Field Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8 Days, 7 Nights Autumn2019 Istanbul & Bursa & Yalova Package

GURTOUR 8 D A Y S , 7 NIGHTS A U T U M N 2 0 1 9 I S T A N B U L & BURSA & YALOVA PACKAGE 8 Days Package (Valid : 01 Nov 19 – 01 Mar 20) (EXCLUDING : 27 DEC 19 - 03 JAN 20) “Bursa’s roots can be traced back to 5200 B.C., the year the area was first settled. What is now Turkey’s fourth-largest city swapped hands between the Greek, Bithynia, and Roman Empires before it became the first major capital of the Ottoman Empire between 1335 and 1363. 480 EUR PER PERSON / DBL Program: Day 01 : Arrive IST airport & transfer to hotel. Day 01: Arrive IST/SAW airport & transfer to Hotel. Overnight at Istanbul Day 02: Half Day Istanbul City Tour. Overnight at Istanbul Day 03: Istanbul hotel to Bursa hotel transfer (by speed ferry). Overnight at Bursa Day 04: Full Day Bursa Cable Car Tour with Lunch. Overnight at Bursa Day 05: Full Day Yalova Tour with Lunch. Transfer Yalova hotel. Overnight at Bursa Day 06: Bursa Hotel to Istanbul Hotel Transfer (by speed ferry). Overnight at Istanbul Day 07: Half Day Bosphorus Cruise Tour. Overnight at Istanbul Day 08: Free time until transfer to IST/SAW airport for homebound flight. BURSA CABLE CAR TOUR With Lunch YALOVA THERMAL TOUR With Lunch Cable Car, Uludag Mountain, Green Mosque Sudusen Waterfalls, Gokcedere Thermal & Tomb, Kircilar Leather Factory, Turkish Village, Shopping Outlet DelightFactory, Cinar Tree (600 Years Old) '' The city of Bursa, southeast of the Sea of Marmara, lies on the lower slopes of Mount Uludağ (Mt. -

Geothermal Application Experiences in Turkey

GEOTHERMAL APPLICATION EXPERIENCES IN TURKEY Orhan Mertoglu, Nilgun Bakir, Tevfik Kaya ORME Jeotermal A.S., Ankara/Turkey; Hosdere Cad. 190/7-8-12,Cankaya, [email protected] Keywords: Turkey, geothermal heating, balneology, electricity, mineral recovery Abstract Utilization area of geothermal energy is mostly focussed on direct use applications in Turkey. Today 61.000 residences equivalence is being heated geothermally (665 MWt, including residences, thermal facilities, 565.000 m2 greenhouse heating). Moreover, with the balneological utilisation of geothermal fluids in 195 spa’s (327 MWt), the geothermal direct use capacity is 992 MWt. ORME Geothermal Inc has completed the engineering designs of nearly 300.000 residences equivalence geothermal district heating system. 170 geothermal fields (Figure 1) have been explored in Turkey. There is a single flash power plant with 20,4 MWe installed capacity. A liquid CO2 and dry ice production factory is integrated to this power plant. A binary cycle geothermal power plant with an installation capacity of 25 MWe is going to be constructed at Aydin/Germencik. The proven geothermal heat capacity according to the existing geothermal wells and natural discharges is 3132 MWt [1]. 1. INTRODUCTION There are 11 city based geothermal district heating systems in Turkey. These geothermal district heating systems have been constructed since 1987 and many development has been achieved in technical and economical aspects. The rapid development of geothermal district heating systems in Turkey is mostly depending on; - construction of suitable geothermal district heating systems according to Turkey’s conditions, - participation of the consumers to the geothermal district heating investments by about 50 % without any direct financing refund, - geothermal heating is about % 50-70 cheaper than natural gas heating. -

