Intrusion of Overerupted Upper First Molar Using Two Orthodontic Miniscrews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Root Canal Treatment of Permanent Mandibular First Molar with Six Root Canals: a Rare Case

CASE REPORT Turk Endod J 2016;1(1):52–54 doi: 10.14744/TEJ.2016.65375 Root canal treatment of permanent mandibular first molar with six root canals: a rare case Ersan Çiçek,1 Neslihan Yılmaz,1 Murat İçen2 1Department of Endodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Bülent Ecevit University, Zonguldak, Turkey 2Department of Oral Radiology, Faculty of Dentistry, Bülent Ecevit University, Zonguldak, Turkey This case report aims to present the management of a mandibular first molar with six root canals, four in mesial and two in distal root. A 16-year-old male patient who has suffered from localized dull pain in his lower left posterior region for a long time was referred to the endodontic clinic. On clinical examina- tion, neither caries lesion nor restoration was observed on the mandibular molar teeth; but the occlu- sal surface of the teeth had pathologic attrition. The mandibular and maxillary molars were tender to percussion due to bruxism, but there was no tenderness towards palpation. All of the molars revealed normal responses to the vitality tests. It was suggested that he should use the night-guard against brux- ism. After three months, his pain almost completely relieved, but the percussion of the left mandibular molar was still going on. After access cavity preparation, careful examination of the pulp chamber floor with dental loupe and endodontic explorer (DG 16 probe) showed six canal orifices, four of mesially and two of distally. CBCT scan was performed in order to confirm the presence of six canals. Following one year, it was observed that he had no pain. -

Endodontic Therapy in a 3-Rooted Mandibular First Molar: Importance of a Thorough Radiographic Examination

C LINICAL P RACTICE Endodontic Therapy in a 3-Rooted Mandibular First Molar: Importance of a Thorough Radiographic Examination • Juan J. Segura-Egea, DDS, MD, PhD • • Alicia Jiménez-Pinzón, DDS • • José V. Ríos-Santos, DDS, MD, PhD • Abstract This case report describes endodontic therapy on a mandibular first molar with unusual root morphology. In the initial treatment the working length had been determined with only an apex locator; no periapical radiographs had been obtained because the patient was pregnant. The root canal into an additional distolingual root had not been found and was therefore left untreated, which led to treatment failure after 11 months. The radiographic examina- tion performed in a subsequent endodontic treatment allowed detection of the anomalous root and completion of the root canal treatment. The distolingual root canal would have been identified during the initial endodontic therapy if a thorough radiographic examination had been carried out. This report highlights the importance of radiographic examination and points out the need to look for additional canals and unusual canal morphology associated with a mandibular first molar. Radiographic examination during pregnancy is also discussed. MeSH Key Words: dental care; molar/anatomy and histology; tooth root/anatomy and histology; pregnancy © J Can Dent Assoc 2002; 68(9):541-4 This article has been peer reviewed. oot canals may be left untreated during endodontic Thai origin had a third distolingual root. The additional therapy if the dentist fails to identify their presence, root is generally located on the lingual aspect and has a particularly in teeth with anatomical variations or Vertucci type I canal configuration.2 Such a variant has not R 1 extra root canals. -

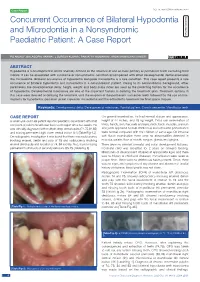

Concurrent Occurrence of Bilateral Hypodontia and Microdontia in a Nonsyndromic Paediatric Patient: a Case Report

Case Report DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2020/43540.14083 Concurrent Occurrence of Bilateral Hypodontia Dentistry Section and Microdontia in a Nonsyndromic Paediatric Patient: A Case Report PG ANJALI1, BALAGOpaL VARMA2, J SURESH KUMAR3, paRVATHY KUMARAN4, ARUN MAMACHAN XAVIER5 ABSTRACT Hypodontia is a developmental dental anomaly defined as the absence of one or more primary or permanent teeth excluding third molars. It can be associated with syndrome or nonsyndromic condition accompanied with other developmental dental anomalies like microdontia. Bilateral occurrence of hypodontia alongside microdontia is a rare condition. This case report presents a rare occurrence of bilateral hypodontia and microdontia in a nonsyndromic patient. Owing to its nonsyndromic background, other parameters like developmental delay, height, weight and body mass index are used as the predicting factors for the occurrence of hypodontia. Developmental milestones are one of the important factors in deriving the treatment plan. Treatment options in this case were directed at delaying the treatment until the eruption of the permanent successor teeth followed by the use of mini- implants for hypodontia, porcelain jacket crown for microdontia and the orthodontic treatment for final space closure. Keywords: Developmental delay, Developmental milestones, Familial pattern, Growth percentile, Mandibular teeth CASE REPORT On general examination, he had normal stature and appearance, A seven-year-old male patient reported paediatric department with chief height of 44 inches, and 18 kg weight. Extra oral examination of complaint of pain in the left lower back tooth region since two weeks. He limbs, hands, skin, hair, nails and eyes, neck, back, muscles, cranium was clinically diagnosed with multiple deep dental caries (74,75,84,85) and joints appeared normal. -

