Papers on Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

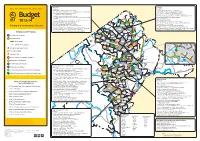

INVESTING in CANBERRA Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension to Moncrieff Group Centre ($24M)

AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Gungahlin Central Canberra New Works New Works Ÿ Environmental Offsets – Gungahlin (EPIC) ($0.462m). Ÿ Australia Forum – Investment ready ($1.5m). Ÿ Gungahlin Joint Emergency Services Centre – Future use study ($0.450m). Ÿ Canberra Theatre Centre Upgrades – Stage 2 ($1.850m). Ÿ Throsby – Access road and western intersection ($5.3m). Ÿ City Plan Implementation ($0.150m). BUDGET Ÿ William Slim/Barton Highway Roundabout Signalisation ($10.0m). Ÿ City to the Lake Arterial Roads Concept Design ($2.750m). Ÿ Corroboree Park – Ainslie Park Upgrade ($0.175m). TAYLOR JACKA Work in Progress Ÿ Dickson Group Centre Intersections – Upgrade ($3.380m). Ÿ Ÿ Disability Access Improvements – Reid CIT ($0.260m). 2014-15 Franklin – Community Recreation Irrigated Park Enhancement ($0.5m). BONNER Ÿ Gungahlin – The Valley Ponds and Stormwater Harvesting Scheme ($6.5m). Ÿ Emergency Services Agency Fairbairn – Incident management upgrades ($0.424m). MONCRIEFF Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension from Burrumarra Avenue to Mirrabei Drive ($11.5m). Ÿ Fyshwick Depot – Underground fuel storage tanks removal and site remediation ($1.5m). INVESTING IN CANBERRA Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension to Moncrieff Group Centre ($24m). Ÿ Lyneham Sports Precinct – Stage 4 tennis facility enhancement ($3m). Ÿ Horse Park Drive Water Quality Control Pond ($6m). Ÿ Majura Parkway to Majura Road – Link road construction ($9.856m). Ÿ Kenny – Floodways, Road Access and Basins (Design) ($0.5m). CASEY AMAROO FORDE Ÿ Narrabundah Ball Park Stage 2 – Design ($0.5m). HALL Ÿ Ÿ Throsby – Access Road (Design) ($1m). HALL New ACT Courts. INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS NGUNNAWAL Work in Progress Ÿ Ainslie Music Hub ($1.5m). Belconnen Ÿ Barry Drive – Bridge Strengthening on Commercial Routes ($0.957m). -

Architect Developer Designer KASPAREK ARCHITECTS PAVILION PROPERTY SERVICES DEPT

Imagine your new view. ARTIST IMPRESSION - MAY VARY In a world full of ordinary, Northshore delivers the extraordinary. Northshore has been carefully fashioned to deliver a higher standard of apartment living in the Kingston Foreshore. To the naked eye, the building is simple, elegant and truly modern. A closer inspection reveals a vastly complex and detailed design all of which come together to deliver a spectrum of beautiful apartments. Your perfect day as a Northshore resident... After years of development, The Kingston Foreshore has now arguably become the most sought after residential location in Canberra. It is home to some of not only Canberra’s, but Australia’s, most innovative and finest residential buildings The vision for the Foreshore precinct is coming to fruition, now offering a place where visitors and residents alike can holistically experience life, art and nature in balance. It truly delivers something for everyone. From chic cafés to trendy restaurants, residents can browse the Old Bus Depot Markets, enjoy the Canberra Glassworks and the heritage-listed Kingston Powerhouse, or simply stroll around the waters edge taking in the beautiful scenery. Enjoy a kayak on the lake or take advantage of the bike tracks with a ride or a jog. Or simply step outside your door to enjoy some of Canberra’s best dining establishments - all within walking distance. 7:30am 9:00am Wake up, open the blinds and take in your view Once you drop off your fresh produce from of the lake. Sit on your balcony and enjoy your the markets, it’s time for a walk or ride around breakfast before heading down the road to the lake. -

An Infrastructure Plan for the Act ISBN-13: 978 0 642 60465 1 ISBN-10: 0 642 60465 7

