Herrings and the First Great Combine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alewives and Blueback Herring Juila Beaty University of Maine

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Sea Grant Publications Maine Sea Grant 2014 Fisheries Then: Alewives and Blueback Herring Juila Beaty University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/seagrant_pub Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Repository Citation Beaty, Juila, "Fisheries Then: Alewives and Blueback Herring" (2014). Maine Sea Grant Publications. 71. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/seagrant_pub/71 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Sea Grant Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (http://www.downeastfisheriestrail.org) Alewives and Blueback Herring Fisheries Then: Alewives and Blueback Herring (i.e. River Herring) By Julia Beaty and Natalie Springuel Reviewed by Chris Bartlett, Dan Kircheis The term “river herring” collectively refers to two species: Alosa pseudoharengus, commonly known as alewife, and the closely related Alosa aestivalis, commonly known as blueback herring, or simply bluebacks. Records dating back to the early nineteenth century indicate that fishermen could tell the difference between alewives and bluebacks, which look very similar; however, historically they have been harvested together with little regard to the differences between the two (Collette and KleinMacPhee 2002). Alewives are the more common of the two species in most rivers in Maine (Collette and Klien MacPhee 2002). Fishermen in Maine often use the word “alewife” to refer to both alewives and bluebacks. Both alewives and bluebacks are anadromous fish, meaning that they are born in fresh water, but spend the majority of their adult lives at sea. -

Cutting. We Started a Research Program to Investigate the Process of Curing Fish in Traditional Kilns

THE TORRY KILN ITS DESIGN AND APPLICATION WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE COLD SMOKING OF SALMON, HERRING, AND COD Alex M cK . Bannerman, M BE A. I. F . S. T. Independent Consultant Swanland, North Ferriby Yorkshire HU14 3QT En gland 44! 0482-633124 In 1933, I was privileged to join the Torry Research Station in Aberdeen, Scotland. I worked for the director, the late Dr. G. A. Reay, investigating fish proteins, freezing, cold storage, salting, and dehydration of herring and cod, and the analytical techniques to test these processes ~ In 1936 37, I became involved in smoke curing fish, working with Dr. Charles Cutting. We started a research program to investigate the process of curing fish in traditional kilns. Some of these kiln s were 800 ft square and 30 ft high. We measured air flow, temperatures, humidities, and weight loss of fish during smoking. From the data, we built a picture of the irregularities and disadvantages of smoking in these old kilns. However, this also led to improving the process. After several attempts, we developed a simple tunnel design in which fish could be smoked under controlled conditions. The process was more economical, faster, and the product more uniform. This is a bit of history, but it was from this work that we built our expertise and knowledge of fish. A previous speaker suggested that with modern, programmable smoking equipment it is only necessary to push buttons, and "witch doctors" are no longer needed. I would agr ee with this for products such as salami, sausages, and other products manufactured from uniform ingredients in skins of uniform length and thickness ~ However, fish come in all shapes and sizes, with differing fat, protein and water content. -

Studies on Smoke Curing of Tropical Fishes

Studies on smoke curing of tropical fishes Item Type article Authors Devadasan, K.; Muraleedharan, V.; Joseph, K.G. Download date 01/10/2021 23:42:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/33671 NOTE H STUDIES ON SMOKE CURING OF TROPICAL FISHES In spite of the tremendous progress prejudice among the local processors engagea made by our freezing and canning industries, in fish curing against chemical preservatives, curing still continues to be a very important it has not yet become very popular. So, method of fish preservation in our coun- as an alternative, a well known natural try. This is especially so for our internal preservative and food additive viz; turm- market, since our freezing and canning eric was tried as preservative for such industries are completley export oriented. products. This treatment is found to But surprisingly, smoke curing, a simple increase the storage life of the final smoked and efficient method, is not yet very products, besides imparting an attractive popular among our fish curers. Smoking appearance. is a favourite method of curing in the Far East and Continental countries, where a Fresh fish [mackerel (Rastrelliger veriety of smoked products like Bloater, kanagurta) cat fish (Tachisurus dussumeri) Kipper, Red herring, Buckling, pale cure and sole (Cynoglossus dubis)] were pro- Finnan, Golden cutlets, Scotch fillets, Smo- cured from local fish landing centres. kies etc. are prepared. Extensive studies They were gutted, cleaned and washed. In have also been conducted there on the the case of sole the upper hard skin was various aspects of this method of curing removed before washing. -

