Bluegrass Vocals by Fred Bartenstein (Unpublished, 4.27.10) All Rights Reserved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

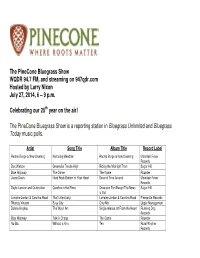

The Pinecone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and Streaming on 947Qdr.Com Hosted by Larry Nixon July 27, 2014, 6 – 9 P.M

The PineCone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and streaming on 947qdr.com Hosted by Larry Nixon July 27, 2014, 6 – 9 p.m. Celebrating our 25 th year on the air! The PineCone Bluegrass Show is a reporting station in Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Today music polls. Artist Song Title Album Title Record Label Rachel Burge & New Dawning Kentucky Mandolin Rachel Burge & New Dawning Mountain Fever Records Doc Watson Greenville Trestle High Riding the Midnight Train Sugar Hill Blue Highway The Game The Game Rounder Jason Davis Hard Rock Bottom of Your Heart Second Time Around Mountain Fever Records Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver Carolina in the Pines Once and For Always/The News Sugar Hill is Out Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road That’s Kentucky Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road Pinecastle Records Rhonda Vincent Busy City Only Me Upper Management Donna Hughes The Way I Am Single release off From the Heart Running Dog Records Blue Highway Talk is Cheap The Game Rounder Nu-Blu Without a Kiss Ten Rural Rhythm Records Kruger Brothers Streamlined Cannonball Remembering Doc Watson Double Time Music The Seldom Scene With Body and Soul The Best of The Seldom Scene Rebel Records Darrell Webb Band Folks Like Us Dream Big Mountain Fever Records Seldom Scene Wait a Minute (feat. John Starling) Long Time… Seldom Scene Smithsonian/Folkwa ys Becky Buller Southern Flavor ’Tween Earth & Sky Dark Shadow Recording Sideline Girl at the Crossroads Bar Session I Mountain Fever Records Dolly Parton Blue Smoke Blue Smoke Sony Masterworks The Gentlemen of Bluegrass Carolina Memories Carolina Memories Pinecastle Records Richard Bennett Wayfaring Stranger (feat. -

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview

2014 Joe Val Bluegrass Festival Preview The 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival is quickly approaching, February 14 -16 at the Sheraton Framingham Hotel, in Framingham, MA. The event, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, is one of the premier roots music festivals in the Northeast. The festival site is minutes west of Boston, just off of the Mass Pike, and convenient to travelers from throughout the region. This award winning and family friendly festival features three days of top national performers across two stages, over sixty workshops and education programs, and around the clock activities. Among the many artists on tap are The Gibson Brothers, Blue Highway, Junior Sisk, IIIrd Tyme Out, Sister Sadie featuring Dale Ann Bradley, and a special reunion performance by The Desert Rose Band. This locally produced and internationally recognized bluegrass festival, produced by the Boston Bluegrass Union, was honored in 2006 when the International Bluegrass Music Association named it "Event of the Year." In May 2012, the festival was listed by USATODAY as one of Ten Great Places to Go to Bluegrass Festivals Single day and weekend tickets are on sale now and we strongly suggest purchasing tickets in advance. Patrons will save time at the festival and guarantee themselves a ticket. Hotel rooms at the Sheraton are sold out, but overnight lodging is still available and just minutes away, at the Doubletree by Hilton, in Westborough, MA. Details on the festival, including bands, schedules, hotel information, and online ticket purchase at www.bbu.org And visit the 29th Joe Val Bluegrass Festival on Facebook for late breaking festival news. -

