Cole Porter: Harmonious Hedonist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music, Dance and Theatre (MDT) 1

Music, Dance and Theatre (MDT) 1 MDT 510 Latin American Music (3 Credits) MUSIC, DANCE AND THEATRE A course in the music of selected Latin America countries offering music and Spanish-language majors and educators perspectives into the (MDT) musical traditions of this multifaceted region. Analysis of the music will be discussed in terms that accommodate non specialists, and all lyrics MDT 500 Louis Armstrong-American Hero (3 Credits) will be supplied with English translations. A study of the development of jazz with Louis Armstrong as the vehicle: MDT 511 Vocal Pedagogy (3 Credits) who he influenced and how he did it. Comparative analytical studies with This course is to provide the student of singing a deeper understanding his peers and other musicians are explored. of the vocal process, physiology, and synergistic nature of the vocal MDT 501 Baroque Music (3 Credits) mechanism. We will explore the anatomical construction of the voice as This course offers a study of 17th and 18th century music with particular well as its function in order to enlighten the performer, pedagogue and emphasis on the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, Dietrich Buxtehude, scholar. Each student will learn to codify a practical knowledge of, and Arcangelo Corelli, Francois Couperin, Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, skill in, teaching voice. George Frederick Handel, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Claudio Monteverdi, Jean- MDT 520 Musical On B'Way&Hollywood I (3 Credits) Philippe Rameau, Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti, Gerog Telemann, This course offers an analysis of current Broadway musicals with special and Antonio Vivaldi. seminars with those connected with one or two productions. -

A Quantitative Analysis of the Songs of Cole Porter and Irving Berlin

i DEVELOPMENT OF CREATIVE EXPERTISE IN MUSIC: A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SONGS OF COLE PORTER AND IRVING BERLIN A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Richard W. Hass January, 2009 ii ABSTRACT Previous studies of musical creativity lacked strong foundations in music theory and music analysis. The goal of the current project was to merge the study of music perception and cognition with the study of expertise-based musical creativity. Three hypotheses about the nature of creativity were tested. According to the productive-thinking hypothesis, creativity represents a complete break from past knowledge. According to the reproductive-thinking hypothesis, creators develop a core collection of kernel ideas early in their careers and continually recombine those ideas in novel ways. According to what can be called the field hypothesis, creativity involves more than just the individual creator; creativity represents an interaction between the individual creator, the domain in which the creator works, and the field, or collection of institutions that evaluate creative products. In order to evaluate each hypothesis, the musical components of a sample of songs by two eminent 20 th century American songwriters, Cole Porter and Irving Berlin, were analyzed. Five separate analyses were constructed to examine changes in the psychologically salient musical components of Berlin’s and Porter’s songs over time. In addition, comparisons between hit songs and non-hit songs were also drawn to investigate whether the composers learned from their cumulative songwriting experiences. Several developmental trends were found in the careers of both composers; however, there were few differences between hit songs and non-hit songs on all measures. -

