Nakivale Settlement Profile Isingiro District, Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jhpiego in Uganda

Uganda Country Profile Jhpiego in Uganda Background Quick Facts Jhpiego has worked in Uganda for more than 30 years, beginning in the early Estimated total population:1 1980s with a project funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development 40.1 million (USAID) to train faculty from Makerere University’s Department of Maternal mortality ratio:2 Obstetrics/Gynecology in reproductive health. In the late 1990s, Jhpiego focused 360/100,000 live births on increasing the capacity of the Ugandan nursing, midwifery, clinical officer and medical schools under the USAID-funded Delivery of Improved Services for Infant mortality rate:1 Health Project. Jhpiego also helped establish the Regional Center for Quality of 54/1,000 live births Health Care in Uganda and seconded a Reproductive Health Advisor to the Center for nearly five years. From 2004 to 2007, Jhpiego worked in Uganda Under-five mortality rate:2 through the University Technical Assistance Project award from the U.S. Centers 66/1,000 live births for Disease Control and Prevention, helping to establish and develop a local nongovernmental organization (NGO) called Protecting Families Against AIDS, 1 Total fertility rate: or PREFA, to scale up services for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission 5.9 of HIV. In 2006, the USAID-funded ACCESS Program, through Jhpiego and Contraceptive prevalence:1 IMA World Health, collaborated on a pilot program in the Kasese District with 26% (modern methods) three faith-based organizations to increase uptake of intermittent preventive 27% (all methods) treatment to prevent malaria in pregnancy (MIP). Jhpiego also provided technical support as a subawardee to Management Sciences for Health (MSH) on a five- HIV prevalence:2 year Reproductive Health, Family Planning and Child Survival (STRIDES for 7.4% Family Health) Project, and expanded access to high-quality HIV prevention, care and treatment services for the Ugandan Military under a subaward with RTI Births with skilled provider:2 International. -

UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details)

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details) SUDAN NARENGEPAK KARENGA KATHILE KIDEPO NP !( NGACINO !( LOPULINGI KATHILE AGORO AGU FR PABAR AGORO !( !( KAMION !( Apoka TULIA PAMUJO !( KAWALAKOL RANGELAND ! KEI FR DIBOLYEC !( KERWA !( RUDI LOKWAKARAMOE !( POTIKA !( !( PAWACH METU LELAPWOT LAWIYE West PAWOR KALAPATA MIDIGO NYAPEA FR LOKORI KAABONG Moyo KAPALATA LODIKO ELENDEREA PAJAKIRI (! KAPEDO Dodoth !( PAMERI LAMWO FR LOTIM MOYO TC LICWAR KAPEDO (! WANDI EBWEA VUURA !( CHAKULYA KEI ! !( !( !( !( PARACELE !( KAMACHARIKOL INGILE Moyo AYUU POBURA NARIAMAOI !( !( LOKUNG Madi RANGELAND LEFORI ALALI OKUTI LOYORO AYIPE ORAA PAWAJA Opei MADI NAPORE MORUKORI GWERE MOYO PAMOYI PARAPONO ! MOROTO Nimule OPEI PALAJA !( ALURU ! !( LOKERUI PAMODO MIGO PAKALABULE KULUBA YUMBE PANGIRA LOKOLIA !( !( PANYANGA ELEGU PADWAT PALUGA !( !( KARENGA !( KOCHI LAMA KAL LOKIAL KAABONG TEUSO Laropi !( !( LIMIDIA POBEL LOPEDO DUFILE !( !( PALOGA LOMERIS/KABONG KOBOKO MASALOA LAROPI ! OLEBE MOCHA KATUM LOSONGOLO AWOBA !( !( !( DUFILE !( ORABA LIRI PALABEK KITENY SANGAR MONODU LUDARA OMBACHI LAROPI ELEGU OKOL !( (! !( !( !( KAL AKURUMOU KOMURIA MOYO LAROPI OMI Lamwo !( KULUBA Koboko PODO LIRI KAL PALORINYA DUFILE (! PADIBE Kaabong LOBONGIA !( LUDARA !( !( PANYANGA !( !( NYOKE ABAKADYAK BUNGU !( OROM KAABONG! TC !( GIMERE LAROPI PADWAT EAST !( KERILA BIAFRA !( LONGIRA PENA MINIKI Aringa!( ROMOGI PALORINYA JIHWA !( LAMWO KULUYE KATATWO !( PIRE BAMURE ORINJI (! BARINGA PALABEK WANGTIT OKOL KINGABA !( LEGU MINIKI -