Atlantic Herring (Clupea Harengus) As a Case Study for Time Series Analysis and Historical Data Emily Klein University of New Hampshire, Durham

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Winter 2008 A new perspective: Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) as a case study for time series analysis and historical data Emily Klein University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Klein, Emily, "A new perspective: Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) as a case study for time series analysis and historical data" (2008). Master's Theses and Capstones. 424. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/424 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NEW PERSPECTIVE: ATLANTIC HERRING {CLUPEA HARENGUS) AS A CASE STUDY FOR TIME SERIES ANALYSIS AND HISTORICAL DATA BY EMILY KLEIN BS, University of California, San Diego, 2003 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science In Natural Resources: Environmental Conservation December 2008 UMI Number: 1463228 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Literature and Libations

Literature and Libations Y FEBRUARYor not unaware of this connec- March in Vermont, tion, and some may take Bfishing is a language advantage of it. In "Anglmg I've half forgotten. I drive past Art: The Winemaker's Label," the iced-over, snow-covered Fowler gives us a brief history river and trv to remember of the wine label, from marked ever wading in. That I even earthen jars to the paper labels own fly rods is a tough recol- we know today. Some labels are lection. In winter, it seems the created to capture the charac- sport has nothing to do with ter of the Gine, but angling me, even as I pull together a labels reflect the angling wine- fly-fishing journal. maker's passion for the sport When trout season closes and "much like an artificial fly, and the days grow shorter and are designed to induce an colder, bitG literature and angler or his or her friends to libations begin to play more buy the product." Fowler gives us examples of of a in my life than fly Timber-frame ceiling of the Museum's new gallery space. fishing. In this issue, authors wineries that have incorporat- link tGe sport to both. .. ed the fly-fishing image into While doing research for some of their wine names and one of his own projects, Robert Boyle chanced upon an oddly labels. He discusses some of the artists involved and how the familiar photo of Preston Jennings. He soon figured out that it wineries came to commission or design the label. -

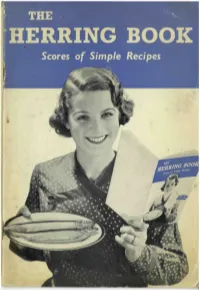

HERRING BOOK Scores of Simple Recipes

THE HERRING BOOK Scores of Simple Recipes i - ,) THE HERRING BOOK SCORES OF SIMPLE RECIPES Issued by the Herring Industry Board. CONTENTS PAGE HERRINGS FOR VALUE i By Mrs. Stanley Wrench. HERRINGS FOR HEALTH .. .. .. .. .. 2 By a Medical Man. Two WAYS TO TACKLE A HERRING WHEN COOKED 3 SIMPLEWAYSWITHFRESHHERRINGS .. .. 4 HERRINGS FOR BREAKFAST .. .. .. .. 12 HERRINGS FOR DINNER 16 HERRINGS FOR TEA .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 HERRINGS FOR SUPPER 26 HERRINGS FOR INVALIDS AND BABIES .. .. 30 HERRINGS IN VARIETY 32 INDEX .. .. ., .. .. .. Page 3 of Cover Herrings for Value by Mrs. Stanley Wrench I like good food and I enjoy cooking it—that in itself would be enough to make me enthusiastic about herrings. There is so much flavour and tastiness in these fine plump fish ; and so many interesting and delicious ways of preparing and serving them. Herrings hot, herrings cold, herrings in pies, salads and hors-d'oeuvres. Herrings for a quickly prepared strengthening breakfast, especially in the form of kippers and bloaters, which are the easiest of all to cook. A healthful lunch for school-children, or an appetising, easily- digested evening meal—I recommend them all, with all my heart. And what with fresh herrings, red herrings, kippers, bloaters, and herring roes, you can ring the changes on herring meals almost indefinitely. The recipes I have chosen for this little book will give you some idea of what can be done with herring ; and once you have discovered how popular they are, I feel sure you will work out perhaps even more successful dishes for yourself. But before we come to the actual recipes, I want to say a word or two about the wonderful value of herrings. -

