Propagating, Evanescent, and Complex Wavenumber Guided Waves in High-Performance Composites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Linkage Between Planck's Quantum and Maxwell's Equations

The Finnish Society for Natural Philosophy 25 years, K.V. Laurikainen Honorary Symposium, Helsinki 11.-12.11.2013 On the Linkage between Planck's Quantum and Maxwell's Equations Tuomo Suntola Physics Foundations Society, www.physicsfoundations.org Abstract The concept of quantum is one of the key elements of the foundations in modern physics. The term quantum is primarily identified as a discrete amount of something. In the early 20th century, the concept of quantum was needed to explain Max Planck’s blackbody radiation law which suggested that the elec- tromagnetic radiation emitted by atomic oscillators at the surfaces of a blackbody cavity appears as dis- crete packets with the energy proportional to the frequency of the radiation in the packet. The derivation of Planck’s equation from Maxwell’s equations shows quantizing as a property of the emission/absorption process rather than an intrinsic property of radiation; the Planck constant becomes linked to primary electrical constants allowing a unified expression of the energies of mass objects and electromagnetic radiation thereby offering a novel insight into the wave nature of matter. From discrete atoms to a quantum of radiation Continuity or discontinuity of matter has been seen as a fundamental question since antiquity. Aristotle saw perfection in continuity and opposed Democritus’s ideas of indivisible atoms. First evidences of atoms and molecules were obtained in chemistry as multiple proportions of elements in chemical reac- tions by the end of the 18th and in the early 19th centuries. For physicist, the idea of atoms emerged for more than half a century later, most concretely in statistical thermodynamics and kinetic gas theory that converted the mole-based considerations of chemists into molecule-based considerations based on con- servation laws and probabilities. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Turbulence Examined in the Frequency-Wavenumber Domain*

Turbulence examined in the frequency-wavenumber domain∗ Andrew J. Morten Department of Physics University of Michigan Supported by funding from: National Science Foundation and Office of Naval Research ∗ Arbic et al. JPO 2012; Arbic et al. in review; Morten et al. papers in preparation Andrew J. Morten LOM 2013, Ann Arbor, MI Collaborators • University of Michigan Brian Arbic, Charlie Doering • MIT Glenn Flierl • University of Brest, and The University of Texas at Austin Robert Scott Andrew J. Morten LOM 2013, Ann Arbor, MI Outline of talk Part I{Motivation (research led by Brian Arbic) • Frequency-wavenumber analysis: {Idealized Quasi-geostrophic (QG) turbulence model. {High-resolution ocean general circulation model (HYCOM)∗: {AVISO gridded satellite altimeter data. ∗We used NLOM in Arbic et al. (2012) Part II-Research led by Andrew Morten • Derivation and interpretation of spectral transfers used above. • Frequency-domain analysis in two-dimensional turbulence. • Theoretical prediction for frequency spectra and spectral transfers due to the effects of \sweeping." {moving beyond a zeroth order approximation. Andrew J. Morten LOM 2013, Ann Arbor, MI Motivation: Intrinsic oceanic variability • Interested in quantifying the contributions of intrinsic nonlinearities in oceanic dynamics to oceanic frequency spectra. • Penduff et al. 2011: Interannual SSH variance in ocean models with interannual atmospheric forcing is comparable to variance in high resolution (eddying) ocean models with no interannual atmospheric forcing. • Might this eddy-driven low-frequency variability be connected to the well-known inverse cascade to low wavenumbers (e.g. Fjortoft 1953)? • A separate motivation is simply that transfers in mixed ! − k space provide a useful diagnostic. Andrew J. -