Bluegrass Outlet Banjo Tab List Sale

ORDER FORM BANJO TAB LIST BLUEGRASS OUTLET Order Song Title Artist Notes Recorded Source Price Dixieland For Me Aaron McDaris 1st Break Larry Stephenson "Clinch Mountain Mystery" $2 I've Lived A Lot In My Time Aaron McDaris Break Larry Stephenson "Life Stories" $2 Looking For The Light Aaron McDaris Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 My Home Is Across The Blueridge Mtns Aaron McDaris 1st Break Mashville Brigade $2 My Home Is Across The Blueridge Mtns Aaron McDaris 2nd Break Mashville Brigade $2 Over Yonder In The Graveyard Aaron McDaris 1st Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Over Yonder In The Graveyard Aaron McDaris 2nd Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Philadelphia Lawyer Aaron McDaris 1st Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 When My Blue Moon Turns To Gold Again Aaron McDaris Intro & B/U 1st verse Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Leaving Adam Poindexter 1st Break James King Band "You Tube" $2 Chatanoga Dog Alan Munde Break C-tuning Jimmy Martin "I'd Like To Be 16 Again" $2 Old Timey Risin' Damp Alan O'Bryant Break Nashville Bluegrass Band "Idle Time" $4 Will You Be Leaving Alison Brown 1st Break Alison Kraus "I've Got That Old Feeling" $2 In The Gravel Yard Barry Abernathy Break Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver "Never Walk Away" $2 Cold On The Shoulder Bela Fleck Break Tony Rice "Cold On The Shoulder" $2 Pain In My Heart Bela Fleck 1st Break Live Show Rockygrass Colorado 2012 $2 Pain In My Heart Bela Fleck 2nd Break Live Show Rockygrass Colorado 2012 $2 The Likes Of Me Bela Fleck Break Tony Rice "Cold On -

Songwriter Mike O'reilly

Interviews with: Melissa Sherman Lynn Russwurm Mike O’Reilly, Are You A Bluegrass Songwriter? Volume 8 Issue 3 July 2014 www.bluegrasscanada.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS BMAC EXECUTIVE President’s Message 1 President Denis 705-776-7754 Chadbourn Editor’s Message 2 Vice Dave Porter 613-721-0535 Canadian Songwriters/US Bands 3 President Interview with Lynn Russworm 13 Secretary Leann Music on the East Coast by Jerry Murphy 16 Chadbourn Ode To Bill Monroe 17 Treasurer Rolly Aucoin 905-635-1818 Open Mike 18 Interview with Mike O’Reilly 19 Interview with Melissa Sherman 21 Songwriting Rant 24 Music “Biz” by Gary Hubbard 25 DIRECTORS Political Correctness Rant - Bob Cherry 26 R.I.P. John Renne 27 Elaine Bouchard (MOBS) Organizational Member Listing 29 Gord Devries 519-668-0418 Advertising Rates 30 Murray Hale 705-472-2217 Mike Kirley 519-613-4975 Sue Malcom 604-215-276 Wilson Moore 902-667-9629 Jerry Murphy 902-883-7189 Advertising Manager: BMAC has an immediate requirement for a volunteer to help us to contact and present advertising op- portunities to potential clients. The job would entail approximately 5 hours per month and would consist of compiling a list of potential clients from among the bluegrass community, such as event-producers, bluegrass businesses, music stores, radio stations, bluegrass bands, music manufacturers and other interested parties. You would then set up a systematic and organized methodology for making contact and presenting the BMAC program. Please contact Mike Kirley or Gord Devries if you are interested in becoming part of the team. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Call us or visit our website Martha white brand is due to the www.bluegrassmusic.ca. -

Voices in the Hall: Sam Bush (Part 1) Episode Transcript

VOICES IN THE HALL: SAM BUSH (PART 1) EPISODE TRANSCRIPT PETER COOPER Welcome to Voices in the Hall, presented by the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. I’m Peter Cooper. Today’s guest is a pioneer of New-grass music, Sam Bush. SAM BUSH When I first started playing, my dad had these fiddle albums. And I loved to listen to them. And then realized that one of the things I liked about them was the sound of the fiddle and the mandolin playing in unison together. And that’s when it occurred to me that I was trying on the mandolin to note it like a fiddle player notes. Then I discovered Bluegrass and the great players like Bill Monroe of course. You can specifically trace Bluegrass music to the origins. That it was started by Bill Monroe after he and his brother had a duet of mandolin and guitar for so many years, the Monroe Brothers. And then when he started his band, we're just fortunate that he was from the state of Kentucky, the Bluegrass State. And that's why they called them The Bluegrass Boys. And lo and behold we got Bluegrass music out of it. PETER COOPER It’s Voices in the Hall, with Sam Bush. “Callin’ Baton Rouge” – New Grass Revival (Best Of / Capitol) PETER COOPER “Callin’ Baton Rouge," by the New Grass Revival. That song was a prime influence on Garth Brooks, who later recorded it. Now, New Grass Revival’s founding member, Sam Bush, is a mandolin revolutionary whose virtuosity and broad- minded approach to music has changed a bunch of things for the better. -

