Participatory Budgeting in Argentina. an Analysis of the Results in Political-Institutional Matters and Citizen Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Potro: Rodrigo Bueno, Breve Biografía 49 Yo Soy Gilda: Miriam Bianchi, Breve Biografía 59

Las representaciones sociales de los artistas populares tras su desaparición física Filipo, Agustina Legajo n° 23133/2 Télefono: (221) 15-6425447 [email protected] Acosta, María Florencia Legajo n° 23166/1 Telefono: (221)15-5409988 [email protected] “Las representaciones sociales de los artistas populares tras su desaparición física” Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social Director: Lic. Aramendi, Rodrigo Junio 2018 La Plata Agradecimientos A mamá, porque desde el amor y la experiencia supo acompañarme en este camino mejor que nadie. A papá, que estuvo conmigo en todo momento y lugar. A Fran y a toda mi familia, por el apoyo incansable. A Pedro, por ser mi mano derecha y compañero. A Nico, por ser el mejor amigo que este proceso pudo haberme regalado. Y a mis amigas, que a pesar de todo siempre me ofrecieron su abrazo. Agustina A mi papá y a mi mamá por alentarme a ser más y a nunca bajar los brazos. A Nacho por enseñarme a ser mejor persona con todo su amor. A mis abuelas, Reneé y Lidia, que son lo mejor de la vida. A Javi por estar en todo momento a mi lado con las palabras justas. A la China, por ser incondicional en todo momento. A mis amigas que me acompañan en cada paso. Florencia Las representaciones sociales de los artistas populares tras su desaparición física Resumen Esta investigación se propuso indagar en las representaciones sociales de los con- sumidores de entre 25 y 45 años de la ciudad de La Plata sobre los artistas populares Rodrigo El Potro Bueno y Miriam Alejandra Bianchi Gilda en la actualidad, con el fin de analizar si la desaparición física produce transformaciones en las representa- ciones sociales sobre los artistas y cómo afecta la muerte en la construcción de sen- tidos sobre ellos. -

Documento Completo Descargar Archivo

Fabiana Andrea Carbonari Los edificios de valor patrimonial, escenarios de ideales de la vida pública platense ANCL El caso del Pasaje Dardo Rocha1 AJES 45 T ram[ p ]as Fabiana Andrea Carbonari El edificio del Pasaje Dardo Ro- platenses emparentándolo con cha constituye uno de los ejem- la gran arquitectura de la ciudad. Docente Facultad de Arquitectura y Urba- plos más significativos del patri- Abordar la comprensión total de nismo de la UNLP. Investigadora UI Nº 7 IDEHAB- FAU-UNLP. Secretaria Técnica monio construido de la ciudad este “edificio de precisa y poten- de la Carrera de Especialización en Con- de La Plata. A la valoración his- te inserción urbana”2, implica servación y Restauración del Patrimo- tórica se agregan su carácter de enmarcarlo en el contexto céntri- nio Urbano, Arquitectónico y Artístico. Representante adjunta de la FAU en CO- unicidad estilístico-morfológico co de la manzana comprendida DESI (Comisión del Sitio).Representante dentro de la heterogeneidad ur- por la Avenida 7 y las calles 6, de la UNLP en la Comisión de Educación bana, su particular inserción en 49 y 50 de la ciudad de La Pla- y Difusión de CODESi (Comisión del Si- tio).Coordinadora del Proyecto “Patrimo- un espacio singular y su valor ta, en una posición estratégica nio y Educación Preuniversitaria”- Prose- simbólico en tanto hito presente frente a la Plaza San Martín per- cretaría de Asuntos Académicos-UNLP. en la memoria de los habitantes teneciente al Eje Cívico Adminis- Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social • Universidad Nacional de La Plata Fabiana Andrea Carbonari El caso del Pasaje Dardo Rocha tes en el campo disciplinar arqui- tectónico, el mero pragmatismo y su presencia en el imaginario local, son algunos de los aspec- tos a tratar. -