KEVIN COLE “America's Pianist” Kevin Cole Has Delighted

KEVIN COLE “America’s Pianist” Kevin Cole has delighted audiences with a repertoire that includes the best of American Music. Cole’s performances have prompted accolades from some of the foremost critics in America. "A piano genius...he reveals an understanding of harmony, rhythmic complexity and pure show-biz virtuosity that would have had Vladimir Horowitz smiling with envy," wrote critic Andrew Patner. On Cole’s affinity for Gershwin: “When Cole sits down at the piano, you would swear Gershwin himself was at work… Cole stands as the best Gershwin pianist in America today,” Howard Reich, arts critic for the Chicago Tribune. Engagements for Cole include: sold-out performances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl; BBC Concert Orchestra at Royal Albert Hall; National Symphony at the Kennedy Center; Hong Kong Philharmonic; San Francisco Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra (London); Boston Philharmonic, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (Australia) Minnesota Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Seattle Symphony,Vietnam National Symphony Orchestra; New Zealand Symphony, Edmonton Symphony (Canada), Ravinia Festival, Wolf Trap, Savannah Music Festival, Castleton Festival, Chautauqua Institute and many others. He made his Carnegie Hall debut with the Albany Symphony in May 2013. He has shared the concert stage with, William Warfield, Sylvia McNair, Lorin Maazel, Brian d’Arcy James, Barbara Cook, Robert Klein, Lucie Arnaz, Maria Friedman, Idina Menzel and friend and mentor Marvin Hamlisch. Kevin was featured soloist for the PBS special, Gershwin at One Symphony Place with the Nashville Symphony. He has written, directed, co- produced and performed multimedia concerts for: The Gershwin’s HERE TO STAY -The Gershwin Experience, PLAY IT AGAIN, MARVIN!-A Celebration of the music of Marvin Hamlisch with Pittsburgh Symphony and Chicago Symphony and YOU’RE THE TOP!-Cole Porter’s 125th Birthday Celebration and I LOVE TO RHYME – An Ira Gershwin Tribute for the Ravinia Festival with Chicago Symphony. -

Cole Porter: the Social Significance of Selected Love Lyrics of the 1930S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository Cole Porter: the social significance of selected love lyrics of the 1930s by MARILYN JUNE HOLLOWAY submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject of ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IA RABINOWITZ November 2010 DECLARATION i SUMMARY This dissertation examines selected love lyrics composed during the 1930s by Cole Porter, whose witty and urbane music epitomized the Golden era of American light music. These lyrics present an interesting paradox – a man who longed for his music to be accepted by the American public, yet remained indifferent to the social mores of the time. Porter offered trenchant social commentary aimed at a society restricted by social taboos and cultural conventions. The argument develops systematically through a chronological and contextual study of the influences of people and events on a man and his music. The prosodic intonation and imagistic texture of the lyrics demonstrate an intimate correlation between personality and composition which, in turn, is supported by the biographical content. KEY WORDS: Broadway, Cole Porter, early Hollywood musicals, gays and musicals, innuendo, musical comedy, social taboos, song lyrics, Tin Pan Alley, 1930 film censorship ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to thank Professor Ivan Rabinowitz, my supervisor, who has been both my mentor and an unfailing source of encouragement; Dawie Malan who was so patient in sourcing material from libraries around the world with remarkable fortitude and good humour; Dr Robin Lee who suggested the title of my dissertation; Dr Elspa Hovgaard who provided academic and helpful comment; my husband, Henry Holloway, a musicologist of world renown, who had to share me with another man for three years; and the man himself, Cole Porter, whose lyrics have thrilled, and will continue to thrill, music lovers with their sophistication and wit. -

Critical Perspectives on American Musical Theatre Thea

Critical Perspectives on American Musical Theatre Thea. 80200, Spring 2002 David Savran, CUNY Feb 4—Introduction: One Singular Sensation To be read early in the semester: DiMaggio, “Cultural Boundaries and Structural Change: The Extension of the High Culture Model to Theater, Opera, and the Dance, 1900-1940;” Block, “The Broadway Canon from Show Boat to West Side Story and the European Operatic Ideal;” Savran, “Middlebrow Anxiety” 11—Kern, Hammerstein, Ferber, Show Boat Mast, “The Tin-Pan-Tithesis of Melody: American Song, American Sound,” “When E’er a Cloud Appears in the Blue,” Can’t Help Singin’; Berlant, “Pax Americana: The Case of Show Boat;” 18—No class 20—G. and I. Gershwin, Bolton, McGowan, Girl Crazy; Rodgers, Hart, Babes in Arms ***Andrea Most class visit*** Most, Chapters 1, 2, and 3 of her manuscript, “We Know We Belong to the Land”: Jews and the American Musical Theatre; Rogin, Chapter 1, “Uncle Sammy and My Mammy” and Chapter 2, “Two Declarations of Independence: The Contaminated Origins of American National Culture,” in Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot; Melnick, “Blackface Jews,” from A Right to Sing the Blues: African Americans, Jews, and American Popular Song 25— G. and I. Gershwin, Kaufman, Ryskind, Of Thee I Sing, Shall We Dance Furia, “‘S’Wonderful: Ira Gershwin,” in his Poets of Tin Pan Alley, Mast, “Pounding on Tin: George and Ira Gershwin;” Roost, “Of Thee I Sing” Mar 4—Porter, Anything Goes, Kiss Me, Kate Furia, “The Tinpantithesis of Poetry: Cole Porter;” Mast, “Do Do That Voodoo That You Do So Well: Cole Porter;” Lawson-Peebles, “Brush Up Your Shakespeare: The Case of Kiss Me Kate,” 11—Rodgers, Hart, Abbott, On Your Toes; Duke, Gershwin, Ziegfeld Follies of 1936 Furia, “Funny Valentine: Lorenz Hart;” Mast, “It Feels Like Neuritis But Nevertheless It’s Love: Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart;” Furia, Ira Gershwin: The Art of the Lyricist, pages 125-33 18—Berkeley, Gold Diggers of 1933; Minnelli, The Band Wagon Altman, The American Film Musical, Chaps. -

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) Was An

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) was an American composer and songwriter. Born to a wealthy family in Indiana, he defied the wishes of his dom ineering grandfather and took up music as a profession. Classically trained, he was drawn towards musical theatre. After a slow start, he began to achieve succe ss in the 1920s, and by the 1930s he was one of the major songwriters for the Br oadway musical stage. Unlike many successful Broadway composers, Porter wrote th e lyrics as well as the music for his songs. After a serious horseback riding accident in 1937, Porter was left disabled and in constant pain, but he continued to work. His shows of the early 1940s did not contain the lasting hits of his best work of the 1920s and 30s, but in 1948 he made a triumphant comeback with his most successful musical, Kiss Me, Kate. It w on the first Tony Award for Best Musical. Porter's other musicals include Fifty Million Frenchmen, DuBarry Was a Lady, Any thing Goes, Can-Can and Silk Stockings. His numerous hit songs include "Night an d Day","Begin the Beguine", "I Get a Kick Out of You", "Well, Did You Evah!", "I 've Got You Under My Skin", "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" and "You're the Top". He also composed scores for films from the 1930s to the 1950s, including Born to D ance (1936), which featured the song "You'd Be So Easy to Love", Rosalie (1937), which featured "In the Still of the Night"; High Society (1956), which included "True Love"; and Les Girls (1957). -

Paris, New York, and Post-National Romance

Sex and the Series: Paris, New York, and Post-National Romance Dana Heller / love Paris every moment, Every moment of the year I love Paris, why oh why do I love Paris? Because my love is here. —Cole Porter, / Love Paris This essay will examine and contrast two recent popular situation comedies, NBC's Friends and HBO's Sex and the City, as narratives that participate in the long-standing utilization of Paris as trope, or as an instrumental figure within the perennially deformed and reformed landscape of the American national imaginary. My argument is that Paris re-emerges in post-9/11 popular culture as a complex, multi-accentual figure within the imagined mise-en-scene of the world Americans desire. The reasons for this are to a large degree historical: in literature, cinema, television, popular music, and other forms of U.S. cultural production, from the late nineteenth century through the twentieth century and into the twenty first, Paris has remained that city where one ventures, literally and/or imaginatively, to dismember history, or to perform a disarticulation of the national subject that suggests possibilities for the interrogation of national myths and for 0026-3079/2005/4602-145$2.50/0 American Studies, 46:1 (Summer 2005): 145-169 145 146 Dana Heller the articulation of possible new forms of national unity and allegiance. These forms frequently find expression in the romantic transformation of a national citizen-subject into a citizen-subject of the world, a critique of the imperialist aspirations of the nation-state that antithetically masks those same aspirations under the sign of the disillusioned American cosmopolitan abroad. -

Father Riggs of Yale by Stephen Schmalhofer

Dispatch March 24, 2021 05:11 pm Father Riggs of Yale by Stephen Schmalhofer We open in Venice. On an Italian holiday in 1926, early on in his Broadway career, Richard Rodgers bumped into Noël Coward. Together they strolled the Lido before ducking into a friend’s beach cabana, where Coward introduced Rodgers for the first time to “a slight, delicate-featured man with soft saucer eyes.” Cole Porter grinned up at the visitors and insisted that both men join him for dinner that evening at a little place he was renting. Porter sent one of his gondoliers to pick up Rodgers. At his destination, liveried footmen helped him out of the boat. He gazed in wonder up the grand staircase of Porter’s “little place,” the three-story Ca’ Rezzonico, where Robert Browning died and John Singer Sargent once kept a studio. This was not the only dramatic understatement from Porter that day. In the music room after dinner, their host urged Rodgers and Coward to play some of their songs. Afterwards Porter took his turn. “As soon as he touched the keyboard to play ‘a few of my little things,’ I became aware that here was not merely a talented dilettante, but a genuinely gifted theatre composer and lyricist,” recalled Rodgers in his autobiography, Musical Stages. “Songs like ‘Let’s Do It,’ ‘Let’s Misbehave,’ and ‘Two Babes in the Wood,’ which I heard that night for the first time, fairly cried out to be heard from the stage.” Rodgers wondered aloud what Porter was doing wasting his talent and time in a life of Venetian indolence. -

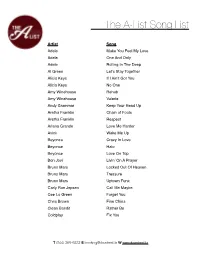

The A-List Songlist 2015

The A-List Song List Artist Song Adele Make You Feel My Love Adele One And Only Adele Rolling In The Deep Al Green Let’s Stay Together Alicia Keys If I Ain’t Got You Alicia Keys No One Amy Winehouse Rehab Amy Winehouse Valerie Andy Grammar Keep Your Head Up Aretha Franklin Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin Respect Ariana Grande Love Me Harder Avicii Wake Me Up Beyonce Crazy In Love Beyonce Halo Beyonce Love On Top Bon Jovi Livin’ On A Prayer Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Cee Lo Green Forget You Chris Brown Fine China Clean Bandit Rather Be Coldplay Fix You T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la The A-List Song List Artist Song Coldplay Viva La Vida Corinne Bailey Rae Put You Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Daft Punk Lose Yourself To Dance David Guetta Ft. Sia Titanium Destiny’s Child Say My Name Earth, Wind, and Fire Let’s Groove Earth, Wind, And Fire September Ed Sheeren Thinking Out Loud Ellie Golding Love Me Like You Do Ellie Golding Need Your Love Emeli Sande Next To Me Estelle American Boy Etta James At Last Frank Sinatra Fly Me To The Moon Frank Valli December ’63 (Oh What A Night) Gnarls Barkley Crazy Guns ‘N’ Roses Sweet Child Of Mine Jackson 5 ABC Jackson 5 I Want You Back Jason Mraz I’m Yours Jay Z & Alicia Keys Empire State Of Mind Jazz Standard Summertime Jessie J Domino John Legend All Of Me T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la The A-List Song List Artist Song John Legend Ordinary People Journey Crazy Little Thing Called Love Journey Don’t Stop Believin Justin Timberlake Señorita Justin Timberlake Sexyback Justin Timberlake Suit & Tie Katy Perry California Girls Katy Perry Firework Katy Perry Roar Katy Perry Teenage Dream Kenny Loggins Footloose Lady Gaga Just Dance Lorde Royals Maroon 5 Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Sugar Maroon 5 Sunday Morning Marvin Gaye What’s Going On Marvin Gaye Ft. -

