Preliminary Draft No. 9 (September 4, 2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles Lightened Scrutiny

VOLUME 124 MARCH 2011 NUMBER 5 © 2011 by The Harvard Law Review Association ARTICLES LIGHTENED SCRUTINY Bert I. Huang TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1111 I. DEFERENCE ADRIFT? ........................................................................................................... 1116 A. The Judges’ Hypothesis .................................................................................................... 1118 B. In Search of Evidence ...................................................................................................... 1119 II. A NATURAL EXPERIMENT: “THE SURGE” ..................................................................... 1121 A. The Unusual Origins of the Surge ................................................................................... 1122 B. Toward a Causal Story ..................................................................................................... 1123 C. A Second Experiment ....................................................................................................... 1126 III. FINDINGS: LIGHTENED SCRUTINY ............................................................................... 1127 A. The Data ............................................................................................................................. 1127 B. Revealed Deference .......................................................................................................... -

Notice of Proposed Second Administrative Settlement and Request for Public Comment

http://frwebgate3.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin.. .cID=7723205640+0+0+0&WAISaction=retrieve Superfund Records Confer [Federal Register: September 10, 2002 (Volume 67, Number 175)] ol 11: faff <&&*>! [Notices] BREAK: [Page 57426-57429] OTHER: From the Federal Register Online via GPO Access [wais.access.gpo.gov] [DOCID:frlOse02-81] ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY [FRL-7373-4] Proposed Second Administrative Cashout Settlement Under Section 122(g) of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act; In Re: Beede Waste Oil Superfund Site, Plaistow, NH AGENCY: Environmental Protection Agency. ACTION: Notice of proposed second administrative settlement and request for public comment. [[Page 57427]] SUMMARY: In accordance with section 122(i) of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. 9622(i), notice is hereby given of a proposed second administrative settlement for recovery of past and projected future response costs concerning the Beeda Waste Oil Superfund Site in Plaistow, New Hampshire with the settling parties listed in the Supplementary Information portion of this notice. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency--Region I (EPA) is proposing to enter into a second de minimis settlement agreement to address claims under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, as amended (^CERCLA11), 42 U.S.C. 9601 et seq. Notice is being published to inform the public of the proposed second settlement and of the opportunity to comment. This second settlement, embodied in a CERCLA section 122(g) Administrative Order on Consent C'AOC'1), is designed to resolve each settling party's liability at the Site for past work, past response costs and specified future work and response costs through covenants under sections 106 and 107 of CERCLA, 42 U.S.C. -

United States Court of Appeals

United States Court of Appeals Fifth Federal Judicial Circuit Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas Circuit Judges Priscilla R. Owen, Chief Judge ...............903 San Jacinto Blvd., Rm. 434 ..................................................... (512) 916-5167 Austin, Texas 78701-2450 Carl E. Stewart ......................................300 Fannin St., Ste. 5226 ............................................................... (318) 676-3765 Shreveport, LA 71101-3425 Edith H. Jones .......................................515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12505 ................................... (713) 250-5484 Houston, Texas 77002-2655 Jerry E. Smith ........................................515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12621 ................................... (713) 250-5101 Houston, Texas 77002-2698 James L. Dennis ....................................600 Camp St., Rm. 219 .................................................................. (504) 310-8000 New Orleans, LA 70130-3425 Jennifer Walker Elrod ........................... 515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12014 .................................. (713) 250-7590 Houston, Texas 77002-2603 Leslie H. Southwick ...............................501 E. Court St., Ste. 3.750 ........................................................... (601) 608-4760 Jackson, MS 39201 Catharina Haynes .................................1100 Commerce St., Rm. 1452 ..................................................... (214) 753-2750 Dallas, Texas 75242 James E. Graves Jr. ................................501 E. Court -

Yale Law School 2019–2020

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Yale Law School 2019–2020 Yale Law School Yale 2019–2020 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 115 Number 11 August 10, 2019 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 115 Number 11 August 10, 2019 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse Avenue, New Haven CT 06510. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. backgrounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, against any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 disability, status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 4th Floor, 203.432.0849. -

