A New Geography of Local Government in Cornwall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

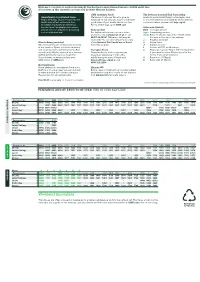

Weekend Timetables

Welcome to our guide to services showing St Ives Bay Line trains between Penzance, St Erth and St Ives. All services in this timetable are operated by Great Western Railway. GWR Customer Panel The Devon & Cornwall Rail Partnership Amendments to published times We have a Customer Panel to give us works to promote rail travel in the region and Public Holidays and rail improvement feedback on our services and to contribute to improve services and facilities at our stations. works may affect services in this good ideas. If you would like to join the For more details, please visit dcrp.org.uk timetable, especially at weekends. Panel, please sign up at GWR.com For the latest timetable information, Notes and symbols please visit our website or download National Rail Bold Through service our smartphone app. For further information on train times Light Connecting service and fares, visit nationalrail.co.uk or call Green Runs on certain days only. Please check 03457 48 49 50* (24 hours, call may be the note at the top of the column recorded). You can also download a copy ) PlusBus available Want to bring your bike? of the National Rail Conditions of Travel a Arrival time Bike reservations are compulsory on many from this website. d Departure time of our services. Space is limited on board, f Arrives at 0752 on Mondays and so we operate a strict first-come, first- Transport Focus x Stops on request. Please tell the Conductor served policy. Book a space at your nearest Transport Focus is the independent if you wish to leave. -

The Stannaries

THE STANNARIES A STUDY OF THE MEDIEVAL TIN MINERS OF CORNWALL AND DEVON G. R. LEWIS First published 1908 PREFACE THEfollowing monograph, the outcome of a thesis for an under- graduate course at Harvard University, is the result of three years' investigation, one in this country and two in England, - for the most part in London, where nearly all the documentary material relating to the subject is to be found. For facilitating with ready courtesy my access to this material I am greatly indebted to the officials of the 0 GEORGE RANDALL LEWIS British Museum, the Public Record Office, and the Duchy of Corn- wall Office. I desire also to acknowledge gratefully the assistance of Dr. G. W. Prothero, Mr. Hubert Hall, and Mr. George Unwin. My thanks are especially due to Professor Edwin F. Gay of Harvard University, under whose supervision my work has been done. HOUGHTON,M~CHIGAN, November, 1907. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION purpose of the essay. Reasons for choice of subject. Sources of informa- tion. Plan of treatment . xiii CHAPTER I Nature of tin ore. Stream tinning in early times. Early methods of searching for ore. Forms assumed by the primitive mines. Drainage and other features of medizval mine economy. Preparation of the ore. Carew's description of the dressing of tin ore. Early smelting furnaces. Advances in mining and smelt- ing in the latter half of the seventeenth century. Preparation of the ore. Use of the steam engine for draining mines. Introduction of blasting. Pit coal smelting. General advance in ore dressing in the eighteenth century. Other improvements. -

Gilly Vean Farm South Cornwall

Gilly Vean Farm South Cornwall Gilly Vean Farm GWENNAP, SOUTH CORNWALL, TR16 6BN Farmhouse set centrally within extensive grounds with equestrian facilities, countryside views and potential for holiday lets. Available for the first time in 26 years Secluded position within private grounds Close to both Falmouth and Truro Charming main residence Rolling countryside views Planning consent for holiday lettings Sand school, stables, tack and feed rooms Approx. 26.55 acres Falmouth – 6.5 Truro – 8 St Agnes – 10 Helford – 10.5 Cornwall Airport (Newquay) – 26.5 (all distances are approximate and in miles) Savills Truro 73 Lemon Street Truro, TR1 2PN Tel: 01872 243200 [email protected] savills.co.uk THE PROPERTY Originally built in the 1850s, Gilly Vean Farm is located at the end of a long private driveway set within the centre of its own grounds, therefore affording great privacy. The original farmhouse has been extended to join the adjacent traditional buildings and now provides unique and highly versatile 4-bedroomed accommodation with two principal reception rooms, snug, a home office and the potential for an integral annexe. There is extensive stabling and planning consent for conversion. Entering the property through the charming and picturesque courtyard, a glazed entrance lobby leads through to the kitchen with an outlook over the front courtyard, arranged around a central island and includes an electric range within the former fireplace, and through to the main body of the farmhouse. The study and snug lead on to a beautiful sitting room defined by painted beams and an open fireplace with the conservatory leading out to the attractive and mature front gardens. -

Town Clerks Report Council 28Th September 2020

TRURO CITY COUNCIL Town Clerk’s Department Municipal Buildings Boscawen Street Truro TR1 2NE Tel. (01872) 274766 Fax. (01872) 225572 CITY OF TRURO www.truro.gov.uk Roger Gazzard email: [email protected] Town Clerk F6/3/RG/RD October 2020 YOU ARE HEREBY SUMMONED TO ATTEND A MEETING OF THE TRURO CITY COUNCIL TO BE HELD AT 7.00 pm ON MONDAY 26 OCTOBER 2020 VIA ZOOM VIRTUAL MEETINGS For the transaction of the under-mentioned business:- There will be a presentation regarding the forthcoming Langarth Planning Application at 6.30pm, prior to this meeting. 1 Prayers Prior to the formal business of the Council, The Dean of Truro, the Mayor’s Chaplain, to say prayers. 2 To receive apologies for absence 3 Disclosure or Declarations of Interest Councillors will be asked to make disclosures or declarations of interest in respect of items on this agenda 4 To confirm the Minutes of the Council Meeting held 28 October 2020 pages 87-92 (Minute Nos: 180 - 195). 5 Open Session for Cornwall Councillors verbal, written or tabled reports (15 minutes) This is an opportunity to discuss Cornwall Council issues relevant to the Council. If there are any matters that require a Council decision, please notify the Town Clerk four working days before the meeting. 6 Open Session for Electors of Truro – Verbal Questions (15 minutes) This is an opportunity for electors to raise issues with the Council. The Council is unable to make any resolutions at this meeting on any issues raised 7 To receive Verbal Communications from the Mayor 8 To receive Correspondence 9 Question Time pursuant to Standing Order No. -

Lostwithiel Neighbourhood Plan

Lostwithiel Neighbourhood Plan Part One: Context and Framework Draft November 2017 Produced by: Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group on behalf of Lostwithiel Town Council Taprell House, North Street Lostwithiel Cornwall PL22 0BL Tel: 01208 872323 Website: http://www.lostwithielplan.org.uk Page 1 An Introduction from the Mayor The Town Council welcomed the opportunity to develop a Neighbourhood Plan that would shape the future of the town for the next twenty years and to meet the needs of future generations of residents in Lostwithiel. With the help of a Steering Group of local residents, this Plan has been drawn up with the intention of reflecting and sustaining the sense of community and heritage that is so important to all who live in the town. We see this Plan not simply as a practical administrative device to guide planning decisions. We have endeavoured to engage with you and to consult you over what you wish to see in the town and we hope it gives a vision of the town and its future that all who live in it will embrace. The Plan will be put to you in a local Referendum, which will be your chance to endorse the future that the Council is committed to realising. Pam Jarrett Mayor of Lostwithiel Page 2 Contents Introduction: The Purpose of the Plan ............................................................................... 5 Purpose of the plan ................................................................................................................................ 5 How This Plan Was Constructed ....................................................................................... -

Estuary Watch Lelant, St Ives

Estuary Watch Lelant, St Ives Estuary Watch, Vicarage Lane, Lelant, St Ives, TR26 3JZ A highly individual, energy efficient and newly built family home, thoughtfully arranged to ensure versatility, minimalist style, wonderful natural light and far- reaching views towards the estuary and beyond. Enjoying a tucked away setting, this superb 2019-built contemporary home is within easy access of west Cornwall’s most beautiful beaches, towns and villages; the perfect gateway to some of the county’s finest lifestyle opportunities. • Completed in 2019 • High quality and energy efficient • Meticulous standard of presentation • Three floors • Five bedrooms, four bath / shower rooms • Far reaching estuary views • Garden and two balconies • Garage and parking • Over 2,300 sq ft plus garage & cellar Lelant branchline railway halt – 350 yards; West Cornwall Golf Club – 0.5; Porthkidney beach – 1; St Erth (mainline and branchline rail) – 1; Carbis Bay – 1.7; St Ives – 2.8; Gwithian – 5.5; Marazion – 5.5; Truro - 23; Cornwall Airport (Newquay) – 36 (all distances are approximate and in miles) The location Estuary Watch is one of the most surprising and exciting contemporary homes to have been built in Lelant in recent years. With its light, spacious and imaginative accommodation, with meticulous attention to detail and modern style, this is the perfect place from which to explore the rewarding lifestyle that west Cornwall has to offer. Situated within a short walk of the beautiful sandy beach at Porthkidney, with The Towans on the other side of the estuary, the small village of Lelant is perfectly positioned for Carbis Bay, St Ives and Gwithian Bay, and so convenient for exploring west Cornwall and further south to Mount’s Bay. -

E-Government Progress Review South Kesteven District Council Audit

audit 2003/2004 E-government Progress Review South Kesteven District council INSIDE THIS REPORT PAGE 2-6 Summary PAGES 7-20 Detailed Report • Progress against ESD target (BVPI-157) resources • IEG3 ‘Traffic Lights’ assessment • Checklist for members and chief executives: • Leadership • Transforming services • Renewing local democracy • Promoting economic vitality PAGES 24-33 Appendices • Appendix 1 - SKDC Checklist for Members and Chief Executives • Appendix 2 - Comparative charts based on IEG3 ‘Traffic Lights’ • Appendix 3 – Good practice in Lincolnshire districts • Appendix 4 – Action plan Reference: KE011 E-government Progress Review Date: August 2004 audit 2003/2004 SUMMARY REPORT Introduction E-government is more than technology or the Internet or service delivery: it is about putting citizens at the heart of everything councils can do and building service access, delivery and democratic accountability around them. E-government includes exploiting the power of information and communications technology to help transform the accessibility, quality and cost-effectiveness of public services. It can be used to revitalise the relationship between citizens and the public bodies who work on their behalf. Local e-government is the realisation of this vision at the point where the vast majority of public services are delivered. In March 1999 the government produced a white paper Modernising Government, which included a new package of reforms and targets. The intention was that by 2002, 25 per cent of dealings by the public with government, including local government and the NHS, should have been capable of being conducted electronically, with 100 per cent of dealings capable of electronic delivery by 2005. In November 2002 the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister published the National Strategy for Local e-government. -

Vebraalto.Com

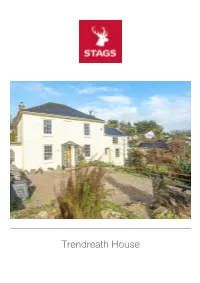

Trendreath House Trendreath House , Lelant, St. Ives, Cornwall TR26 3EG SITUATION METHOD OF SALE Trendreath House is situated in the popular village Trendreath House is offered for sale by public of Lelant between Hayle and Carbis Bay. auction. The Vendor reserves the right to sell prior to auction, withdraw or amend the property at DESCRIPTION auction. The house stands in a south facing position adjacent to the road and presents a quality period TENURE AND POSSESSION residence with light and airy accommodation Freehold with vacant possession on completion. which is well-presented. It offers character SPECIAL CONDITIONS OF SALE/AUCTION accommodation with features reflecting its status INFORMATION PAC as a Listed Building of Special Architectural or Any particulars, remarks or stipulations contained Historic Significance such as slate flagstone floors, herein shall be deemed to form part of the Special window seats, arched windows, cornicing and so Conditions of Sale/Auction Information Pack and in forth. case of any inconsistencies, the provisions of the latter shall prevail. The Special Conditions of On the ground floor is an Entrance Hall off which is Sale/Auction Information Pack will be available for a spacious Drawing Room with direct access inspection at Stags’ Truro office and a copy may through to a Study/Playroom with Gothic arched be purchased from the Vendor’s Solicitors. It is windows. There are separate Sitting Room and assumed that the Purchaser will have made all Dining Rooms and a Kitchen/Living Room with a necessary enquiries prior to the auction. range of bespoke units with worktop surfaces, mains gas fired Aga and deep sink unit. -

GOGMAGOG-2014-Evaluation-Report.Pdf

GoldenTree productions [email protected] www.goldentree.org.uk ANCIENT CORNISH MYTH SPACEEVALUA-AGE STORYTELLINGTION REPORT! EPIC IMMERSIVE THEATRE GOGMAGOG 2014 EVALUATION REPORT CONTENTS' 1.'SUMMARY''' 2.'ARTISTIC'QUALITY'' 3.'THE'TOUR' 4.'COMMUNITY'ENGAGEMENT'' 5.'PUBLICITY/MARKETING'' 6.'PARTNERSHIPS'' 7.'KEY'LEARNING'&'DEVELOPMENT'PRIORITIES'' ' APPENDICES;'' i) EVALUATION'STRATEGY' ii) AUDIENCE'FEEDBACK;''' a) ONLINE'SURVEY,'' b) FACEBOOK'COMMENTS,'' c) TWEETS,'' d) ‘GOLDEN'TICKET’'INTERVIEWS' iii) INTERN'FEEDBACK' ! ! …I think you've made a masterpiece -audience email feedback! ! 2! ' GOGMAGOG%2014%EVALUATION!REPORT! 1.'SUMMARY''' WHAT'WE'SAID'WE'WOULD'DO:'' Our experimental, experiential amphitheatre arrives in iconic locations across Cornwall. In the run- up we have developed ‘cultural offerings’ with local community groups and co-curate a daytime festival programme. The big night arrives and, as in a medieval Cornish ‘plen-an-gwari’, we are ready to share an extraordinary, immersive, participative experience. We surround and involve the audience with epic theatrical storytelling of the highest quality. Our contemporary reworking of the ancient ‘Gogmagog’ legend reveals a timeless story of conflict, survivors and asylum- seeking. Notions about identity and belonging are challenged; distinctiveness and diversity are celebrated; community is reinforced. ! ! ! DID'WE'DO'THIS?' ! Yes! We designed and built a ‘wagon-train’ of set and scenery that encircled our audiences. We toured this ‘mobile plen-an-gwari’ to iconic locations from cliff-tops to castles across Cornwall. We hosted afternoon programmes of Cornish ‘cultural offerings’ with local community groups. We re-interpreted our ancient Cornish myth to create an epic piece of immersive theatre. We devised an audience experience that allowed each person to find their own level of involvement and participation. -

Advertising Signs On, Or Adjacent to the Highway

CORNWALL COUNTY COUNCIL COMMUNITY LIFE POLICY DEVELOPMENT AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE ADVERTISING SIGNS ON, OR ADJACENT TO THE HIGHWAY SINGLE ISSUE PANEL DRAFT REPORT March 2005 CONTENTS ____________________________________________________________________ Executive Summary and Recommendations 1. Introduction 1 2. The Panel’s Findings 2 3. Conclusions 12 Appendix 1 – Summary of the Terms of Reference 13 Appendix 2 – Panel Members and Meetings 15 Appendix 3 – Witnesses 15 Appendix 4 – Employers Work Instructions – 16 Cumbria County Council EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Over the last 2-3 years there has been a notable increase in the amount of unauthorised advertising material being placed on, or adjacent to the highway. This varies from fly posting on the back of road signs, to trailers specifically designed to be left on, or adjacent to the roadside and has led to increasing concern within the County Council, district councils and from the general public. The removal of unauthorised signing is a controversial service area. In the past, programmes of work to remove signs have generated adverse comments from businesses and events organisers. The organisers of smaller events in particular often feel aggrieved as the display of signs and or flyers in the locality are often the only publicity for their events. At the present time the County Council does not have a formalised policy on the way in which it deals with advertising signs on or adjacent to the highway, and as a result officers instead adhere to a recognised working practice . As a result, the Advertising Signs on, or Adjacent to the Highway Single Issue Panel was established to consider the issues surrounding unauthorised signs which would influence the development of the Council’s policy. -

