On the Typology and the Worship Status of Sacred Trees with a Special Reference to the Middle East Amots Dafni*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Present-Day Veneration of Sacred Trees in the Holy Land

ON THE PRESENT-DAY VENERATION OF SACRED TREES IN THE HOLY LAND Amots Dafni Abstract: This article surveys the current pervasiveness of the phenomenon of sacred trees in the Holy Land, with special reference to the official attitudes of local religious leaders and the attitudes of Muslims in comparison with the Druze as well as in monotheism vs. polytheism. Field data regarding the rea- sons for the sanctification of trees and the common beliefs and rituals related to them are described, comparing the form which the phenomenon takes among different ethnic groups. In addition, I discuss the temporal and spatial changes in the magnitude of tree worship in Northern Israel, its syncretic aspects, and its future. Key words: Holy land, sacred tree, tree veneration INTRODUCTION Trees have always been regarded as the first temples of the gods, and sacred groves as their first place of worship and both were held in utmost reverence in the past (Pliny 1945: 12.2.3; Quantz 1898: 471; Porteous 1928: 190). Thus, it is not surprising that individual as well as groups of sacred trees have been a characteristic of almost every culture and religion that has existed in places where trees can grow (Philpot 1897: 4; Quantz 1898: 467; Chandran & Hughes 1997: 414). It is not uncommon to find traces of tree worship in the Middle East, as well. However, as William Robertson-Smith (1889: 187) noted, “there is no reason to think that any of the great Semitic cults developed out of tree worship”. It has already been recognized that trees are not worshipped for them- selves but for what is revealed through them, for what they imply and signify (Eliade 1958: 268; Zahan 1979: 28), and, especially, for various powers attrib- uted to them (Millar et al. -

Download Download

Nisan / The Levantine Review Volume 4 Number 2 (Winter 2015) Identity and Peoples in History Speculating on Ancient Mediterranean Mysteries Mordechai Nisan* We are familiar with a philo-Semitic disposition characterizing a number of communities, including Phoenicians/Lebanese, Kabyles/Berbers, and Ismailis/Druze, raising the question of a historical foundation binding them all together. The ethnic threads began in the Galilee and Mount Lebanon and later conceivably wound themselves back there in the persona of Al-Muwahiddun [Unitarian] Druze. While DNA testing is a fascinating methodology to verify the similarity or identity of a shared gene pool among ostensibly disparate peoples, we will primarily pursue our inquiry using conventional historical materials, without however—at the end—avoiding the clues offered by modern science. Our thesis seeks to substantiate an intuition, a reading of the contours of tales emanating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Levantine area, to Africa and Egypt, and returning to Israel and Lebanon. The story unfolds with ancient biblical tribes of Israel in the north of their country mixing with, or becoming Lebanese Phoenicians, travelling to North Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya in particular— assimilating among Kabyle Berbers, later fusing with Shi’a Ismailis in the Maghreb, who would then migrate to Egypt, and during the Fatimid period evolve as the Druze. The latter would later flee Egypt and return to Lebanon—the place where their (biological) ancestors had once dwelt. The original core group was composed of Hebrews/Jews, toward whom various communities evince affinity and identity today with the Jewish people and the state of Israel. -

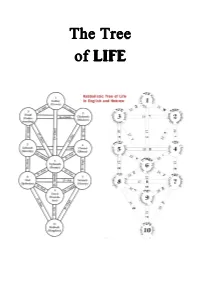

The Tree of LIFE

The Tree of LIFE ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ ~ 4 ~ Trees of Life. From the highest antiquity trees were connected with the gods and mystical forces in nature. Every nation had its sacred tree, with its peculiar characteristics and attributes based on natural, and also occasionally on occult properties, as expounded in the esoteric teachings. Thus the peepul or Âshvattha of India, the abode of Pitris (elementals in fact) of a lower order, became the Bo-tree or ficus religiosa of the Buddhists the world over, since Gautama Buddha reached the highest knowledge and Nirvâna under such a tree. The ash tree, Yggdrasil, is the world-tree of the Norsemen or Scandinavians. The banyan tree is the symbol of spirit and matter, descending to the earth, striking root, and then re-ascending heavenward again. The triple- leaved palâsa is a symbol of the triple essence in the Universe - Spirit, Soul, Matter. The dark cypress was the world-tree of Mexico, and is now with the Christians and Mahomedans the emblem of death, of peace and rest. The fir was held sacred in Egypt, and its cone was carried in religious processions, though now it has almost disappeared from the land of the mummies; so also was the sycamore, the tamarisk, the palm and the vine. The sycamore was the Tree of Life in Egypt, and also in Assyria. It was sacred to Hathor at Heliopolis; and is now sacred in the same place to the Virgin Mary. Its juice was precious by virtue of its occult powers, as the Soma is with Brahmans, and Haoma with the Parsis. -