Variable Planck's Constant

Variable Planck’s Constant: Treated As A Dynamical Field And Path Integral Rand Dannenberg Ventura College, Physics and Astronomy Department, Ventura CA [email protected] [email protected] January 28, 2021 Abstract. The constant ħ is elevated to a dynamical field, coupling to other fields, and itself, through the Lagrangian density derivative terms. The spatial and temporal dependence of ħ falls directly out of the field equations themselves. Three solutions are found: a free field with a tadpole term; a standing-wave non-propagating mode; a non-oscillating non-propagating mode. The first two could be quantized. The third corresponds to a zero-momentum classical field that naturally decays spatially to a constant with no ad-hoc terms added to the Lagrangian. An attempt is made to calibrate the constants in the third solution based on experimental data. The three fields are referred to as actons. It is tentatively concluded that the acton origin coincides with a massive body, or point of infinite density, though is not mass dependent. An expression for the positional dependence of Planck’s constant is derived from a field theory in this work that matches in functional form that of one derived from considerations of Local Position Invariance violation in GR in another paper by this author. Astrophysical and Cosmological interpretations are provided. A derivation is shown for how the integrand in the path integral exponent becomes Lc/ħ(r), where Lc is the classical action. The path that makes stationary the integral in the exponent is termed the “dominant” path, and deviates from the classical path systematically due to the position dependence of ħ. -

Variable Planck's Constant

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 29 January 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202101.0612.v1 Variable Planck’s Constant: Treated As A Dynamical Field And Path Integral Rand Dannenberg Ventura College, Physics and Astronomy Department, Ventura CA [email protected] Abstract. The constant ħ is elevated to a dynamical field, coupling to other fields, and itself, through the Lagrangian density derivative terms. The spatial and temporal dependence of ħ falls directly out of the field equations themselves. Three solutions are found: a free field with a tadpole term; a standing-wave non-propagating mode; a non-oscillating non-propagating mode. The first two could be quantized. The third corresponds to a zero-momentum classical field that naturally decays spatially to a constant with no ad-hoc terms added to the Lagrangian. An attempt is made to calibrate the constants in the third solution based on experimental data. The three fields are referred to as actons. It is tentatively concluded that the acton origin coincides with a massive body, or point of infinite density, though is not mass dependent. An expression for the positional dependence of Planck’s constant is derived from a field theory in this work that matches in functional form that of one derived from considerations of Local Position Invariance violation in GR in another paper by this author. Astrophysical and Cosmological interpretations are provided. A derivation is shown for how the integrand in the path integral exponent becomes Lc/ħ(r), where Lc is the classical action. The path that makes stationary the integral in the exponent is termed the “dominant” path, and deviates from the classical path systematically due to the position dependence of ħ. -

The Principle of Relativity and the De Broglie Relation Abstract

The principle of relativity and the De Broglie relation Julio G¨u´emez∗ Department of Applied Physics, Faculty of Sciences, University of Cantabria, Av. de Los Castros, 39005 Santander, Spain Manuel Fiolhaisy Physics Department and CFisUC, University of Coimbra, 3004-516 Coimbra, Portugal Luis A. Fern´andezz Department of Mathematics, Statistics and Computation, Faculty of Sciences, University of Cantabria, Av. de Los Castros, 39005 Santander, Spain (Dated: February 5, 2016) Abstract The De Broglie relation is revisited in connection with an ab initio relativistic description of particles and waves, which was the same treatment that historically led to that famous relation. In the same context of the Minkowski four-vectors formalism, we also discuss the phase and the group velocity of a matter wave, explicitly showing that, under a Lorentz transformation, both transform as ordinary velocities. We show that such a transformation rule is a necessary condition for the covariance of the De Broglie relation, and stress the pedagogical value of the Einstein-Minkowski- Lorentz relativistic context in the presentation of the De Broglie relation. 1 I. INTRODUCTION The motivation for this paper is to emphasize the advantage of discussing the De Broglie relation in the framework of special relativity, formulated with Minkowski's four-vectors, as actually was done by De Broglie himself.1 The De Broglie relation, usually written as h λ = ; (1) p which introduces the concept of a wavelength λ, for a \material wave" associated with a massive particle (such as an electron), with linear momentum p and h being Planck's constant. Equation (1) is typically presented in the first or the second semester of a physics major, in a curricular unit of introduction to modern physics. -

