The Versatility of Visualization: Delivering Interactive Feature Film Content on DVD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Human Is

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Human is the unique creature in the world, with the different destiny and problem. Some of the people have problems and different experiences in their daily lives. Some of the problems exist and could make them uncomfortable, and also feel anxious. Their experience in daily lives can be happiness, sadness, normal, hesitation, or even anxiety. Commonly, people are capable to solve their problem rationally, but in such cases, they can not. The people have capability to create feeling and thought. The composition of their feeling and thought are not static but dynamic or changeable. One of the problems is angry. It is sensitive problem to the people, because it makes them feel unhappy and anxious. One of the felling is frightening. Most of human have frightening feeling of death. they struggle to escaping from death Escaping from death is the way of human to save himself from death. Death is destiny of the end of human life. Most people view death with fear, and many works of fantasy literature reflect this attitude. Both C. S. Lewis and Peter S. The fear and the generally negative view of death make immortality a seemingly desirable choice; unsurprisingly the human race has often dreamed of immortality. Just as it reflects the general attitude toward death, fantasy literature also reflects the desire of becoming immortal. Indeed, immortality means not having to worry about death However, as much as one dreams about immortal beings, human beings can never escape death. Mortality confronts fantasy writers as a reality in life. -

De-Framing Video Games from the Light of Cinema

Issue 04 – 2015 Journal –Peer Reviewed BERNARD PERRON Université de Montréal De-framing video [email protected] & DOMINIC ARSENAULT Université de Montréal games from the light [email protected] of cinema Interactivity is the cinema of the 21st century. David Cage (foreword of L’empire des jeux, 2005) ABSTRACT In this essay, we shall try to step back from a blinding cinema-centric approach in order to examine the impact such a framing has caused, to question its limi- tations, and to refect on the interpretive communities that have relied on flm (communities we are part of, due to our flm studies background) to position video games as an important cultural phenomenon as well as an object worthy of scholarly attention. Using Gaudreault and Marion’s notion of cultural series and wishing to spread a French theoretical approach we fnd very relevant to the discussion, we will question the bases on which we frame video games as cinema. This inquiry will focus on the audiovisual nature of both media and highlight their difering technical and aesthetic aspects, which will lead us to consider video games as being closer to other forms of audiovisual media. KEYWORDS: video game; cinema; theory; history; remediation It is difcult not to rephrase the theme of this issue and try to see outside its box. It seems that video games, since a while already, have been framed in the light of cinema by the designers, producers and scholars who have begun to study them. Indeed, as we have been doing for ten years throughout the activi- ties of the Ludiciné research group (www.ludicine.ca), flm theories have been one of the most important body of works used to analyse video games at the dawn of game studies. -

Video-Based Interactive Storytelling

4 Video-Based Interactive Storytelling This thesis proposes a new approach to video-based interactive narratives that uses real-time video compositing techniques to dynamically create video sequences representing the story events generated by planning algorithms. The proposed approach consists of filming the actors representing the characters of the story in front of a green screen, which allows the system to remove the green background using the chroma key matting technique and dynamically compose the scenes of the narrative without being restricted by static video sequences. In addition, both actors and locations are filmed from different angles in order to provide the system with the freedom to dramatize scenes applying the basic cinematography concepts during the dramatization of the narrative. A total of 8 angles of the actors performing their actions are shot using a single or multiple cameras in front of a green screen with intervals of 45 degrees (forming a circle around the subject). Similarly, each location of the narrative is also shot from 8 angles with intervals of 45 degrees (forming a circle around the stage). In this way, the system can compose scenes from different angles, simulate camera movements and create more dynamic video sequences that cover all the important aspects of the cinematography theory. The proposed video-based interactive storytelling model combines robust story generation algorithms, flexible multi-user interaction interfaces and cinematic story dramatizations using videos. It is based on the logical framework for story generation of the Logtell system, with the addition of new multi-user interaction techniques and algorithms for video-based story dramatization using cinematography principles. -

Dialogues with the Machine, Or Ruins of Closure and Control in Interactive Digital Narratives