Tooth Size Proportions Useful in Early Diagnosis

#63 Ortho-Tain, Inc. 1-800-541-6612 Tooth Size Proportions Useful In Early Diagnosis As the permanent incisors begin to erupt starting with the lower central, it becomes helpful to predict the sizes of the other upper and lower adult incisors to determine the required space necessary for straightness. Although there are variations in the mesio-distal widths of the teeth in any individual when proportions are used, the sizes of the unerupted permanent teeth can at least be fairly accurately pre-determined from the mesio-distal measurements obtained from the measurements of already erupted permanent teeth. As the mandibular permanent central breaks tissue, a mesio-distal measurement of the tooth is taken. The size of the lower adult lateral is obtained by adding 0.5 mm.. to the lower central size (see a). (a) Width of lower lateral = m-d width of lower central + 0.5 mm. The sizes of the upper incisors then become important as well. The upper permanent central is 3.25 mm.. wider than the lower central (see b). (b) Size of upper central = m-d width of lower central + 3.25 mm. The size of the upper lateral is 2.0 mm. smaller mesio-distally than the maxillary central (see c), and 1.25 mm. larger than the lower central (see d). (c) Size of upper lateral = m-d width of upper central - 2.0 mm. (d) Size of upper lateral = m-d width of lower central + 1.25 mm. The combined mesio-distal widths of the lower four adult incisors are four times the width of the mandibular central plus 1.0 mm. -

Dental Arch Space Changes Following Premature Loss of Primary First Molars

PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY V 30 / NO 4 JUL / AUG 08 Scientific Article Dental Arch Space Changes Following Premature Loss Of Primary First Molars: A Systematic Review William Tunison, BSc1 • Carlos Flores-Mir, DDS, DSc2 • Hossam ElBadrawy, DDS, MSc3 • Usama Nassar, DDS, MSc4 • Tarek El-Bialy, DDS, MSc OSci, PhD5 Abstract: Purpose: The purpose of this study was to consider the available evidence regarding premature loss of primary molars and the implications for treatment planning. Methods: Electronic database searches were conducted—including published information available until July 2007—for available evidence. A methodological quality assessment was also applied. Results: Although a significant number of published articles had dealt with premature primary molar loss, only 3 studies (including a total combined sample of 80 children) had the minimal methodological quality to be considered for this systematic review. Conclusion: A reported immediate space loss of 1.5 mm per arch side in the mandible and 1 mm in the maxilla—when normal growth changes were considered—was found. The magnitude, however, is not likely to be of clinical significance in most cases. Nevertheless, in cases with incisor and/or lip protrusion or a severe predisposition to arch length deficiency prior to any tooth loss, this amount of loss could have treatment implications. (Pediatr Dent 2008;30:297-302) Received June 5, 2007 | Last Revision August 30, 2007 | Revision Accepted August 31, 2007 KEYWORDS: PREMATURE TOOTH LOSS, MIXED DENTITION, SPACE LOSS, TOOTH MIGRATION, SPACE -

Furcation Root Surface Anatomy

the Furcation to the cementoenamal junction were excluded from Morphology sample. in Relative to Periodontal The sample is the same as was used by the author a previously reported study9 and the mesio-distal length Treatment and furcation entrance diameter reported there are used for correlation in the present investigation. a"lS Furcation Root Surface All teeth were sectioned at right angles to the long Anatomy as at a level 2 mm apical to the most apical root division illustrated in I. A fine carborundum disc was Figure 15 used to make the section except in 22 maxillary and by mandibular teeth where a coarser wheel was used. The m.d.sc. Robert C. Bower, latter teeth were not used in the second part of the study- (W. Australia)* The level of section was established using the micrometer screw chuck of a specially constructed tooth sectioning lathe. Recent longitudinal studies of teeth with periodontal The cut tooth surfaces were examined using a dissect- breakdown furcation mm involving the present encouraging ing microscopef with a lOx eyepiece and 10/ioo results for the of such teeth.1"'' Both prognosis pocket micrometer disc to give a stated magnification of 6.3*· elimination!·'' (sometimes necessitating root resection) Measurement the micrometer disc was ' by calibrated and soft tissue to offer a better readaptation" appear using a 1 cm certified plate. One reticle unit was found than was In either of these prognosis formerly imagined. equal to 1.065 mm. to 2 approaches the problem, the anatomy of the furcal The dimensions measured are illustrated in Figures 4 aspects of the roots is likely to influence the result. -

