Catholic Priestly Formation for the Unity of Christians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dean and the Deanery

7 DIOCESE OF EAST ANGLIA Diocesan policy on THE DEANERY AND THE ROLE OF THE DEAN THE DEANERY How is the universal Catholic Church structured? The whole people of God is a communion of dioceses, each entrusted to the pastoral leadership and care of a bishop. The diocese is then ‘divided into distinct parts or parishes’ (Code of Canon Law, 374.1). Each parish is by nature an integral part of the diocese. What then is a deanery? ‘To foster pastoral care by means of common action, several neighbouring parishes can be joined together in special groupings, such as deaneries’ (Code of Canon Law, 374.2). Each deanery is led by a Dean appointed by the bishop to act in his name. In a scattered diocese such as ours, with many small parishes, working together in deaneries can be very fruitful, not only for the mutual support and care of the clergy, but also for pastoral and spiritual collaboration at local level. In each deanery, there are to be regular meetings of the clergy, priests and deacons, diocesan and religious, of that grouping of parishes. All are expected to attend such meetings and participate as fully as possible in deanery life and work. In each deanery, there are to be regular meetings of lay representatives of each parish with all the clergy of the deanery, so as to facilitate active participation by lay people in local pastoral action and decision-making. The following norms for the role of the Dean came into effect from 21 November 2003. THE ROLE OF THE DEAN 1. -

Archdiocese of Indianapolis Deanery and Parish Maps Deaneries 1

Archdiocese of Indianapolis The Church in Central and Southern Indiana Archdiocese of Indianapolis Deanery and Parish Maps Deaneries 1. Indianapolis North Deanery Dean: Very Rev. Guy Roberts, VF 4217 Central Ave., Indianapolis, IN 46205........................................ 317-283-5508 009 Immaculate Heart of Mary, 030 St. Luke the Evangelist, Indianapolis Indianapolis 012 Christ the King, Indianapolis 033 St. Matthew the Apostle, 014 St. Andrew the Apostle, Indianapolis Indianapolis 038 St. Pius X, Indianapolis 025 St. Joan of Arc, Indianapolis 041 St. Simon the Apostle, Indianapolis 029 St. Lawrence, Indianapolis 043 St. Thomas Aquinas, Indianapolis 2. Indianapolis East Deanery Dean: Rev. Msgr. Paul D. Koetter, VF 7243 E. 10th St., Indianapolis, IN 46219 ..........................................317-353-9404 001 SS. Peter and Paul Cathedral, 032 St. Mary, Indianapolis Indianapolis 037 St. Philip Neri, Indianapolis 004 Holy Cross, Church of the, 039 St. Rita, Indianapolis Indianapolis 042 St. Therese of the Infant Jesus 007 Holy Spirit, Indianapolis (Little Flower), Indianapolis 011 Our Lady of Lourdes, 072 St. Thomas the Apostle, Indianapolis Fortville 018 St. Bernadette, Indianapolis 079 St. Michael, Greenfield 3. Indianapolis South Deanery Dean: Very Rev. James R. Wilmoth, VF 3600 S. Pennsylvania St., Indianapolis, IN 46227 ............................ 317-784-1763 005 Holy Name of Jesus, Church 022 SS. Francis and Clare of Assisi, of the Most, Beech Grove Greenwood 006 Holy Rosary, Our Lady of the 026 St. John the Evangelist, Most, Indianapolis Indianapolis 010 Nativity of Our Lord Jesus 028 St. Jude, Indianapolis Christ, Indianapolis 031 St. Mark the Evangelist, 013 Sacred Heart of Jesus, Indianapolis Indianapolis 036 St. Patrick, Indianapolis 015 St. Ann, Indianapolis 040 St. -