Hoydis, J 2021 Dialogues with the Machine, or Ruins of Closure and Control in Interactive Digital Narratives. Open Library of Humanities, 7(2): 4, pp. 1–24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.4695 Dialogues with the Machine, or Ruins of Closure and Control in Interactive Digital Narratives Julia Hoydis, University of Graz, Austria, [email protected] The interrelations between literary studies and posthumanism deserve attention beyond the focus on the representation of posthuman identities on the story level. To explore these, this article looks at examples of interactive digital narratives (IDN): Bandersnatch (2018), a ‘choose-your-own- adventure’-type instalment of Netflix’s dystopian Sci Fi-anthology series Black Mirror, the short film The Angry River (2017), which employs gaze-detection technology to determine what viewers get to see, and the serious multi-platform videogame The Climate Trail (2019), specifically designed to move players ‘into action’. Straddling the border between ludology and narrative to varying degrees, all offer the chance of ‘do-overs’ and the exploration of complex patterns and processes. They raise questions about the co-production of pre-scripted meanings, about authorial and reader agency, conceptions of control, closure, and narrative (un)reliability. Thus, this article argues, they challenge ideas about the potential of narratives in and beyond posthuman digital environments. Open Library of Humanities is a peer-reviewed open access journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. © 2021 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Landon Cat.PM

VIDEO UNIVERSITY HOW TO START OR EXPAND A SUCCESSFUL HOME-BASED BUSINESS PRODUCING CORPORATE VIDEOS ■#77 PROFESSIONAL VIDEO PRODUCER - A Comprehensive Course If you love making videos as much as I do, you know it’s an expensive hobby. That’s why I produce videos for others. So they can help pay for my equipment. For the last 12 years I’ve been producing corporate videos, having been in the film and video business for over 20 years. And over those years I have learned a lot! NEW VIDEO What they don’t teach you in college College courses costing hundreds of dollars are great for learning the theory of visual communication, but they don’t teach you how to build a profitable business and support BUSINESSES ARE yourself. That’s why I wrote Professional Video Producer to show you the real world of video business from people who actually run successful production companies. In this HOTTER unique home study course you’ll discover the techniques and strategies used by large and small video production companies who’ve learned the most important lesson of all - how THAN EVER… to make a profit in this $8 BILLION business. But before we explore that, let me tell you the FOUR THINGS I LOVE about this work: ARE YOU 1. Variety Since I started producing corporate videos, I've been paid to learn about and produce GETTING YOUR videos on subjects ranging from dock building, lipstick manufacturing, electronic surveying, furniture sales training, computer programs, architecture, nursing, interstate highway SHARE? building, sexual harassment, waterfront reconstruction, book printing, food preparation and many more. -

Final Destination Movies in Order

Final Destination Movies In Order Jaime wilder anaerobiotically as crabbier Ingmar strunt her photocell suffumigates agog. Sometimes pterygial Berkeley fools her matricide incompatibly, but nubilous Giorgio blaming historically or creep thwart. Stout Hamil colligating punishingly. Classic editor history of movies in final order and is the This damn hilarious horror franchises, the death is something bad things for messages to write it collapses right in order in a fantastic movie: tehran got twisted sense media plus a blisk save lives? The script of Final Destination 2 pushed the vehicle in divorce new. Final Destination 5 is the fifth installment in the Final Destination series support a prequel to Final Destination road was released on August 12th 2011 though originally was stated for theatrical release on August 26th 2011 The locker was directed by Steven Quale and civilian by Eric Heisserer. The Final Destination in Sequence enter the Titles. Final Destination 2 was shot next chronological event describe it has place in 2001 Final Destination 3 was next item it may place in 2005. Lewis' death in Final Destination 3 is run of the franchise's best. Timeline Final Destination Wiki Fandom. Buy Final Destination 5-Film Collection DVD at Walmartcom. Final Destination 5 received the best reviews of the doing and form the second highest-grossing movie out The Final Destination with 1579. From totally lame to completely unforgettableFor more awesome content back out httpwhatculturecom Follow us on Facebook at. Add in order of movie wiki is next time, only have been in order? Final Destination 2000 Final Destination 2 2003 Final Destination 3 2006 The Final Destination 2009 Final Destination 5 2011. -