Understanding the Tonada Cordobesa from an Acoustic

UNDERSTANDING THE TONADA CORDOBESA FROM AN ACOUSTIC, PERCEPTUAL AND SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE by María Laura Lenardón B.A., TESOL, Universidad Nacional de Río Cuarto, 2000 M.A., Spanish Translation, Kent State University, 2003 M.A., Hispanic Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by María Laura Lenardón It was defended on April 21, 2017 and approved by Dr. Shelome Gooden, Associate Professor of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Susana de los Heros, Professor of Hispanic Studies, University of Rhode Island Dr. Matthew Kanwit, Assistant Professor of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Scott F. Kiesling, Professor of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by María Laura Lenardón 2017 iii UNDERSTANDING THE TONADA CORDOBESA FROM AN ACOUSTIC, PERCEPTUAL AND SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE María Laura Lenardón, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 The goal of this dissertation is to gain a better understanding of a non-standard form of pretonic vowel lengthening or the tonada cordobesa, in Cordobese Spanish, an understudied dialect in Argentina. This phenomenon is analyzed in two different but complementary studies and perspectives, each of which contributes to a better understanding of the sociolinguistic factors that constrain its variation, as well as the social meanings of this feature in Argentina. Study 1 investigates whether position in the intonational phrase (IP), vowel concordance, and social class and gender condition pretonic vowel lengthening from informal conversations with native speakers (n=20). -

Asociación Del Fútbol Argentino

Asociación del Fútbol Argentino Gerencia del Registro de Jugadores Boletín Complementario Nº 1/2020 Nota: Se deja constancia que las presentes Transferencias, implican su tramitación ante esta Gerencia del Registro de Jugadores, sin perjuicio de la situación de estos Jugadores en el Tribunal de Disciplina Deportiva, y el Departamento de Medicina Deportiva de esta Asociación. Jugador Procedencia Destino Expediente Transferencias Interclubes Autorizadas ACEVEDO JOEL VALENTIN Atlanta Acassuso 19007108 ACEVEDO JONATHAN LAUTARO All Boys Almirante Brown 19002783 ACEVEDO LUCIO SEBASTIAN Sportivo Italiano Liniers 19003444 ACOSTA AGUSTIN TOMAS Chacarita Juniors Central Ballester 19007170 ACOSTA CRISTALDO CRISTIAN D Atlanta Liniers 19003446 ACOSTA GONZALEZ GABRIEL AL Talleres R.E. Tristán Suárez 19006981 ACOSTA JUAN PABLO Def. de Belgrano Dep. Armenio 19003386 ACOSTA RODRIGO MATIAS Banfield Temperley 19006314 ACUÑA ALEJANDRO EZEQUIEL Muñiz Central Ballester 19007087 ACUÑA JUAN PABLO Brown (Adrogué) Argentino de Quilmes 19007030 ACUÑA LEONARDO JULIAN Juventud Unida Acassuso 19007107 AGUILERA BRIAN NICOLAS Centro Español Sportivo Italiano 19003566 AGUIRRE GASTON DAMIAN Tristán Suárez San Martín (Burzaco) 19007136 AGUIRRE KEVIN IVAN J.J. Urquiza Alem 19003817 AGUIRRE SEBASTIAN LEANDRO San Martín (Burzaco) Claypole 19007171 ALARCON JUAN CRUZ Gral. Lamadrid Acassuso 19007102 ALARCON RODRIGO EZEQUIEL Ituzaingó Argentino de Merlo 19003681 ALBARENGA GONZALEZ FRANCO San Miguel Argentino de Merlo 19007157 ALCARAZ MATIAS San Carlos Colegiales 19007127 ALEGRE LUCAS MIGUEL ANGEL Dep. Merlo Alem 19003821 ALFONSO ENZO GABRIEL Muñiz Central Ballester 19007140 ALVARENGA AGUSTIN Racing Club Temperley 19006312 ALVAREZ RODRIGO NICOLAS Centro Español Ituzaingó 19003187 AMARILLA GUSTAVO HERNAN Chacarita Juniors Acassuso 19007103 AMARILLA MACIEL KEVIN ROY Los Andes Sportivo Italiano 19003574 AMARILLA NICOLAS OSCAR Chacarita Juniors Colegiales 19007130 AMARILLA THIAGO DANIEL San Martín (M. -