Changes in Beliefs and Perceptions About the Natural Environment in the Forest-Savanna Transitional Zone of Ghana: the Influence of Religion

NOTA DI LAVORO 08.2010 Changes in Beliefs and Perceptions about the Natural Environment in the Forest-Savanna Transitional Zone of Ghana: The Influence of Religion By Paul Sarfo-Mensah, Bureau of Integrated Rural Development, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources (CANR), Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana William Oduro, Wildlife and Range Management, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources, CANR, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana GLOBAL CHALLENGES Series Editor: Gianmarco I.P. Ottaviano Changes in Beliefs and Perceptions about the Natural Environment in the Forest-Savanna Transitional Zone of Ghana: The Influence of Religion By Paul Sarfo-Mensah, Bureau of Integrated Rural Development, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources (CANR), Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana William Oduro, Wildlife and Range Management, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources, CANR, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana Summary The potential of traditional natural resources management for biodiversity conservation and the improvement of sustainable rural livelihoods is no longer in doubt. In sub-Saharan Africa, extensive habitat destruction, degradation, and severe depletion of wildlife, which have seriously reduced biodiversity and undermined the livelihoods of many people in rural communities, have been attributed mainly to the erosion of traditional strategies for natural resources management. In Ghana, recent studies point to an increasing disregard for traditional rules and regulations, beliefs and practices that are associated with natural resources management. Traditional natural resources management in many typically indigenous communities in Ghana derives from changes in the perceptions and attitudes of local people towards tumi, the traditional belief in super natural power suffused in nature by Onyame, the Supreme Creator Deity. -

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine Biomed Central

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine BioMed Central Research Open Access The supernatural characters and powers of sacred trees in the Holy Land Amots Dafni* Address: Institute of Evolution, the University of Haifa, Haifa 31905, Israel Email: Amots Dafni* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 25 February 2007 Received: 29 November 2006 Accepted: 25 February 2007 Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2007, 3:10 doi:10.1186/1746-4269-3-10 This article is available from: http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/3/1/10 © 2007 Dafni; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract This article surveys the beliefs concerning the supernatural characteristics and powers of sacred trees in Israel; it is based on a field study as well as a survey of the literature and includes 118 interviews with Muslims and Druze. Both the Muslims and Druze in this study attribute supernatural dimensions to sacred trees which are directly related to ancient, deep-rooted pagan traditions. The Muslims attribute similar divine powers to sacred trees as they do to the graves of their saints; the graves and the trees are both considered to be the abode of the soul of a saint which is the source of their miraculous powers. Any violation of a sacred tree would be strictly punished while leaving the opportunity for atonement and forgiveness. The Druze, who believe in the transmigration of souls, have similar traditions concerning sacred trees but with a different religious background. -

The Problem of Mysteriousness of Baba Yaga Character in Religious Mythology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 12 (2013 6) 1857-1866 ~ ~ ~ УДК 7.046 The Problem of Mysteriousness of Baba Yaga Character in Religious Mythology Evgenia V. Ivanova* Ural Federal University named after B.N. Yeltsin 51 Lenina, Ekaterinburg, 620083 Russia Received 28.07.2013, received in revised form 30.09.2013, accepted 05.11.2013 This article reveals the ambiguity of interpretation of Baba Yaga character by the representatives of different schools of mythology. Each of the researchers has his own version of the semantic peculiarities of this culture hero. Who is she? A pagan goddess, a priestess of pagan goddesses, a witch, a snake or a nature-deity? The aim of this research is to reveal the ambiguity of the archetypical features of this character and prove that the character of Baba Yaga as a culture hero of the archaic religious mythology has an influence on the contemporary religious mythology of mass media. Keywords: religious mythology, myth, culture hero, paganism, symbol, fairytale, religion, ritual, pagan priestess. Introduction. “Religious mythology” is examined by the author of the article (Ivanova, a new term, which is relevant to contemporary 2012, p.56). The subject of the research presented religious and cultural studies, philosophy in this article is topography or conceptual space of religion and other sciences focusing on of notional understanding of the fairytale pagan correlation between myth and religion. This culture hero – the character of Baba Yaga. -

