A Randomized Trial of Endovascular Embolization Treatment in Pelvic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argon Medical Devices Products Catalogue

ARGON PRODUCTS CATALOGUE Argon Medical Devices Products Catalogue WWW.ARGONMEDICAL.EU.COM www.argonmedical.eu.com[ 1 ] ARGON PRODUCTS CATALOGUE WWW.ARGONMEDICAL.EU.COM [ 2 ] [ 3 ] ARGON PRODUCTS CATALOGUE Table of Contents Thrombus Management .....................................................5 Endomyocardial Biopsy ................................................... 63 • Option™ELITE Inferior Vena Cava Filter System ....................6 • Jawz™ Endomyocardial Biopsy (EMB) Forceps ................... 64 • Atrieve™ Vascular Snare Kit ����������������������������������������������������8 • Endomyocardial Biopsy Accessories ���������������������������������� 65 • V+Pad™ Hemostasis Pads ......................................................9 • CLEANERXT™ & CLEANER15™ Rotational Thrombectomy System ................................................................................. 10 Bone & Bone Marrow Biopsy .......................................... 67 • T-Lok™ Bone Marrow Biopsy Needles ................................. 68 • Bone Marrow Aspiration Needles....................................... 68 Drainage ............................................................................13 • Bone Marrow Harvest Needles .......................................... 69 • SKATER™ Single Step Drainage Catheters ......................... 15 • Pediatric Bone Marrow Access Needles ............................ 69 • SKATER™ Drainage Catheters ............................................. 16 • Osty-Core™ Bone Biopsy Needles ...................................... -

Contemporary Methods for the Treatment of Pulmonary Embolism — Is It Prime-Time for Percutaneous Interventions?

Kardiologia Polska 2017; 75, 11: 1161–1170; DOI: 10.5603/KP.a2017.0125 ISSN 0022–9032 ARTYKUŁ SPECJALNY / STATE-OF-THE-ART REVIEW Contemporary methods for the treatment of pulmonary embolism — is it prime-time for percutaneous interventions? Marcin Kurzyna1, Arkadiusz Pietrasik2, Grzegorz Opolski2, Adam Torbicki1 1Department of Pulmonary Circulation, Thromboembolic Diseases and Cardiology, European Health Centre Otwock, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Otwock, Poland 2Department and Faculty of Cardiology, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland Marcin Kurzyna, MD, PhD. Since 1998 he has been a physician in the Intensive Care Unit, and since 2003 the Head of the Haemodynamic Lab in the National Institute for Lung Diseases. Cur- rently he is Deputy Head of the Department of Pulmonary Circulation, Thromboembolic Diseases, and Cardiology and an associate professor in the Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education in Warsaw. He was a Chairman of Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation of Polish Cardiac Society (2013–2015). He is a specialist in internal medicine and cardiology and has a PhD in respiratory medicine. His research interests are currently related to the role of invasive procedures in the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary vascular diseases. Arkadiusz Pietrasik, MD, PhD is an assistant in the First Chair and Department of Cardiology, Medical University of Warsaw. He is an independent operator certified by the Association of Car- diovascular Interventions (AISN) of the Polish Cardiac Society. His research interests cover structural heart diseases, coronary artery diseases, intravascular visualisation techniques, and chronic throm- boembolic pulmonary hypertension. He is a coordinator of the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (CELZAT) at the Central Clinical Hospital of the Medical University of Warsaw. -

