Mystery in the Music of Anton Bruckner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Lewis in Recital a Feast of Piano Masterpieces

PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL A FEAST OF PIANO MASTERPIECES SAT 14 SEP 2019 QUEENSLAND SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA STUDIO PROGRAM | PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL I WELCOME Welcome to this evening’s recital. I have been honoured to join Queensland Symphony Orchestra this year as their Artist-in- Residence, and am delighted to perform for you tonight. This intimate studio is a perfect setting for a recital, and I very much hope you will enjoy it. The first work on the program is Haydn’s Piano Sonata in E minor. Haydn is well known for his string quartets but he also wrote a great number of piano sonatas, and this one is a particular gem. It showcases the composer’s skill of creating interesting variations of simple musical material. The Three Intermezzi Op.117 are some of Brahms’s saddest and most heartfelt piano pieces. The first Intermezzo was influenced by a Scottish lullaby,Lady Anne Bothwell’s Lament, and was described by Brahms as a ‘lullaby to my sorrows’. This is Brahms in his most introspective mood, with quietly anguished harmonies and dynamic markings that rarely rise above mezzo piano. Finally, tonight’s recital concludes with one of the great peaks of the piano repertoire. The 33 Variations in C on a Waltz by Diabelli is one of Beethoven’s most extreme and all- encompassing works – an unforgettable journey for the listener as much as the performer. Thank you for your attendance this evening and I hope you enjoy the performance. Paul Lewis 2019 Artist-in-Residence IN THIS CONCERT PROGRAM Piano Paul Lewis Haydn Piano Sonata in E minor, Hob XVI:34 Brahms Three Intermezzi, Op.117 INTERVAL Approx. -

The Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra

HansSchmidt-lsserstedt and the StockholmPhilharmonic Orchestra (1957) TheStockholm Philharmonic Orchestra - ALL RECORDINGSMARKED WITH ARE STEREO BIS-CD-421A AAD Totalplayingtime: 71'05 van BEETHOVEN,Ludwig (1770-1827) 23'33 tr SymphonyNo.9 in D minor,Op.125 ("Choral'/, Fourth Movemenl Gutenbuts) 2'.43 l Bars1-91. Conductor.Paavo Berglund Liveconcert at the StockholmConcert Hall 25thMarch 19BB Fadiorecording on tape:Radio Stockholm 1',44 2. Bars92' 163. Conductor:Antal Dor6t Liveconcerl at the StockholmConcert Hall 15thSeptember 1976 Privaterecording on tape.SFO B 276lll 1',56 3 Bars164 '236. Soloist:Sigurd Bjorling, bass Conduclor.Antal Dordti '16th Liveconcert at theStockholm Concert Hall December 1967 Privaterecording on tape.SFO 362 Recordingengineer. Borje Cronstrand 2',27 4 Bars237 '33O' Soloists.Aase Nordmo'Lovberg, soprano, Harriet Selin' mezzo-soprano BagnarUlfung, tenor, Sigurd Biorling' bass Muiit<alisxaSallskapet (chorus master: Johannes Norrby) Conductor.Hans Schmidt-lsserstedt Liveconcert at the StockholmConcert Hall, 19th May 1960 Privaterecording on tape SFO87 Recordingengineer' Borje Cronstrand Bars331 -431 1IAA Soloist:Gosta Bdckelin. tenor MusikaliskaSdllskapet (chorus-master: Johannes Norrbv) Conductor:Paul Kletzki Liveconcert at the StockholmConcerl Hall, ist Octoberi95B Radiorecording on tape:RR Ma 58/849 -597 Bars431 2'24 MusikaliskaSallskapet (chorus-master: Johannes Norroy,l Conductor:Ferenc Fricsay Llverecording at the StockholmConcert Hall,271h February 1957 Radiorecording on tape:RR Ma 571199 Bars595-646 3',05 -

Multivalent Form in Gustav Mahlerʼs Lied Von Der Erde from the Perspective of Its Performance History

Multivalent Form in Gustav Mahlerʼs Lied von der Erde from the Perspective of Its Performance History Christian Utz All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Received: 09/10/2017 Accepted: 19/11/2017 Published: 27/02/2018 Last updated: 27/02/2018 How to cite: Christian Utz, “Multivalent Form in Gustav Mahlerʼs Lied von der Erde from the Perspective of Its Performance History,” Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies (February 27, 2018) Tags: 20th century; Analysis; Bernstein, Leonard; Das Lied von der Erde; Klemperer, Otto; Mahler, Gustav; Performance; Performance history; Rotational form; Sonata form; Strophic form; Walter, Bruno This essay is an expanded version of a paper presented at the symposiumGustav Mahler im Dialog, held at the Gustav Mahler Musikwochen in Toblach/Dobbiaco on July 18, 2017. The research was developed as part of the research project Performing, Experiencing and Theorizing Augmented Listening [PETAL]. Interpretation and Analysis of Macroform in Cyclic Musical Works (Austrian Science Fund (FWF): P 30058-G26; 2017–2020). I am grateful for advice received from Federico Celestini, Peter Revers, Thomas Glaser, and Laurence Willis. Files for download: Tables and Diagrams, Video examples 1-2, Video examples 3-4, Video examples 5-8, Video examples 9-10 Best Paper Award 2017 Abstract The challenge of reconstructing Gustav Mahlerʼs aesthetics and style of performance, which incorporated expressive and structuralist principles, as well as problematic implications of a post- Mahlerian structuralist performance style (most prominently developed by the Schoenberg School) are taken in this article as the background for a discussion of the performance history of Mahlerʼs Lied von der Erde with the aim of probing the model of “performance as analysis in real time” (Robert Hill). -

Monday, June 30Th at 7:30 P.M. Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp Free Admission

JUNE 2008 Listener BLUE LAKE PUBLIC RADIO PROGRAM GUIDE Monday, June 30th at 7:30 p.m. TheBlue Grand Lake Rapids Fine ArtsSymphony’s Camp DavidFree LockingtonAdmission WBLV-FM 90.3 - MUSKEGON & THE LAKESHORE WBLU-FM 88.9 - GRAND RAPIDS A Service of Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp 231-894-5656 http://www.bluelake.org J U N E 2 0 0 8 H i g h l i g h t s “Listener” Volume XXVI, No.6 “Listener” is published monthly by Blue Lake Public Radio, Route Two, Twin Lake, MI 49457. (231)894-5656. Summer at Blue Lake WBLV, FM-90.3, and WBLU, FM-88.9, are owned and Summer is here and with it a terrific live from operated by Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp Blue Lake and broadcast from the Rosenberg- season of performances at Blue Lake Fine Clark Broadcast Center on Blue Lake’s Arts Camp. Highlighting this summer’s Muskegon County Campus. WBLV and WBLU are public, non-commercial concerts is a presentation of Beethoven’s stations. Symphony No. 9, the Choral Symphony, Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp with the Blue Lake Festival Orchestra, admits students of any race, color, Festival Choir, Domkantorei St. Martin from national or ethnic origin and does not discriminate in the administration of its Mainz, Germany, and soloists, conducted programs. by Professor Mathias Breitschaft. The U.S. BLUE LAKE FINE ARTS CAMP Army Field Band and Soldier’s Chorus BOARD OF TRUSTEES will present a free concert on June 30th, and Jefferson Baum, Grand Haven A series of five live jazz performances John Cooper, E. -

PROKOFIEV Hannu Lintu Piano Concertos Nos

Olli Mustonen Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra PROKOFIEV Hannu Lintu Piano Concertos Nos. 2 & 5 SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891–1953) Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16 33:55 1 I Andantino 11:57 2 II Scherzo. Vivace 2:59 3 III Intermezzo. Allegro moderato 7:04 4 IV Finale. Allegro tempestoso 11:55 Piano Concerto No. 5 in G major, Op. 55 23:43 5 I Allegro con brio 5:15 6 II Moderato ben accentuato 4:02 7 III Toccata. Allegro con fuoco 1:58 8 IV Larghetto 6:27 9 V Vivo 6:01 OLLI MUSTONEN, piano Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra HANNU LINTU, conductor 3 Prokofiev Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 5 Honestly frank, or just plain rude? Prokofiev was renowned for his uncompromisingly direct behaviour. On one occasion he berated a famous singer saying – within the hearing of her many admirers – that she understood nothing of his music. Seeing her eyes brim, he mercilessly sharpened his tongue and humiliated her still further: ‘All of you women take refuge in tears instead of listening to what one has to say and learning how to correct your faults.’ One of Prokofiev’s long-suffering friends in France, fellow Russian émigré Nicolas Nabokov, sought to explain the composer’s boorishness by saying ‘Prokofiev, by nature, cannot tell a lie. He cannot even say the most conventional lie, such as “This is a charming piece”, when he believes the piece has no charm. […] On the contrary he would say exactly what he thought of it and discuss at great length its faults and its qualities and give valuable suggestions as to how to improve the piece.’ Nabokov said that for anyone with the resilience to withstand Prokofiev’s gruff manner and biting sarcasm he was an invaluable friend. -

Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin Rundfunkchor Berlin Marek Janowski SYMPHONIA DOMESTICA & DIE TAGESZEITEN Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss SYMPHONIA DOMESTICA & DIE TAGESZEITEN Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin Rundfunkchor Berlin Marek Janowski Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Symphonia statement (if meant sincerely) does not the Frenchman recommended the reference to the (outdated) traditional necessarily win you friends... work be performed only without the genre, in order to subsequently Symphonia Domestica, Op. 53 Domestica, Op. 53 accompanying programme, as it would demolish the internal musical structure 1 Bewegt 5. 03 In fact, the content of the Symphonia certainly distract the listener and and compositional content with 2 Scherzo 12. 46 Richard Strauss was a master at domestica does seem rather trivial, as misrepresent the character of the work. powerful irony. After all, one would 3 Adagio 11. 22 creating double entendres in his the composer places his own, deeply To which Strauss responded: “For me, surely elect a completely diff erent 4 Mäßig langsam. Bewegter 15. 43 music. Nothing is as it seems at fi rst bourgeois family idyll in the spotlight of the poetic programme is no more than genre to accompany the private glance. One should always keep this the musical scene. His original working a means of expressing and developing area of a domestic idyll: an art song, Die Tageszeiten, Op. 76 in mind when dealing with such a title for the work was: “My home. A my perception in a purely musical perhaps, a sonata – but certainly not (Poems by Joseph von Eichendorff ) controversial work as his Symphonia symphonic portrait of myself and my manner; not, as you think, merely a a symphony written for the concert For Male Chorus and Orchestra domestica, Op. -