AN INFRASTRUCTURE PLAN FOR THE ACT ISBN-13: 978 0 642 60465 1 ISBN-10: 0 642 60465 7 © Australian Capital Territory, Canberra 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the Territory Records Office, Community and Infrastructure Services, Territory and Municipal Services, ACT Government, GPO Box 158, Canberra City ACT 2601. Produced by Publishing Services for the Chief Minister ’s Department Printed on recycled paper Publication No 08/1046 http://www.act.gov.au Telephone: Canberra Connect 132 281 ii Contents FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................................1 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................3 Infrastructure and economic growth .............................................................................................................................................4 An Infrastructure Plan for the ACT ....................................................................................................................................................4 2 THE ACT’S INFRASTRUCTURE LEGACY ..............................................................................................5 Excellent infrastructure befitting a national capital ...............................................................................................................6 -

Better Support for the Arts in Canberra

2 BETTER SUPPORT FOR THE ARTS IN CANBERRA The ACT Budget 2017-18 provides better support for Canberra’s thriving arts sector. The Budget invests in arts facilities right across our city, including the Ainslie Arts Centre, Gorman House Arts Centre, Strathnairn, Tuggeranong Arts Centre and Watson Arts Centre. The Government will also deliver on our commitment to invest in stage 2 of the Belconnen Arts Centre, with $15 million allocated to the project. This Budget will also deliver important funding for arts projects and arts events to provide greater certainty in arts project funding and support a vibrant calendar of events. We are ensuring that there will be $750,000 invested in arts projects. We are also ensuring that all Canberrans enjoy the investment the Government is making in the arts community by supporting a number of arts events in Canberra throughout the year, including Art, Not Apart, DESIGN Canberra and the Canberra Writers Festival. The Budget contains a $21.6 million package for the Arts over four years. Better arts facilities across the Territory The Budget is investing $16.3 million over four years into upgrading and expanding our arts centres and facilities across the city, including: • $15 million over three years for the expansion of Belconnen Arts Centre. This will fund the final design and construction of the stage two works. These upgrades will include a multi-use town hall/performance space, new dance studios and an expanded exhibition space; • $880,000 over four years in upgrades to five arts centres across the Territory – Ainslie Arts Centre, Gorman House Arts Centre, Strathnairn, Tuggeranong Arts Centre and Watson Arts Centre; • $280,000 to upgrade the Canberra Museum and Gallery (CMAG) with more secure, efficient and modern lighting; and • $100,000 for community consultation on upgrades to Canberra Theatre and performing arts infrastructure. -

Weston Park Conservation Management Plan

Weston Park Conservation Management Plan Report prepared for ACT Government Department of Territory and Municipal Services (TAMS) July 2011 Report Register The following report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Weston Park— Conservation Management Plan (CMP), undertaken by Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd in accordance with its quality management system. Godden Mackay Logan operates under a quality management system which has been certified as complying with the Australian/New Zealand Standard for quality management systems AS/NZS ISO 9001:2008. Job No. Issue No. Notes/Description Issue Date 09-6482 1 CMP Draft Report November 2010 09-6482 2 CMP Final Draft Report February 2011 09-6482 3 CMP Final Draft Report March 2011 09-6482 4 CMP Final Draft Report to ACT Heritage April 2011 09-6482 5 CMP Final Report July 2011 Copyright Historical sources and reference material used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced at the end of each section and/or in figure captions. Reasonable effort has been made to identify, contact, acknowledge and obtain permission to use material from the relevant copyright owners. Unless otherwise specified or agreed, copyright in this report vests in Godden Mackay Logan Pty Ltd (‘GML’) and in the owners of any pre-existing historic source or reference material. Moral Rights GML asserts its Moral Rights in this work, unless otherwise acknowledged, in accordance with the (Commonwealth) Copyright (Moral Rights) Amendment Act 2000. GML’s moral rights include the attribution of authorship, the right not to have the work falsely attributed and the right to integrity of authorship. -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Building and Tranforming Canberra