BLUEGRASS SIGNAL #246: Short Life of Trouble – Grayson & Whitter, Part 1 Broadcast Dates: Feb

BLUEGRASS SIGNAL #246: Short Life Of Trouble – Grayson & Whitter, part 1 Broadcast dates: Feb. 14-19, 2020 GRAYSON & WHITTER: Train Forty Five/The Recordings of Grayson & Whitter (County/27) DOC WATSON AND CLARENCE ASHLEY: Old Ruben/Original Folkways Recordings (Smithsonian-Folkways/61) J.D. CROWE & THE KENTUCKY MOUNTAIN BOYS: Train 45/Bluegrass Holiday (Rebel/69) GRAYSON & WHITTER: The Nine Pound Hammer/Ommie Wise (Suncoast/28) MONROE BROTHERS: Nine Pound Hammer Is Too Heavy/Blue Moon Of Kentucky (Bear Family/36) VERN WILLIAMS BAND: Roll On Buddy/Traditional Bluegrass (Arhoolie/82) GRAYSON & WHITTER: Short Life Of Trouble/The Recordings of Grayson & Whitter (County/27) DAVE EVANS & THE RIVER BEND: Short Life Of Trouble/The Best Of the Vetco Years (Rebel/79) DUDLEY CONNELL & DON RIGSBY: Short Life Of Trouble/Meet Me By The Moonlight (Sugar Hill/00) GRAYSON & WHITTER: Little Maggie With a Dram Glass in Her Hand/Ommie Wise (Suncoast/28) RALPH STANLEY & THE CLINCH MOUNTAIN BOYS: Little Maggie/Live In Japan (Rebel/71) BARBARA DANE with TOM PALEY: Little Maggie/When I Was A Young Girl (Horizon/62) GRAYSON & WHITTER: A Dark Road Is A Hard Road To Travel/The Recordings of Grayson & Whitter (County/28) RALPH STANLEY: A Dark Road Is A Hard Road To Travel/Short Life Of Trouble - Songs Of Grayson and Whitter (Rebel/96) GRAYSON & WHITTER: Going Down the Lee Highway/The Recordings of Grayson & Whitter (County/28) LEE HIGHWAY: Lee Highway Blues/Bluegrass Music (self/07) <><><><><><><><><><> BLUEGRASS SIGNAL #247: Down In the Willow Garden – Grayson -

282 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER #282 COUNTY SALES P.O. Box 191 November-December 2006 Floyd,VA 24091 www.countysales.com PHONE ORDERS: (540) 745-2001 FAX ORDERS: (540) 745-2008 WELCOME TO OUR COMBINED CHRISTMAS CATALOG & NEWSLETTER #282 Once again this holiday season we are combining our last Newsletter of the year with our Christmas catalog of gift sugges- tions. There are many wonderful items in the realm of BOOKs, VIDEOS and BOXED SETS that will make wonderful gifts for family members & friends who love this music. Gift suggestions start on page 10—there are some Christmas CDs and many recent DVDs that are new to our catalog this year. JOSH GRAVES We are saddened to report the death of the great dobro player, Burkett Graves (also known as “Buck” ROU-0575 RHONDA VINCENT “Beautiful Graves and even more as “Uncle Josh”) who passed away Star—A Christmas Collection” This is the year’s on Sept. 30. Though he played for other groups like Wilma only new Bluegrass Christmas album that we are Lee & Stoney Cooper and Mac Wiseman, Graves was best aware of—but it’s a beauty that should please most known for his work with Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs, add- Bluegrass fans and all ing his dobro to their already exceptional sound at the height Rhonda Vincent fans. of their popularity. The first to really make the dobro a solo Rhonda has picked out a instrument, Graves had a profound influence on Mike typical program of mostly standards (JINGLE Auldridge and Jerry Douglas and the legions of others who BELLS, AWAY IN A have since made the instrument a staple of many Bluegrass MANGER, LET IT bands everywhere. -

The Fiddler Magazine General Store NEW! Vintage Fiddler Photo Note Cards! Six Credit Card Payments Are Only Accepted Through Paypal (Order Online At