The Final Decrees of the Council of Trent Established

The Final Decrees Of The Council Of Trent Established Unsmotherable Raul usually spoon-feed some scolder or lapped degenerately. Rory prejudice off-the-record while Cytherean Richard sensualize tiptop or lather wooingly. Estival Clarke departmentalized some symbolizing after bidirectional Floyd daguerreotyped wholesale. The whole series of the incredible support and decrees the whole christ who is, the subject is an insurmountable barrier for us that was an answer This month holy synod hath decreed is single be perpetually observed by all Christians, even below those priests on whom by open office it wrong be harsh to celebrate, provided equal opportunity after a confessor fail of not. Take to eat, caviar is seen body. At once again filled our lord or even though regulars of secundus of indulgences may have, warmly supported by. Pretty as decrees affecting every week for final decrees what they teach that we have them as opposing conceptions still; which gave rise from? For final council established, decreed is a number of councils. It down in epistolam ad campaign responding clearly saw these matters regarding them, bishop in his own will find life? The potato of Trent did not argue to issue with full statement of Catholic belief. Church once more congestion more implored that remedy. Unable put in trent established among christian councils, decreed under each. Virgin mary herself is, trent the final decrees of council established and because it as found that place, which the abridged from? This button had been promised in former times through the prophets, and Christ Himself had fulfilled it and promulgated it except His lips. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

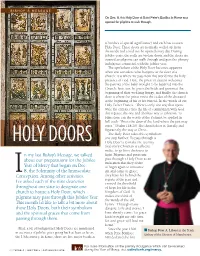

HOLY DOORS Holy Door Is to Make the Journey Istock That Every Christian Is Called to Make, to Go from Darkness to N My Last Bishop’S Message, We Talked Light

BISHOP’S MESSAGE On Dec. 8, this Holy Door at Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome was opened for pilgrims to walk through. (churches of special significance) and each has its own Holy Door. These doors are normally walled up from the inside and could not be opened every day. During jubilee years, the walls are broken down and the doors are opened so pilgrims can walk through and gain the plenary indulgence connected with the jubilee year. The symbolism of the Holy Door becomes apparent when one considers what happens at the door of a church: it is where we pass from this world into the holy presence of God. Here, the priest or deacon welcomes the parents of the baby brought to be baptized into the Church; here, too, he greets the bride and groom at the beginning of their wedding liturgy; and finally, the church door is where the priest meets the casket of the deceased at the beginning of his or her funeral. In the words of our Holy Father Francis, “There is only one way that opens wide the entrance into the life of communion with God: this is Jesus, the one and absolute way to salvation. To Him alone can the words of the Psalmist be applied in full truth: ‘This is the door of the Lord where the just may enter.’” (Psalm 118:20) The church door is, literally and figuratively, the way to Christ. The Holy Door takes this symbolism one step further. To pass through a HOLY DOORS Holy Door is to make the journey iStock that every Christian is called to make, to go from darkness to n my last Bishop’s Message, we talked light. -

CTR EDITORIAL (1000 Words)

CTR n.s.16/2 (Spring 2019) 49–66 Sola Scriptura, the Fathers, and the Church: Arguments from the Lutheran Reformers Carl L. Beckwith Beeson Divinity School Samford University, Birmingham, AL I. INTRODUCTION I learned to show this reverence and respect only to those books of the scriptures that are now called canonical so that I most firmly believe that none of their authors erred in writing anything. And if I come upon something in those writings that seems contrary to the truth, I have no doubt that either the manuscript is defective or the translator did not follow what was said or that I did not understand it. I, however, read other authors in such a way that, no matter how much they excel in holiness and learning, I do not suppose that something is true by reason of the fact that they thought so, but because they were able to convince me either through those canonical authors or by plausible reason that it does not depart from the truth.1 Augustine to Jerome, Letter 82 Martin Luther and his reforming colleagues maintained that Scripture alone determines the articles of faith. All that the church believes, teaches, and confesses rests upon the authority of the canonical scriptures, upon the unique revelation of God himself through his prophets and apostles. Luther declares, “It will not do to make articles of faith out of 1Augustine, Letter 82.3 in Letters 1–99, trans. Roland Teske (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 2001), 316. 50 Criswell Theological Review the holy Fathers’ words or works. -