Investigation of Outdoor Gamma Dose Rates in Yalova, Turkey

Avrupa Bilim ve Teknoloji Dergisi European Journal of Science and Technology Sayı 18, S. 568-573, Mart-Nisan 2020 No. 18, pp. 568-573, March-April 2020 © Telif hakkı EJOSAT’a aittir Copyright © 2020 EJOSAT Araştırma Makalesi www.ejosat.com ISSN:2148-2683 Research Article Investigation of Outdoor Gamma Dose Rates in Yalova, Turkey Kübra Bayrak1, Zeki Ünal Yümün2*, Merve Çakar3 1Akdeniz University, Faculty of Science, Physics Department, Antalya, Turkey 2Namik Kemal University, Corlu Engineering Faculty, Environmental Engineering Dep., Tekirdag, Turkey 3yildiz Technical University, Faculty of Arts And Sciences, Physics Department, Davutpasa Campus, 34220 Esenler, Istanbul, Turkey (First received 8 February 2020 and in final form 17 March 2020) (DOI: 10.31590/ejosat.686668) ATIF/REFERENCE: Bayrak, K., Yümün, Z. Ü. & Çakar, M. (2020). Investigation of Outdoor Gamma Dose Rates in Yalova, Turkey. European Journal of Science and Technology, (18), 568-573. Abstract Radioactivity measurements were performed, at the Yalova (Turkey), part of the Marmara Sea, for natural radiation using a scintillation detector SP6 (via using portable counter ESP2, Eberline). Based on the measurement results, the lowest outdoor gamma concentration was calculated to 27.70 nGy/h while the highest one calculated to 66.00 nGy/h. And, the average of the measured gamma dose rates calculated to 48.13 nGy/h while the annual effective dose equivalent was calculated to 59.02 μSv/y. Mean value of excess lifetime cancer risk also obtained 2.07 10-4 from using measurement area. The results checked against the world average determined by UNSCEAR. It was concluded that the calculated gamma dose values in Yalova are below the world average. -

Increased Funding and Citizen Support Give Birth to a Blueprint for Digital Transformation of Midsized Turkish City

Case Study Increased Funding and Citizen Support Give Birth to a Blueprint for Digital Transformation of Midsized Turkish City With half the population of Yalova Province living in the city of the Executive Summary same name, the municipality has drawn up an ambitious e-transforma- CUSTOMER NAME tion roadmap for increased use of Information and Communications Municipality of Yalova, Turkey Technology and broadband rollout, with an e-governance model to INDUSTRY accelerate economic progress and improve citizen services. Public Sector Business Challenges BUSINESS CHALLENGES • Create job opportunities by pro- Situated on a peninsula in the Sea of Marmara, some 40 miles to the moting economic development southeast of Istanbul, Yalova has enjoyed separate administrative status through ICT from Istanbul since 1995. The province has more than 185,000 inhabit- • Improve health and education services, and build a new hospital ants, half of whom are concentrated in Yalova city. Bound by a triangle of • Become an e-government larger industrial centers, Yalova is a popular tourist destination and sees pilot city in Turkey and an EU its numbers double in summer. Other principal industries are education Knowledge Society Center of and farming, and Yalova is ranked 13 among Turkish cities by GDP. Excellence Hit hard by the 1999 earthquake, which killed 14,000 people across north- SOLUTIONS eastern Turkey and left thousands more homeless, Yalova has worked • Implement productivity monitor- ing, mobile working, and hard to restore and improve its economic fortunes. After preliminary steps performance management tools toward an e-government, Mayor Barbaros Binicioglu decided that Yalova’s • Automate health and education future depended on more substantial Information and Communications services; integrate an e-govern- Technology (ICT) investments. -