James Fishkin

James A. Fishkin Partner Washington, D.C. | 1900 K Street, NW, Washington, DC, United States of America 20006-1110 T +1 202 261 3421 | F +1 202 261 3333 [email protected] Services Antitrust/Competition > Merger Clearance > Merger Litigation: U.S. > James A. Fishkin combines both government and private sector experience within his practice, which focuses on mergers and acquisitions covering a wide range of industries, including supermarket chains and other retailers, consumer and food product manufacturers, internet- based firms, chemical and industrial gas firms, and healthcare firms. He has been a key participant in several of the most significant litigated antitrust cases in the last two decades that have set important precedents, including representing Whole Foods Market, Inc. in FTC v. Whole Foods Market, Inc. and the Federal Trade Commission in FTC v. Staples, Inc. and FTC v. H.J. Heinz Co. Mr. Fishkin has also played key roles in securing unconditional clearances for many high-profile mergers, including the merger of OfficeMax/Office Depot and Monster/HotJobs, and approval for other high-profile mergers after obtaining successful settlements, including the merger of Albertsons/Safeway. He also served as the court-appointed Divestiture Trustee on behalf of the Department of Justice in the Grupo Bimbo/Sara Lee bread merger. Mr. Fishkin has been recognized by Chambers USA, The Best Lawyers in America, The Legal 500 , and Benchmark Litigation for his antitrust work. Chambers USA notes that Mr. Fishkin “impresses sources with his ‘very practical perspective,’ with commentators also describing him as ‘very analytical.’” The Legal 500 states that Mr. -

Abundant Splits and Other Significant Bankruptcy Decisions

Abundant Splits and Other Significant Bankruptcy Decisions 38th Annual Commercial Law & Bankruptcy Seminar McCall, Idaho Feb. 6, 2020; 2:30 P.M. Bill Rochelle • Editor-at-Large American Bankruptcy Institute [email protected] • 703. 894.5909 © 2020 66 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 600 • Alexandria, VA 22014 • www.abi.org American Bankruptcy Institute • 66 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 600 • Alexandria, VA 22314 1 www.abi.org Table of Contents Supreme Court ........................................................................................................................ 4 Decided Last Term ........................................................................................................................... 5 Nonjudicial Foreclosure Is Not Subject to the FDCPA, Supreme Court Rules ............................. 6 Licensee May Continue Using a Trademark after Rejection, Supreme Court Rules .................. 10 Court Rejects Strict Liability for Discharge Violations ............................................................... 15 Supreme Court Decision on Arbitration Has Ominous Implications for Bankruptcy ................. 20 Decided This Term ......................................................................................................................... 24 Supreme Court Rules that ‘Unreservedly’ Denying a Lift-Stay Motion Is Appealable .............. 25 Supreme Court Might Allow FDCPA Suits More than a Year After Occurrence ....................... 28 Cases Argued So Far This Term .................................................................................................. -

Members by Circuit (As of January 3, 2017)

Federal Judges Association - Members by Circuit (as of January 3, 2017) 1st Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit Bruce M. Selya Jeffrey R. Howard Kermit Victor Lipez Ojetta Rogeriee Thompson Sandra L. Lynch United States District Court District of Maine D. Brock Hornby George Z. Singal John A. Woodcock, Jr. Jon David LeVy Nancy Torresen United States District Court District of Massachusetts Allison Dale Burroughs Denise Jefferson Casper Douglas P. Woodlock F. Dennis Saylor George A. O'Toole, Jr. Indira Talwani Leo T. Sorokin Mark G. Mastroianni Mark L. Wolf Michael A. Ponsor Patti B. Saris Richard G. Stearns Timothy S. Hillman William G. Young United States District Court District of New Hampshire Joseph A. DiClerico, Jr. Joseph N. LaPlante Landya B. McCafferty Paul J. Barbadoro SteVen J. McAuliffe United States District Court District of Puerto Rico Daniel R. Dominguez Francisco Augusto Besosa Gustavo A. Gelpi, Jr. Jay A. Garcia-Gregory Juan M. Perez-Gimenez Pedro A. Delgado Hernandez United States District Court District of Rhode Island Ernest C. Torres John J. McConnell, Jr. Mary M. Lisi William E. Smith 2nd Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Barrington D. Parker, Jr. Christopher F. Droney Dennis Jacobs Denny Chin Gerard E. Lynch Guido Calabresi John Walker, Jr. Jon O. Newman Jose A. Cabranes Peter W. Hall Pierre N. LeVal Raymond J. Lohier, Jr. Reena Raggi Robert A. Katzmann Robert D. Sack United States District Court District of Connecticut Alan H. NeVas, Sr. Alfred V. Covello Alvin W. Thompson Dominic J. Squatrito Ellen B. -