Stock Available with Stock Position

scode generic measurement Formulation Stock Available [Customer Demand Annualy] Annual Consumption A003 ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID 300MG TABLET 3,170 12,240 4,177 A017 ANTACID CHEWABLE TABLETS TABLET CHEWABLE 221,950 646,560 386,286 A022 BACLOFEN 10MG TABLET 64,848 483,732 319,924 A038 CALCIUM LACTATE 300MG TABLET 266,000 1,797,612 1,172,351 A042 CARBIDOPA|LEVODOPA 10MG|100MG TABLET 145,200 1,661,940 1,560,315 A043 CARBIDOPA|LEVODOPA 25MG|250MG TABLET 2,850 A062 CLOMIPRAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE 25MG TABLET 320,000 1,731,612 976,556 A063 COLCHICINE 500µ TABLET 49,254 314,412 171,971 A073 DAPSONE 50MG TABLET 13,552 22,668 12,395 A077 DIGOXIN 0.0625MG TABLET 313,936 1,313,736 827,752 A089 DYDROGESTERONE 10MG TABLET 2,520 7,128 2,234 A094 ETHAMBUTOL HYDROCHLORIDE 400MG TABLET 3,864 15,012 9,882 A112 FRUSEMIDE 40MG TABLET 175,700 872,880 479,257 A113 FUSIDATE SODIUM 250MG TABLET 2,300 9,888 5,318 A115 GLYCERYL TRINITRATE 500µ TABLET 36,340 578,364 324,289 A119 HALOPERIDOL 0.5MG CAPSULE 49,448 363,552 429,849 A137 ISOSORBIDE DINITRATE 10MG TABLET 338,080 1,005,972 386,600 A149 LOPERAMIDE HYDROCHLORIDE 2MG CAPSULE 19,900 229,284 116,993 A154 MEDROXYPROGESTERONE ACETATE 5MG TABLET 1,000 5,592 3,626 A155 MEDROXYPROGESTERONE ACETATE 100MG TABLET 4,200 24,456 13,295 A172 MEXILETINE HCL 200MG CAPSULES 1,680 2,296 A176 METOCLOPRAMIDE 10MG TABLET 59,892 167,208 72,894 A179 NAPROXEN 250MG TABLET 56,636 158,316 26,261 A184 NITROFURANTOIN 50MG CAPSULE 11,220 77,112 37,419 A188 OESTROGENS CONJUGATED 0.625MG TABLET 1,764 9,696 7,716 A202 PHENOXYMETHYLPENICILLIN 250MG -

Annual Meeting Delegate Handbook

BSIR 2016 ANNUAL MEETING DELEGATE HANDBOOK 1 5TH-1 7TH NOVEMBER 2016 MANCHESTER CENTRAL MANCHESTER 1 MAJOR SPONSORS 2 CONTENTS PAGE CONTENTS 4 Welcome to BSIR 2016 5 Speaker Instructions 6-7 General Information & Social Events WEDNESDAY 4TH NOVEMBER 2015 9 Programme Day 1 10 Scientific Sessions 1 & 2 11 The Graham Plant Proessorship 2016 12 SIRNR Programme 13 Industry Showcases 14 Masterclasses & Workshops THURSDAY 5TH NOVEMBER 2015 15 Programme Day 2 16 Scientific Sessions 3 & 4 17 OOH Intervention Snapshot Survey 18 Masterclasses & Workshops 19 Industry Showcases FRIDAY 6TH NOVEMBER 2015 20 Programme Day 3 21 Scientific Sessions 5 & 6 22 BSIR/BSIRT Trainee Day Programme 24 BSIR Honorary Fellowships: Professor Mike Dake & Dr Giles Maskell 25 BSIR Gold Medal: Professor Anthony Watkinson 26 Wattie Fletcher Lecture: Dr Richard McWilliams 27 Graham Plant Lecturer 28-29 Faculty Biographies 30-31 Faculty Lists 32-33 Exhibition Plan 34 List of Exhibitors 36-46 Exhibitor Bios 48-49 SIRNR Section 50 BSIR AGM 53-61 BSIR Committee Reports 62 BSIR Membership Form 64-69 BSIR/BSIRT Trainee Day Essay Scholars 70-75 BSIR Abstract & Case Study Review 76 VASBI 2017 - Trainee Day Meeting Announcement 77-100 BSIR Abstracts - Scientific Sessions 1-6 101 VASBI 2017 - Meeting Announcement 102-107 BSIR Scientific & Educational Posters 108 The U Foundation 109 BSIR 2017 - Meeting Announcement 110 BSIR IOUK 2017 - Meeting Announcement 3 WELCOME TO BSIR 2016 Dear Colleagues, The theme of this year scientific program continues from the last year’s one which entails covering the widest possible aspects of interventional radiology within the limited conference time. -