Belconnen Gungahlin AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY New Works New Works Ÿ $8m for University of Canberra Public Hospital (Design). Ÿ $7m for Horse Park Drive Water Quality Control Pond. Ÿ $3.9m for Continuity of Health Services Plan – Essential Infrastructure – Calvary Hospital. Ÿ $0.5m for Kenny – Floodways, Road Access and Basins (Design). Ÿ $2m for Belconnen High School Modernisation – Stage 1. Ÿ $0.3m for a New Camping Area at Exhibition Park in Canberra. Ÿ $1.3m for Calvary Hospital Car Park (Design). Ÿ $0.5m for Franklin – Community Recreation Irrigated Park Enhancement. Ÿ $0.951m for Belconnen and Tuggeranong Walk-In Centres. Ÿ $0.120m for Car Park Upgrade to Enhance Accessibility at Exhibition Park in Canberra. Ÿ $0.9m for Coppins Crossing Road and William Hovell Drive Intersection and Road Upgrades Continuing Works (2013-14 estimated expenditure) Budget JACKA (Feasibility). Ÿ Gungahlin Pool ($14.5m). Ÿ $0.350m for West Belconnen – Stormwater, Hydraulic and Utility Services (Feasibility). BONNER Ÿ Bonner Primary School ($12.5m). 2013-14 Ÿ $0.325m for West Belconnen – Roads and Traffic (Feasibility). Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension to Moncrieff Group Centre ($9.8m). Continuing Works (2013-14 estimated expenditure) Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension from Burrumarra Avenue to Mirrabei Drive ($7.7m). Ÿ Enhanced Community Health Centre – Belconnen ($20.2m). HALL CASEY AMAROO FORDE Ÿ Franklin Early Childhood School ($4m). HALL Building and transforming Canberra Ÿ ESA Station Upgrade and Relocation – Charnwood Station ($11.3m). NGUNNAWAL Ÿ Gungahlin Enclosed Oval – Construction of Grandstand ($3.5m). Ÿ West Macgregor Development – Macgregor Primary School Expansion ($3m). -

A National Capital, a Place to Live

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia a national capital, a place to live Inquiry into the Role of the National Capital Authority Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories July 2004 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2004 ISBN 0 642 78479 5 Cover – Marion and Walter Burley Griffin – Courtesy of the National Capital Authority Contents Foreword..................................................................................................................................................viii Membership of the Committee.................................................................................................................. x Terms of reference................................................................................................................................... xi List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................................xii List of recommendations........................................................................................................................ xiv 1 Introduction............................................................................................................. 1 Background.....................................................................................................................................2 The Griffin Legacy Project ............................................................................................................5 The Issues........................................................................................................................................6 -

(Canberra), Unemployment Relief Committee and Other Documents

The Great Depression in the FCT (Canberra), Unemployment Relief Committee and Other Documents Australian Archives A6270/1 E2/25/268 217 The Great Depression commenced in the Federal Capital Territory shortly after the opening of the Provisional Parliament House on 9th May, 1927. Reference to the threat of mass sackings is found in the report written in the June 1927 issue of the Canberra Community News by a representative of the White City Camp . The writer mentioned the rumour and how hard it was for men to Hump the Matilda in the winter months. By 1929 many men had lost their jobs. Some, particularly single men, left the territory in search of work. The unemployed who stayed had to ask for relief assistance and got behind in the rent. Two mess caterers who went broke at this time were Bill Mitchell of White City Camp and Mrs Stanley of Capitol Hill. On the next page is a letter written by Mrs Stanley in 1929 when she decided that she may save her business by turning it into a private boarding house. This measure failed and by the end of 1930 or early 1931 she was out of business. Bill Mitchell walked out of his business around the same time. Both she and Bill Mitchell provided meals for men who could not pay. Below: 1929 view from City Hill looking towards Capital Hill – On right is Albert Hall and left Westblock. Red Hill dominates the background. Photograph loaned by J Gibbs daughter of AE Gibbs, second Superintendent of Parks & Gardens. 218 219 In Canberra two camps were set up for unemployed men coming into the Territory in search of work -one for single men and the other for married.1 Single men were given a couple of weeks free accommodation and relief in the form of food packages before being moved on out of the territory. -