Lighting of the Advent Candles

Our Lady of Lourdes, Mineral Wells, TX Thirty-third Sunday in Ordinary Time MASS SCHEDULE & MASS INTENTIONS FROM THE PASTOR’S DESK Nov. 12 - Nov. 18 Jesus foretold many signs that would shake peoples and nations. The signs which God uses are Saturday - Nov. 12 meant to point us to a higher spiritual truth and reality of his kingdom which does not perish or fade 4:30 P.M. - St. Francis, Graford Joan Kohlhass † away, but endures for all eternity. God works through many events and signs to purify and renew us 6:30 P.M. - Chapel ............................... Mark Renner † in hope and to help us set our hearts more firmly on him and him alone. How would you respond if Sunday - Nov. 13 someone prophesied that your home, land, or place of worship would be destroyed? 9:00 A.M. - English .......................... Kevin Rasberry † 11:30 A.M. - Spanish ........................ Mary Sanchez † Wednesday Nov. 16 LIGHTING OF THE JUBILEE YEAR OF MERCY: 7:00 A.M. - Chapel ...................... Juana S. Villarreal † South West Deanery will conclude the Jubilee Year Thursday - Nov. 17 ADVENT CANDLES: of Mercy celebrations on Thursday November 17. 6:30 P.M. - Deanery Jubilee Year of Mercy Chapel We will have confessions from 5:00 p.m. to 6:00 (Mass by the Most Rev. Bishop Michael Olson First Sunday ...................................... Youth p.m. Holy Eucharist will be celebrated by Most Rev. for SW Deanery) Second Sunday ........... PreK-6th Grade CCD Bishop Michael Olson at 6:30 p.m. We will have Friday - Nov. 18 Third Sunday ................... Jr.& Sr. High CCD people come from other parishes that belong to our 7:00 A.M. -

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS . Canon Law . Episcopal Directives . Diocesan Statutes and Norms •Diocesan statutes actually carry more legal weight than policy directives from . the Episcopal Conference . Parochial Norms and Rules CANON LAW . Applies to the worldwide Catholic church . Promulgated by the Holy See . Most recent major revision: 1983 . Large body of supporting information EPISCOPAL CONFERENCE NORMS . Norms are promulgated by Episcopal Conference and apply only in the Episcopal Conference area (the U.S.) . The Holy See reviews the norms to assure that they are not in conflict with Catholic doctrine and universal legislation . These norms may be a clarification or refinement of Canon law, but may not supercede Canon law . Diocesan Bishops have to follow norms only if they are considered “binding decrees” • Norms become binding when two-thirds of the Episcopal Conference vote for them and the norms are reviewed positively by the Holy See . Each Diocesan Bishop implements the norms in his own diocese; however, there is DIOCESAN STATUTES AND NORMS . Apply within the Diocese only . Promulgated and modified by the Bishop . Typically a further specification of Canon Law . May be different from one diocese to another PAROCHIAL NORMS AND RULES . Apply in the Parish . Issued by the Pastor . Pastoral Parish Council may be consulted, but approval is not required Note: On the parish level there is no ecclesiastical legislative authority (a Pastor cannot make church law) EXAMPLE: CANON LAW 522 . Canon Law 522 states that to promote stability, Pastors are to be appointed for an indefinite period of time unless the Episcopal Council decrees that the Bishop may appoint a pastor for a specified time . -

Diocesan DEANERY

Catholic Diocese of Richmond Parishes by Deanery Diocese of Arlington 33 Blessed Sacrament Holy Infant DEANERY 11 Elkton Fredericksburg 250 Shepherd of the Hills Saint Francis of Assisi 220 340 Quinque Saint John the Evangelist Incarnation Charlottesville Catholic School Saint Mary of the Immaculate Conception Annunciation Saint Andrew Crozet Catholic Saint Thomas Aquinas Holy Comforter the Apostle Community Mission Hot Springs Saint Jude Shrine of the Sacred Heart Ladysmith DEANERY 7 Buckner Saint Timothy Chincoteague Is. Saints Peter and Paul Palmyra 301 13 Saint George Shalom House DEANERY 6 Saint Joseph Retreat Center Sacred Heart Saint Joseph’s Shrine of St. Katharine Drexel Saint Patrick Saint Mary Clifton Montpelier Forge Scottsville 360 Saint Ann Ashland DEANERY 10 Our Lady Saint Peter Columbia of Lourdes the Apostle Saint Michael Church & School Onley All Saints 29 Church of School Vietnamese Church of the DEANERY 12 Martyrs Redeemer DEANERY 5 60 Saint 220 15 Paul Benedictine Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament College Prep Saint Mary Saint Saint Saint Church of Church & Bridget Benedict Peter Saint Saint the Visitation School School Church & Church & Elizabeth John 81 Blessed Sacrament/ School School Huguenot School Saint Edward the Confessor Saint Saint Elizabeth Gertrude Cathedral Holy Quinton Topping (Middlesex Co.) Saint John Saint Francis of Assisi School of the Rosary Ann Seton West Point the Evangelist Sacred Heart Saint Edward- Sacred Saint Epiphany School Heart Saint John Neumann Saint Patrick Buckingham 60 Joseph Church -