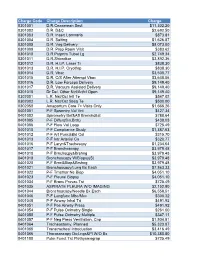

NUMC-CDM-Jan2019.Pdf

Charge Code Charge Description Charge 0301001 D.R.Ceaserean Sect $11,302.20 0301002 D.R. D&C $2,692.50 0301003 D.R. Insert Lamnaria $873.81 0301004 D.R. Salting $1,626.87 0301005 D.R. Vag Delivery $8,073.00 0301009 D.R. Prep Room Visit $383.62 0301010 D.R.Pstprtm Tubal Lg $2,749.34 0301011 D.R.Shirodkar $3,892.36 0301012 D.R. H.I.P. Laser Tr $838.30 0301013 D.R. H.I.P. Cryothrp $838.30 0301014 D.R. Vbac $3,500.77 0301015 D.R. C/S After Attempt Vbac $3,648.06 0301016 D.R. Low Forceps Delivery $9,149.40 0301017 D.R. Vacuum Assisted Delivery $9,149.40 0301018 Dr Del. Other Ntrl/Artfcl Open $9,149.40 0302001 L.R. Nst/Oct Intl Te $547.02 0302002 L.R. Nst/Oct Sbsq Te $500.00 0302050 Antepartum Care 7> Visits Only $1,666.26 0401001 P-F Spromtry Vol Vnt $427.34 0401002 Spirometry Bef&Aft Bronchdilat $788.64 0401005 P-F Diffus(Sin.Brth) $438.03 0401006 P-F Flow Vol Loop $725.49 0401010 P-F Compliance Study $1,387.63 0401012 P-F Art Punc&Bld Col $315.70 0401013 P-F Intr Arterial Ca $320.77 0401016 P-F Laryn&Trachescpy $1,234.64 0401017 P-F Bronchoscopy $3,979.48 0401018 P-F Brnchscpy&Brshng $3,979.48 0401019 Bronchoscopy W/Biopsy(S) $3,979.48 0401020 P-F Brnc&Biop&Brshng $3,979.48 0401021 Bronchoscopy/Lung Bx Each $7,863.33 0401022 P-F Trnsthor Ne Biop $4,051.10 0401023 P-F Pleural Biopsy $4,051.10 0401034 P-F Bronc Provac Tst $725.49 0401035 ASPIRATE PLEURA W/O IMAGING $2,152.80 0401044 Bronchoscopy/Needle Bx Each $6,558.51 0401046 P-F Lungfunc Mbc/Mvv $300.32 0401048 P-F Airway Inhal Trt $491.92 0401051 P-F Pos Airway Press $491.92 0401054 P-F -