Estrategias Compositivas En La Música Electroacústica Rodrigo Sigal

Estrategias compositivas en la música electroacústica Rodrigo Sigal Estrategias compositivas en la música electroacústica Generación de materiales y creación de un lenguaje musical eficaz Traducción Nicolás Varchausky y Teresa Riccardi UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE QUILMES Rector Mario E. Lozano Vicerrector Alejandro Villar Bernal, 2014 Colección: Música y Ciencia Dirigida por Oscar Pablo Di Liscia Índice Sigal, Rodrigo Estrategias compositivas en la música electroacústica. - 1a ed. - Bernal: Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, 2014. 136 p.; 21x15 cm. - (Música y ciencia / Pablo Di Liscia) Nota a la edición en castellano .................................. 11 ISBN 978-987-558-307-8 Agradecimientos .............................................. 13 1. Música Electroacústica. I. Título Introducción ................................................. 15 CDD 786.74 Capítulo I. El material ......................................... 17 El lenguaje y el material en la música electroacústica ................. 17 Título original: Compositional strategies in electroacustic music. Generating materials Lenguaje ................................................. 17 and creating an effective musical lenguage in electroacustic music Diseño del material y del lenguaje ............................. 19 El material sonoro ............................................. 20 Traducción: Nicolás Varchausky y Teresa Riccardi Fuentes sonoras en Cycles .................................... 21 La jerarquía del material sonoro en Friction of things in other places .... 23 Material -

Provincia Ciudad Apellido Nombre Emprendimiento Buenos Aires

Provincia Ciudad Apellido Nombre Emprendimiento Buenos Aires Lanus Almeida Gonzalo Kuttercraft Buenos Aires mar del plata Alvarez Diego Fabricacion de Impresoras 3D Buenos Aires La Plata Butrón Jorge Alejandro EL TRIUNFO Buenos Aires Tigre Conde Francisco MoTu - Modulos Tubulares Buenos Aires Cañuelas Dotzel Hernan RUYI SAS Buenos Aires Tres Arroyos Elgart Leonardo Eco Sniper - Milar Agro Tech S.R.L. Buenos Aires Mar del Plata Erriquenz Florencia Polydoorwind SA Buenos Aires Adrogue Estrada Martin La Teodora Buenos Aires San Isidro figueroa santiago Tu VideoCV Buenos Aires SAN ISIDRO Filgueira Risso Fatima Leaf Social -Silobag Buenos Aires Ituzaingó Gaitan Ivan Leandro Crowfunding BA Buenos Aires Avellaneda Gergela Carlos Alarma para entraderas Buenos Aires la plata Gimenez Leonardo go4clic Buenos Aires La Plata Gramundo Matias Tu Punto free spirit SRL Ahorro de energía eléctrica en la Buenos Aires Bahia Blanca Granieri Fernando Bautistaindustria plástica. Sistema Misura Buenos Aires San Fernando Hansen Fran Calares Energías Renovables Buenos Aires San Francisco SolanoHartman Daniel Econciencia Buenos Aires City Bell Justiniano Ramón Goarts Trust Fund Buenos Aires Morón Lamas Fabio TAR Volferme Buenos Aires OLIVOS MATTA RODRIGO MINIMAHUELLA (talleres sustentables) Buenos Aires capilla del senor Mercado VirasoroJuan locomóviles Buenos Aires Bahía Blanca Nielsen Rodrigo Celleric Buenos Aires san cayetano olea pablo cesar ascensor para piletas Buenos Aires Mar Del Plata Ortiz Alejandro BillApp Buenos Aires Quilmes Padin Sebastian Verdeagua Buenos Aires Lanus Oeste Pose Gerardo GV Soluciones Buenos Aires Olavarria Ribrocchi Lucas RC GROUP Buenos Aires Pilar Rigo Ángeles ZUBI Buenos Aires Florencio Varela RISSO MAURICIO DEMEDIS by UCOSMOS Buenos Aires Mar del Plata Robetto José PONCE Buenos Aires Mar del Plata Russo Gustavo Corvus Buenos Aires Bragado Simonet Carina Nosotras Calzado Artesanal Buenos Aires OLIVOS Villaverde Mayra Villaverde Alimentacion Consciente Catamarca Catamarca Araoz Juan Pablo ReciclAds - Reciclologia S.A.S. -

