Characterizations of Imazighen from Britain and Morocco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

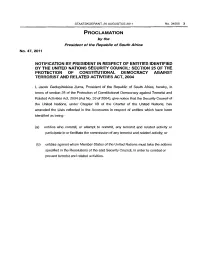

Protection of Constitutional Democracy Against Terrorist and Related Activities Act, 2004

STAATSKOERANT, 25 AUGUSTUS 2011 No.34555 3 PROCLAMATION by the President of the Republic of South Africa No. 47, 2011 NOTIFICATION BYPRESIDENT IN RESPECT OF ENTITIES IDENTIFIED BY THE UNITED NATIONS SECURITY COUNCIL: SECTION 25 OF THE PROTECTION OF CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY AGAINST TERRORIST AND RELATED ACTIVITIES ACT, 2004 I, Jacob Gedleyihlek.isa Zuma, President of the Republic of South Africa, hereby, in terms of section 25 of the Protection of Constitutional Democracy against Terrorist and Related Activities Act, 2004 (Act No. 33 of 2004), give notice that the Security Council of toe United Nations, under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations, has amended the Lists reflected in the Annexures in respect of entities which have been identified as being (a) entities who commit, or attempt to commit, any terrorist and retated activity or participate in or facilitate the commission of any terrorist and related activity; or (b) entities against whom Member States of the United Nations must take the actions specified in the Resolutions of the said Security Council, in order to combat or prevent terrorist and related activities. 4 No. 34555 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 25 AUGUST 2011 This Proclamation. and the Annexure thereto, shall also be published on the South African Police Service Internet website: http://www.saps.gov.za The United Nations Security Council regularly updates the lists in respect of additions and deletions. The updated lists and key thereto are electronically available on the following websites on the Internet: http:/fwww.un.orgtsc/committees/1267/AQiist.html http://www.un.org!sc/committees/1988/List.html http~//www.saps.gov.za (link to above website) Future deletions or additions to the lists will be published as and when information to that effect is received from the United Nations Security Council. -

000 INICIALES English Maquetación 1

004 MEDIEVAL_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:43 Página 72 004 MEDIEVAL_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:43 Página 73 The Medieval World 004 MEDIEVAL_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:43 Página 74 Al-Andalus (8th-15th Century) Islam, a religious movement born on the Arabian Peninsula, spread to other geographical regions after the Hijra (622), when its founder, Muhammad, migrated from Mecca to Medina. In a short time Muhammad’s successors conquered a vast territory stretching from central Asia to the Atlantic. In the Mediterranean, they occupied North Africa and reached the Iberian Penin- sula in 711, sweeping up and over the Pyrenees to Poitiers, where their ad- vance was finally halted by the Franks in 732. Al-Andalus was how the Muslims referred to the Iberian territory under their control, whose borders shifted repeatedly in the following centuries until the end of Muslim rule on the peninsula in 1492. 74 In the early years (711-756), Al-Andalus was a province of the Umayyad Em- pire governed by an emir who answered to the caliph at Damascus. In 750 the Umayyads were overthrown by the Abbasids, but one Umayyad prince, ‘Abd al-Rahman, survived and conquered Córdoba (756), proclaiming himself emir and founder of the Umayyad dynasty of Al-Andalus. The capital of 'Abd al-Rahman II and various objects that still display the late Hispano-Roman and Visigothic traditions date from this period. In 929 ‘Abd al-Rahman III established the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba, a state in its own right with no ties of dependency on the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad, and founded the palatial city of Madinat al-Zahra, a symbol of Umay- yad power and splendour. -