Super Drama Sunday Marathon

WXXI-TV/HD | WORLD | CREATE | AM1370 | CLASSICAL 91.5 | WRUR 88.5 PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTERLISTINGSFEBRUARY 2012 Super Drama Sunday Marathon Some may relish in watching the Super Bowl on February 5th, while others may long for something a bit more sophisticated. That’s why WXXI is proud to bring back Super Drama Sunday – with two Masterpiece Classic presentations. We’ll kick off the afternoon at 12:30 withReturn to Cranford, where change is racing towards the small, close- knit village of Cranford like a steam train — quite literally. As the railroad continues to encroach on the town, Cranford strives to open to new realities, from surprising romances to unexpected losses and even waltzing! At 3:30 p.m. WXXI-TV/HD makes a touch down with the Emmy Award-winning Downton Abbey. You’ll enjoy the first five episodes of season two back to back, which rejoins the story of the noble Crawley family and their servants at Downton Abbey during the tumultuous World War I era. Return to Cranford airs 12:30 p.m., Downton Abbey at Photo credit: 20 Toe Photo 3:30 p.m., Sunday, February 5 on WXXI-TV/HD Executive Staff FEBRUARY 2012 Volume 3, Issue 4 Norm Silverstein, President & CEO Member & Audience Services ... 585.258.0200 WXXI Main Number ................... 585.325.7500 Susan Rogers, Executive Vice President & General WXXI is a public non-commercial broadcasting station owned and op- Manager Service Interruptions ................. 585.258.0331 Audience Response Line ........... 585.258.0360 erated by WXXI Public Broadcasting Council, a not-for-profit corporation Jeanne E. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season April 23, 2017 MANFRED MARIA HONECK, CONDUCTOR TILL FELLNER, PIANO FRANZ SCHUBERT Selections from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 I. Overture II. Ballet Music No. 2 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto No. 3 for Piano and Orchestra in C minor, Opus 37 I. Allegro con brio II. Largo III. Rondo: Allegro Mr. Fellner Intermission WOLFGANG AMADEUS Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, “Jupiter” MOZART I. Allegro vivace II. Andante cantabile III. Allegretto IV. Molto allegro PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA FRANZ SCHUBERT Overture and Ballet Music No. 2 from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 (1820 and 1823) Franz Schubert was born in Vienna on January 31, 1797, and died there on November 19, 1828. He composed the music for Rosamunde during the years 1820 and 1823. The ballet was premiered in Vienna on December 20, 1823 at the Theater-an-der-Wein, with the composer conducting. The Incidental Music to Rosamunde was first performed by the Pittsburgh Symphony on November 9, 1906, conducted by Emil Paur at Carnegie Music Hall. Most recently, Lorin Maazel conducted the Overture to Rosamunde on March 14, 1986. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings. Performance tine: approximately 17 minutes Schubert wrote more for the stage than is commonly realized. His output contains over a dozen works for the theater, including eight complete operas and operettas. Every one flopped. Still, he doggedly followed each new theatrical opportunity that came his way. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1991, Tanglewood

/JQL-EWOOD . , . ., An Enduring Tradition ofExcellence In science as in the lively arts, fine performance is crafted with aptitude attitude and application Qualities that remain timeless . As a worldwide technology leader, GE Plastics remains committed to better the best in engineering polymers silicones, superabrasives and circuit board substrates It's a quality commitment our people share Everyone. Every day. Everywhere, GE Plastics .-: : ;: ; \V:. :\-/V.' .;p:i-f bhubuhh Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Grant Llewellyn and Robert Spano, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Tenth Season, 1990-91 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman Emeritus J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President T Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, V ice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Mrs. R. Douglas Hall III Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Francis W. Hatch Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Julian T. Houston Richard A. Smith Julian Cohen Mrs. BelaT. Kalman Ray Stata William M. Crozier, Jr. Mrs. George I. Kaplan William F. Thompson Mrs. Michael H. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Nicholas T. Zervas Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett R. Willis Leith, Jr. Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. George R. Rowland Philip K. Allen Mrs. John L. Grandin Mrs. George Lee Sargent Allen G. Barry E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Mrs. John M. Bradley Thomas D. Perry, Jr. -