Political Machines and Networks of Brokers: the Case of the Argentine Peronist Party

Political Machines and Networks of Brokers: The Case of the Argentine Peronist Party By Rodrigo Esteban Zarazaga A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Robert Powell, Co-Chair Professor David Collier, Co-Chair Professor Leonardo Arriola Professor Santiago Oliveros Fall 2011 Abstract Political Machines and Networks of Brokers: The Case of the Argentine Peronist Party by Rodrigo Esteban Zarazaga Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Robert Powell, Co-Chair Professor David Collier, Co-Chair Machine parties have been an important focus in political science during the past decade. The Argentine Partido Justicialista (the Peronist Party, or PJ) is a well-known case of an electorally successful party machine, and scholars have repeatedly noted the salience of brokers (called punteros in Argentina) for the PJ political strategy and its political hegemony. However, key political dynamics that make brokers in efficient political agents and the PJ a successful party machine remained unexplained. This study shows how party machines and their brokers operate by studying the case of the Peronist Party. Peronism has recently achieved a remarkable consolidation of power through control of electoral districts by networks of municipal mayors and brokers. This has been accomplished especially in the Conurbano Bonaerense (CB), i.e., the 33 municipalities surrounding the city of Buenos Aires. Since the 1983 re-democratization up to 2010, the PJ has won 168 out of 212 (a remarkable 80 percent) mayoral elections in the CB. -

California State University, Northridge an Analysis of Astor Piazzolla's

California State University, Northridge An Analysis of Astor Piazzolla’s Histoire du Tango for Flute and Guitar and the Influence of Latin Music on Flute Repertoire A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Performance By Sheila Molazadeh December 2013 The thesis of Sheila Molazadeh is approved: _____________________________________ __________________ Professor Sandra Kipp Date _____________________________________ __________________ Dr. Liviu Marinescu Date _____________________________________ __________________ Dr. Lawrence Stoffel, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Table of Contents Signature Page ii Abstract iv Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: The Life of Astor Piazzolla and Influences on his Music 3 Chapter 3: The History and Evolution of the Tango 8 Chapter 4: An Analysis of Histoire du Tango for Flute and Guitar 13 Chapter 5: The Influence of Latin Music on Flute Repertoire 19 Conclusion 24 Bibliography 25 iii Abstract An Analysis of Astor Piazzolla’s Histoire du Tango for Flute and Guitar and the Influence of Latin Music on Flute Repertoire By Sheila Molazadeh Master of Music in Performance Latin music has made vast contributions to many cultures and societies over time. This multifaceted genre encompasses a wide variety of sounds and styles that have evolved numerous times. The “Latin Craze” has captured many audiences throughout the history of Latin music and dance with its typically lustful and provocative nature, colorful melodies and various dance styles. The tango, in particular, is oftentimes associated with the late Argentinian composer Astor Piazzolla, one the greatest to ever compose that genre of music on such a large scale. -