IDEAS 2015 Pocket Guide General Information

Interdisciplinary Endovascular Aortic Symposium IDEAS 2015 September 27-29 Lisbon/Portugal Interdisciplinary Endovascular Aortic Symopsium POCKET GUIDE POCKET GUIDE POCKET 2015 EAS INNOVATION | EDUCATION | INTERVENTION Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe ID Scientific & Educational Programme * Corporate Activities 4 General Information from A to Z 10 Session Types Sunday - Scientific Programme 11 SUN Monday - Scientific Programme 14 MON Tuesday - Scientific Programme 17 TUE 19 Corporate Activities 22 Satellite Symposia 39 Learning Centres 48 Technical Exhibition 48 Alphabetical & Numerical List 54 Technical Exhibitors Guide 110 Radiation Protection Pavilion 124 Floor Plans * advertisement-free section in accordance with the document UEMS 2012/30 – the Accreditation of Live Educational Events of the EACCME® (article 33/34) Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe Welcome Address Welcome to the inaugural IDEAS symposium! Keep an eye out for the Endovascular aortic therapies have long been of interest to in- CIRSE Society app update terventional radiologists, vascular surgeons and cardiologists alike – the option to treat the aorta in a minimally invasive New features and design in time for CIRSE 2015! way opens exciting therapeutic possibilities, but realising this dream has been anything but straightforward. Install the CIRSE 2015 event to ensure your access to the best toolkit for the Annual Meeting in Lisbon: Recent technological advances have brought with them fresh enthusiasm for minimally invasive repair of aortic aneurysms – a complex category of interventions that rely heavily on the skills of a well-trained multidisciplinary medical team. • New! paperless session evaluation The various professionals involved in this team all bring their • e-voting own essential skills to the table. -

Percutaneous Transfemoral Repositioning of Malpositioned Central Venous Access Device: a Report of Two Cases

Free full text available from Case Report www.cancerjournal.net Percutaneous transfemoral repositioning of malpositioned central venous access device: A report of two cases ABSTRACT Ashutosh Chauhan, 1 Placement of long term central venous access devices (CVAD) such as chemo ports and Hickman’s catheters are associated with a Kamal Pathak , Manomoy Ganguly definite risk of catheter tip malpositioning. As such, malpositioning runs a risk of venous thrombosis and related complications; it is imperative to reposition the catheter. Percutaneous transfemoral venous approach has been described as a minimally invasive and Departments of safe method for the repositioning. We present two cases in which the CVAD implanted in one subclavian vein got malpositioned in Surgical Oncology and 1Interventional Radiology, contra lateral subclavian vein. A percutaneous transfemoral venous approach utilizing 5 Fr angiographic catheter was successful in Army Hospital (R &R), repositioning of the catheters in both cases. Delhi, India For correspondence: Dr. Ashutosh Chauhan, KEY WORDS: Chemo port, Hickman’s catheter, malposition, repositioning Department of Surgical Oncology, Army Hospital (R &R), Delhi Cantt, Delhi-110 010, India. INTRODUCTION undergone modified radical mastectomy and was E-mail: bolubonkey@ referred to our Center for placement of chemo port rediffmail.com Long term Central Venous Access Devices (CVAD) to facilitate the planned adjuvant chemotherapy. A DOI: 10.4103/0973- are frequently utilized in oncological practice, chemo port was placed in the left subclavian vein 1482.63554 most commonly for chemotherapy and long term under general anesthesia using classical Seldinger PMID: ***** parenteral nutrition. CVAD insertion can be done technique. A check X-ray in the postoperative “blind” using the Seldinger technique or under period demonstrated that the catheter tip had radiological guidance, either by ultrasound or malpositioned into contra lateral subclavian fluoroscopy.[1] Malpositioning of the same is a vein [Figure 1a]. -

Perforation of the Great Vessels During Central Venous Line Placement

Arch Intern Med. 1995 Jun 12;155(11):1225-8. Perforation of the great vessels during central venous line placement. Robinson JF1, Robinson WA, Cohn A, Garg K, Armstrong JD 2nd. Author information Abstract BACKGROUND: Placement of central venous lines for the administration of a variety of therapies has become common practice. The most severe complication of this procedure is perforation of a large vessel, with bleeding, infusion of fluids into an extravascular site, and death. It is not clear from currently available data how often this occurs, what risk factors are associated, and how this complication can be avoided. METHODS: We reviewed the records of all patients who were identified as having perforation of a major vessel during central venous line placement occurring between 1986 and 1993 at the University Hospital, the major teaching facility of the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver. Data collected included the age and sex of the patient, diagnosis, type of catheter and site of placement, operator means and time to the diagnosis of perforation, and outcome. RESULTS: Eleven such complications were identified and 10 of them are reviewed in detail. The overall incidence was less than 1%. Most complications occurred when the right subclavian vein approach was attempted, and they were thought to result from guidewire kinking during advancement of a vessel dilator. All medical specialties and levels of training were involved. Four of 10 patients died of immediate or subsequent complications of the perforation. CONCLUSIONS: Perforation of a great vessel is an uncommon, but often fatal, complication of central venous line placement. -