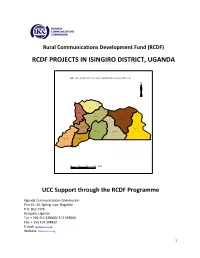

Rcdf Projects in Isingiro District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN ISINGIRO DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F ISING IR O D ISTR IC T SH O W IN G SU B C O U N TIES N M asha Bire re Kab in go R uga ag a Nya kitund a End in zi N gar am a Kas h um b a Kab uy a nd a Kikag ate 10 0 10 20 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....…….3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..….…4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….…………...4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Isingiro district………….…………...5 2- Map of Uganda showing Isingiro district………..………………….………...……..….14 10- Map of Isingiro district showing sub counties………..………………………..…….15 11- Table showing the population of Isingiro district by sub counties…………..15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Isingiro district…………………………………….…….……..16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Astrid L. Mathiassen, John B. Musoke, Peter Opio and Per Schøning Documentsenergy and Poverty a Feasibility Study on Statistics on Access and Use of Energy in Uganda

2005/11 November 2005 Documents Statistics Norway Division for Development Cooperation and Uganda Bureau of Statistics Astrid L. Mathiassen, John B. Musoke, Peter Opio and Per Schøning DocumentsEnergy and Poverty A feasibility study on statistics on access and use of energy in Uganda Astrid L. Mathiassen, John B. Musoke, Peter Opio and Per Schøning Energy and Poverty A feasibility study on statistics on access and use of energy in Uganda Abstract The overall Uganda Policy on eradication of poverty as well as the energy specific policy includes strategies and targets for how to develop energy access and use. Numerous indicators are developed with the objective of providing a tool for monitoring of how well the policy targets are achieved. Timely and reliable information from statistical and administrative sources is urgently needed in order to determine these indicators and thereby to enable for monitoring of policy impacts and guidance for further development. This paper documents the findings and gives recommendations from a study with the objective to assess the available energy related statistics in Uganda in an attempt to link energy statistics to the country's poverty situation. The study was undertaken by Statistics Norway (SN) in close cooperation with the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) during a SN mission to UBOS May 23rd to June 10th, 2005. The Norwegian Government funded the project. The study identifies at least 4 major challenges to overcome: 1) To assemble and harmonize already existing information on energy from a multitude of sources and make it more easily accessible to the users. 2) To further improve the specification of parameters collected in order to fill possible gaps of information and to ensure a core set of information with regular intervals of updates that links the statistics to the policy indicators. -

Who and Why? Understanding Rural Out-Migration in Uganda

Article Who and Why? Understanding Rural Out-Migration in Uganda Samuel Tumwesigye 1,2,* , Lisa-Marie Hemerijckx 1 , Alfonse Opio 3, Jean Poesen 1,4 , Matthias Vanmaercke 1,5, Ronald Twongyirwe 2 and Anton Van Rompaey 1 1 Division of Geography and Tourism, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200E, 3001 Heverlee, Belgium; [email protected] (L.-M.H.); [email protected] (J.P.); [email protected] (M.V.); [email protected] (A.V.R.) 2 Department of Environment and Livelihoods Support Systems, Faculty of Interdisciplinary Studies, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara P.O. Box 1410, Uganda; [email protected] 3 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Gulu University, Gulu P.O. Box 166, Uganda; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Earth Sciences and Spatial Management, Maria-Curie Sklodowska University, Krasnicka 2D, 20-718 Lublin, Poland 5 Department of Geography, UR SPHERES, University of Liège, 4000 Liege, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Rural–urban migration in developing countries is considered to be a key process for sustainable development in the coming decades. On the one hand, rural–urban migration can contribute to the socioeconomic development of a country. On the other hand, it also leads to labor transfer, brain-drain in rural areas, and overcrowded cities where planning is lagging behind. In order to get a better insight into the mechanisms of rural–urban migration in developing countries, Citation: Tumwesigye, S.; this paper analyzes motivations for rural–urban migration from the perspective of rural households Hemerijckx, L.-M.; Opio, A.; Poesen, in Uganda. -