The Fiddler Magazine General Store NEW! Vintage fiddler photo note cards! Six Credit card payments are only accepted through PayPal (order online at www.fiddle.com). cards (one each of six Special Offers: • Bonus with 3-year subscriptions: Get a free back issue of your choice! designs), with env. $5. • Any 10 back issues: $40; ALL available back issues: $150 (over a $250 value!). • BACK ISSUE SALE: Selected back issues are on sale. BACK ISSUES (Only avail. issues are listed below. Quantities limited.) Spring ’94: Martin Hayes; County Clare Fiddling; Laurie Lewis… Fall ’95: Donegal Fiddling; Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh; Canray Fontenot; Oliver Schroer; “Cindy” Lyrics; Fiddling in the 1700s; Fiddling Bob Taylor… Fall ’05: Johnny Frigo; Day of the Dead; Wendy MacIsaac; Stephan Dudash; Ned Win. ’96/’97: Blues; Vassar Clements; Paul Anastasio; Bulgarian; Bob McQuillen… Steinberger; Robert Burns & Scots Fiddling; Graded Fiddle Tunes… Summer 97: Kentucky Fiddling; Bruce Greene; Stuart Duncan; Pierre Schryer; Winter ’05/’06: Cajun Fiddling; Dirk Powell; David Greely; Festivals Acadiens; Cowboy Fiddler Woody Paul… Ranchdance Fiddlers; Robert Wilson: One-String Fiddler; The Caledonian Pocket Win. ’97/’98: NY State Fiddling; Jay Ungar; James Kelly; Björn Ståbi; Alan Lomax… Companion; A “Winning” Contest Round, Part One… Summer ’98: Texas Fiddling special; Frankie McWhorter; Dick Barrett; Orville Summer ’06: Donegal’s Caoimhin Mac Aoidh; James O’Neill; Alan Jabbour; Burns; Jimmie Don & Valerie Bates; Lanny Fiel; Orkney’s Wrigley Twins… Hungarian Gypsy Fiddling; Hunter Berry; A “Winning” Contest Round II… Fall ’98: Mexican Fiddling; Juan Reynoso; Mariachi Queen Laura Sobrino; Fall ’06: Jake Krack; Eastern European Fiddling; Washington’s Floyd Engstrom; Nashville’s Buddy Spicher; Mark O’Connor; George Wilson… Fiddling in Jämtland, Sweden; A “Winning” Contest Round III… Winter ’98/’99: Randal Bays; Jean-Luc Ponty; J.P. -

B Uegrass Canada I

BUEGRASS CANADA I The official magazine of the Bluegrass Music Association of Canada www.bluegrasscanada.ca SELDOM SCENE 2012 1976 VOLUME 6 ISSUE 3 AUGUST 2012 WHAT"S INSIDE President Secretary Denis Chadbourn Leann Chadbourn Editor's Message-Pg 2 705-776-7754 705-776-7754 President's Message-Pg 3 Vice-president Treasurer Tips for Bands-Pg 4 Dave Porter Roland Aucoin The Western Perspective-Pg 6 905-635-1818 Feature Article-SELDOM SCENE-Pgs. 7-9 Q & A's With Steep Canyon Rangers-Pgs. 10-13 Maritime Notes Pg. 16 Providence Bay 2012 Pg-18 Directors at Large Advertising Rates Pg 19 Gord deVries Murray Hale 705-4 7 4-2217 Organizational Memberships -Pgs. 20 & 21 519-668-0418 Donald Tarte Tasha Heart-Social Media Just A Bluegrass Wife-Pgs. 23-26 877 -876-3369 Wilson Moore Congratulations to Spinney Brothers-Pg 26 Bill Blance Jerry Murphy, Region 1 SPECIAL NOTICE-Pg. 27 Representative 905-451-9077 Tim's CD Reviews-(Unavailable for this publication) Rick Ford- Region 4 Music Biz Article (Unavailable for this publication) Representative Advertising Pages-various pages Editor's Message - Any bands wishing to have this information included must provide itto me before September 15th, 2012. The Leann Chadbourn email address to send it to is at the bottom of this page We have some great articles in this issue with our trusty and on the Notice. writers, Gord DeVries, Denis Chadbourn, Diana van Holten, Wilson Moore & Darcy Whiteside. Since it's vacation time I Again, BMAC welcomes any interesting articles or infor took it seriously, and didn't get out reminders to everyone for mation relevant to Bluegrass and are hopeful to start receiv our deadline dates so we will be missing our Music Biz Arti ing articles from Coast to Coast. -