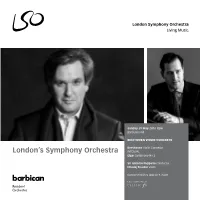

Nikolaj Znaider in 2016/17

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 29 May 2016 7pm Barbican Hall BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTO Beethoven Violin Concerto London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Elgar Symphony No 2 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Nikolaj Znaider violin Concert finishes approx 9.20pm 2 Welcome 29 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to this evening’s LSO ELGAR UP CLOSE ON BBC iPLAYER concert at the Barbican. Tonight’s performance is the last in a number of programmes this season, During April and May, a series of four BBC Radio 3 both at the Barbican and LSO St Luke’s, which have Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s was dedicated explored the music of Elgar, not only one of to Elgar’s moving chamber music for strings, with Britain’s greatest composers, but also a former performances by violinist Jennifer Pike, the LSO Principal Conductor of the Orchestra. String Ensemble directed by Roman Simovic, and the Elias String Quartet. All four concerts are now We are delighted to be joined once more by available to listen back to on BBC iPlayer Radio. Sir Antonio Pappano and Nikolaj Znaider, who toured with the LSO earlier this week to Eastern Europe. bbc.co.uk/radio3 Following his appearance as conductor back in lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts November, it is a great pleasure to be joined by Nikolaj Znaider as soloist, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto. We also greatly look forward to 2016/17 SEASON ON SALE NOW Sir Antonio Pappano’s reading of Elgar’s Second Symphony, following his memorable performance Next season Gianandrea Noseda gives his first concerts of Symphony No 1 with the LSO in 2012. -

Music This Table Outlines What Can Be Found Within Musical Archival Collections in Edinburgh Which Are Relevant to Either Jewish

Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers as well as linking to a variety of additional subject matters. Repository Date Title Relevance Scope Reference National Library of 1781 Scottish Tragic Ballads Jewish literary Printed collection of Glen collection Scotland representation within musical ballad lyrics Shelfmark: Glen 140 a ballad in the collection entitled ‘the Jew’ National Library of 1806 Oliver’s collection of Ballad entitled ‘The Printed collection of Glen.5(1-4) Scotland comic songs’ Jew Peddler’ musical ballad lyrics Edinburgh University 1890-1900 Correspondence between Musician: Professional GB 237 Coll-411/1/L85 Archives Joseph Joachim and Sir Joseph Joachim correspondence; music Donald F. Tovey, Francis composition discussion; John Henry Jenkins, Sir concert dates; social Hubert Parry and Sophie niceties Weisse Edinburgh University 1892 and 1940 Letters between Sophie Musicians: One letter which GB 237 Coll 411/1/L2041 Archives Weisse, Sir Donald Tovey Fanny Behrens mentions Fanny Behrens and Fanny Behrens (wife Gustav Behrens between Tovey and of Gustav Behrens) Sophie Weisse; Second Letter from Behrens to Weisse alerting Miss. Weisse to an article about Tovey's 'absolute ear', news of Behrens recovery and of her sons Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers -

Full Orchestra

John Adams City Noir 2009 34 min for orchestra picc.3(III=picc).3.corA.3(III=bcl).bcl.asax.dbn--6.4.3.1--timp.perc(5):vib/lg sus.cym/SD/bongos; tuned gongs/sus.cym/glsp/mar/tam-t/BD/chimes/vib/low tom-toms/tgl/castanets/cowbell/clave/temple bl; chimes/glsp/tamb/med tam-t/2 timbales/sus.cym/crotales/xyl; BD/tuned gongs/med tam-t/2 sus.cym/mar/crotales/castanet/tgl/glsp; 2 tam-t/BD/sus.cym/tgl/temple block/SD/2 tom-t/timbale/bongo/conga/tuned gongs.trap set--pft--cel--2harps--strings 9790051097791 Orchestra (full score) John Adams photo © Christine Alicino World Premiere: 08 Oct 2009 Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, CA, United States Los Angeles Philharmonic FULL ORCHESTRA Conductor: Gustavo Dudamel Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Absolute Jest 2011 25 min Doctor Atomic Symphony 25 min for string quartet and orchestra 2007 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.2.2.0-timp.perc(2):cowbell/xyl/BD/chimes/glsp/vib-harp-pft.c for orchestra el-strings 2.picc.3(III=corA).3(II=Ebcl, III=bcl).3(III=dbn) -4.4(IV=picc.tpt).3.1-harp-cel-timp-perc(4):crotales/chimes/SD/thunder sheet/glsp/BD/2 This work requires additional technological components and/or amplification. tam-t/2 susp.cym/tuned gongs-strings 9790051097326 (Full score) <u>NOTE</u>: Due to certain balance issues in the orchestration, it is strongly recommended that very light amplification of the solo quartet be used with the sound controlled through a mixing board located at the rear, behind the audience.