Special Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Batman As a Cultural Artefact

Batman as a Cultural Artefact Kapetanović, Andrija Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zadar / Sveučilište u Zadru Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:162:723448 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zadar Institutional Repository of evaluation works Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Andrija Kapetanović Batman as a Cultural Artefact Završni rad Zadar, 2016. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Batman as a Cultural Artefact Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Andrija Kapetanović Doc. dr. Marko Lukić Zadar, 2016. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Andrija Kapetanović, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Batman as a Cultural Artefact rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. -

Congressional Record—House H2331

March 26, 2003 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H2331 postal carriers, the service responds to more There was no objection. Mr. DAVIS of Illinois. Mr. Speaker, I than 1,000 postal-related assaults and credit Mr. DUNCAN. Mr. Speaker, I yield yield myself such time as I might con- threats, 75,000 complaints of consumer mail myself such time as I may consume. sume. fraud, and it arrests 12,000 criminal suspects Mr. Speaker, it is a real honor and (Mr. DAVIS of Illinois asked and was for mail-related crimes each year. privilege for me to bring this par- given permission to revise and extend Today, my colleagues have a special oppor- ticular legislation to the floor at this his remarks.) tunity to honor the entire United States Postal time because Floyd Spence was a close, Mr. DAVIS of Illinois. Mr. Speaker, Service, by naming a postal facility after one personal friend of mine and one of the H.R. 917, which names a postal facility of their own heroes. With the passage of H.R. greatest Members this body has ever located at 1830 South Lake Drive in 825, The House of Representatives will re- seen. I had the privilege of traveling Lexington, South Carolina, after Floyd name the Moraine Valley, Illinois Post Office several different places with Congress- Spence, was introduced on February 25, the Michael J. Healy Post Office. man Spence and working with him on 2003, by the gentleman from South Finally, I would like to recognize Joan many different pieces of legislation. Carolina (Mr. WILSON). Healy, Michael’s mother, his brother David, H.R. -

16 Hours Ert! 8 Meals!

Iron Rattler; photo by Tim Baldwin Switchback; photo by S. Madonna Horcher Great White; photo by Keith Kastelic LIVING LARGE IN THE LONE STAR STATE! Our three host parks boast a total of 16 coasters, including Iron Rattler at Six Flags Fiesta Texas, Switch- Photo by Tim Baldwin back at ZDT’s Amuse- ment Park and Steel Eel at SeaWorld. 16 HOURS ERT! 8 MEALS! •An ERT session that includes ALL rides at Six Flags Fiesta Texas •ACE’s annual banquet, with keynote speaker John Duffey, president and CEO, Six Flags •Midway Olympics and Rubber Ducky Regatta •Exclusive access to two Fright Fest haunted houses at Six Flags Fiesta Texas REGISTRATION Postmarked by May 27, 2017 NOT A MEMBER? JOIN TODAY! or completed online by June 5, 2017. You’ll enjoy member rates when you join today online or by mail. No registrations accepted after June 5, 2017. There is no on-site registration. Memberships in the world’s largest ride enthusiast organization start at $20. Visit aceonline.org/joinace to learn more. ACE MEMBERS $263 ACE MEMBERS 3-11 $237 SIX FLAGS SEASON PASS DISCOUNT NON-MEMBERS $329 Your valid 2017 Six Flags season pass will NON-MEMBERS 3-11 $296 save you $70 on your registration fee! REGISTER ONLINE ZDT’S EXTREME PASSES Video contest entries should be mailed Convenient, secure online registration is Attendees will receive ZDT’s Extreme to Chris Smilek, 619 Washington Cross- available at my.ACEonline.org. Passes, for unlimited access to all attrac- ing, East Stroudsburg, PA, 18301-9812, tions on Thursday, June 22. -