Atlantic Herring (Clupea Harengus)

Emerging Species Profile Sheets Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) Common Names: Sea herring, midge herring, sardine, bloater or kipper(Smoked). Description, Distribution and Biology Atlantic herring is a pelagic (mid and upper water column) schooling fish from the family Clupeidae. It has an elongated, laterally compressed, streamline body, with a deeply forked tail and single dorsal fin. Its scales are large, loose and cover the entire body. Atlantic herring has iridescent blue-green backs, shading to silver sides on its sides and Figure 1. Atlantic herring. Source: Department of Fisheries and Oceans, abdomen, providing camouflage in the open Canada. ocean (Fig. 1). Maximum size attained for both male and female is approximately 43 cm in length and 0.68 kg. Atlantic herring is distributed throughout the Herring North Atlantic in temperate waters (1-18°C) at depths between 0 and 200 m (Fig. 2). In the 80 northeastern Atlantic it ranges from Iceland to 60 the White Sea and southward to the Strait of 40 20 Gibraltar. In the west Atlantic this species can e d u t be found from Greenland to Labrador as well i 0 t a L * Herring as Cape Hatteras, USA. Commercial -20 quantities of herring are commonly found off -40 the southern coast of Labrador, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Bay of Fundy, and in coastal -60 -150 -100 -50 0 50 100 150 and bank areas around Nova Scotia. In Longitude addition, there are five distinct stocks of herring distributed along the east and Figure 2. Atlantic Herring Distribution. -

Leaflet196.Pdf

United ,states Department of the Iilterior, J. A . Krug , Sectetar y Fish and Wildlife Service, Al b ert ,. 0 Day , Director .F ishery Lea flet 196 Washington 25, D. c. ' * Reis sued Jul y 1949 ~ :" ' SMOKING OF HERR I NG By Norman Do Jarvis Technolog ist , Br anc h of Corrune rci( 1 Fisher i e s . ' .. Contents ... ;.. f'~: ge : . Page Introduct ion • 0 0 • • • • • • • • • 1 Kippe r ed he rring . 7 Ha rd smoked herri ng . • • 0 2 Buckl i nf;' • • • 0 . 9 Red '.he'l;'r:;i..J:}g .• ' ." ' . ~ . • • • • • • • • 5 Modif ied buckling c ure . ., . ~ . 9 B loate l;' S ' : aT b l oa ~, er. .herring . 0 • • • 6 Spr at s . • • . 10 Bloaters . ~r.lgJish : ~~ thod . • . •• • • 6 . : ~ . .UlTRODUCT ION ,': .'. The ,s·ea: herring .( Cl ,upea ha rengus) W8 S pr obably the first fish to be smoked ,on e. c(;munercia l ' sc!?--le'. Ha r d..,s moked ,herring wu s one of thEl fyw f ood pr oducts in the Mi ddl e .. Ag es . which c auld be. pr e s e.rved f or more' than a short ' t 1me with a ny degree of. suc;eesso In an a ge whe,n comme rce wa s genera lly local , it found a ma rket in many parts of, Europe . As. f a r' bu ck a s the time' of Edward I, Yarmouth wa s a lready noted for' , i t s ,'smoked: he rring ; a nd Eng lish merchants we r e expor t i ng smoked herring to the c ont i nent ,. -

Historical Aspects of Fish

CHAPTER 1 Historical Aspects of Fish C. L CUTTING Humber Laboratory, Hull, England I. Early History 1 A. Prehistoric Times 1 B. Bronze Age 2 C. Classical Times 3 II. Middle Ages 6 A. General 6 B. Herring 8 C. White Fish 16 D. Consumer Aspects 19 III. Modern Era 20 A. The Rise of the Fresh Fish Trade 20 B. Fish Meal 23 C. Fried Fish Trade 23 D. Freezing 24 E. Mildly Smoked Fish 25 F. Canning 26 IV. The Future 27 References 27 The rapid perishability of fish, as compared with meat, for example, has at all times and places made preservation against putrefaction an urgent necessity. Historical aspects of the various techniques that have been evolved up to the present day have recently been discussed at some length, mainly from the British point of view (Cutting, 1955). This chap ter attempts to summarize the principal developments, giving special attention to recent contributions to the subject (Bridbury, 1955; Went- worth, 1956; Doorman, 1957; Chimits, 1957). I. Early History A. PREHISTORIC TIMES Man has always exploited for food the aqueous phase of the earth's surface. Fortunately, early men made no attempt to dispose of refuse, and we, therefore, know from kitchen middens that shellfish have been gathered from ponds, rivers, and sea coasts since the very beginning of mankind and must, in fact, have been the chief source of animal protein in the first and much the longest food-gathering stage of human history. 1 2 C. L. CUTTING The bones of fish and marine mammals, which can still be identified, testify to the advance in skill and intelligence implied by active hunting, as compared with mere collection. -