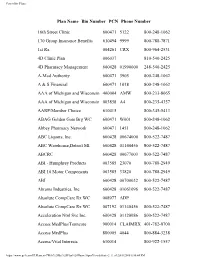

Powerline Plans

Powerline Plans Plan Name Bin Number PCN Phone Number 16th Street Clinic 600471 5122 800-248-1062 170 Group Insurance Benefits 610494 9999 800-788-7871 1st Rx 004261 CRX 800-964-2531 4D Clinic Plan 006037 810-540-2425 4D Pharmacy Management 600428 01990000 248-540-2425 A-Med Authority 600471 3905 800-248-1062 A & S Financial 600471 1018 800-248-1062 AAA of Michigan and Wisconsin 400004 AMW 800-233-8065 AAA of Michigan and Wisconsin 003858 A4 800-235-4357 AARP/Member Choice 610415 800-345-5413 ABAG Golden Gate Brg WC 600471 W001 800-248-1062 Abbey Pharmacy Network 600471 1451 800-248-1062 ABC Liquors, Inc. 600428 00674000 800-522-7487 ABC Warehouse,Detroit MI 600428 01140456 800-522-7487 ABCRC 600428 00677003 800-522-7487 ABI - Humphrey Products 003585 23070 800-788-2949 ABI 10 Motor Components 003585 33820 800-788-2949 ABI 600428 00700032 800-522-7487 Abrams Industries, Inc. 600428 01061096 800-522-7487 Absolute CompCare Rx WC 008977 ADP Absolute CompCare Rx WC 007192 01140456 800-522-7487 Acceleration Ntnl Svc Inc. 600428 01120086 800-522-7487 Access MedPlus/Tenncare 900014 CLAIMRX 401-782-0700 Access MedPlus 880005 4044 800-884-3238 Access/Vital Interests 610014 800-922-1557 https://www.qs1.com/PLPlans.nsf/Web%20By%20Plan%20Name!OpenView&Start=2 (1 of 2)8/8/2006 6:50:44 PM Powerline Plans Accident Fund of Michigan 600428 00700054 800-522-7487 Accubank Mortgage Inc 600428 00672018 800-522-7487 Aclaim 005848 800-422-5246 ACMG Employers Health Plan 400004 ACM 800-233-8065 Acordia Sr Benefits Horizons 600428 00790015 800-522-7487 https://www.qs1.com/PLPlans.nsf/Web%20By%20Plan%20Name!OpenView&Start=2 (2 of 2)8/8/2006 6:50:44 PM Powerline Plans Plan Name Bin Number PCN Phone Number Acordia Sr Benefits Horizons 600428 00790015 800-522-7487 ACT Industries, Inc. -

Current Challenges to the Federal Judiciary Carolyn Dineen King

Louisiana Law Review Volume 66 | Number 3 Spring 2006 Current Challenges to the Federal Judiciary Carolyn Dineen King Repository Citation Carolyn Dineen King, Current Challenges to the Federal Judiciary, 66 La. L. Rev. (2006) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol66/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Current Challenges to the Federal Judiciary Carolyn Dineen King* -Remarks at the Judge Alvin B. and Janice Rubin 2005 Lectures, October 25, 2005, Paul M. Hebert Law Center, Louisiana State University. INTRODUCTION In the United States, an independent judicial system enjoying the confidence of the citizenry is central to preserving the rule of law. The rule of law, in turn, is the bedrock of both our federal and state judicial systems. I will mention several challenges to the independence of the Judiciary that are operative today and seem, to me at least, to be particularly troubling. I will also talk about some fundamental changes that are occurring in the federal district and appellate courts. During the nearly seven years that I have been Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit and a member of the Judicial Conference of the United States, I have been privileged to have a ring side seat on the relations among the three branches of government and particularly on the effects of the political branches on the federal judiciary. -