Turkey Earthquake Hazard Map

Public Disclosure Authorized TURKISH ELECTRICITY TRANSMISSION CORPORATION DIRECTORATE GENERAL Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 380 kV ÇİFTLİKKÖY GIS SS (GAS INSULATED SYSTEM SUBSTATION) Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL and SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN PROVINCE OF YALOVA, ÇİFTLİKKÖY DISTRICT ANKARA – DECEMBER 2019 General Directorate of the Turkish Electricity Transmission Name of Project Owner: Corporation Nasuh Akar Mah. Türkocağı Cad No: 2 Çankaya, Address of Project Owner : Ankara Phone Number : +90 (312) 203 86 11 Fax Number : +90 (312) 203 87 17 380 kV ÇİFTLİKKÖY GIS SS (GAS INSULATED SYSTEM SUBSTATION) Name of Project ENVIRONMENTAL and SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Address of Site Selected for the Province of Yalova, Çiftlikköy District, İlyasköy Project Neighborhood i 380 kV ÇİFTLİKKÖY GIS ESMP TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No Contents i List of Tables ii List of Figures ii List of Annexes iii 1.PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................. 1 1.1 General Description of the Project ......................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope of Project ..................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Project Area............................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Technical Information on the Project ..................................................................... 7 1.5 Places with High Landscape Value, -

Frictional Strength of North Anatolian Fault in Eastern Marmara Region Ali Pınar* , Zeynep Coşkun, Aydın Mert and Doğan Kalafat

Pınar et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2016) 68:62 DOI 10.1186/s40623-016-0435-z FULL PAPER Open Access Frictional strength of North Anatolian fault in eastern Marmara region Ali Pınar* , Zeynep Coşkun, Aydın Mert and Doğan Kalafat Abstract Frequency distribution of azimuth and plunges of P- and T-axes of focal mechanisms is compared with the orientation of maximum compressive stress axis for investigating the frictional strength of three fault segments of North Anato- lian fault (NAF) in eastern Marmara Sea, namely Princes’ Islands, Yalova–Çınarcık and Yalova–Hersek fault segments. In this frame, we retrieved 25 CMT solutions of events in Çınarcık basin and derived a local stress tensor incorporating 30 focal mechanisms determined by other researches. As for the Yalova–Çınarcık and Yalova–Hersek fault segments, we constructed the frequency distribution of P- and T-axes utilizing 111 and 68 events, respectively, to correlate the geometry of the principle stress axes and fault orientations. The analysis yields low frictional strength for the Princes’ Island fault segments and high frictional strength for Yalova–Çınarcık, Yalova–Hersek segments. The local stress ten- sor derived from the inversion of P- and T-axes of the fault plane solutions of Çınarcık basin events portrays nearly horizontal maximum compressive stress axis oriented N154E which is almost parallel to the peak of the frequency dis- tribution of the azimuth of the P-axes. The fitting of the observed and calculated frequency distributions is attained for a low frictional coefficient which is about μ 0.1. Evidences on the weakness of NAF segments in eastern Marmara Sea region are revealed by other geophysical≈ observations. -

Socio-Economic Structure of the Population in Yalova

УПРАВЛЕНИЕ И ОБРАЗОВАНИЕ MANAGEMENT AND EDUCATION TOM V (2) 2009 VOL. V (2) 2009 SOCIO-ECONOMIC STRUCTURE OF THE POPULATION IN YALOVA Mesut Doğan СОЦИО-ИКОНОМИЧЕСКАТА СТРУКТУРА ПОПУЛАЦИЯТА В ЯЛОВА Месут Доган ABSTRACT: The population is an extremely active phenomenon and one of the factors in the development of the settlement areas. Population structure is closely related with political, economic and social circumstances. In addition, developments in rural and urban population are also indications of the development levels. Popula- tion movements are quite important in our study area. Especially, Yalova, close to the metropolis Istanbul and to important trade centers such as Kocaeli and Bursa and with favorable living conditions is an area where signifi- cant changes take place in populational features. Key Words: Yalova, Population, Social Structure, Development, Green-Blue Line Introduction luck,1910,s.69) . The area was invaded by the Frigians in 1200s BC, settled by the Britons - Yalova situated on the northern side of the which became dominant in the eastern part of the Samanlı Mountains is surrounded by the Mar- Marmara Sea by passing from Thrace to Anatolia mara Sea in the north and west, by Gemlik Bay in the 7th century BC – and then given to the in the south and by Kocaeli in the east. (Graphic Macedonians as a gift somewhere between 230 1) It is generally of a mountanous nature apart and 182 BC. Yalova and the environs, which from the planes consisting of coastal plains and became a district of Roman Empire in 74 BC, deltaic plains located on the eastern side of Ya- remained in the boarders of the Eastern Roman lova Empire after the split of the Roman Empire. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached Copy Is Furnished to the Author for Internal Non-Commerci