P S Y C H O S O C I a L W E L L B E I N G S E R I

PSYCHOSOCIAL WELLBEING SERIES Tree of Life A workshop methodology for children, young people and adults Adapted by Catholic Relief Services with permission from REPSSI Third Edition for a Global Audience 1 REPSSI is a non-profit organisation working to lessen the devastating social and Catholic Relief Services (CRS) was founded in 1943 by the Catholic Bishops of emotional (psychosocial) impact of poverty, conflict, HIV and AIDS among children the United States to serve World War II survivors in Europe. Since then, we have and youth. It is led by Noreen Masiiwa Huni, Chief Executive Officer. REPSSI’s aim is expanded in size to reach 100 million people annually in over 100 countries on five to ensure that all children have access to stable care and protection through quality continents. psychosocial support. We work at the international, regional and national level in East and Southern Africa. Our mission is to assist impoverished and disadvantaged people overseas, working in the spirit of Catholic social teaching to promote the sacredness of human life The best way to support vulnerable children and youth is within a healthy family and and the dignity of the human person. Catholic Relief Services works in partnership community environment. We partner with governments, development partners, with local, national and international organizations and structures in emergency international organisations and NGOs to provide programmes that strengthen response, agriculture and health, as well as microfinance, water and sanitation, communities’ and families’ competencies to better promote the psychosocial peace and justice, capacity strengthening, and education. Although our mission wellbeing of their children and youth. -

Sacred Groves of India : an Annotated Bibliography

SACRED GROVES OF INDIA : AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Kailash C. Malhotra Yogesh Gokhale Ketaki Das [ LOGO OF INSA & DA] INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY AND DEVELOPMENT ALLIANCE Sacred Groves of India: An Annotated Bibliography Cover image: A sacred grove from Kerala. Photo: Dr. N. V. Nair © Development Alliance, New Delhi. M-170, Lower Ground Floor, Greater Kailash II, New Delhi – 110 048. Tel – 091-11-6235377 Fax – 091-11-6282373 Website: www.dev-alliance.com FOREWORD In recent years, the significance of sacred groves, patches of near natural vegetation dedicated to ancestral spirits/deities and preserved on the basis of religious beliefs, has assumed immense anthropological and ecological importance. The authors have done a commendable job in putting together 146 published works on sacred groves of India in the form of an annotated bibliography. This work, it is hoped, will be of use to policy makers, anthropologists, ecologists, Forest Departments and NGOs. This publication has been prepared on behalf of the National Committee for Scientific Committee on Problems of Environment (SCOPE). On behalf of the SCOPE National Committee, and the authors of this work, I express my sincere gratitude to the Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi and Development Alliance, New Delhi for publishing this bibliography on sacred groves. August, 2001 Kailash C. Malhotra, FASc, FNA Chairman, SCOPE National Committee PREFACE In recent years, the significance of sacred groves, patches of near natural vegetation dedicated to ancestral spirits/deities and preserved on the basis of religious beliefs, has assumed immense importance from the point of view of anthropological and ecological considerations. During the last three decades a number of studies have been conducted in different parts of the country and among diverse communities covering various dimensions, in particular cultural and ecological, of the sacred groves. -

The Tree of Life Was Originally Created for Professionals Working with Children Affected by HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa

Tree of Life The Tree of Life was originally created for professionals working with children affected by HIV/AIDS in southern Africa. The process allows children and youth to share their lives through drawing their own tree of life which enables them to speak about their lives in ways that make them stronger without re- traumatizing them. The Tree of Life focuses on strengthening the child and youth’s relationships with their own history, culture, and any significant people and places. The methodology was co-developed through a partnership between Regional Psychosocial Support Initiative (REPSSI) and Dulwich Centre Foundation. To find out more about the Tree of Life and the Dulwich Centre Foundation, visit their website at: hwtt.dup://ww lwichcentre.com.au/tree-of-life.html This activity can be done with children and adults in a short period of time; reserve about an hour to complete the activity. This activity may not be appropriate for small children or those with limited cognition since they are responsible for writing their story on the paper and may not be able to comprehend the purpose of the activity. Once the Tree of Life is complete, give the final copy to the youth. Prior to giving the Tree of Life to the youth make a copy and save it in eWiSACWIS or take a picture and scan the image into eWiSACWIS. Prior to completing the Tree of Life, explain to the child the purpose of the activity: • To share their story from their perspective • To think about where they come from • To think about what they are good at • To think about their -