Man of the House

Walkthrough - - (7.30AM) breakfast talk with mom, for earn some points. - (8.30AM) Talk with Sis (Ashley) twice, and open new option. - For now MC only need talk with Veronica in the Kitchen (9.00 - 10.00AM) and open new option. - In the beggin MC need go in his Room and in the computer and have Online Course, do it till have the message that MC –have mastered completely - (8.00-12.00AM) - MC need go in the pizzeria and Work (12.00 -15.00AM) – doing this, MC can open new options, and get some itens. - (15.00PM) Teaching Sis in Her Bedroom, twice. - (18.00PM) Dinner with everyone. - (19.00) Talk with Mom in the kitchen, for earn some points. - (19.00 – 19.30PM) See movies with Sis. - (21,00PM) MC giving for Mom the -rub foot-, after –Try to move- (MC need give her some Wine) -Buy in the Supermarket - - - (22.00PM) MC need give Goodnight for Sis (Ashley) - (6.00AM) Go to the rooftop, see and talk with Mom. - - The Rooftop - - Advice: Walking or travel with bus, taxi or even going with Veronica’s car, is a random event but MC can find some itens and some advertising that open Pizzeria, Casino and maybe others location (in the next version). - And for open Health Club, MC need talk with Mom in the rooftop (6.00AM) - In the morning new event (7.00AM) MC need sleep and wake up at 7.00Am (before sleep need heard the phone in the Mom's bedroom, 22.00PM Mom and Aunt talking) - - Ashley - (8.30AM) - Breakfast - (15.00PM) - Teaching (Twice, till options are open) - (19.00PM) - See movies (When Horror movie are open, new option in the night) (19.30PM when MC talk with Mom) - (21.00PM) - Bathroom (New scenes with Sis) – You can alternate with Mom’s scenes – one day Sis, another Mom. -

Swepston and Okey Separation Work Well Together

APRIL 24, 2012 Volume 7 : Issue 16 In this issue... • Triple Turn Classic, page 11 • UBR, page 17 • Appleatchee Futurity, page 23 •Pro Rodeos, page 26 ffastast hhorses,orses, ffastast nnewsews • Tri-K Barrels, page 30 Published Weekly Online at www.BarrelRacingReport.com - Since 2007 Swepston and Okey Separation Work Well Together Lucky Dog $11,750 Added Futurity/Derby/Open 4D Dash For Cash April 20-22, 2012, Starkville, MS First Down Dash si 114 si 105 Futurity Average First Prize Rose 1 Okey Separation, Kinsley Swepston, 16.251, $1,374.72 Okey Dokey Dale si 98 08 brn. g. Okey Dokey Dale-Separate Dash, Separatist si 108 2 TKayleesBlushingBug, Donnie Reece, Diane Reece, 16.358, $1,145.60 Zevi 3 Flits Western Trophy, Gina Cates, 16.369, $973.76 Okeydokey Baby tb 4 Shez Chiseled, Talmadge Green, Kris Suard, 16.379, $744.64 si 101 Mayolas Doll 5 Dr Brenda, Tracey Goodman, Debbie Hertz, 16.439, $572.80 Okey Separation si 92 6 Blare, Marne Loosenort, Danny Kingins, 16.457, $400.99 7 Uknowuenvyme, Carrie Thompson, 16.492, $286.40 2008 Brown Gelding 8 PT Nonstop Perks, Marne Loosenort, Danny Kingins, 16.535, Chicks Beduino $229.12 Separatist si 104 si 101 Seperate Ways Futurity 1st Go Separate Dash si 92 1D 1 TKayleesBlushingBug, Donnie Reece, Diane Reece, 15.919, si 90 $1,301.04 First Down Dash 08 s. f. Red Bug From Hell-My Go Go Cash, Cash Easy Acomodash si 105 2 VF A Smokin Duck, Andy Wininger, James Evan Garrett, 16.084, si 99 Accomodations $859.20 si 85 3 Famous Streak, Kebo Almond, FC Ranch, 16.119, $730.20 4 Okey Separation, Kinsley Swepston, -