Ntungamo District HRV Profile.Pdf

Ntungamo District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 NTUNGAMO DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE a ACKNOWLEDGEMENT On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Odong Martin, Disaster Management Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/ DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to Ntungamo District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees NTUNGAMO DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The multi-hazard vulnerability profile outputs from this assessment was a combination of spatial modeling using socio-ecological spatial layers (i.e. DEM, Slope, Aspect, Flow Accumulation, Land use, vegetation cover, hydrology, soil types and soil moisture content, population, socio-economic, health facilities, accessibility, and meteorological data) and information captured from District Key Informant interviews and sub-county FGDs using a participatory approach. -

City Research Online

Keeble, R. (1996). The Gulf War myth: a study of the press coverage of the 1991 Gulf conflict. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) City Research Online Original citation: Keeble, R. (1996). The Gulf War myth: a study of the press coverage of the 1991 Gulf conflict. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/7932/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. The Gulf war myth A study of the press coverage of the 1991 Gulf conflict by Richard Keeble PhD in Journalism May 1996; Department of Journalism, City University, London CONTENTS Abstract ix Acknowledgements x Introduction xi-iii A.1 The war problematic xi -

District Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profile for Isingiro District

District Multi-hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profile for Isingiro District District Multi-hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profile a b District Multi-hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profile Acknowledgement On behalf of office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this hazard, risk and vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district hazard, risk and vulnerability profiles for the South Western districts which are Isingiro, Kamwenge, Mbarara, Rubirizi and Sheema. I especially extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Disaster Preparedness and Management in Office of the Prime Minister, under the leadership of Mr. Martin Owor - Commissioner Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management and Mr. Gerald Menhya - Assistant Commissioner Disaster Preparedness for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine - Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer, Nyangoma Immaculate - Disaster Preparedness Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR Specialists): Mr. Nsiimire Peter and Mr. Nyarwaya Amos who gathered the information and compiled this document are applauded. Our gratitude goes to the UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Gilbert Anguyo, Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, Mr. Janini Gerald and Mr. Ongom Alfred for providing valuable technical support in the organization of the exercise. My appreciation also goes to the District Teams: 1. Isingiro District: Mr. Bwengye Emmanuel – Ag. District Natural Resources Officer, Mr. Kamoga Abdu - Environment Officer and Mr. Mukalazi Dickson - District Physical Planner. 2. Kamwenge District: Mr. -

Attitudes, Practices and Knowledge of Communities Towards Climate

African Social Science Review Volume 10 | Number 1 Article 3 May 2019 Attitudes, Practices and Knowledge of Communities Towards Climate Change Around Lake Mburo National Park Uganda: A Gender Centered Analysis Judith Irene Nagasha Makerere University, [email protected] Michael Ocaido Makerere University, Uganda, [email protected] Elizabeth Kaase-Bwanga Makerere University, Uganda, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.tsu.edu/assr Recommended Citation Nagasha, Judith Irene; Ocaido, Michael; and Kaase-Bwanga, Elizabeth (2019) "Attitudes, Practices and Knowledge of Communities Towards Climate Change Around Lake Mburo National Park Uganda: A Gender Centered Analysis," African Social Science Review: Vol. 10 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.tsu.edu/assr/vol10/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Scholarship @ Texas Southern University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African Social Science Review by an authorized editor of Digital Scholarship @ Texas Southern University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attitudes, Practices and Knowledge of Communities Towards Climate Change Around Lake Mburo National Park Uganda: A Gender Centered Analysis Cover Page Footnote I would like to acknowledge the funder of this research; Swedish International Development Agency(SIDA); Mak-Sida Bilateral Project. - Codesria college of mentors -My supervisory team This article is available in African Social -