ATMS 310 Rossby Waves Properties of Waves in the Atmosphere Waves

ATMS 310 Rossby Waves Properties of Waves in the Atmosphere Waves – Oscillations in field variables that propagate in space and time. There are several aspects of waves that we can use to characterize their nature: 1) Period – The amount of time it takes to complete one oscillation of the wave\ 2) Wavelength (λ) – Distance between two peaks of troughs 3) Amplitude – The distance between the peak and the trough of the wave 4) Phase – Where the wave is in a cycle of amplitude change For a 1-D wave moving in the x-direction, the phase is defined by: φ ),( = −υtkxtx − α (1) 2π where φ is the phase, k is the wave number = , υ = frequency of oscillation (s-1), and λ α = constant determined by the initial conditions. If the observer is moving at the phase υ speed of the wave ( c ≡ ), then the phase of the wave is constant. k For simplification purposes, we will only deal with linear sinusoidal wave motions. Dispersive vs. Non-dispersive Waves When describing the velocity of waves, a distinction must be made between the group velocity and the phase speed. The group velocity is the velocity at which the observable disturbance (energy of the wave) moves with time. The phase speed of the wave (as given above) is how fast the constant phase portion of the wave moves. A dispersive wave is one in which the pattern of the wave changes with time. In dispersive waves, the group velocity is usually different than the phase speed. A non- dispersive wave is one in which the patterns of the wave do not change with time as the wave propagates (“rigid” wave). -

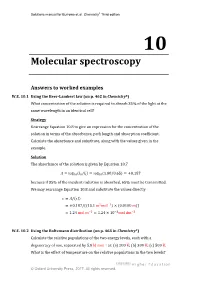

Molecular Spectroscopy

Solutions manual for Burrows et.al. Chemistry3 Third edition 10 Molecular spectroscopy Answers to worked examples W.E. 10.1 Using the Beer-Lambert law (on p. 462 in Chemistry3) What concentration of the solution is required to absorb 35% of the light at the same wavelength in an identical cell? Strategy Rearrange Equation 10.8 to give an expression for the concentration of the solution in terms of the absorbance, path length and absorption coefficient. Calculate the absorbance and substitute, along with the values given in the example. Solution The absorbance of the solution is given by Equation 10.7 퐴 = log10(퐼0/퐼t) = log10(1.00/0.65) = +0.187 because if 35% of the incident radiation is absorbed, 65% must be transmitted. We may rearrange Equation 10.8 and substitute the values directly 푐 = 퐴/(휖푙) = +0.187/{(15.1 m2mol−1) × (0.0100 m)} = 1.24 mol m−3 = 1.24 × 10−3mol dm−3 W.E. 10.2 Using the Boltzmann distribution (on p. 463 in Chemistry3) Calculate the relative populations of the two energy levels, each with a degeneracy of one, separated by 5.0 kJ mol1 at: (a) 200 K; (b) 300 K; (c) 500 K. What is the effect of temperature on the relative populations in the two levels? H i g h e r E d u c a t i o n © Oxford University Press, 2017. All rights reserved. Solutions manual for Burrows et.al. Chemistry3 Third edition Strategy Use Equation 10.9, which shows how the Boltzmann distribution affects the relative populations of two energy levels. -

Λ = H/P (De Broglie’S Hypothesis) Where P Is the Momentum and H Is the Same Planck’S Constant

PHYSICS 2800 – 2nd TERM Outline Notes Section 1. Basics of Quantum Physics The approach here will be somewhat historical, emphasizing the main developments that are useful for the applications coming later for materials science. We begin with a brief (but incomplete history), just to put things into context. 1.1 Some historical background (exploring “wave” versus “particle” ideas) Before ~ 1800: Matter behaves as if continuous (seems to be infinitely divisible) Light is particle-like (shadows have sharp edges; lenses described using ray tracing). From ~ 1800 to ~ early1900s: Matter consists of lots of particles - measurement of e/m ratio for electron (JJ Thomson 1897) - measurement of e for electron (Millikan 1909; he deduced mass me was much smaller than matom ) - discovery of the nucleus (Rutherford 1913; he found that α particles could scatter at large angles from metal foil). Light is a wave - coherent light from two sources can interfere (Young 1801). Just after ~ 1900: Light is a particle (maybe)? - photoelectric effect (explained by Einstein 1905 assuming light consists of particles) - Compton effect (Compton 1923; he explained scattering of X-rays from electrons in terms of collisions with particles of light; needed relativity). Matter is a wave (maybe)? - matter has wavelike properties and can exhibit interference effects (de Broglie wave hypothesis 1923) - the Bohr atom (Bohr 1923: he developed a model for the H-atom with only certain stable states allowed → ideas of “quantization”) - interference effects shown for electrons and neutrons (now the basis of major experimental techniques). The present time: Both matter and light can have both particle and wavelike properties. -