Alewives and Blueback Herring Julia Beaty University of Maine

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Sea Grant Publications Maine Sea Grant 2014 Fisheries Now: Alewives and Blueback Herring Julia Beaty University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/seagrant_pub Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Repository Citation Beaty, Julia, "Fisheries Now: Alewives and Blueback Herring" (2014). Maine Sea Grant Publications. 72. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/seagrant_pub/72 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Sea Grant Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (http://www.downeastfisheriestrail.org) Alewives and Blueback Herring Fisheries Now: alewives and blueback herring (“river herring”) By Julia Beaty Reviewed by Chris Bartlett, Claire Enterline, Dan Kircheis, and Rory Saunders Watch “Harvester perspectives on alewives, blueback herring, and American eels in Downeast Maine (http://www.seagrant.umaine.edu/oral historiesalewifeeel)” oral history video series. Alewives (Alosa pseudoharengus) and blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis), collectively referred to as river herring, are anadromous fish, which means they spend most of their adult lives at sea but spawn in freshwater. The two (http://www.downeastfisheriestrail.org/wp species look very similar. Fishermen usually harvest both species together content/uploads/2014/11/blueback_alewife_Orla and generally do not distinguish between the two. In Downeast Maine, nd_JuliaBeaty_alewives_now.png) alewives are more common than bluebacks and locals often use the terms Justin Sutherland displays a blueback herring (top) and an “alewives” to refer to both species. -

TO 1985 1 DFO Li L~Lilmlifif Lll ~L~~L Lillilillli[Jjieque 14003232

ANNEX TO THE WORLDWIDE FISHERIES MARKETING STUDY: ..---~~TS TO 1985 1 DFO li l~lilmlifIf lll ~l~~l lillilillli[JJieque 14003232 Government Gouvernement _.-...,.... of Canada du Canada SH 328 F1shenes Peches W6713 and Oceans et Oceans v. 4 Industry, Trade lndustne and Commerce et Commerce (This Report is one of a series of country and species annexes to the main study - entitled the (' 11 erview). D R A F T Annex to the Worldwide Fisheries Marketing Study: Prospects to 1985 HERRING P.M. Jangaard Department of Fisheries and Oceans October 1979 - i - ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The preparation of the Worldwide Fisheries Marketing Study, of which this Report is a part, embodies many hours of work not only by the authors but also and more importantly by those who generously provided us with market information and advice. Specifically, this Report would not have been possible without the cooperation and assistance of fishermen, processors, brokers, wholesalers, distributors, retailers, consumers and their organizations as well as government officials with whom we visited and interviewed. Though too numerous to mention separately, we would like to extend our sincere gratitude and appreciation. The views expressed in this Study, however, are ours alone and reflect the Canadian perception of worldwide markets. With regard to the overall Study, we would like to acknowledge: the encouragement of G.C. Vernon, Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) and C. Stuart, Department of Industry, Trade and Commerce (IT&C); the guidance of the Steering Committee: K. Campbell, Fisheries Cou~cil of Canada; R. Bulmer, Canadian Association of Fish Exporters; R. Merner, IT&C; and J D Puccini (and J. -

0471227161.Pdf

Chef’s Book of Formulas, Yields, and Sizes Third Edition ARNO SCHMIDT JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. Chef’s Book of Formulas, Yields, and Sizes Chef’s Book of Formulas, Yields, and Sizes Third Edition ARNO SCHMIDT JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. This book is printed on acid-free paper. \ Copyright © 2003 by Arno Schmidt. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechani- cal, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, with- out either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clear- ance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750- 8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Per- missions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the Publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no repre- sentations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials.