Foresight and Hindsight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gheorghe Țițeica - Întemeietor De Şcoală Matematică Românească

1 INSPECTORATUL ŞCOLAR JUDEŢEAN PRAHOVA ŞCOALA GIMNAZIALĂ „RAREŞ VODĂ” PLOIEŞTI Publicaţie periodică a lucrărilor prezentate de elevi la CONCURSUL NAŢIONAL „Matematică – ştiinţă şi limbă universală” Ediţia a IX-a - 2018 2 PLOIEŞTI Nr.42 – SEPTEMBRIE 2018 3 Cuprins 1. Asupra unei probleme date la simulare ................................................................................. 9 Nedelcu Florin Colegiul Tehnic “C. D. Nenițescu” Pitești Prof. coordonator: Veronica Marin 2. Miraculoasa lume a infinitului tainele infinitului ................................................................. 12 Dorica Miruna Școala Gimnazială Corbasca,Județul Bacău Prof. îndrumător Olaru Sorina 3. Metoda reducerii la absurd în rezolvarea problemelor de aritmetică .................................. 14 Buzatu Irina Seminarul Teologic Ortodox "Veniamin Costachi", Mănăstirea Neamț Prof. îndrumător: Asaftei Roxana-Florentina 4. Schimbările climatice la granița dintre știință și ficțiune ..................................................... 16 Ruşanu Maria Ioana, Matei Andreea Mihaela Şcoala Superioară Comercială “Nicolae Kretzulescu”, București Profesori coordonatori Moise Luminita Dominica, dr. Dîrloman Gabriela 5. Gheorghe Țițeica - întemeietor de şcoală matematică românească .................................... 21 Pană Daliana și Mănescu Nadia Liceul Teoretic Mihai Sadoveanu, București Prof. îndrumător Băleanu Mihaela Cristina 6. Aplicații ale coordonatelor carteziene ................................................................................. 26 -

Problems in Trapezoid Geometry Ovidiu T. Pop, Petru I. Braica and Rodica D

Global Journal of Advanced Research on Classical and Modern Geometries ISSN: 2284-5569, Vol.2, Issue 2, pp.55-58 PROBLEMS IN TRAPEZOID GEOMETRY OVIDIU T. POP, PETRU I. BRAICA AND RODICA D. POP ABSTRACT. The purpose of this paper is to present some known and new properties of trapezoids. 2010 Mathematical Subject Classification: 97G40, 51M04. Keywords and phrases: Trapezoid. 1. INTRODUCTION In this section, we recall the well known results: Theorem 1.1. (see [4] or [5]) Let a, b, c, d, be strictly positive real numbers. These numbers can be the lengths of the sides of a quadrilateral if and only if a < b + c + d, b < c + d + a, c < d + a + b, d < a + b + c. (1.1) In general, the strictly positive real numbers a, b, c, d, which verify (1.1) don’t determine in a unique way a quadrilateral. We consider a quadrilateral with rigid sides and con- stant side lengths, its vertices being mobile articulations. Then, this quadrilateral can be deformed in order to obtain another quadrilateral. For trapezoids, the following theorem takes place: Theorem 1.2. (see [5]) Let a, b, c, d, be strictly positive real numbers. Then a, b, c, d can be the lengths of the sides of a trapezoid of bases a and c if and only if a + d < b + c c + d < a + b a + b < c + d or c + b < a + d (1.2) c < a + b + d a < b + c + d By construction, we prove that, in the condition of Theorem 1.2, the trapezoid is uniquely determined. -

MANFRED MOHR B.1938 in Pforzheim, Germany Lives and Works in New York, Since 1981

MANFRED MOHR b.1938 in Pforzheim, Germany Lives and works in New York, since 1981 Manfred Mohr is a leader within the field of software-based art. Co-founder of the "Art et Informatique" seminar in 1968 at Vincennes University in Paris, he discovered Professor Max Bense's writing on information aesthetics in the early 1960s. These texts radically changed Mohr's artistic thinking, and within a few years, his art transformed from abstract expressionism to computer-generated algorithmic geometry. Encouraged by the computer music composer Pierre Barbaud, whom he met in 1967, Mohr programmed his first computer drawings in 1969. His first major museum exhibition, Une esthétique programmée, took place in 1971 at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. It has since become known as the first solo show in a museum of works entirely calculated and drawn by a digital computer. During the exhibition, Mohr demonstrated his process of drawing his computer-generated imagery using a Benson flatbed plotter for the first time in public. Mohr’s pieces have been based on the logical structure of cubes and hypercubes—including the lines, planes, and relationships among them—since 1973. Recently the subject of a retrospective at ZKM, Karlsruhe, Mohr’s work is in the collections of the Centre Pompidou, Paris; Joseph Albers Museum, Bottrop; Ludwig Museum, Cologne; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art; Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen; Kunstmuseum Stuttgart; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Museum Kulturspeicher, Würzburg; Kunsthalle Bremen; Musée d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Strasbourg; Daimler Contemporary, Berlin; Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montreal; McCrory Collection, New York; and Esther Grether Collection, Basel. -

Manfred Mohr 1964- 2011, Réflexions Sur Une Esthétique Programmée

bitforms gallery nyc For Immediate Release 529 West 20th St Contact: Laura Blereau New York NY 10011 [email protected] (212) 366-6939 www.bitforms.com Manfred Mohr 1964- 2011, Réflexions sur une esthétique programmée Sept 9 – Oct 15, 2011 bitforms gallery nyc Opening Reception: Friday, Sept 9, 6:00 – 8:30 PM Gallery Hours: Tue – Sat, 11:00 AM – 6:00 PM It was May 11, 1971 when the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris opened the influential exhibition “Computer Graphics - Une Esthétique Programmée”. A solo exhibition by Manfred Mohr, it featured the first display in a museum of works entirely calculated and drawn by a digital (rather than analog) computer. Revolutionary for its time, these drawings were more than mere curiosities – they signaled a new era of image creation, setting in motion a trajectory of modernism and information aesthetics. Using Manfred Mohr’s work as a touchstone, "1964-2011, Réflexions sur une Esthétique Programmée" reveals, through his art work, a critical period of development in media arts. It examines shifting perspectives in art and the working methods that made the visual conversation of information aesthetics possible. How the computer emerged as a tool for art, results from its capacity for handling systems of high complexity, beyond our normal abilities. Discovering the theoretical writings of the German philosopher Max Bense in the early 1960’s, Mohr was fascinated by the idea of a programmed aesthetic, which coincided with his strong interest in designing electronic sound devices and using scientific imagery in his paintings. Mohr studied in Germany and in Paris at the Ecole de Beaux-Arts, and in 1968 he was a founding member of the seminar 'Art et Informatique' at the University of Vincennes. -

Grigore C. Moisil Omul Și Drumul Său

Grigore C. Moisil Omul și drumul său ste bine cunoscut faptul că în imperiul Austro-ungar, românii din Ardeal nu erau recunoscuți ca o minoritate cu drepturi cetățenești, așa E cum erau maghiarii, sașii și secuii, deși reprezentau 2/3 din populația Transilvaniei. Sentimentul național al românilor era înăbușit prin toate mijloacele. În primul rând nu aveau școli în limba româna și nici drepturi civice. Erau înjosiți și marginalizați, nepermițându-li-se să se manifeste în organele reprezentative decizionale. Cu toate acestea, pentru a se putea apăra de amenințările turcilor, erau imediat înrolați în armată și trimiși pe graniță în punctele cele mai vulnerabile. Așa s-au petrecut lucrurile și în secolul al XVIII-lea, când Maria Tereza a luat hotărârea de a militariza și o serie de sate românești, în anul 1762, din zona județului Bistrița Năsăud de astăzi. Printre acestea s-au numărat și comunele Maieru și Șanț. Evident, anterior s-au făcut o serie de verificări, în privința familiilor si în mod deosebit al membrilor de sex masculin. Datorită acestor demersuri, similar oarecum recensământurilor de astăzi, apare și familia Moisil, având descendenți de frunte, intelectuali și adevărați patrioți, la anul 1758. Această acțiune de militarizare a comunelor românești a permis ridicarea socială, politică și culturală a acestora, oferindu-le ocazia anumitor reprezentanți, patrioți destoinici, să se afirme. Printre aceștia și Grigore Moisil (1814-1891), străbunicul academicianului Grigore C. Moisil. El s-a remarcat în calitate de paroh al ținutului Rodnei, unul din întemeietorii primului liceu românesc din Năsăud. Fratele bunicului său, Grigore, Iuliu Moisil (1859-1947), a fost profesor mai întâi la Slatina si apoi la Târgu Jiu, unde a organizat „Cercuri Culturale” și „bănci populare”. -

On the Meaning of Approximate Reasoning − an Unassuming Subsidiary to Lotfi Zadeh’S Paper Dedicated to the Memory of Grigore Moisil −

Int. J. of Computers, Communications & Control, ISSN 1841-9836, E-ISSN 1841-9844 Vol. VI (2011), No. 3 (September), pp. 577-580 On the meaning of approximate reasoning − An unassuming subsidiary to Lotfi Zadeh’s paper dedicated to the memory of Grigore Moisil − H.-N. L. Teodorescu Horia-Nicolai L. Teodorescu Gheorghe Asachi Technical University, Iasi, Romania Institute for Computer Science, Romanian Academy, Iasi Branch Abstract: The concept of “approximate reasoning” is central to Zadeh’s con- tributions in logic. Standard fuzzy logic as we use today is only one potential interpretation of Zadeh’s concept. I discuss various meanings for the syntagme “approximate reasoning” as intuitively presented in the paper Zadeh dedicated to the memory of Grigore C. Moisil in 1975. Keywords: logic, truth value, natural language, inference. 1 Introduction I perceive three central ideas in Zadeh’s wide conceptual construction in his work until now. The first one is that words and propositions in natural languages, consequently human thoughts are not representable by standard sets and standard binary predicates. The second central idea in many of Zadeh’s papers is that humans perform computations in an approximate manner that real numbers can not represent well. The third idea, which Zadeh presented in his more recent works, is that of granularity of human mental representations and reasoning. These three strong points were represented by Zadeh in various forms and synthesized in the title of his paper on “computing with words” [1]. Most frequently - and Zadeh himself is doing no exception - authors cite as the initial paper clearly stating the approximate reasoning model the one published in the journal Information Sciences, July 1975 [2]. -

1 Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida

Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida Integrated Curriculum Tour Form Education Department, 2015 TITLE: “Salvador Dalí: Elementary School Dalí Museum Collection, Paintings ” SUBJECT AREA: (VISUAL ART, LANGUAGE ARTS, SCIENCE, MATHEMATICS, SOCIAL STUDIES) Visual Art (Next Generation Sunshine State Standards listed at the end of this document) GRADE LEVEL(S): Grades: K-5 DURATION: (NUMBER OF SESSIONS, LENGTH OF SESSION) One session (30 to 45 minutes) Resources: (Books, Links, Films and Information) Books: • The Dalí Museum Collection: Oil Paintings, Objects and Works on Paper. • The Dalí Museum: Museum Guide. • The Dalí Museum: Building + Gardens Guide. • Ades, dawn, Dalí (World of Art), London, Thames and Hudson, 1995. • Dalí’s Optical Illusions, New Heaven and London, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2000. • Dalí, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 2005. • Anderson, Robert, Salvador Dalí, (Artists in Their Time), New York, Franklin Watts, Inc. Scholastic, (Ages 9-12). • Cook, Theodore Andrea, The Curves of Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1979. • D’Agnese, Joseph, Blockhead, the Life of Fibonacci, New York, henry Holt and Company, 2010. • Dalí, Salvador, The Secret life of Salvador Dalí, New York, Dover publications, 1993. 1 • Diary of a Genius, New York, Creation Publishing Group, 1998. • Fifty Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, New York, Dover Publications, 1992. • Dalí, Salvador , and Phillipe Halsman, Dalí’s Moustache, New York, Flammarion, 1994. • Elsohn Ross, Michael, Salvador Dalí and the Surrealists: Their Lives and Ideas, 21 Activities, Chicago review Press, 2003 (Ages 9-12) • Ghyka, Matila, The Geometry of Art and Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1977. • Gibson, Ian, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, New York, W.W. -

Salvador Dalí and Science, Beyond Mere Curiosity

Salvador Dalí and science, beyond mere curiosity Carme Ruiz Centre for Dalinian Studies Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres Pasaje a la Ciencia, no.13 (2010) What do Stephen Hawking, Ramon Llull, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, "Cosmic Glue", Werner Heisenberg, Watson and Crick, Dennis Gabor and Erwin Schrödinger have in common? The answer is simple: Salvador Dalí, a genial artist, who evolved amidst a multitude of facets, a universal Catalan who remained firmly attached to his home region, the Empordà. Salvador Dalí’s relationship with science began during his adolescence, for Dalí began to read scientific articles at a very early age. The artist uses its vocabulary in situations which we might in principle classify as non-scientific. That passion, which lasted throughout his life, was a fruit of the historical times that fell to him to experience — among the most fertile in the history of science, with spectacular technological advances. The painter’s library clearly reflected that passion: it contains a hundred or so books (with notes and comments in the margins) on various scientific aspects: physics, quantum mechanics, the origins of life, evolution and mathematics, as well as the many science journals he subscribed to in order to keep up to date with all the science news. Thanks to this, we can confidently assert that by following the work of Salvador Dalí we traverse an important period in 20th-century science, at least in relation to the scientific advances that particularly affected him. Among the painter’s conceptual preferences his major interests lay in the world of mathematics and optics. -

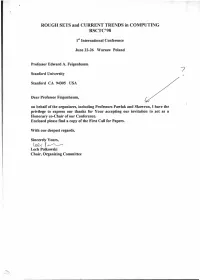

And CURRENT TRENDS in COMPUTING RSCTC'9b

ROUGH SETS and CURRENT TRENDS in COMPUTING RSCTC'9B Ist1st International Conference June 22-26 Warsaw Poland Professor Edward A. Feigenbaum 7 Stanford University Stanford CA 94305 USA Dear Professor Feigenbaum, on behalf of the organizers, including Professors Pawlak and Skowron, I have the privilege to express our thanks for Your accepting our invitation to act as a Honoraryco-Chair of our Conference. Enclosed please find a copy of the First Call for Papers. With our deepest regards, Sincerely Yours, Lech Polkowski Chair, Organizing Committee - * Rough Set Theory, proposed first by Zdzislaw Pawlak in the early 80's, has recently reached a maturity stage. In recent years we have witnessed a rapid growth of interest in rough set theory and its applications, worldwide. Various real life applications ofrough sets have shown their usefulness in many domains. It is felt useful to sum up the present state ofrough set theory and its applications, outline new areas of development and, last but not least, to work out further relationships with such areas as soft computing, knowledge discovery and data mining, intelligent information systems, synthesis and analysis of complex objects and non-conventional models of computation. Motivated by this, we plan to organize the Conference in Poland, where rough set theory was initiated and originally developed. An important aimof the Conference is to bring together eminent experts from diverse fields of expertise in order to facilitate mutual understanding and cooperation and to help in cooperative work aimed at new hybrid paradigms possibly better suited to various aspects of analysis ofreal life phenomena. We are pleased to announce that the following experts have agreedto serve in the Committees of our Conference. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Personal information • Name: Ana-Maria Taloș • E-mail: [email protected] • Nationality: Romanian • Gender: female 1. Educational background • 2012- 2015: PhD degree, thesis “The impact of lifestyle on population health status. Case study: Ialomița county (Romania)”, Faculty of Geography, University of Bucharest • 2010- 2012: Master degree, “Geography of Health Care Resources and Health Tourism” module, Faculty of Geography, University of Bucharest • 2007- 2010: Bachelor degree, Tourism specialization, Faculty of Geography, University of Bucharest • 2003- 2007: ”Grigore Moisil” National College, Social Sciences, Urziceni, Ialomița County, Romania 2. Teaching activity • 2013- present: professor assistant in the Department of Human and Economic Geography, Faculty of Geography, University of Bucharest • 2015-present: organizing and coordinating practical activities for students (Moieciu, Bucharest) • 2015-present: coordinating students’ final paper (health geography, geodemography) 3. Scientific activity Books: • Taloș Ana-Maria, (2017), Stilul de viață și impactul acestuia asupra stării de sănătate a populației. Studiu de caz: județul Ialomița, Editura Universității din București, colecția Geographica, București, ISBN 978-606-16-0877-5 Articles: • Taloș Ana-Maria (2018), Housing conditions and sanitation in Ialomița County: spatial inequalities and relationship with population, Salute, Etica, Migrazione, Dodicesimo Seminario Internazionale di Geografia Medica (Perugia, 14-16.12.2017), Perugia, Guerra Edizioni Edel srl, ISBN: 978-88-557-0627-8 • Taloș Ana-Maria, (2017), Socio-economic deprivation and health outcomes in Ialomita County, Human Geographies - Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography, nr 11 (2), p. 241-253, ISSN–print: 1843–6587 | ISSN–online: 2067–2284 • Taloș Ana-Maria, (2017), Population lifestyle and health in Ialomița County (Romania), Romanian Journal of Geography, Bucuresti, nr 61 (1), p. -

Manfred Mohr: a Formal Language Celebrating 50 Years of Artwork and Algorithms September 7 – November 3, 2019

Manfred Mohr: A Formal Language Celebrating 50 Years of Artwork and Algorithms September 7 – November 3, 2019 Opening Reception: Saturday, September 7, 6 – 8 PM Closing Reception: Sunday, November 3, 4:30 – 6 PM Gallery Hours: Wednesday – Saturday, 11 AM – 6 PM & Sunday 12 – 6 PM bitforms gallery is pleased to celebrate the 50th anniversary (1969 – 2019) of Manfred Mohr writing and creating artwork with algorithms. This exhibition showcases poignant moments throughout the artist’s career, presenting pre-computer artworks from the early 1960s alongside programmed film, wall reliefs, real-time screen-based works, computer-generated works on paper and canvas, and ephemeral objects. Mohr utilizes algorithms to engage rational aesthetics, inviting logic to produce visual outcomes. A Formal Language (named after his 1970 computer drawing) follows the evolution of the artist's programmed systems, including the first computer-generated drawings to the implementation of the hypercube. While Mohr’s career spans over sixty years, this exhibition distinguishes his pioneering use of algorithms decades before it became a tool of contemporary art. In the early 1960s, action painting, atonal music, and geometry were of great interest to Mohr. His early works indicate a confluence of interests in jazz and Abstract Expressionism through weighted strokes and graphic composition. Mohr was connected to instrumentation as a musician himself, playing tenor saxophone and oboe in jazz clubs across Europe. As his practice continued to progress, Max Bense’s theories about rational aesthetics greatly impacted Mohr, ushering in binary, black and white palettes of logical, geometric connections that would soon become his signature. Mohr wrote his first algorithm using the programming language Fortran IV in 1969. -

Manfred Mohr One and Zero 16Th November – 20Th December 2012

Press Release Manfred Mohr one and zero 16th November – 20th December 2012 P198a, plotter drawing, 1977, 60 x 60cm Press Preview: Thursday 15 November, 5 - 6:30pm All my relations to aesthetical decisions always go back to musical thinking, either active in that I played a musical instrument or theoretical in that I see my art as visual music… I was very impressed by Anton Webern's music from the 1920s where for the first time I realized that space, the pause, became as important to the musical construct as the sound itself. So there are these two poles, one and zero. Manfred Mohr one and zero, Manfred Mohr's first solo exhibition in London, presents a concise survey of his fifty-year practice. Harnessing the automatic processes of the computer, Mohr's work brings together his deep interest in music and mathematics to create works that are rigorously minimal but with an elegant lyricism that belie their formal underpinnings. Through drawing, painting, wall- reliefs and screen-based works, the show examines the artist's practice through the prism of music and the idea that what is left out is as important as what remains. Beginning in 1969, Mohr was one of the first visual artists to explore the use of algorithms and computer programs to make independent abstract artworks. His early computer plotter drawings - when he had access to one of the earliest computer driven plotter drawing machines at the Meteorology Institute in Paris - are delicate, spare monochrome works on paper derived from algorithms devised by the artist and executed by the computer.