Chapter 2 Nature of Radiation

CHAPTER 2 NATURE OF RADIATION 2.1 Remote Sensing of Radiation Energy transfer from one place to another is accomplished by any one of three processes. Conduction is the transfer of kinetic energy of atoms or molecules (heat) by contact among molecules travelling at varying speeds. Convection is the physical displacement of matter in gases or liquids. Radiation is the process whereby energy is transferred across space without the necessity of transfer medium (in contrast with conduction and convection). The observation of a target by a device separated by some distance is the act of remote sensing (for example ears sensing acoustic waves are remote sensors). Remote sensing with satellites for meteorological research has been largely confined to passive detection of radiation emanating from the earth/atmosphere system. All satellite remote sensing systems involve the measurement of electromagnetic radiation. Electromagnetic radiation has the properties of both waves and discrete particles, although the two are never manifest simultaneously. 2.2 Basic Units All forms of electromagnetic radiation travel in a vacuum at the same velocity, which is approximately 3 x 10**10 cm/sec and is denoted by the letter c. Electromagnetic radiation is usually quantified according to its wave-like properties, which include intensity and wavelength. For many applications it is sufficient to consider electromagnetic waves as being a continuous train of sinusoidal shapes. If radiation has only one colour, it is said to be monochromatic. The colour of any particular kind of radiation is designated by its frequency, which is the number of waves passing a given point in one second and is represented by the letter f (with units of cycles/sec or Hertz). -

(Rees Chapters 2 and 3) Review of E and B the Electric Field E Is a Vector

ELECTROMAGNETISM SUMMARY (Rees Chapters 2 and 3) Review of E and B The electric field E is a vector function. E q q o If we place a second test charged qo in the electric field of the charge q, the two spheres will repel each other. The strength of the radial force Fr is proportional to the product of the charges and inversely proportional to the distance between them squared. 1 qoq Fr = Coulomb's Law 4πεo r2 -12 where εo is the electric permittivity (8.85 x 10 F/m) . The radial component of the electric field is the force divided by the strength of the test charge qo. 1 q force ML Er = - 4πεo r2 charge T2Q The magnetic field B is also a vector function. Magnetic fields are generated by charges in motion. For example, a current traveling through a wire will produce a magnetic field. A charge moving through a uniform magnetic field will experience a force that is proportional to the component of velocity perpendicular to the magnetic field. The direction of the force is perpendicular to both v and B. X X X X X X X X XB X X X X X X X X X qo X X X vX X X X X X X X X X X F X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X F = qov ⊗ B The particle will move along a curved path that balances the inward-directed force F⊥ and the € outward-directed centrifugal force which, of course, depends on the mass of the particle. -

Simple Derivation of Electromagnetic Waves from Maxwell's Equations

Simple Derivation of Electromagnetic Waves from Maxwell’s Equations By Lynda Williams, Santa Rosa Junior College Physics Department Assume that the electric and magnetic fields are constrained to the y and z directions, respectfully, and that they are both functions of only x and t. This will result in a linearly polarized plane wave travelling in the x direction at the speed of light c. Ext( , ) Extj ( , )ˆ and Bxt( , ) Bxtk ( , ) ˆ We will derive the wave equation from Maxwell’s Equations in free space where I and Q are both zero. EB 0 0 BE EB με tt00 iˆˆ j kˆ E Start with Faraday’s Law. Take the curl of the E field: E( x , t )ˆ j = kˆ x y z x 0E ( x , t ) 0 EB Equating magnitudes in Faraday’s Law: (1) xt This means that the spatial variation of the electric field gives rise to a time-varying magnetic field, and visa-versa. In a similar fashion we derive a second equation from Ampere-Maxwell’s Law: iˆˆ j kˆ BBE Take the curl of B: B( x , t ) kˆ = ˆ j (2) x y z x x00 t 0 0B ( x , t ) This means that the spatial variation of the magnetic field gives rise to a time-varying electric field, and visa-versa. Take the partial derivative of equation (1) with respect to x and combining the results from (2): 22EBBEE 22 = 0 0 0 0 x x t t x t t t 22EE (3) xt2200 22BB In a similar manner, we can derive a second equation for the magnetic field: (4) xt2200 Both equations (3) and (4) have the form of the general wave equation for a wave (,)xt traveling in 221 the x direction with speed v: .