President's Annual Report – 2013-14

President’s Annual Report Christopher Watson (August 2014)– 2013-14 Your Committee Team Thanks to you all, especially our Secretary, John Connelly, for his meticulous minutes. Our treasurer, Doug Finlayson, not only keeps our finances in good shape, but also regularly writes a ‘Park Update’ with great pictures (these articles have also been printed in the magazines of the ACT National Parks Association and National Trust). The help of Vice President, Brian Rhynehart, and also Vena Murray, was much appreciated. Darryl Seto, our webmaster, ensures information goes far and wide! Darryl is also organising an art exhibition to be staged at the Belconnen Arts Centre in 2015. Our Patron, Dr Bryan Pratt, was ever willing to have a chat and give advice; we now look forward to advice from our new Co-Patron, Meredith Hunter. We’ve had deputations a-plenty, namely, ACT Assembly Members, Yvette Berry, Mary Porter, Mick Gentleman, Shane Rattenbury and Alistair Coe; also Federal Members, Andrew Leigh MHR, Senator Zed Seselja and Angus Taylor MHR. There have been continuing contacts and help, from the ACT National Trust, ACT National Parks Association, Ginninderra Catchment Group, Belconnen Community Council and the Conservation Council; also, frequent meetings with local landowner and developer, David Maxwell, who is the director of Riverview (Projects) Pty Ltd National Park Investigations As a result of our urging, the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service in 2013 assessed 274 ha in the area centred on Ginninderra Falls and near the Murrumbidgee River – Ginninderra Creek confluence. Their report, received by us in November 2013, acknowledged the area’s “conservation and recreational opportunities”, but unfortunately, said that it was “not a priority for purchase”. -

Mediaportal Report

Braidwood Times, Braidwood NSW 07 May 2014 General News, page 3 - 64.00 cm² Regional - circulation 707 (--W----) Copyright Agency licensed copy (www.copyright.com.au) ID 254997343 PAGE 1 of 1 back About Town LANDMARK 55th Annual Blue Ribbon Vealer & Calf Sale Friday 9th May FARMERS MARKET now on Saturday 10th May (due to Heritage day) and 31st May ( due to Book Fair) MOTHERS’ DAY Sunday 11 May FOLK MUSIC CLUB INC Thursday 15th May LANDMARK TRADE DAY Thursday 22nd May Once a year specials on rural merchandise and demonstrations of new products. NATIONAL WALK SAFE- LY TO SCHOOL DAY Friday 23 May 2014, www.walk.com.au WILDCARE TRAINING Basic Macropod course on 24th May. Become a member and learn to care for kangaroo joeys. Contact 0433 010 318 or [email protected]. au for further information and to register.” ANGLICAN BOOK FAIR June 6-9 long weekend, Interested in helping in any way? Call Marjorie 4846 1243 or Kerry 0407 907 118 LIKE US ON FACEBOOK Have you checked out the Braidwood Times online and on Facebook. See links to more regional and local stories and pictures. BT ONLINE With all that’s been going on locally check out the Braidwood Times online for the photo galleries. All the images are available for sale through the office for $12 per 4 sheet. Don Dorrigo Gazette, Don Dorrigo NSW 07 May 2014 General News, page 3 - 147.00 cm² Regional - circulation 1,000 (--W----) Copyright Agency licensed copy (www.copyright.com.au) ID 255329063 PAGE 1 of 1 back HERNANI PUBLIC SCHOOL Welcome back to a busy l term. -

Canberra Events

Summer 2018–19 Summer vibes Explore the outdoors, kick back with our summer of cricket and tick off cultural must-dos. VISITCANBERRA.COM.AU Love and Desire: Pre-Raphaelite Masterpieces from the Tate at the National Gallery of Australia. Image: John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott 1888 FOR THE CULTURE BUFFS… Enter a world of Love and Desire Across the Lake, immerse yourself as the Tate Britain loans exclusive in ancient times at the Rome: masterpieces from its unsurpassed City + Empire exhibition at the collection of Pre-Raphaelite National Museum of Australia. paintings to the National Gallery It’s exclusive to Canberra, with of Australia and experience a once artefacts from the British Museum. in a lifetime opportunity to see Delve into the life of the late Aussie these masterpieces in Australia. actor Heath Ledger: A Life in The Gallery will also be unveiling Pictures at the National Film and Spirits of the Pumpkins Sound Archive. For culture of another Descended into the Heavens 2015, kind, take in the roar of street an immersive installation of endless machines at the annual Summernats reflection, yellow pumpkins and black car festival (3–6 January). dots by cult contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama. Front cover: Fuel up with a sweet treat just like @wanderworkrepeat did at Space Kitchen. Left: Explore the Australian National Botanic Gardens this summer. Treat the family to a glamping experience these school holidays at Wildfest at Tidbinbilla. SOMETHING FOR THE KIDS… FOR THE LOVERS There’s plenty to keep the kids OF SPORT… amused these school holidays at our For a summer full of cricket, head national attractions and beyond.