The Official Magazine of American Coaster Enthusiasts Rc! 127

FALL 2013 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF AMERICAN COASTER ENTHUSIASTS RC! 127 VOLUME XXXV, ISSUE 1 $8 AmericanCoasterEnthusiasts.org ROLLERCOASTER! 127 • FALL 2013 Editor: Tim Baldwin THE BACK SEAT Managing Editor: Jeffrey Seifert uthor Mike Thompson had the enviable task of covering this year’s Photo Editor: Tim Baldwin Coaster Con for this issue. It must have been not only a delight to Associate Editors: Acapture an extraordinary convention in words, but also a source of Bill Linkenheimer III, Elaine Linkenheimer, pride as it is occurred in his very region. However, what a challenge for Jan Rush, Lisa Scheinin him to try to capture a week that seemed to surpass mere words into an ROLLERCOASTER! (ISSN 0896-7261) is published quarterly by American article that conveyed the amazing experience of Coaster Con XXXVI. Coaster Enthusiasts Worldwide, Inc., a non-profit organization, at 1100- I remember a week filled with a level of hospitality taken to a whole H Brandywine Blvd., Zanesville, OH 43701. new level, special perks in terms of activities and tours, and quite Subscription: $32.00 for four issues ($37.00 Canada and Mexico, $47 simply…perfect weather. The fact that each park had its own charm and elsewhere). Periodicals postage paid at Zanesville, OH, and an addition- character made it a magnificent week — one that truly exemplifies what al mailing office. Coaster Con is all about and why many people make it the can’t-miss event of the year. Back issues: RCReride.com and click on back issues. Recent discussion among ROLLERCOASTER! subscriptions are part of the membership benefits for our ROLLERCOASTER! staff American Coaster Enthusiasts. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Cedar Point Welcomes 2016 Golden Ticket Awards Ohio Park and Resort Host Event for Second Time SANDUSKY, Ohio — the First Chapter in Cedar and Beyond

2016 GOLDEN TICKET AWARDS V.I.P. BEST OF THE BEST! TM & ©2016 Amusement Today, Inc. September 2016 | Vol. 20 • Issue 6.2 www.goldenticketawards.com Cedar Point welcomes 2016 Golden Ticket Awards Ohio park and resort host event for second time SANDUSKY, Ohio — The first chapter in Cedar and beyond. Point's long history was written in 1870, when a bath- America’s top-rated park first hosted the Gold- ing beach opened on the peninsula at a time when en Ticket Awards in 2004, well before the ceremony such recreation was finding popularity with lake island continued to grow into the “Networking Event of the areas. Known for an abundance of cedar trees, the Year.” At that time, the awards were given out be- resort took its name from the region's natural beauty. low the final curve of the award-winning Millennium It would have been impossible for owners at the time Force. For 2016, the event offered a full weekend of to ever envision the world’s largest ride park. Today activities, including behind-the-scenes tours of the the resort has evolved into a funseeker’s dream with park, dinners and receptions, networking opportuni- a total of 71 rides, including one of the most impres- ties, ride time and a Jet Express excursion around sive lineups of roller coasters on the planet. the resort peninsula benefiting the National Roller Tourism became a booming business with the Coaster Museum and Archives. help of steamships and railroad lines. The original Amusement Today asked Vice President and bathhouse, beer garden and dance floor soon were General Manager Jason McClure what he was per- joined by hotels, picnic areas, baseball diamonds and sonally looking forward to most about hosting the a Grand Pavilion that hosted musical concerts and in- event. -

