gardens in the Azores is believed to be the Duke of Terceira Garden in Terceira’s capital Angra do Heroísmo (once the capital of the entire archipelago). WHAT TO SEE & DO Biscoitos Wine Museum Located conveniently in Algar do Carvão is an ancient lava tube located in Miradouro do Facho If the weather is right, this the town of Biscoitos, is a family-run wine cellar the geographic centre of the island. -

14 De Abril De 1961 II SÉRIE – NÚMERO 89 Direção-Geral Dos

14 de Abril de 1961 II SÉRIE – NÚMERO 89 Direção-Geral dos Serviços Florestais e Aquícolas Foram reconhecidos como próprios para a execução do Plano de povoamento florestal do distrito de Angra do Heroísmo os baldios municipais da ilha Terceira, com uma área de cerca de 7950 ha. Cumpridas as formalidades prescritas nas bases II, V, VII, IX e XI da Lei n.º 1971, de 15 de Junho de 1938; Atendendo ao parecer favorável do Concelho Técnico dos Serviços Florestais; Usando da faculdade conferida pelo n.º 3.º do artigo 109.º da Constituição, o Governo decreta e eu promulgo, o seguinte: Artigo 1.º São submetidos ao regime florestal parcial, por utilidade pública, os terrenos baldios situados nas freguesias de Altares, Doze Ribeiras, Feteira, Nossa Senhora do Pilar, Porto Judeu, Raminho, Ribeirinha, Santa Bárbara, S. Bartolomeu, S. Bento, S. Mateus da Calheta, S. Sebastião, Serreta e Terra Chã, do concelho de Angra do Heroísmo, e freguesias de Agualva, Biscoitos, Cabo da Praia, Fonte do Bastardo, Fontinhas, Lajes, Quatro Ribeiras, S. Brás, Praia da Vitória (Santa Cruz) e Vila Nova, do concelho de Vila da Praia da Vitória, do distrito de Angra do Heroísmo. Art.º 2.º A arborização e exploração destes baldios efetuar-se-á por conta do Estado e a partilha dos lucros líquidos, entre este e as respetivas câmaras municipais, será feita proporcionalmente às despesas custeadas pelo Estado e ao valor médio atribuído ao terreno, que foi arbitrado em 4500$ por hectare. Art.º 3.º Serão concedidos aos povos limítrofes, sem prejuízo dos trabalhos de arborização -

Transportes Nos Açores

1 Biscoitos - Serreta - Angra Domingo Partida de Angra Av. Allvaro Martins Homem 12:00 16:00 19:00 Jardim Duque da Terceira 12:05 16:05 19:05 Alto das Covas 12:06 16:06 19:06 Portoes de S. Pedro 12:07 16:07 19:07 Pesqueiro 12:21 16:21 19:21 Cruz das CInco 12:25 16:25 19:25 Cinco Ribeiras 12:28 16:28 19:28 Santa Barbara 12:33 16:33 19:33 Doze Ribeiras 12:43 16:43 19:43 Serreta 12:53 16:53 19:53 Serreta (Estalagem) 12:58 16:58 19:58 Raminho 13:08 17:08 20:08 Altares - Igreja 13:15 17:15 20:15 Biscoitos 13:25 17:25 20:25 Domingo Partida dos Biscoitos Biscoitos 10:30 13:30 Altares - Igreja 10:40 13:40 Raminho 10:47 13:47 Serreta (Estalagem) 10:58 13:58 Serreta 11:03 14:03 Doze Ribeiras 11:13 14:13 Santa Barbara 11:23 14:23 Cinco Ribeiras 11:28 14:28 Cruz das Cinco 11:30 14:30 Pesqueiro 11:35 14:35 Praca Velha - Inter-Urbanas 11:50 14:50 Guarita 11:51 14:51 Av. Allvaro Martins Homem 11:55 14:55 Segunda a Sexta Partida de Angra Av. Allvaro Martins Homem 10:30 13:00 16:00 17:00 18:00 19:00 Jardim Duque da Terceira 10:35 13:05 16:05 17:05 18:05 19:05 Alto das Covas 10:36 13:06 16:06 17:06 18:06 19:06 Portoes de S. -