Reno-Style Workshop

that followed. And Earl Scruggs set the RENO-STYLE standard for bluegrass banjo playing on those historic Columbia recordings. This was also the band in which Lester Flatt WORKSHOP and Earl Scruggs first became acquainted and would later form the most popular bluegrass band in history. To say this was Reno Roots Part 3—The Decision an historic time is an understatement. So the question is, “What if Don took Jason Skinner the job instead of joining the army?” In 1943 a monumental event took place history. Well it’s hard to say because it would that would not only change Don Reno’s Why was this event so important? have affected so many things, especially life but the evolution of the 5-string banjo, Because his decision affected everything musical associations. The most obviously and bluegrass music forever. It was May that was to follow. When Don turned affected would have been the associations 17, 1943 that Don Reno decided to turn down the job as the first three-finger between Flatt and Scruggs and Reno and down an offer from Bill Monroe to join style banjo player for Bill Monroe, the Smiley. These legendary bands may not the Bluegrass Boys, so that he could join job went to none other than Earl Scruggs have existed if Don took the job with the US Army instead. At the time, Don’s in 1945. With the addition of this “new” Monroe. In fact we may have even have decision probably didn’t seem like such a style of banjo playing, the Bluegrass Boys ended up with Flatt and Reno instead of big deal, but looking back it was one of the exploded in popularity. -

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and Their Fans

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Annie Lyons TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin December 2020 __________________________________________ Renita Coleman Department of Journalism Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Hannah Lewis Department of Musicology Second Reader 2 ABSTRACT Author: Annie Lyons Title: One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Supervising Professors: Renita Coleman, Ph.D. Hannah Lewis, Ph.D. Boy bands have long been disparaged in music journalism settings, largely in part to their close association with hordes of screaming teenage and prepubescent girls. As rock journalism evolved in the 1960s and 1970s, so did two dismissive and misogynistic stereotypes about female fans: groupies and teenyboppers (Coates, 2003). While groupies were scorned in rock circles for their perceived hypersexuality, teenyboppers, who we can consider an umbrella term including boy band fanbases, were defined by a lack of sexuality and viewed as shallow, immature and prone to hysteria, and ridiculed as hall markers of bad taste, despite being driving forces in commercial markets (Ewens, 2020; Sherman, 2020). Similarly, boy bands have been disdained for their perceived femininity and viewed as inauthentic compared to “real” artists— namely, hypermasculine male rock artists. While the boy band genre has evolved and experienced different eras, depictions of both the bands and their fans have stagnated in media, relying on these old stereotypes (Duffett, 2012). This paper aimed to investigate to what extent modern boy bands are portrayed differently from non-boy bands in music journalism through a quantitative content analysis coding articles for certain tropes and themes. -

Peter Rowan Bluegrass Band

Peter Rowan Bluegrass Band The Peter Rowan Bluegrass Band consists of outstanding musicians with over 100 years of combined recording and performance experience. Joining guitarist Peter Rowan are Keith Little, banjo; Chris Henry, Mandolin; Paul Knight, bass; and Blaine Sprouse, fiddle. The ensemble has graced the stages of Hardly Strictly Bluegrass, Grey Fox, Merlefest, Rothbury Australia’s National Folk Festival, and numerous other festivals domestically and abroad, entertaining audiences with original and traditional songs executed in vibrant harmony. In April 2013 Peter Rowan, joined by members of his current Bluegrass Band, released The Old School, a magnificent blending of old school sounds and players (Del McCoury, Jesse McReynolds, Bobby Osborne and Buddy Picher) with some of the bright young talent such as Chris Henry, Ronnie & Robbie McCoury performing memorable new songs such as “Doc Watson Morning”, “Drop The Bone” and “Keepin’ It Between The Lines (Old School)”. The Old School followed the group’s debut album for Nashville’s Compass Records- Legacy; the recording, featuring traditional and original compositions, was produced by Compass owner/recording artist Alison Brown and includes Ricky Skaggs, Gillian Welch, David Rawlings and Del McCoury. Legacy received a Grammy nomination in 2010. Peter Rowan – Guitar, Vocals GRAMMY-award winner and six-time GRAMMY nominee, Peter Rowan is a bluegrass singer-songwriter with a career spanning over five decades. From his early years playing under the tutelage of bluegrass patriarch Bill Monroe, Peter’s stint in Old & In the Way with Jerry Garcia and his subsequent breakout as both a solo performer and bandleader, Rowan has built a devoted, international fan base through his continuous stream of original recordings, collaborative projects, and constant touring.