Study of Root Canal Anatomy in Human Permanent Teeth

Brazilian Dental Journal (2015) 26(5): 530-536 ISSN 0103-6440 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440201302448 1Department of Stomatologic Study of Root Canal Anatomy in Human Sciences, UFG - Federal University of Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil Permanent Teeth in A Subpopulation 2Department of Radiology, School of Dentistry, UNIC - University of Brazil’s Center Region Using Cone- of Cuiabá, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil 3Department of Restorative Dentistry, School of Dentistry of Ribeirão Beam Computed Tomography - Part 1 Preto, USP - University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil Carlos Estrela1, Mike R. Bueno2, Gabriela S. Couto1, Luiz Eduardo G Rabelo1, Correspondence: Prof. Dr. Carlos 1 3 3 Estrela, Praça Universitária s/n, Setor Ana Helena G. Alencar , Ricardo Gariba Silva ,Jesus Djalma Pécora ,Manoel Universitário, 74605-220 Goiânia, 3 Damião Sousa-Neto GO, Brasil. Tel.: +55-62-3209-6254. e-mail: [email protected] The aim of this study was to evaluate the frequency of roots, root canals and apical foramina in human permanent teeth using cone beam computed tomography (CBCT). CBCT images of 1,400 teeth from database previously evaluated were used to determine the frequency of number of roots, root canals and apical foramina. All teeth were evaluated by preview of the planes sagittal, axial, and coronal. Navigation in axial slices of 0.1 mm/0.1 mm followed the coronal to apical direction, as well as the apical to coronal direction. Two examiners assessed all CBCT images. Statistical data were analyzed including frequency distribution and cross-tabulation. The highest frequency of four root canals and four apical foramina was found in maxillary first molars (76%, 33%, respectively), followed by maxillary second molars (41%, 25%, respectively). -

Permanent Maxillary First Molar with Two Rooted Anatomy: a Rare Occurrence Dentistry Section

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/35290.11823 Case Report Permanent Maxillary First Molar with Two Rooted Anatomy: A Rare Occurrence Dentistry Section RENITA SOARES1, IDA DE NORONHA DE ATAIDE2, KARLA MARIA CARVALHO3, NEIL DE SOUZA4, SERGIO MARTIRES5 ABSTRACT The basis of successful endodontic therapy resides on sound and thorough knowledge of the root canal anatomy, its variations and the clinical skills. The importance of the knowledge of the anatomy of root canals cannot be overemphasized. Unusual root and root canal morphologies associated with maxillary molars have been reported in several studies, in the literature. The morphology of the maxillary first molar has been studied and reviewed extensively. However the presence of two roots in a maxillary first molar is a rare occurrence and such cases have seldom been reported in literature. This clinical report presents a permanent maxillary first molar with an unusual morphology of two roots with two canals. Keywords: Aberration, Incidence, Root canal systems, Two canals CASE REPORT that permitted magnification. One orifice was located toward the A 42-year-old female patient with a non-contributory medical buccal aspect and was larger in diameter when compared to the history presented to the department of conservative dentistry and typically found buccal orifice in a maxillary first molar. The second endodontics with a chief complaint of pain in the region of the orifice was located towards the palatal aspect [Table/Fig-3]. Further maxillary right first molar. She gave a history of intermittent pain for close inspection and exploration of the pulpal floor was done for the last two months which had increased in intensity since three search of additional orifices with the aid of DG-16 explorer under days. -

Third Molar (Wisdom) Teeth

Third molar (wisdom) teeth This information leaflet is for patients who may need to have their third molar (wisdom) teeth removed. It explains why they may need to be removed, what is involved and any risks or complications that there may be. Please take the opportunity to read this leaflet before seeing the surgeon for consultation. The surgeon will explain what treatment is required for you and how these issues may affect you. They will also answer any of your questions. What are wisdom teeth? Third molar (wisdom) teeth are the last teeth to erupt into the mouth. People will normally develop four wisdom teeth: two on each side of the mouth, one on the bottom jaw and one on the top jaw. These would normally erupt between the ages of 18-24 years. Some people can develop less than four wisdom teeth and, occasionally, others can develop more than four. A wisdom tooth can fail to erupt properly into the mouth and can become stuck, either under the gum, or as it pushes through the gum – this is referred to as an impacted wisdom tooth. Sometimes the wisdom tooth will not become impacted and will erupt and function normally. Both impacted and non-impacted wisdom teeth can cause problems for people. Some of these problems can cause symptoms such as pain & swelling, however other wisdom teeth may have no symptoms at all but will still cause problems in the mouth. People often develop problems soon after their wisdom teeth erupt but others may not cause problems until later on in life. -