Attitudinal Values Towards Sacred Groves, Southwest Sichuan, China

IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON Faculty of Natural Sciences Centre of Environmental Policy ATTITUDINAL VALUES TOWARDS SACRED GROVES, SOUTHWEST SICHUAN, CHINA IMPLICATIONS FOR CONSERVATION By Lucy Garrett A report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MSc and/or the DIC. September 2007 1 DECLARATION OF OWN WORK I declare that this thesis Attitudes and Values of Sacred Groves, Southwest Sichuan, China is entirely my own work and that where any material could be construed as the work of others, it is fully cited and referenced, and/or with appropriate acknowledgement given. Signature:..................................................................................................... Name of student: Lucy Garrett Name of supervisor: Dr E.J. Milner-Gulland AUTHORISATION TO HOLD ELECTRONIC COPY OF MSc THESIS Thesis title: Attitudes and Values of Sacred Groves, Southwest Sichuan, China Author: Lucy Garrett I hereby assign to Imperial College London, Centre of Environmental Policy the right to hold an electronic copy of the thesis identified above and any supplemental tables, illustrations, appendices or other information submitted therewith (the .thesis.) in all forms and media, effective when and if the thesis is accepted by the College. This authorisation includes the right to adapt the presentation of the thesis abstract for use in conjunction with computer systems and programs, including reproduction or publication in machine-readable form and incorporation in electronic retrieval systems. Access to the thesis will be limited to ET MSc teaching staff and students and this can be extended to other College staff and students by permission of the ET MSc Course Directors/Examiners Board. Signed: __________________________ Name printed: Lucy Garrett Date: 12 September 2007 ABSTRACT Sacred sites are found throughout the world and are important elements linking both nature and culture and emphasising that humans are intrinsically part of the ecosystem. -

Sources of Mythology: National and International

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & EBERHARD KARLS UNIVERSITY, TÜBINGEN SEVENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY SOURCES OF MYTHOLOGY: NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL MYTHS PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 15-17, 2013 Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany Conference Venue: Alte Aula Münzgasse 30 72070, Tübingen PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, MAY 15 08:45 – 09:20 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:20 – 09:40 OPENING ADDRESSES KLAUS ANTONI Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany JÜRGEN LEONHARDT Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany 09:40 – 10:30 KEYNOTE LECTURE MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA MARCHING EAST, WITH A DETOUR: THE CASES OF JIMMU, VIDEGHA MATHAVA, AND MOSES WEDNESDAY MORNING SESSION CHAIR: BORIS OGUIBÉNINE GENERAL COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY AND METHODOLOGY 10:30 – 11:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Saint Petersburg, Russia UNNOTICED EURASIAN BORROWINGS IN PERUVIAN FOLKLORE 11:00 – 11:30 EMILY LYLE University of Edinburgh, UK THE CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN INDO-EUROPEAN AND CHINESE COSMOLOGIES WHEN THE INDO-EUROPEAN SCHEME (UNLIKE THE CHINESE ONE) IS SEEN AS PRIVILEGING DARKNESS OVER LIGHT 11:30 – 12:00 Coffee Break 12:00 – 12:30 PÁDRAIG MAC CARRON RALPH KENNA Coventry University, UK SOCIAL-NETWORK ANALYSIS OF MYTHOLOGICAL NARRATIVES 2 NATIONAL MYTHS: NEAR EAST 12:30 – 13:00 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia FOUR STORIES OF THE FLOOD IN SUMERIAN LITERARY TRADITION 13:00 – 14:30 Lunch Break WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON SESSION CHAIR: YURI BEREZKIN NATIONAL MYTHS: HUNGARY AND ROMANIA 14:30 – 15:00 ANA R. CHELARIU New Jersey, USA METAPHORS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF MYTHICAL LANGUAGE - WITH EXAMPLES FROM ROMANIAN MYTHOLOGY 15:00 – 15:30 SAROLTA TATÁR Peter Pazmany Catholic University of Hungary A PECHENEG LEGEND FROM HUNGARY 15:30 – 16:00 MARIA MAGDOLNA TATÁR Oslo, Norway THE MAGIC COACHMAN IN HUNGARIAN TRADITION 16:00 – 16:30 Coffee Break NATIONAL MYTHS: AUSTRONESIA 16:30 – 17:00 MARIA V. -

Religious Fundamentalism in Eight Muslim‐

JOURNAL for the SCIENTIFIC STUDY of RELIGION Religious Fundamentalism in Eight Muslim-Majority Countries: Reconceptualization and Assessment MANSOOR MOADDEL STUART A. KARABENICK Department of Sociology Combined Program in Education and Psychology University of Maryland University of Michigan To capture the common features of diverse fundamentalist movements, overcome etymological variability, and assess predictors, religious fundamentalism is conceptualized as a set of beliefs about and attitudes toward religion, expressed in a disciplinarian deity, literalism, exclusivity, and intolerance. Evidence from representative samples of over 23,000 adults in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and Turkey supports the conclusion that fundamentalism is stronger in countries where religious liberty is lower, religion less fractionalized, state structure less fragmented, regulation of religion greater, and the national context less globalized. Among individuals within countries, fundamentalism is linked to religiosity, confidence in religious institutions, belief in religious modernity, belief in conspiracies, xenophobia, fatalism, weaker liberal values, trust in family and friends, reliance on less diverse information sources, lower socioeconomic status, and membership in an ethnic majority or dominant religion/sect. We discuss implications of these findings for understanding fundamentalism and the need for further research. Keywords: fundamentalism, Islam, Christianity, Sunni, Shia, Muslim-majority countries. INTRODUCTION