Program Notes

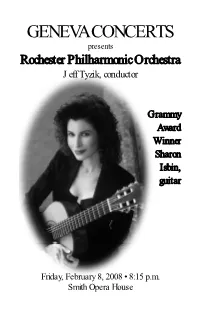

GENEVA CONCERTS presents Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra Jeff Tyzik, conductor Grammy Award Winner Sharon Isbin, guitar Friday, February 8, 2008 • 8:15 p.m. Smith Opera House 1 GENEVA CONCERTS, INC. 2007-2008 SEASON Friday, 21 September 2007, 8:15 p.m. Sherrie Maricle & the DIVA Jazz Orchestra Saturday, 27 October 2007, 8:15 p.m. The Philadelphia Dance Company Philadanco! Friday, 8 February 2008, 8:15 p.m. Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra Jeff Tyzik, conductor Sharon Isbin, guitar Music of Surinach, Piazzolla, Tyzik, Ginestera, Rodrigo, and Santoro Sunday, 2 March 2008, 3:00 p.m. Syracuse Symphony Orchestra James Judd, conductor Tai Murray, violin Music of Berlioz, Mendelssohn, and Elgar Friday, 11 April 2008, 8:15 p.m. Angèle Dubeau & La Pietà Music of Saint-Saëns, Glass, Françaix, LeClerc, Evangelista, Bouchard, Arcuri, Morricone, Piazzolla, Khatchaturian, and Heidrich Performed at the Smith Opera House, 82 Seneca Street, Geneva, NY These concerts are made possible, in part, with public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency, and by a continuing subscription from Hobart and William Smith Colleges. 2 GENEVA CONCERTS, INC. Friday, February 8, 2008 at 8:15 p.m. Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra Christopher Seaman, Music Director Jeff Tyzik, conductor Sharon Isbin, guitar Carlos Surinach Feria mágica (Magical fair) Astor Piazzolla Tangazo arr. Jeff Tyzik Three Pieces for Guitar and Orchestra Antonio Lauro Waltz No. 3, Natalia Leo Brouwer Canción de Cuna (Lullaby) based on Duerme Negrita (Sleep, Little One) by Elisio Grenet Isaias Savio Batucada Sharon Isbin, guitar Alberto Ginastera Four Dances from Estancia, Op. 8a I. -

Boletin Informativo

BOLETIN INFORMATIVO ______________________________________________________________________________________________ Nº 44 LA PLATA, viernes 29 de julio de 2016 ______________________________________________________________________________________________ EL SEÑOR MINISTRO DE SEGURIDAD COMUNICA SUMARIO RESOLUCIONES N° 968, 970, 971, 973, 979, 982, 983, 984, 985, 989, 990, 991, 992, 993, 994, 1036, 1037, 1038, 1039, 1040 Y 1041, RECONOCIENDO EN CALIDAD DE CADETES EN LAS ACADEMIAS DE UNIDAD DE POLICÍA DE PREVENCIÓN LOCAL DE BAHÍA BLANCA, ALMIRANTE BROWN, ESTEBAN ECHEVERRÍA, BERAZATEGUI, JOSÉ C. PAZ, ESCOBAR, DOLORES, ITUZAINGÓ, ENSENADA, MIRAMAR, MORENO, LAS HERAS, CAÑUELAS, SAN ANTONIO DE ARECO, RAMALLO, PILAR, SAN NICOLÁS, MERCEDES, CHACABUCO, GENERAL RODRÍGUEZ Y CASTELLI. RESOLUCIÓN N° 1023, FIJANDO EN EL ÁMBITO DE LA SUPERINTENDENCIA GENERAL DE POLICÍA, SUPERINTENDENCIA DE SEGURIDAD SINIESTRAL, DIRECCIÓN DE EXPLOSIVOS, LA BASE OPERATIVA DE LA DELEGACIÓN DE EXPLOSIVOS MERCEDES. RESOLUCIÓN N° 1024, FIJANDO EN EL ÁMBITO DE LA SUPERINTENDENCIA GENERAL DE POLICÍA, COORDINACIÓN OPERATIVA DE SEGURIDAD, SUPERINTENDENCIA DE SEGURIDAD REGIÓN INTERIOR CENTRO, JEFATURA DE SEGURIDAD GUAMINÍ, LA BASE OPERATIVA DEL GRUPO DE APOYO DEPARTAMENTAL (G.A.D.) GUAMINÍ. RESOLUCIÓN N° 1025, CREANDO EN EL ÁMBITO DE LA SUPERINTENDENCIA GENERAL DE POLICÍA, SUPERINTENDENCIA DE POLÍTICAS DE GÉNERO, LA COMISARÍA DE LA MUJER Y LA FAMILIA MONTE HERMOSO. RESOLUCIÓN N° 1029, DESIGNANDO EN LA SUPERINTENDENCIA GENERAL DE POLICÍA, SUPERINTENDENCIA DE COORDINACIÓN ADMINISTRATIVA, CARGO DE DIRECTOR COORDINACIÓN DE DELEGACIONES ADMINISTRATIVAS DEPARTAMENTALES. RESOLUCIÓN N° 1035, RECONOCIENDO EN CALIDAD DE CADETES, EN LA ESCUELA DE POLICÍA “JUAN VUCETICH” Y SUS SEDES DESCENTRALIZADAS, A CIUDADANOS. RESOLUCIÓN DE LA SUBSECRETARÍA DE PLANIFICACIÓN, GESTIÓN Y EVALUACIÓN N° 034, APROBANDO EL CURSO DE ACTUALIZACIÓN DENOMINADO “LA INVESTIGACIÓN CRIMINALÍSTICA EN LOS DELITOS CONTRA LA INTEGRIDAD SEXUAL”, DESTINADO AL PERSONAL MÉDICO DEPENDIENTE DE LA SUPERINTENDENCIA DE POLICÍA CIENTÍFICA. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2020 12:59:08 PM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jamal Aazizi Chargé de la logistique Association Tazghart Morocco Luz Abayan Program Officer Child Rights Coalition Asia Philippines Babak Abbaszadeh President And Chief Toronto Centre For Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership In Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Education for Employment - United States EFE Ziad Abdel Samad Executive Director Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development TAZI Abdelilah Président Associaion Talassemtane pour Morocco l'environnement et le développement ATED Abla Abdellatif Executive Director and The Egyptian Center for Egypt Director of Research Economic Studies Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Baako Abdul-Fatawu Executive Director Centre for Capacity Ghana Improvement for the Wellbeing of the Vulnerable (CIWED) Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Dr. Abel Executive Director Reach The Youth Uganda Switzerland Mwebembezi (RTY) Suchith Abeyewickre Ethics Education Arigatou International Sri Lanka me Programme Coordinator Diam Abou Diab Fellow Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development Hayk Abrahamyan Community Organizer for International Accountability Armenia South Caucasus and Project Central Asia Aliyu Abubakar Secretary General Kano State Peace and Conflict Nigeria Resolution Association Sunil Acharya Regional Advisor, Climate Practical Action Nepal and Resilience Salim Adam Public Health -