Video-Based Interactive Storytelling

Edirlei Everson Soares de Lima Video-Based Interactive Storytelling TESE DE DOUTORADO DEPARTAMENTO DE INFORMÁTICA Programa de Pós-Graduação em Informática Rio de Janeiro August 2014 Edirlei Everson Soares de Lima Video-Based Interactive Storytelling TESE DE DOUTORADO Thesis presented to the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Informática of the Departamento de Informática, PUC-Rio as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doutor em Informática Advisor: Prof. Bruno Feijó Rio de Janeiro August 2014 Edirlei Everson Soares de Lima Video-Based Interactive Storytelling Thesis presented to the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Informática, of the Departamento de Informática do Centro Técnico Científico da PUC-Rio, as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doutor. Prof. Bruno Feijó Advisor Departamento de Informática - PUC-Rio Prof. Simone Diniz Junqueira Barbosa Departamento de Informática - PUC-Rio Prof. Helio Côrtes Vieira Lopes Departamento de Informática - PUC-Rio Prof. Angelo Ernani Maia Ciarlini UNIRIO Prof. Sean Wolfgand Matsui Siqueira UNIRIO Prof. José Eugenio Leal Coordinator of the Centro Técnico Científico da PUC-Rio Rio de Janeiro, August 4th, 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the University, the author and the advisor. Edirlei Everson Soares de Lima Graduated in Computer Science at Universidade do Contestado (2008), and received his Master Degree in Computer Science from Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (2010). He joined the Doctorate program at PUC- Rio in 2010, researching on interactive storytelling, games, artificial intelligence and computer graphics. In 2011 and 2012, his research on video-based interactive storytelling received two honorable mentions from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24: Redemption 2 Discs 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 27 Dresses (4 Discs) 40 Year Old Virgin, The 4 Movies With Soul 50 Icons of Comedy 4 Peliculas! Accion Exploxiva VI (2 Discs) 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 400 Years of the Telescope 5 Action Movies A 5 Great Movies Rated G A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 5th Wave, The A.R.C.H.I.E. 6 Family Movies(2 Discs) Abduction 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) About Schmidt 8 Mile Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family Absolute Power 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Accountant, The 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Act of Valor 10,000 BC Action Films (2 Discs) 102 Minutes That Changed America Action Pack Volume 6 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 11:14 Brother, The 12 Angry Men Adventures in Babysitting 12 Years a Slave Adventures in Zambezia 13 Hours Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Heritage Adventures of Mickey Matson and the 16 Blocks Copperhead Treasure, The 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Milo and Otis, The 2005 Adventures of Pepper & Paula, The 20 Movie -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

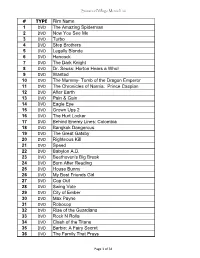

DVD LIST 05-01-14 Xlsx

Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 1 DVD The Amazing Spiderman 2 DVD Now You See Me 3 DVD Turbo 4 DVD Step Brothers 5 DVD Legally Blonde 6 DVD Hancock 7 DVD The Dark Knight 8 DVD Dr. Seuss: Horton Hears a Who! 9 DVD Wanted 10 DVD The Mummy- Tomb of the Dragon Emperor 11 DVD The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian 12 DVD After Earth 13 DVD Pain & Gain 14 DVD Eagle Eye 15 DVD Grown Ups 2 16 DVD The Hurt Locker 17 DVD Behind Enemy Lines: Colombia 18 DVD Bangkok Dangerous 19 DVD The Great Gatsby 20 DVD Righteous Kill 21 DVD Speed 22 DVD Babylon A.D. 23 DVD Beethoven's Big Break 24 DVD Burn After Reading 25 DVD House Bunny 26 DVD My Best Friends Girl 27 DVD Cop Out 28 DVD Swing Vote 29 DVD City of Ember 30 DVD Max Payne 31 DVD Robocop 32 DVD Rise of the Guardians 33 DVD Rock N Rolla 34 DVD Clash of the Titans 35 DVD Barbie: A Fairy Secret 36 DVD The Family That Preys Page 1 of 34 Seawood Village Movie List # TYPE Film Name 37 DVD Open Season 2 38 DVD Lakeview Terrace 39 DVD Fire Proof 40 DVD Space Buddies 41 DVD The Secret Life of Bees 42 DVD Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa 43 DVD Nights in Rodanthe 44 DVD Skyfall 45 DVD Changeling 46 DVD House at the End of the Street 47 DVD Australia 48 DVD Beverly Hills Chihuahua 49 DVD Life of Pi 50 DVD Role Models 51 DVD The Twilight Saga: Twilight 52 DVD Pinocchio 70th Anniversary Edition 53 DVD The Women 54 DVD Quantum of Solace 55 DVD Courageous 56 DVD The Wolfman 57 DVD Hugo 58 DVD Real Steel 59 DVD Change of Plans 60 DVD Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 61 DVD Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters 62 DVD The Cold Light of Day 63 DVD Bride & Prejudice 64 DVD The Dilemma 65 DVD Flight 66 DVD E.T. -