The Heritage of AL-ANDALUS and the Formation of Spanish History and Identity

International Journal of History and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) Volume 3, Issue 1, 2017, PP 63-76 ISSN 2454-7646 (Print) & ISSN 2454-7654 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-7654.0301008 www.arcjournals.org The Heritage of AL-ANDALUS and the Formation of Spanish History and Identity Imam Ghazali Said Indonesia Abstract: This research deals with the Islamic cultural heritage in al-Andalus and its significance for Spanish history and identity. It attempts to answer the question relating to the significance of Islamic legacies for the construction of Spanish history and identity. This research is a historical analysis of historical sources or data regarding the problem related to the place and contribution of al-Andalus’ or Islamic cultural legacies in its various dimensions. Source-materials of this research are particularly written primary and secondary sources. The interpretation of data employs the perspective of continuity and change, and continuity and discontinuity, in addition to Foucault’s power/knowledge relation. This research reveals thatal-Andalus was not merely a geographical entity, but essentially a complex of literary, philosophical and architectural construction. The lagacies of al-Andalus are seen as having a great significance for the reconstruction of Spanish history and the formation of Spanish identity, despite intense debates taking place among different scholar/historians. From Foucauldian perspective, the break between those who advocate and those who challenge the idea of convivencia in social, religious, cultural and literary spheres is to a large extent determined by power/knowledge relation. The Castrian and Albornozan different interpretations of the Spanish history and identity reflect their relations to power and their attitude to contemporary political situation that determine the production of historical knowledge. -

Early Colonial History Four of Seven

Early Colonial History Four of Seven Marianas History Conference Early Colonial History Guampedia.com This publication was produced by the Guampedia Foundation ⓒ2012 Guampedia Foundation, Inc. UOG Station Mangilao, Guam 96923 www.guampedia.com Table of Contents Early Colonial History Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas ...................................................................................................1 By Rebecca Hofmann “Casa Real”: A Lost Church On Guam* .................................................13 By Andrea Jalandoni Magellan and San Vitores: Heroes or Madmen? ....................................25 By Donald Shuster, PhD Traditional Chamorro Farming Innovations during the Spanish and Philippine Contact Period on Northern Guam* ....................................31 By Boyd Dixon and Richard Schaefer and Todd McCurdy Islands in the Stream of Empire: Spain’s ‘Reformed’ Imperial Policy and the First Proposals to Colonize the Mariana Islands, 1565-1569 ....41 By Frank Quimby José de Quiroga y Losada: Conquest of the Marianas ...........................63 By Nicholas Goetzfridt, PhD. 19th Century Society in Agaña: Don Francisco Tudela, 1805-1856, Sargento Mayor of the Mariana Islands’ Garrison, 1841-1847, Retired on Guam, 1848-1856 ...............................................................................83 By Omaira Brunal-Perry Windfalls in Micronesia: Carolinians' environmental history in the Marianas By Rebecca Hofmann Research fellow in the project: 'Climates of Migration: -

Greening the Agriculture System: Morocco's Political Failure In

Greening the Agriculture System: Morocco’s Political Failure in Building a Sustainable Model for Development By Jihane Benamar Mentored by Dr. Harry Verhoeven A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of Honors in International Politics, Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, Spring 2018. CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 2 • THE MOROCCAN PUZZLE .................................................................................................... 5 • WHY IS AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT IMPORTANT FOR MOROCCO? .............................. 7 • WHY THE PLAN MAROC VERT? .......................................................................................... 8 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................................................ 13 • A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR “DEVELOPMENT”....................................................... 14 • ROSTOW, STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT PROGRAMS (SAPS) & THE OLD DEVELOPMENT DISCOURSE ......................................................................................................................... 19 • THE ROLE OF AGRICULTURE IN DEVELOPMENT .............................................................. 24 • SUSTAINABILITY AND THE DISCOURSE ON DEVELOPMENT & AGRICULTURE ................ -

Berbers of North Africa

Berbers of North Africa Background: The Berbers, who call themselves “imazighen” live across northern Africa and trace their roots to the indigenous pre-Arab, pre-Islamic cultures of the region. Approximately 9.5 million of them live in Morocco, about 4.3 million in Algeria, and smaller numbers in neighboring countries. The language belongs to the Afro-Asiatic language family, making it related to the ancient Egyptian language but not to modern Arabic (though Arabic is widely spoken as a second language). Most Berbers are Muslim though remnants of earlier traditions have survived as well. Berbers constitute about one-quarter of the population of Algeria. Of these Berber- speaking Algerians, about half are Kabyles, who live mostly in the mountains east of Algiers (though, as we see in the movie, many have migrated to the cities). Most Berbers, like their Arab co-nationalists, are Sunni Muslims. Throughout the 1980s, the Kabyles revolted against Algerian government policies of Arabization. Discontent and sporadic fighting has continued. To look for in the movie: - an allusion to fighting in the Berber areas - geographical/ecological features and hardships - rural to urban migration - Islamic religious and cultural practices - women’s role in Berber society A few accessible (short, clear, online) resources: “Algerian Overview: Berbers.” World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Minority Rights Group International. May 2008. <http://www.minorityrights.org/4083/algeria/berbers.html> 19 Dec. 2013. “Berber,” The Living Africa. <http://library.thinkquest.org/16645/the_people/ ethnic_berber.shtml> 19 Dec. 2013. “Q&A The Berbers.” BBC News. 12 Mar. 2004. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3509799.stm 19 Dec. -