Challenges to Judicial Independence an a Perspective from the Circuit Co

HALLOWS | LECTURE Challenges to Judicial Independence an A Perspective from the Circuit Co The Honorable Carolyn Dineen King, of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, visited campus last year as the Law School’s Hallows Judicial Fellow. The highlight of her visit was the annual Hallows Lecture, which was subsequently published in the Marquette Law Review and appears here as well. Introduction by Dean Joseph D. Kearney t is my privilege to welcome you to our annual E. Harold Hallows Lecture. This lecture series began in 1995, Iand we have had the good fortune more or less annually since then to be joined by a distinguished jurist who spends a day or two within the Law School community. This is our Hallows Judicial Fellow. Some of these judges we meet for the fi rst time. Others are more known to us beforehand—already part of us, really. Within that latter category, I am very grateful that today we have with us two of our past Hallows Fellows. I would like to recognize them. Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson of the Wisconsin Supreme Court delivered the Hallows Lecture in 2003, my fi rst year as dean. She is a friend of the Law School as well as a friend of this year’s Hallows Fellow. The other is Judge Diane Sykes, a Marquette lawyer (Class of 1984), who is a member of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit and who delivered the Hallows Lecture in 2006. Thank you to both Chief Justice Abrahamson and Judge Sykes for being with us today. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 17-205 In the Supreme Court of the United States October Term, 2017 In re CARL BERNOFSKY, Petitoner DR. CARL BERNOFSKY, Petitioner, v. JUDICIAL COUNCIL OF THE UNITED STATES FIFTH CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS, Respondent. APPENDIX for Petition for Writ of Mandamus CARL BERNOFSKY 109 Southfield Road, Apt. 51H Shreveport, Louisiana 71105 (318) 869-3871 Petitioner, Pro Se TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Petition of Nov. 2, 2016, “Grounds for 1 Impeaching Helen “Ginger” Berrigan, Judge, Federal District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana.” Submitted to all members of the Judicial Council of the Fifth Circuit. 2. Cover letter of Nov. 2, 2016 from petitioner 61 Carl Bernofsky to Hon. Carl E. Stewart, for the petition: “Grounds for Impeaching Helen “Ginger” Berrigan, Judge, Federal District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana.” Similar letters, together with the petition, were submitted to all members of the Judicial Council of the Fifth Circuit. 3. Order, signed Dec. 28. 2016 by Chief Judge 63 Carl E. Stewart, “IN RE: The Complaint of Carl Bernofsky Against United States Senior District Judge Helen G. Berrigan, Eastern District of Louisiana, Under the Judicial Improvements Act of 2002.” Filed Jan. 4, 2017 as “Complaint Number: 05-17-90013.” i TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONT.) 4. Cover letter of Jan. 4, 2017 from Fifth 70 Circuit Deputy Clerk, Shelley E. Saltzman, to Carl Bernofsky, informing him of Judge Stewart’s dismissal of “Judicial Misconduct Complaint No. 05-17-90013.” 5. Petition to the Judicial Council of the Fifth 72 Circuit for review of Judicial Misconduct Complaint No. 05-17-90013, submitted Jan. -

Food Marketing Policy Issue Paper

Food Marketing Policy Issue Paper Food Marketing Policy Issue No. 31 November 2002 Papers address particular policy or marketing issues in a non-technical manner. They summarize research Supermarket Prices Need results and provide insights to Come Down for users outside the research community. Single copies are available at no charge. The last page lists all Food Policy Issue Papers to date, and describes other by publication series available from the Food Marketing Ronald W. Cotterill Policy Center. Tel (860) 486-1927 Fax (860) 486-2461 Food Marketing Policy Center email: [email protected] http://www.fmpc.uconn.edu University of Connecticut Food Marketing Policy Center, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Connecticut, 1376 Storrs Road, Unit 4021, Storrs, CT 06269-4021 ctnow.com: Supermarket Milk Prices Need To Come Down Page 1 of 2 http://www.ctnow.com/news/opinion/op_ed/hc-milk1126.artnov26.story Supermarket Milk Prices Need To Come Down Ronald W. Cotterill November 26 2002 I surveyed milk prices in 195 grocery stores in southern New England and neighboring areas of New York with four University of Connecticut graduate students two weeks ago. The average price for milk in Connecticut supermarkets was $3.05 per gallon. Yet dairy farmers are suffering because of the lowest prices for their product in 25 years - $1.06 per gallon in October. Adding insult to injury, retail and farm milk prices have been near these levels for a year. What we have is a virulent case of price gouging by supermarkets and, most likely, the dairy processors that supply them.