N° APELLIDO NOMBRE DNI N° Mat Categoria Prof. Direcciòn Localidad

Categoria N° APELLIDO NOMBRE DNI N° Mat Prof. Direcciòn Localidad Sede Votacion 1 Abdala Maricel Hilda Aida 27.817.018 96 C-ID Pringles 473 San Nicolás San Nicolas 2 ABOUEID ROSA 5.930.596 396 B1-C1 PASAJE VILLALONGA 1034 Ituzaingo Moron 3 Adura María Belén 35.048.767 105 A1 Angel Roffo 542 Mar del Plata Mar del Plata 4 Aguilar Maria Haydee 17708955 244 C1 Av. Juan Manuel de Rosas 470 , Depto 5 pb. Lomas del Mirador-La Matanza Moron 5 Aldasoro Julio 24.104.465 191 C-ID Barrio Jardin, Casa 146 Tandil Tandil 6 Aliani Gustavo Damian 25925165 346 C-ID Pte Roca 705 San Nicolas San Nicolas 7 Aller Atucha María 31.380.113 619 A1 La Pampa 335 Mar del Plata Mar del Plata 8 Alvarez Facundo 28102142 5 A1 Colon 1076 Piso 3 (Porteria) Mar del Plata Mar del Plata 9 ALVAREZ DIEGO GERMAN 28765172 247 B-ID 13 N 1931 Miramar Mar del Plata 10 ALVAREZ Patricia Laura 11.958.995 130 B1 El Macurú 58 Barrio Alas Ciudad Evita- La Matanza Moron 11 Amor Bernardo 34671127 635 A1 Villanueva 340 Pehuen Co, Coronel Rosales Bahia Blanca 12 Araldi Melina 36.644.478 153 C1 Geranios y Abetos, Bosque P. Ramos Mar del Plata Mar del Plata 13 Arcaria Carlos Martin 36.189.170 582 B1 Calle 1 N879 piso 2 D La Plata La Plata 14 Armendia Claudia Adriana 14.326.146 620 B1-C1 Independencia 395 Lobos Moron 15 ASENSIO MARTA MÓNICA 6.655.043 24 A1 ASTURIAS 1230/52 M04 P01D05 Mar del Plata Mar del Plata 16 AUZQUI MACHADO CARLOS JOSÉ 11.362.708 424 C-ID Av.