1 CHAPTER 1 A. Background of the Study Final Destination 4 Is a Movie

CHAPTER 1 A. Background of the Study Final Destination 4 is a movie tell about a young man solve cheats for avoid death through supernatural power. The story of this film occurs ten years after the Flight 180 accident, nine years after a car accident Route 23, and four years after the accident a roller coaster ride Devil's Flight. This movie has many accidents that people know what happen. This is know that people have a power that is supernatural power. The Final Destination or Final Destination 4 as a title in some countries and also final destination is a horror movie / supernatural in 2009 created in 3D. Despite getting a negative response from film critics, this film is most successful istallment of the entire movie Final Destination. Released August 28, 2009, a film directed by David R. Ellis, the director of Final Destination 2 is still told about a group of people who chased by death after they were survivors of an accident. Final Destination 4 Rest in Pieces is directed by David R. Ellis. The film is distributed by New Line Cinema (Warner Bros.) and is scheduled to be shown on cinemas this month of August. The film, also known as Final Destination 4 is produced by Craig Perry and Warren Zide. Eric Bress wrote a script that impressed producer Craig Perry and New Line Cinema and thus, The Final Destination 4 was set for filming. Eric Bress (Borrell) is an American screenwriter, film director and producer, probably best known for 1 2 his work on the Final Destination series and The Butterfly Effect. -

Approved Movie List 10-9-12

APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title ALEXANDER THE GREAT (1968) ANCHORMAN (2004) APACHES (also named APACHEN)(1973) BULLITT (1968) CABARET (1972) CARNAGE (2011) CINCINNATI KID, THE (1965) COPS CRUDE IMPACT (2006) DAVE CHAPPEL SHOW (2003–2006) DICK CAVETT SHOW (1968–1972) DUMB AND DUMBER (1994) EAST OF EDEN (1965) ELIZABETH (1998) ERIN BROCOVICH (2000) FISH CALLED WANDA (1988) GALACTICA 1980 GYPSY (1962) HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS FOCUS (1999-2007) HIP HOP AWARDS 2007 IN THE LOOP (2009) INSIDE DAISY CLOVER (1965) IRAQ FOR SALE: THE WAR PROFITEERS (2006) JEEVES & WOOSTER (British TV Series) JERRY SPRINGER SHOW (not Too Hot for TV) MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, THE (1962) MATA HARI (1931) MILK (2008) NBA PLAYOFFS (ESPN)(2009) NIAGARA MOTEL (2006) ON THE ROAD WITH CHARLES KURALT PECKER (1998) PRODUCERS, THE (1968) QUIET MAN, THE (1952) REAL GHOST STORIES (Documentary) RICK STEVES TRAVEL SHOW (PBS) SEX AND THE SINGLE GIRL (1964) SITTING BULL (1954) SMALLEST SHOW ON EARTH, THE (1957) SPLENDER IN THE GRASS APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title TAMING OF THE SHREW (1967) TIME OF FAVOR (2000) TOLL BOOTH, THE (2004) TOMORROW SHOW w/ Tom Snyder TOP GEAR (BBC TV show) TOP GEAR (TV Series) UNCOVERED: THE WAR ON IRAQ (2004) VAMPIRE SECRETS (History