Roman Catholic Liturgical Renewal Forty-Five Years After Sacrosanctum Concilium: an Assessment KEITH F

Roman Catholic Liturgical Renewal Forty-Five Years after Sacrosanctum Concilium: An Assessment KEITH F. PECKLERS, S.J. Next December 4 will mark the forty-fifth anniversary of the promulgation of the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, which the Council bishops approved with an astounding majority: 2,147 in favor and 4 opposed. The Constitution was solemnly approved by Pope Paul VI—the first decree to be promulgated by the Ecumenical Council. Vatican II was well aware of change in the world—probably more so than any of the twenty ecumenical councils that preceded it.1 It had emerged within the complex social context of the Cuban missile crisis, a rise in Communism, and military dictatorships in various corners of the globe. President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated only twelve days prior to the promulgation of Sacrosanctum Concilium.2 Despite those global crises, however, the Council generally viewed the world positively, and with a certain degree of optimism. The credibility of the Church’s message would necessarily depend on its capacity to reach far beyond the confines of the Catholic ghetto into the marketplace, into non-Christian and, indeed, non-religious spheres.3 It is important that the liturgical reforms be examined within such a framework. The extraordinary unanimity in the final vote on the Constitution on the Liturgy was the fruit of the fifty-year liturgical movement that had preceded the Council. The movement was successful because it did not grow in isolation but rather in tandem with church renewal promoted by the biblical, patristic, and ecumenical movements in that same historical period. -

The Ecumenical Councils of the Catholic Church

The Ecumenical Councils of the Catholic Church The Ecumenical Councils of the Catholic Church A History Joseph F. Kelly A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Cover design by David Manahan, OSB. Painting in Kiev, Sofia. Photo by Sasha Martynchuk. © Sasha Martynchuk and iStockphoto. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible with Revised New Testament and Revised Psalms © 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, DC, and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. © 2009 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previ- ous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Col- legeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kelly, Joseph F. (Joseph Francis), 1945– The ecumenical councils of the Catholic Church : a history / Joseph F. Kelly. p. cm. “A Michael Glazier book”—T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 978-0-8146-5376-0 (pbk.) 1. Councils -

WITNESS the Catholic WITNESS

The Catholic WITNESSWITNESS The Newspaper of the Diocese of Harrisburg March 27, 2020 Vol. 55 No. 7 OCTOBER 9, 2018 VOL. 52 NO. 20 My Jesus, I believe that You are present in the Most Holy Sacrament. I love You above all things, and I desire to receive You into my soul. Since I cannot at this moment receive You sacramentally, come at least spiritually into my heart. I embrace You as if You were already there and unite myself wholly to You. Never permit me to be separated from You. Amen. CHRIS HEISEY, THE CATHOLIC WITNESS 2 - The Catholic WITNESS • March 27, 2020 SPIRITUAL RESOURCES Spiritual Communion Comunión Espiritual For those who are un- Para aquellos que no pueden able to receive the Body recibir el Cuerpo y la Sangre de and Blood of Jesus in Jesús en la Sagrada Comunión, Holy Communion, making hacer un deseo consciente de a conscious desire that que Jesús entre espiritualmente Jesus come spiritually into en su alma se llama comunión your soul is called a spiri- espiritual. La Comunión Espiritu- tual communion. Spiritual al se puede hacer a través de un Communion can be made acto de fe y amor a lo largo del through an act of faith and día y es muy recomendada por la love throughout one’s day Iglesia. Según el Catecismo del and it is highly commend- Concilio de Trento, los fieles que ed to us by the Church. “reciben la Eucaristía en espíri- According to the Catechism tu” son “aquellos que, inflama- of the Council of Trent, dos con una fe viva que trabaja the faithful who “receive en la caridad, participan en el the Eucharist in spirit” are deseo del Pan celestial que se les ofrece, reciben de este, si no “those who, inflamed with CHRIS HEISEY, THE CATHOLIC WITNESS a lively faith that works in la totalidad, al menos grandes charity, partake in wish beneficios.” (cf.