INSTITUTO Hl STCRICO Da Llh a Terceira BOLETIM Histórico-DA

INSTITUTO Hl STCRICO da llh a Terceira BOLETIM HISTóRICO-DA o r-í / N.0 6 1948 BOLETIM D O INSIITUÍD IISTÓiO DA ILDA TERCEIRA Vol. VI 1948 Nola e documentos sobre o comércio de La Rocbelle com a Teiceira no século XVII Pelo Dr. JULIÃO SOARES DE AZEVEDO Já noutra ocasião procurei coligir alguns elementos para a histó- ria do comércio francês nos Açores, durante o século XVII (') Êste comércio, que não se sabe ainda em que época foi mais im- portante, estava, no entanto, no início do século XV1I1, em franca de- cadência. É pelo menos êste o parecer de Savary (2). As cidades de La Rochelle, Nantes e Marselha que, segundo êste autor, mandavam nos tempos atrás, grande quantidade de navios às Ilhas, passaram a enviá-los a outras terras. Desde o restabelecimento da paz entre Por- tugal e a França pelo Tratado de Utrecht (1715) até à data em que escrevia Savary (17171, apenas teriam vindo aos Açores 4 ou 5 em- barcações francesas. A decadência proviria da instalação, em S. Mi- guel, de indústrias de tecidos e chapéus que, utilizando mão de obra francesa, passaram a fazer concorrência, com vantagem de preço, às mercadorias do mesmo género com que a França abastecia os mer- cados açoreanos. Alguma seda francesa que aparecia era importada de Lisboa. Além de outros, não indicados por Savary, há um factor desta decadência que convém mencionar. (i) «Revista Portuguesa de História», tomo III. P) «Dictionnaire Universel de Commerce", Paris, 1732, pág. 1086 ~ 87. 2 BOLETIM DO INSTITUTO HISTÓRICO dOCU, entos adea . -

Alojamento Local Terceira

Alojamento Local N.º de Estabelecimentos 380 SECRETARIA REGIONAL DA ENERGIA, AMBIENTE E TURISMO Quartos 53 108 237 Moradia 205 530 1 172 Terceira Apartamento 97 173 401 E. Hospedagem 19 95 228 Hostel 9 75 241 Total ilha Terceira 383 981 2 279 Última Atualização: 20/08/2020 Quartos e/ou U.A. Camas RRAL PROPRIETÁRIO Dormitórios Tipo ENDEREÇO FREGUESIA TELEFONE E-mail/Website Angra do Heroísmo Desterro nº 65-67, Conceição, 9700 Angra do 1 445 Adalberto Augusto Ourique Ribeiro - "Desterro House" 1 3 5 Moradia Nª Srª da Conceição 966 584 828 [email protected] Heroísmo Estrada Regional, nº 14, Lugar do Negrito, Adalberto Manuel Rocha Alves Pinheiro - "Vivenda da Saudade 295.643.105 [email protected] 228 1 5 15 E. Hospedagem Chanoca, S. Mateus da Calheta, 9700-554 Angra São Mateus Bed & Breakfast" 914.595.229 www.vivendadasaudade.com do Heroísmo Bicas de Cabo Verde, nº23, São Pedro, 9700 1 587 Adília Maria Coelho Parreira - " Lost in Terceira" 1 2 6 Moradia São Pedro 965 359 155 [email protected] Angra do Heroísmo Quinta da Francesa, nº 51, Terra Chã, 9700-720 2 063 Alcateias Citadinas, Lda. - "Alcateias Citadinas, Lda. (Vila 51)" 1 5 10 Moradia Terra Chã 912 552 375 [email protected] Angra do Heroísmo Caminho do Meio nº94, Cave, São Pedro, 9700 1 642 Alex Bettencourt Silva Lourenço - " Excelent & Efficiency" 1 1 2 Apartamento São Pedro 963 603 993 [email protected] Angra do Heroísmo Caminho do Meio nº94, Fração I, São Pedro, 1 579 Alex Bettencourt Silva Lourenço - "Varandas de São Carlos" 1 1 3 Apartamento -

Ilha Terceira

Síntese – ilha Terceira No ano 2013, a ilha Terceira ficou marcada pelos avultados estragos resultantes das chuvadas ocorridas no mês de março. Grande parte dos estragos verificados resultaram de situações de ocupação e alteração de leitos e margens, as quais causaram estragos em bens e infraestruturas instalados no leito (ocupações), bem como em outros locais adjacentes (galgamentos e inundação, por alterações da drenagem). Várias bacias hidrográficas na ilha terceira são caracterizadas por vales pouco profundos, pelo que a rede de drenagem natural pode não ser evidente, pelo que pode ser frequentemente ocupada e interrompida perante a ausência de leito definido, sendo que os efeitos apenas se verificam posteriormente em situações de precipitação intensa. São identificadas situações de secções insuficientes de passagens hidráulicas e de encaminhamento de sistemas de drenagem de águas pluviais para locais sem capacidade de receção daqueles caudais. Várias das situações que envolvem empreitadas encontram-se já em curso, em diferentes fases de preparação e/ou execução, com responsabilidades repartidas entre várias entidades. Secretaria Regional dos Recursos Naturais Direção Regional do Ambiente Terceira | 1 Angra do Heroísmo Bacia Tipo de ocorrência Formulário Local (Ribeira/Freguesia) Prioridade Hidrográfica Ação(ões) proposta(s) 2013/131 Rib Francisco Vieira TEA3 Inundação Urgente Raminho Empreitada de requalificação do curso de água 2013/132 Ribeira de São Bento TEB32 Inundação; Obras em leitos e margens Urgente São Bento Empreitada