San Diego Health & Exercise Survey

THIS SURVEY SHOULD BE COMPLETELY FILLED OUT BY THE FOLLOWING PERSON, WHO MUST BE I' AT LEAST 18 YEARS OLD: D The lady of the house. If the lady of D The man of the house. If the man of the house is not available, then the the house is not available, then the man of the house should fill it out. lady of the house should 'fill it out. o Check here if you want a free 2 week pass to Family Fitness Center. Please read each question carefully and answer it to the best of your ability. Do not spend too much time on any question. Your answers will be kept in strictest confidence. SAN DIEGO HEALTH & EXERCISE SURVEY 1. How is your health? (PLEASE CHECK ONE) VERY GOOD_l GOOD 2 AVERAGE _3 POOR _4 VERY POOR_5 2. Do you need to limit your physical activity because of an illness, NO 1 injury or handicap? YES, BECAUSE OF TEMPORARY ILLNESS _ 2 (CHECK ONE) YES, BECAUSE OF LONG-TERM ILLNESS _ 3 YES, BECAUSE OF TEMPORARY INJURY _ 4 YES, BECAUSE OF LONG-TERM INJURY . OR HANDICAP. _ 5 3. Are you being treated by a doctor for any medical condition? NO _1 If yes, please explain _ YES _2 4. Have either of your parents ever had a heart attack or stroke before NO 1 they were 55 years old? YES _2 DON'T KNOW _3 5. How often do you eat the following foods? (MARK ONE NUMBER FOR EACH ITEM) Never or Several Few Times About Once Times Few Times Almost a Year a Month a Month a Week ~ 1. -

Congressional Record-·House

1900. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-·HOUSE. 189 By Mr. HOFFECKER: A bill (H. R.12507) granting an increase By Mr. ROBINSON of Indiana: Petition of Advance Grange, of pension to Ezekiel Dawson-to the Committee on Invalid Pen No. 2100, Patrons of Husbandry, of Fremont, Ind., favoring pure sions. food legislation-to the Committee on Agriculture. By Mr. RANSDELL: A bill (H. R. 12508) for the relief of John By Mr. RYAN of New York: Petition of Rev. George B. New McDonnell-to the Committee on Military Affairs. comb and others, of Buffalo, N. Y., in favor of the anti-polygamy By Mr. KLEBERG: A bill (H. R. 12509) for the relief of Maria. amendment to the Constitution-to the Committee on the Judi Thornton, residuary legatee of Richard Miller, deceased-to the ciary. Committee on War Claims. By Mr. SHACKLEFORD: Petition of the estate of John W. Livesay, deceased, of Missouri, for reference of war claim to the Court of Claims-to the Committee on War Claims. PETITIONS, ETC. By Mr. SIBL.EY: Petitions of druggists of Warren County, Pa., Under clause 1 of Rule XXII, the following petitions and papers for the repeal of the special tax on proprietary medicines-to the were laid on the Clerk's desk and referred as follows: Committee on Ways and Means. By Mr. ACHESON: Petition of J. D. Moffat and other citizens Also, petition of citizens of Warren, Pa., in favor of the anti of Washington County, Pa., in favor of an amendment to the polygamy amendment to the Constitution-to the Committee on Constitution against polygamy-to the Committee on the Judi the Judiciary. -

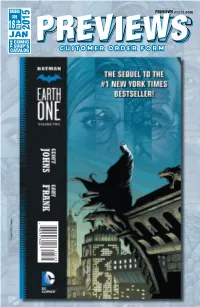

CUSTOMER ORDER FORM (Net)