Fa ISCIJ-1'1/~ Eyes on Morocco a Spanish Invasion Took Place in 1859 60 the First French Post Off1ce W As Opened in 1862 at Tangier

In the 1 century European powers began to cast acqu CAr.l 'fA ISCIJ-1'1/~ eyes on Morocco A Spanish invasion took place in 1859 60 The first French Post Off1ce w as opened in 1862 at Tangier. and 1n 1904 secret convent1ons provided for the partition of Until 1891 unoverprinted stamps of France were used, Types 5, Morocco between Spain and France Germany also claimed later printings of 1, 10/ 11 and 0 11 . Until 1876 numbered interests. until 1n 1911 these were g1ven up in exchange for the cancellation .. 51 06.. (large figures) was used, from 1876 date fRENCH M~occo acQUISition of part of French Congo stamps. Other offices were later opened at Casablanca•. EI Ksar.el On 30 March 1912 the Sultan of Morocco was forced to accept Kebir, Larache, Mazagan, Mogador. Rabat and Safl. Spee1al a French protectorate over all the country except for a Span1sh stamps with surcharges on French issues in cimtjmos and pesetas f.RENC ti PosT OffiCES zone of ecuon 10 the north and Tangier. which was g1ven became necessary by 1891 because of the depreciation of the S nish currency. or Black 1891-1900 Unwmk. Perf. 14x13 'h 1 A 1 Sc on Sc grn, grnsh (A) NH 12.00 3.50 8. Impart., pair 150.00 2 A 1 5c on 5c yel grn (II) (A) ('99) L U 30.00 27.50 8. Type I 30.00 24.00 3 A1 10c on 10c blk, lav #I (II) (A) n 30.00 3.25 8. Type I 37.50 20.00 b. -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

The Berber Identity: a Double Helix of Islam and War by Alvin Okoreeh

The Berber Identity: A Double Helix of Islam and War By Alvin Okoreeh Mezquita de Córdoba, Interior. Muslim Spain is characterized by a myriad of sophisticated and complex dynamics that invariably draw from a foundation rooted in an ethnically diverse populace made up of Arabs, Berbers, muwalladun, Mozarebs, Jews, and Christians. According to most scholars, the overriding theme for this period in the Iberian Peninsula is an unprecedented level of tolerance. The actual level of tolerance experienced by its inhabitants is debatable and relative to time, however, commensurate with the idea of tolerance is the premise that each of the aforementioned groups was able to leave a distinct mark on the era of Muslim dominance in Spain. The Arabs, with longstanding ties to supremacy in Damascus and Baghdad exercised authority as the conqueror and imbued al-Andalus with culture and learning until the fall of the caliphate in 1031. The Berbers were at times allies with the Arabs and Christians, were often enemies with everyone on the Iberian Peninsula, and in the times of the taifas, Almoravid and Almohad dynasties, were the rulers of al-Andalus. The muwalladun, subjugated by Arab perceptions of a dubious conversion to Islam, were mired in compulsory ineptitude under the pretense that their conversion to Islam would yield a more prosperous life. The Mozarebs and Jews, referred to as “people of the book,” experienced a wide spectrum of societal conditions ranging from prosperity to withering persecution. This paper will argue that the Berbers, by virtue of cultural assimilation and an identity forged by militant aggressiveness and religious zealotry, were the most influential ethno-religious group in Muslim Spain from the time of the initial Muslim conquest of Spain by Berber-led Umayyad forces to the last vestige of Muslim dominance in Spain during the time of the Almohads. -