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Tectonophysics 510 (2011) 17–27 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tectonophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto Review Article Evolution of the seismicity in the eastern Marmara Sea a decade before and after the 17 August 1999 Izmit earthquake H. Karabulut a, J. Schmittbuhl b,⁎, S. Özalaybey c, O. Lengliné b, A. Kömeç-Mutlu a, V. Durand d, M. Bouchon d, G. Daniel b,e, M.P. Bouin f a Bogaziçǐ University, Kandilli Observatory and Earthquake Research Institute, Istanbul, Turkey b IPGS, Université de Strasbourg/EOST, CNRS, France c TUBITAK, Marmara Research Center, Gebze-Kocaeli, Turkey d Isterre, Université de Grenoble, CNRS, Grenoble, France e Université de Franche Comté, Besançon, France f Observatoire Volcanologique et Sismologique de la Guadeloupe, France article info abstract Article history: We review the long term evolution of seismicity in the eastern Marmara Sea over a decade, before and after Received 31 March 2011 the 1999 Mw 7.6 Izmit earthquake. -

View Full Text Article

BİTKİ KORUMA BÜLTENİ 2014, 54(4):303-309 ISSN 0406-3597 First record of the Oriental chestnut gall wasp, Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) in Turkey Gürsel ÇETĠN1 Erdal ORMAN1 Zühtü POLAT1 ÖZET Kestane gal arısının, Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) Türkiye’de ilk kaydı Dünyada, kestane çeĢitlerinde en zararlı türlerinden biri olarak kabul edilen Kestane gal arısı, Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae), Türkiye‟de ilk kez 2014 yılı nisan ayının son haftasında kaydedilmiĢtir. Zararlının Marmara Bölgesinde, Yalova ve Bursa illerindeki bazı kestane bahçeleri ile yaklaĢık 2000 ha ormanlık alanda bulunduğu belirlenmiĢtir. Avrupa karantina listesinde bulunan zararlı aynı zamanda Türkiye‟nin zirai karantina listesinde de yer almaktadır. Anahtar kelimeler: Kestane gal arısı; Dryocosmus kuriphilus; Castanea sativa; Türkiye ABSTRACT Oriental chestnut gall wasp, Dryocosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) considered to be one of the most harmful pests of sweet chestnut varieties in the world has been recorded at the end of week of April 2014 for the first time in Turkey. It was observed in a few chestnut groves and in some forest areas, about 2000 ha in Yalova and Bursa province of the Marmara Region, Turkey. It is on quarantine species lists in Europe as well as in Turkey. Keywords: Oriental chestnut gall wasp, Dryocosmus kuriphilus, Castanea sativa, Turkey INTRODUCTION Chestnut cultivar grown in Turkey located in the Mediterranean basin is European chestnut; Castanea sativa Miller, as in other countries located the Mediterranean basin (SubaĢı 2004). Chestnut is an important income source for forest villagers in Turkey. Annual chestnut production of Turkey is 60.000 tons in 40.000 ha area (Anonymous 2010). -