The A-List Songlist 2017

The A-List Song List Song Artist 24K Magic Bruno Mars A Thousand Years Christina Perri Adorn Miguel Ain't No Mountain High Marvin Gaye Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud to Beg The Temptations Alcoholic Common Kings All My LIfe KC and Jojo All of Me John Legend All Star Smash Mouth Always Be My Baby Mariah Carey American Girl Tom Petty At Last Etta James Baby One More Time Britney Spears Bad Girls Donna Summer Bennie and the Jets Elton John Billie Jean Michael Jackson Blame It On the Boogie Jackson 5 Bless The Broken Road Rascal Flatts Blue Bossa Kenny Dorham Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie A Taste of Honey Boondocks Little Big Town Boot Scootin' Boogie Brooks & Dunn Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la The A-List Song List Song Artist Bye Bye Bye *NSYNC Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Girls Katy Perry California Love 2PAC Can't Feel My Face The Weeknd Can't Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Can't Stop the Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Take My Eyes Off You Lauryn Hill Cantaloupe Island Herbie Hancock Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin Chameleon Herbie Hancock Cheerleader Omi Closer Chainsmokers Come Together The Beatles Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Country Girl (Shake It For Me) Luke Bryan Crazy Gnarles Barkley Crazy In Love Beyonce Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen Crazy Love Brian McKnight Dancing In The Moonlight King Harvest Diamonds Rihanna Do You Love me The Contours Domino Jessie J Don't Know Why Norah Jones T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.la -

Issue 2 2015|2016 SEASON

2015|2016 SEASON Issue 2 TABLE OF Dear Friend, It has finally happened. It always CONTENTS seemed that Kiss Me, Kate was the perfect show for the Shakespeare 1 Title page Theatre Company to produce. It is Recipient of the 2012 Regional Theatre Tony Award® one of the wittiest musical comedies 3 Cast in the canon, featuring the finest Artistic Director Michael Kahn score Cole Porter ever wrote, Executive Director Chris Jennings 4 Director’s Word stuffed to the brim with songs romantic, hilarious, and sometimes both. It is also, not coincidentally, a landmark 8 Story, Musical Numbers adaptation of Shakespeare, a work that no less a critic than and Orchestra W.H. Auden considered greater than Shakespeare’s own The Taming of the Shrew. 9 Music Director’s Word All I can say to the multitudes who have suggested this show to me over the past 29 years is that we waited 13 About the Authors until the moment was right: until we knew we could do a production that could satisfy us, with a cast that could 14 The Taming of work wonders with this material. music and lyrics by Cole Porter the Screwball book by Samuel and Bella Spewack Also, of course, with the right director. He doesn’t need 18 It Takes Two any introduction, having directed two classic (and Performances begin November 17, 2015 classically influenced) musicals for us—2013–2014’s Opening Night November 23, 2015 (Times Two) award-winning staging of A Funny Thing Happened on the Sidney Harman Hall Way to the Forum and 2014–2015’s equally magnificent 24 Mapping the Play Man of La Mancha—but nonetheless I am very happy that STC Associate Artistic Director Alan Paul has agreed to Director Fight Director 26 Kiss Me, Kate and complete his trifecta with Kiss Me, Kate. -

The Life and Solo Vocal Works of Margaret Allison Bonds (1913-1972) Alethea N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 The Life and Solo Vocal Works of Margaret Allison Bonds (1913-1972) Alethea N. Kilgore Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE LIFE AND SOLO VOCAL WORKS OF MARGARET ALLISON BONDS (1913-1972) By ALETHEA N. KILGORE A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Alethea N. Kilgore All Rights Reserved Alethea N. Kilgore defended this treatise on September 20, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Wanda Brister Rachwal Professor Directing Treatise Matthew Shaftel University Representative Timothy Hoekman Committee Member Marcía Porter Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This treatise is dedicated to the music and memory of Margaret Allison Bonds. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to acknowledge the faculty of the Florida State University College of Music, including the committee members who presided over this treatise: Dr. Wanda Brister Rachwal, Dr. Timothy Hoekman, Dr. Marcía Porter, and Dr. Matthew Shaftel. I would also like to thank Dr. Louise Toppin, Director of the Vocal Department of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for assisting me in this research by providing manuscripts of Bonds’s solo vocal works. She graciously invited me to serve as a lecturer and performer at A Symposium of Celebration: Margaret Allison Bonds (1913-1972) and the Women of Chicago on March 2-3, 2013.