Endodontic Management of Mandibular First Molars with Three

Case Report Adv Dent & Oral Health Volume 9 Issue 4- August 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Yousef Hamad Al-Dahman DOI: 10.19080/ADOH.2018.09.555768 Endodontic Management of Mandibular First Molars with Three Distal Root Canals-A Report of Two Cases Al-Hawwas Abdullah Yousef1, Al-Dahman Yousef Hamad2, Aldosary Khalid M3, Al-Dakheel Majed D3, Al-Zuhair Hind4 and Al-Jebaly Asma Suliman4 1Endodontist, Head of Endodontic Division, Dental Department, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 2Endodontist, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 3Consultant in Restorative Dentistry, King Saud University Medical City, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 4General Practitioner, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Submission:June 28, 2018 Published: August 28, 2018 *Corresponding author: Yousef Hamad Al-Dahman, Endodontist, Ministry of Health, P. O. Box: 84891, Riyadh 11681, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Email: Abstract The proper knowledge of root canal anatomy of teeth and its variation is necessary for successful endodontic treatment. Permanent case reports in the literature. However, the presence of three distal canals in distal root is rare. This paper describes two case reports of root canal therapymandibular of permanent first molars mandibular are usually molars having with two mesialthree distal canals root and canals. one or two distal canals. Moreover, middle mesial canal was present in different Keywords: Root canal anatomy; Mandibular molar; Root canal treatment Introduction macroscopic or scanning electron microscopy (SEM) evaluation The knowledge of the anatomy of root canal system and its [20,21], computed tomography (CT) [20], spiral computed endodontic treatment [1]. -

Unusual Anatomy of a Second Maxillary Molar - a Rare Four- Root Configuration Case Report

ARC Journal of Dental Science Volume 1, Issue 2, 2016, PP 13-15 ISSN No. (Online): 2456-0030 http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2456-0030.0102003 www.arcjournals.org Unusual Anatomy of a Second Maxillary Molar - a Rare four- Root Configuration Case Report Dr. Thiago de Almeida Prado Naves Carneiro,DDS, MSc PhD student, Department of Occlusion, Fixed Prostheses, and Dental Materials, School of Dentistry, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia, Minas Gerais Brazil. [email protected] Abstract: Although it is a very rare situation, four-rooted maxillary second molars can occur. The existence of two palatal roots is extremely rare and ranges about only 0.4%. The aim of this study is to present and document a very rare anatomic configuration of a four-rooted maxillary second molar. Anatomic variation in the number of roots and root canals can occur in any tooth, although some cases can be extremely rare as the one presented here.Clinicians should be aware of this possibility before considering any kind of treatment. Keywords: Molar, Dental Anatomy, Anatomical Variation 1. INTRODUCTION Usually the maxillary second molars are described in the literature as a teeth that have 3 roots with 3 or 4 root canals. Understanding of the presence of additional roots and unusual root canals is essential and determines the success of endodontic treatment1. The existence of maxillary second molars with 4 roots (2 buccal and 2 palatal) is extremely rare and ranges about only 0.4%.This information comes from a study that showed, after the examination of two different horizontally angled radiographs of 1,000 maxillary second molars, just four with four roots2. -

Two Sets of Teeth in a Lifetime

Two sets of teeth in a lifetime Two sets of teeth in a lifetime Deciduous teeth: They are the first set of teeth we have and there are altogether 20 of them. They usually start to erupt from around the age of six months until 3 years of age. Permanent teeth: At the age of 6, they sequentially erupt to replace the deciduous teeth which become loose and shed. Deciduous teeth: Space retainer for permanent teeth Normally, underneath the root of each deciduous tooth, there is a developing permanent successor tooth. When it is time for the permanent successor tooth to erupt, the root of the deciduous tooth will resorb and the deciduous tooth will become loose. The place is then taken up by its permanent successor tooth. Deciduous tooth retains the space for its permanent successor tooth. No tooth is dispensable If the deciduous tooth, especially the second deciduous molar, is lost early due to tooth decay, the consequences can be serious: Poor alignment of the teeth The second deciduous molar is already lost The first permanent molar Since the first permanent molar erupts behind the second deciduous molar at the age of 6, the space of the lost second deciduous molar will gradually close up as the first permanent molar moves forward. The permanent tooth is crowded out of the arch when it erupts Later, when the second permanent premolar erupts to replace the second deciduous molar, the permanent tooth will either be crowded out of the dental arch or be impacted and is unable to erupt, leading to poor alignment of the teeth.