Pill That Shrinks Uterine Fibroids Gathers Early Data

Mar Issue 17 65 App Suresh Vedantham: Pill that shrinks uterine Profile fibroids gathers early data Page 26 Ulipristal acetate has become the first oral therapy to show positive phase III esultsr for the treatment of uterine fibroids. In early 2017, it demonstrated efficacy and safety in the Michael Dake: treatment of uterine fibroids in two US pivotal studies. TEVAR’s dirty secret hree prominent physicians Page 28 who are strong advocates Tfor treating uterine fibroids using embolization: gynaecologist Bruce McLucas (California, USA) Lutonix AV results and interventional radiologists Jim Spies (Washington, DC, USA) provide tailwind for and Jon Moss (Glasgow, UK) tell Interventional News about how drug-coated balloons drugs will constantly nip at the heels of interventional treatments, and in dysfunctional how it is their side-effect profile that will determine whether patients will arteriovenous fistula tolerate their use. Ulipristal acetate is an treatment investigational drug for the medical treatment of uterine fibroids. It is Scott Trerotola presented the first release a selective progesterone receptor of eight-month data from the Lutonix AV modulator that acts directly on the trial at the Leipzig Interventional Course progesterone receptors in three target (LINC; 24–27 January, Leipzig, Germany) tissues: the endometrium; uterine Uterine fibromyoma and showed that the drug-coated balloon fibroids; and the pituitary gland. (Lutonix 035 AV from Bard) is linked with a Mclucas, who is founder of the In fact, leuprolide now markets a Richter announced positive results significantly higher target lesion patency Fibroid Treatment Collective and three month injection, rather than a from Venus II, the second of two and far fewer reinterventions to maintain whose team performed the first monthly one. -

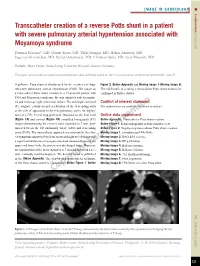

Transcatheter Creation of a Reverse Potts Shunt in a Patient with Severe Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Associated with 2015;11: 121 Moyamoya Syndrome

IMAGE IN CARDIOLOGY INTERVENTIONS FOR HYPERTENSION AND HEART FAILURE Euro Intervention Transcatheter creation of a reverse Potts shunt in a patient with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with 2015;11: Moyamoya syndrome 121 Dietmar Schranz*, MD; Gunter Kerst, MD; Thilo Menges, MD; Hakan Akintürk, MD; Inge van Alversleben, MD; Stefan Ostermayer, MD; Christian Apitz, MD; Axel Moysich, MD Pediatric Heart Center, Justus-Liebig University Hospital, Giessen, Germany This paper also includes accompanying supplementary data published online at: http://www.pcronline.com/eurointervention/84th_issue/21 A palliative Potts shunt is already used for the treatment of drug- Figure 2, Online Appendix and Moving image 1-Moving image 8. refractory pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). We report on The risk/benefit of creating a transcatheter Potts shunt needs to be a transcatheter Potts shunt creation in a 19-year-old patient with confirmed in further studies. PAH and Moyamoya syndrome. He was admitted with haemopty- sis and end-stage right ventricular failure. The technique consisted Conflict of interest statement of retrograde radiofrequency perforation of the descending aorta The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. at the side of apposition to the left pulmonary artery for deploy- ment of a 7 Fr, 22 mm long graft stent. Depicted are the final axial Online data supplement (Figure 1A) and coronal (Figure 1B) computed tomography (CT) Online Appendix. Transcatheter Potts shunt creation. images demonstrating the covered stent expanded to 7 mm, posi- Online Figure 1. Echocardiography in four-chamber view. tioned between the left pulmonary artery (LPA) and descending Online Figure 2. Step-by-step transcatheter Potts shunt creation. -