Uganda National Roads Network

UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS NETWORK REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Musingo #" !P Kidepo a w K ± r i P !P e t Apoka gu a K m #" lo - g - L a o u k - #" g u P i #" n d Moyo!P g o i #"#" - t #"#" N i k #" KOBOKO M e g a #" #" #" l Nimule o #"!P a YUMBE #" u!P m ng m o #" e #" Laropi i #" ro ar KAABONG #" !P N m K #" (! - o - te o e om Kaabong#"!P g MOYO T c n o #" o #" L be Padibe !P - b K m !P LAMWO #" a oboko - Yu Yumbe #" om r K #" #" #" O #" Koboko #" #" - !P !P o Naam REGIONS AND STATIONS Moy n #" Lodonga Adjumani#" Atiak - #" Okora a #" Obongi #" !P #" #" a Loyoro #" p #" Ob #" KITGUM !P !P #" #" ong !P #" #" m A i o #" - #" - K #" Or u - o lik #" m L Omugo ul #" !P u d #" in itg o i g Kitgum t Maracha !P !P#" a K k #" !P #" #"#" a o !P p #" #" #" Atiak K #" e #" (!(! #" Kitgum Matidi l MARACHA P e - a #" A #"#" e #" #" ke d #" le G d #" #" i A l u a - Kitgum - P l n #" #" !P u ADJUMANI #" g n a Moyo e !P ei Terego b - r #" ot Kotido vu #" b A e Acholibur - K o Arua e g tr t u #" i r W #" o - O a a #" o n L m fe di - k Atanga KOTIDO eli #" ilia #" Rh #" l p N o r t h #"#" B ino Rhino !P o Ka Gulu !P ca #" #"#" aim ARUA mp - P #" #" !P Kotido Arua #" Camp Pajule go #" !P GULU on #" !P al im #" !PNariwo #" u #" - K b A ul r A r G de - i Lira a - Pa o a Bondo #" Amuru Jun w id m Moroto Aru #" ctio AMURU s ot !P #" n - A o #" !P A K i !P #" #" PADER N o r t h E a s t #" Inde w Kilak #" - #" e #" e AGAGO K #"#" !P a #" #" #" y #" a N o #" #" !P #" l w a Soroti e #"#" N Abim b - Gulu #" - K d ilak o b u !P #" Masindi !P i um !P Adilang n - n a O e #" -

Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty Alleviation: the Case of Uganda Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty Alleviation: the Case of Uganda

Forests, livelihoods and poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda Forests, livelihoods and poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda G. Shepherd and C. Kazoora with D. Mueller Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2013 The Forestry Policy and InstitutionsWorking Papers report on issues in the work programme of Fao. These working papers do not reflect any official position of FAO. Please refer to the FAO Web site (www.fao.org/forestry) for official information. The purpose of these papers is to provide early information on ongoing activities and programmes, to facilitate dialogue and to stimulate discussion. The Forest Economics, Policy and Products Division works in the broad areas of strenghthening national institutional capacities, including research, education and extension; forest policies and governance; support to national forest programmes; forests, poverty alleviation and food security; participatory forestry and sustainable livelihoods. For further information, please contact: Fred Kafeero Forestry Officer Forest Economics, Policy and Products Division Forestry Department, FAO Viale Delle terme di Caracalla 00153 Rome, Italy Email: [email protected] Website: www.fao.org/forestry Comments and feedback are welcome. For quotation: FAO.2013. Forests, Livelihoods and Poverty alleviation: the case of Uganda, by, G. Shepherd, C. Kazoora and D. Mueller. Forestry Policy and Institutions Working Paper No. 32. Rome. Cover photo: Ankole Cattle of Uganda The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression af any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.