Ref: LCAA1820

Ref: LCAA7251 Offers in excess of £2,000,000 The Old Vicarage, Brush End, Lelant, St Ives, Cornwall FREEHOLD PRELIMINARY SALES PARTICULARS IN LIEU OF PRINTED BROCHURE A beautifully restored and substantial former vicarage dating from the late Regency period providing 6 bedrooms, 5 bath/shower room accommodation along with detached studio/home office and beautifully appointed 1 bedroomed annexe. Situated on the western edge of Lelant and enjoying glorious views over undulating farmland and woodland towards Trencrom Hill close to St Ives and the beautiful beaches of the south Cornish coastline. In all, approximately 1.8 acres. 2 Ref: LCAA7251 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: reception hall, drawing room, sitting room, dining room, boot room, cloakroom/wc, rear lobby, cellar, utility room, kitchen/dining/family room. First Floor: landing, master bedroom with walk-in wardrobes, en-suite bathroom and separate shower room. Guest bedroom with en-suite shower room. Bathroom, additional shower room, 3 further bedrooms. Attic Floor: 2 further bedrooms. THE MEWS Open-plan living/kitchen/dining room, bedroom with en-suite shower room. Outside: beautifully landscaped gardens and grounds with swathes of lawn and a plethora of mature flowering trees, plants and shrubs. Gated drive, detached double garage, parking for numerous vehicles and separate studio/home office. In all, approximately 1.8 acres. 3 Ref: LCAA7251 DESCRIPTION • A handsome and beautifully restored period house. • Currently running as a successful, stunning 5* luxury holiday let (sleeping 12) through Pure Cornwall. Please refer to their website www.purecornwall.co.uk for more information and availability. • Large impressive reception hall. -

34 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

34 bus time schedule & line map 34 Pool - Helston - The Lizard View In Website Mode The 34 bus line (Pool - Helston - The Lizard) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Culdrose: 6:00 PM (2) Helston: 7:00 PM (3) Helston: 1:45 PM - 11:47 PM (4) Lizard: 6:35 AM - 10:15 PM (5) Penhale: 3:26 PM (6) Redruth: 6:32 AM - 8:37 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 34 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 34 bus arriving. Direction: Culdrose 34 bus Time Schedule 30 stops Culdrose Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:00 PM Monday Not Operational Railway Station, Redruth Station Road, Redruth Civil Parish Tuesday Not Operational Library, Redruth Wednesday Not Operational Clinton Road, Redruth Thursday Not Operational Clinton Road, Redruth Civil Parish Friday Not Operational Opie Oils, Redruth Saturday Not Operational Penventon Terrace, Four Lanes Opies Row, Four Lanes B3297, Carn Brea Civil Parish 34 bus Info Direction: Culdrose Victoria Inn, Four Lanes Stops: 30 Trip Duration: 51 min Trevarren Avenue, Four Lanes Line Summary: Railway Station, Redruth, Library, Penluke Close, Carn Brea Civil Parish Redruth, Clinton Road, Redruth, Opie Oils, Redruth, Penventon Terrace, Four Lanes, Opies Row, Four Sportsmans Arms, Four Lanes Lanes, Victoria Inn, Four Lanes, Trevarren Avenue, Church Road, Carn Brea Civil Parish Four Lanes, Sportsmans Arms, Four Lanes, Short Stay School, Nine Maidens, Postbox, Carthew, Phone Short Stay School, Nine Maidens Box, Burras, Ennis Cottage, Farms Common, Bus Shelter, Crelly,