HATAY GUIDE for Investors

HATAY GUIDE For Investors www.dogaka.gov.tr Hatay Awaits Your Investments CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ...............................................2 PROMINENT SECTORS IN HATAY PROVINCE..................4 AGRICULTURE ................................................................5 INDUSTRY.....................................................................10 CULTURE AND TOURISM ............................................25 ENERGY.......................................................................32 LOGISTICS....................................................................36 FOREIGN TRADE............................................................38 ONGOING PUBLIC INVESTMENTS IN HATAY ................41 WHY HATAY?.................................................................46 INCENTIVES AND SUPPORTS ......................................50 3 GENERAL INFORMATION General One of the earliest settlement areas in human history, Hatay is a province of fellow Information ship and tolerance, where different cultures and beliefs have existed from the past to the present and which hosted many civilizations. Earliest findings related to humans in the region date back to 100.000s B.C. Hatay remained within the boundaries of Syria with the agreement signed between Turkey and France in 1921, later and in 1938 State of Hatay was founded and in 23 July 1939 the state joined Turkey. Hatay is located in Southern Turkey, on the eastern shores of Gulf of Iskenderun. It is surrounded by the Mediterranean in the west, Syria in the south and east, -

Impact of Syria's Refugees Southern Turkey

THE IMPACT OF SYRIA’S REFUGEES ONSOUTHERN TURKEY REVISED AND UPDATED SONER CAGAPTAY POLICY FOCUS 130, REVISED and UPDATED JULY 2014 THEIMPACT OF SYRIA’S REFUGEES ONSOUTHERN TURKEY Soner Cagaptay with Bilge Menekse the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org Contents The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v not necessarily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. 1 INTRODUCTION 1 ■ ■ ■ 2 TURKEY’S BORDER PROVINCES NEAR SYRIA 6 3 SHIFTS IN THE ETHNIC BALANCE OF THE BORDER PROVINCES 16 4 ECONOMICS 23 5 CONCLUSION 28 ABOUT THE AUTHOR 32 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publi- cation may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First publication October 2013; revised and updated July 2014. Maps © 2013, 2014 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy REGISTERED REFUGEES IN AND OUT OF CAMPS 14–15 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: (top) Newly arrived Syrian refugees are seen at Ceylanpinar refugee camp near the border town of Ceylanpinar, Sanliurfa province, November 2012 (REUTERS/Murad Sezer); (bottom) Turkish Red Crescent tents at a refugee camp in Yayladagi, Hatay province, June 2011 (REUTERS/Umit Bektas). Cover design: 1000colors.org Acknowledgments The author would like to thank the Institute’s Turkish Research Program staff Bilge Menekse and Merve Tahiroglu for their assistance with this policy paper. -

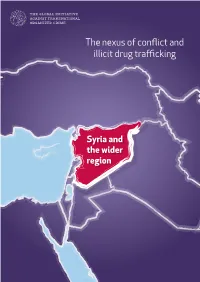

The Nexus of Conflict and Illicit Drug Trafficking Syria and the Wider Region a N E T W O R K T O C O U N T E R N E T W O R K S

The nexus of conflict and illicit drug trafficking SyriaSyria andand thethe widerwider regionregion 1 The nexus of conflict and illicit drug trafficking Syria and the wider region A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS 2 The nexus of conflict and illicit drug trafficking Syria and the wider region The nexus of conflict and illicit drug trafficking Syria and the wider region November 2016 © 2016 Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.globalinitiative.net Acknowledgments The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GI) is grateful to the national and international in- stitutions which shared their knowledge and data with the report team, including though not limited to, Europol, Interpol, Turkish National Police Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime, the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, the United Kingdom National Crime Agency, Austrian BKA, Bulgarian Customs and Counter Narcotics law enforcement, Hellenic Counter narcotics police, German BKA and ZKA, Italy, DEA Lebanon, Dutch KLPD, Guarda Civil Spain, the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq. Regional organisations con- tributing to this report include the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Southeast European Law Enforcement Centre (SELEC) to whom we are most indebted. This report was drafted and prepared by Ben Crabtree. The preparation of this report benefited from the financial contributions of Norway.