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 JAN 2015 JAN COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jan15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:14:17 PM Available only from your local comic shop! STAR WARS: “THE FORCE POSTER” BLACK T-SHIRT Preorder now! BIG HERO 6: GUARDIANS OF THE DC HEROES: BATMAN “BAYMAX BEFORE GALAXY: “HANG ON, 75TH ANNIVERSARY & AFTER” LIGHT ROCKET & GROOT!” SYMBOL PX BLACK BLUE T-SHIRT T-SHIRT T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 01 Jan15 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:06:36 PM FRANKENSTEIN CHRONONAUTS #1 UNDERGROUND #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: EARTH ONE VOLUME 2 HC DC COMICS PASTAWAYS #1 DESCENDER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS IMAGE COMICS JEM AND THE HOLOGRAMS #1 IDW PUBLISHING CONVERGENCE #0 ALL-NEW DC COMICS HAWKEYE #1 MARVEL COMICS Jan15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 2:59:43 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS God Is Dead Volume 4 TP (MR) l AVATAR PRESS The Con Job #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Bill & Ted’s Most Triumphant Return #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 3 #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS/ARCHAIA PRESS Project Superpowers: Blackcross #1 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Angry Youth Comix HC (MR) l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 Hellbreak #1 (MR) l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: The Ninth Doctor #1 l TITAN COMICS Penguins of Madagascar Volume 1 TP l TITAN COMICS 1 Nemo: River of Ghosts HC (MR) l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Ninjak #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT BOOKS The Art of John Avon: Journeys To Somewhere Else HC l ART BOOKS Marvel Avengers: Ultimate Character Guide Updated & Expanded l COMICS DC Super Heroes: My First Book Of Girl Power Board Book l COMICS MAGAZINES Marvel Chess Collection Special #3: Star-Lord & Thanos l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #1 l COMICS Alter Ego #132 l COMICS Back Issue #80 l COMICS 2 The Walking Dead Magazine #12 (MR) l MOVIE/TV TRADING CARDS Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Roxy Music Live at the Apollo Mp3, Flac, Wma

Roxy Music Live At The Apollo mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Live At The Apollo Country: South Korea Released: 2002 Style: New Wave MP3 version RAR size: 1146 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1645 mb WMA version RAR size: 1331 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 409 Other Formats: DMF AC3 RA AU MPC MP1 WAV Tracklist 1 Re-Make / Re-Model 2 Street Life 3 Ladytron 4 While My Heart Is Still Beating 5 Out Of The Blue 6 A Song For Europe 7 My Only Love 8 In Every Dream Home A Heartache 9 Oh Yeah! 10 Both Ends Burning 11 Tara 12 Band Introductions 13 Mother Of Pearl 14 Avalon 15 Dance Away 16 Jealous Guy 17 Editions Of You 18 Virginia Plain 19 Love Is The Drug 20 Do The Strand 21 For Your Pleasure 22 Exclusive Documentary Notes Recorded live @ The Apollo Theater, London, 2001. Tot. time 125 min. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 8 809092 445063 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Live At The Apollo Roxy (DVD-V, Warner Music 0927-45214-2 0927-45214-2 Germany 2002 Music Multichannel, PAL, Vision DTS) Live At The Apollo Roxy STAR 226-9 (Blu-ray-R, Album, Starlight Film STAR 226-9 Russia 2011 Music Unofficial) Live At The Apollo Roxy Warner Music 4670001546003 (DVD, Multichannel, 4670001546003 Russia 2002 Music Vision, Никитин PAL, DTS) Warner Music Live At The Apollo Roxy Vision, Фирма 4670001546003 (DVD, Multichannel, 4670001546003 Russia 2002 Music Грамзаписи PAL) Никитин Live At The Apollo Roxy (DVD-V, Warner Music USA & 0087WIDVD 0087WIDVD 2002 Music Multichannel, NTSC, Vision Canada DTS) Related Music albums to Live At The Apollo by Roxy Music Roxy Music - Concerto Roxy Music - Heart Still Beating Roxy Music - MP3 Collection Roxy Music - Viva! Roxy Music Bryan Ferry + Roxy Music - The Platinum Collection Roxy Music - Viva! Roxy Music - The Live Roxy Music Album Toots & The Maytals - Sailin' On - Live At The Roxy Theater LA 1975 Roxy Music - Inside Roxy Music 1972-1974 Yello - The Yello Video Show - Live At The Roxy NY Dec 83 Roxy Music - Virginia Plain / Street Life.