Tackling the Challenges in the Vascular and Endovascular Arena

CHARING CROSS SPECIAL EDITION March 2016 2016 Vascular & Endovascular Challenges Update Tackling the challenges in the vascular and endovascular arena Peripheral Acute Aortic Venous Arterial Stroke Challenges Challenges Challenges Challenges Halfway through its Controversies, Challenges and Consensus allow the audience to interact with the Challenges Programme—new as of cycle, the Charing Cross Symposium will examine this year the speakers and panel at every stage. 2016—will make its debut. The half-day numerous and varied challenges currently facing the vascular This year, the CX Venous Challenges Programme is being introduced following and endovascular field. The Symposium will be held from 26 to 29 Main Programme will, for the first time, the realisation that a number of strokes April 2016 at Olympia Grand, London, UK. take place on the Symposium’s opening are caused by interventions in the aorta day, exploring the use of various technolo- and manipulations in the arch. his year’s Peripheral Arterial aortic aneurysm trial to be conducted, gies and techniques for the treatment of The purpose of the Acute Stroke Chal- Challenges session will centre and the first to reach fifteen-year follow- superficial and deep venous disease with lenges Main Programme is to encourage around management of the up. The 10-year data, presented at CX emphasis on the latest evidence of when a multidisciplinary approach, such that superficialT femoral artery. Treatment 2010, demonstrated no significant dif- and in which patients they should be used. unwanted emboli to the brain can be man- strategies, varying depending on lesion ferences between endovascular and open The topics for discussion will include aged by clot retrieval, and the optimisation type and length, will be analysed, with repair in terms of mortality. -

Brachial Approach As an Alternative Technique of Fibrin Sheath Removal for Implanted Venous Access Devices

CASE REPORT published: 10 April 2017 doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2017.00020 Brachial Approach As an Alternative Technique of Fibrin Sheath Removal for Implanted Venous Access Devices Charalampos Sotiriadis*, Steven David Hajdu, Francesco Doenz and Salah D. Qanadli Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland Implanted venous access device (IVAD) late dysfunction is commonly caused by fibrin sheath formation. The standard method of endovascular fibrin sheath removal is per- formed via the femoral vein. However, it is not always technically feasible and sometimes contraindicated. Moreover, approximately 4–6 h of bed rest is necessary after the proce- dure. In this article, we describe an alternative method of fibrin sheath removal using the brachial vein approach in a young woman receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. The right basilic vein was punctured, and a long 6°F introducer sheath was advanced into the right subclavian vein. Endovascular maneuvers consisted on advancing Atrieve™ Edited by: Vascular Snare 15–9 mm after catheter insertion in the superior vena cava through a Konstantinos A. Filis, University of Athens Medical 5.2°F Judkins left catheter. IVAD patency was restored without any complication, and School, Greece the patient was discharged immediately after the procedure. In conclusion, fibrin sheath Reviewed by: removal from an obstructed IVAD could be performed via the right brachial vein. Further Andreas M. Lazaris, National and Kapodistrian research is necessary in order to prove efficacy of this technique. University of Athens, Greece Thodur Madabushi Vasudevan, Keywords: brachial access, fibrin sheath removal, implanted venous access devices, vein, endovascular treatment Waikato Hospital, New Zealand *Correspondence: Charalampos Sotiriadis INTRODUCTION [email protected] The use of implanted venous access devices (IVADs) has significantly improved the quality of life in Specialty section: patients requiring long-term intravenous therapy (1).