Expat Guide to Casablanca

EXPAT GUIDE TO CASABLANCA SEPTEMBER 2020 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO 7 ENTRY, STAY AND RESIDENCE IN MOROCCO 13 LIVING IN CASABLANCA 19 CASABLANCA NEIGHBOURHOODS 20 RENTING YOUR PLACE 24 GENERAL SERVICES 25 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 26 STUDYING IN CASABLANCA 28 EXPAT COMMUNITIES 30 GROCERIES AND FOOD SUPPLIES 31 SHOPPING IN CASABLANCA 32 LEISURE AND WELL-BEING 34 AMUSEMENT PARKS 36 SPORT IN CASABLANCA 37 BEAUTY SALONS AND SPA 38 NIGHT LIFE, RESTAURANTS AND CAFÉS 39 ART, CINEMAS AND THATERS 40 MEDICAL TREATMENT 45 GENERAL MEDICAL NEEDS 46 MEDICAL EMERGENCY 46 PHARMACIES 46 DRIVING IN CASABLANCA 48 DRIVING LICENSE 48 CAR YOU BROUGHT FROM ABROAD 50 DRIVING LAW HIGHLIGHTS 51 CASABLANCA FINANCE CITY 53 WORKING IN CASABLANCA 59 LOCAL BANK ACCOUNTS 65 MOVING TO/WITHIN CASABLANCA 69 TRAVEL WITHIN MOROCCO 75 6 7 INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO TO INTRODUCTION 8 9 THE KINGDOM MOROCCO Morocco is one of the oldest states in the world, dating back to the 8th RELIGION AND LANGUAGE century; The Arabs called Morocco Al-Maghreb because of its location in the Islam is the religion of the State with more than far west of the Arab world, in Africa; Al-Maghreb Al-Akssa means the Farthest 99% being Muslims. There are also Christian and west. Jewish minorities who are well integrated. Under The word “Morocco” derives from the Berber “Amerruk/Amurakuc” which is its constitution, Morocco guarantees freedom of the original name of “Marrakech”. Amerruk or Amurakuc means the land of relegion. God or sacred land in Berber. -

Al-Andalus' Lessons for Contemporary European

IMMIGRATION, JUSTICE AND SOCIETY AL-ANDALUS’ LESSONS FOR CONTEMPORARY EUROPEAN MODELS OF INTEGRATION MYRIAM FRANÇOIS • BETHSABÉE SOURIS www.europeanreform.org @europeanreform Established by Margaret Thatcher, New Direction is Europe’s leading free market political foundation & publisher with offices in Brussels, London, Rome & Warsaw. New Direction is registered in Belgium as a not-for-profit organisation and is partly funded by the European Parliament. REGISTERED OFFICE: Rue du Trône, 4, 1000 Brussels, Belgium. EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Naweed Khan. www.europeanreform.org @europeanreform The European Parliament and New Direction assume no responsibility for the opinions expressed in this publication. Sole liability rests with the author. AUTHORS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 2 AL-ANDALUS’ MODEL OF INTEGRATION 8 2.1 THE IBERIAN HISTORY FROM THE MUSLIM CONQUEST TO THE RECONQUISTA 10 2.1.1 Visigoth Spain 11 2.1.2 The Muslim advance in Arabia and Northern Africa 11 2.1.3 The conquest of Spain 12 2.1.4 The unstable first years of the Umayyad dynasty 14 2.1.5 The golden ages of the Caliphate of Cordoba 14 2.1.6 The fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba 16 2.1.7 The end of Al-Andalus and the Reconquista 16 2.2 2.2 THE SOCIAL MODEL OF INTEGRATION OF AL-ANDALUS 18 2.2.1 The social and religious landscape 19 2.2.2 Controversy over the meaning of ‘convivencia’ 19 2.2.3 Protection of religious’ communities boundaries 21 2.2.4 Towards an increased integration and acculturation: The Arabization of the non-Muslim communities 22 2.2.5 The cultural impact of the convivencia 25 Myriam François Bethsabée Souris 2.2.6 Limits of coexistence 26 Dr Myiam Francois is a journalist and academic with a Bethsabée Souris is a PhD candidate in Political Science at 3 TODAY’S EUROPEAN MODELS OF MUSLIM INTEGRATION 28 focus on France and the Middle East.