Background Information Cinema Center (Block 21 Section 35, City)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

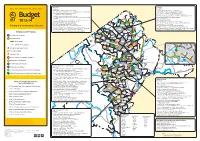

INVESTING in CANBERRA Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension to Moncrieff Group Centre ($24M)

AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Gungahlin Central Canberra New Works New Works Ÿ Environmental Offsets – Gungahlin (EPIC) ($0.462m). Ÿ Australia Forum – Investment ready ($1.5m). Ÿ Gungahlin Joint Emergency Services Centre – Future use study ($0.450m). Ÿ Canberra Theatre Centre Upgrades – Stage 2 ($1.850m). Ÿ Throsby – Access road and western intersection ($5.3m). Ÿ City Plan Implementation ($0.150m). BUDGET Ÿ William Slim/Barton Highway Roundabout Signalisation ($10.0m). Ÿ City to the Lake Arterial Roads Concept Design ($2.750m). Ÿ Corroboree Park – Ainslie Park Upgrade ($0.175m). TAYLOR JACKA Work in Progress Ÿ Dickson Group Centre Intersections – Upgrade ($3.380m). Ÿ Ÿ Disability Access Improvements – Reid CIT ($0.260m). 2014-15 Franklin – Community Recreation Irrigated Park Enhancement ($0.5m). BONNER Ÿ Gungahlin – The Valley Ponds and Stormwater Harvesting Scheme ($6.5m). Ÿ Emergency Services Agency Fairbairn – Incident management upgrades ($0.424m). MONCRIEFF Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension from Burrumarra Avenue to Mirrabei Drive ($11.5m). Ÿ Fyshwick Depot – Underground fuel storage tanks removal and site remediation ($1.5m). INVESTING IN CANBERRA Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension to Moncrieff Group Centre ($24m). Ÿ Lyneham Sports Precinct – Stage 4 tennis facility enhancement ($3m). Ÿ Horse Park Drive Water Quality Control Pond ($6m). Ÿ Majura Parkway to Majura Road – Link road construction ($9.856m). Ÿ Kenny – Floodways, Road Access and Basins (Design) ($0.5m). CASEY AMAROO FORDE Ÿ Narrabundah Ball Park Stage 2 – Design ($0.5m). HALL Ÿ Ÿ Throsby – Access Road (Design) ($1m). HALL New ACT Courts. INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS NGUNNAWAL Work in Progress Ÿ Ainslie Music Hub ($1.5m). Belconnen Ÿ Barry Drive – Bridge Strengthening on Commercial Routes ($0.957m). -

An Infrastructure Plan for the Act ISBN-13: 978 0 642 60465 1 ISBN-10: 0 642 60465 7

AN INFRASTRUCTURE PLAN FOR THE ACT ISBN-13: 978 0 642 60465 1 ISBN-10: 0 642 60465 7 © Australian Capital Territory, Canberra 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the Territory Records Office, Community and Infrastructure Services, Territory and Municipal Services, ACT Government, GPO Box 158, Canberra City ACT 2601. Produced by Publishing Services for the Chief Minister ’s Department Printed on recycled paper Publication No 08/1046 http://www.act.gov.au Telephone: Canberra Connect 132 281 ii Contents FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................................1 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................3 Infrastructure and economic growth .............................................................................................................................................4 An Infrastructure Plan for the ACT ....................................................................................................................................................4 2 THE ACT’S INFRASTRUCTURE LEGACY ..............................................................................................5 Excellent infrastructure befitting a national capital ...............................................................................................................6 -

Scientists' Houses in Canberra 1950–1970

EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 MILTON CAMERON Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cameron, Milton. Title: Experiments in modern living : scientists’ houses in Canberra, 1950 - 1970 / Milton Cameron. ISBN: 9781921862694 (pbk.) 9781921862700 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Scientists--Homes and haunts--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Architecture, Modern Architecture--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Canberra (A.C.T.)--Buildings, structures, etc Dewey Number: 720.99471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Sarah Evans. Front cover photograph of Fenner House by Ben Wrigley, 2012. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press; revised August 2012 Contents Acknowledgments . vii Illustrations . xi Abbreviations . xv Introduction: Domestic Voyeurism . 1 1. Age of the Masters: Establishing a scientific and intellectual community in Canberra, 1946–1968 . 7 2 . Paradigm Shift: Boyd and the Fenner House . 43 3 . Promoting the New Paradigm: Seidler and the Zwar House . 77 4 . Form Follows Formula: Grounds, Boyd and the Philip House . 101 5 . Where Science Meets Art: Bischoff and the Gascoigne House . 131 6 . The Origins of Form: Grounds, Bischoff and the Frankel House . 161 Afterword: Before and After Science . -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Building and Tranforming Canberra

Belconnen Gungahlin AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY New Works New Works Ÿ $8m for University of Canberra Public Hospital (Design). Ÿ $7m for Horse Park Drive Water Quality Control Pond. Ÿ $3.9m for Continuity of Health Services Plan – Essential Infrastructure – Calvary Hospital. Ÿ $0.5m for Kenny – Floodways, Road Access and Basins (Design). Ÿ $2m for Belconnen High School Modernisation – Stage 1. Ÿ $0.3m for a New Camping Area at Exhibition Park in Canberra. Ÿ $1.3m for Calvary Hospital Car Park (Design). Ÿ $0.5m for Franklin – Community Recreation Irrigated Park Enhancement. Ÿ $0.951m for Belconnen and Tuggeranong Walk-In Centres. Ÿ $0.120m for Car Park Upgrade to Enhance Accessibility at Exhibition Park in Canberra. Ÿ $0.9m for Coppins Crossing Road and William Hovell Drive Intersection and Road Upgrades Continuing Works (2013-14 estimated expenditure) Budget JACKA (Feasibility). Ÿ Gungahlin Pool ($14.5m). Ÿ $0.350m for West Belconnen – Stormwater, Hydraulic and Utility Services (Feasibility). BONNER Ÿ Bonner Primary School ($12.5m). 2013-14 Ÿ $0.325m for West Belconnen – Roads and Traffic (Feasibility). Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension to Moncrieff Group Centre ($9.8m). Continuing Works (2013-14 estimated expenditure) Ÿ Horse Park Drive Extension from Burrumarra Avenue to Mirrabei Drive ($7.7m). Ÿ Enhanced Community Health Centre – Belconnen ($20.2m). HALL CASEY AMAROO FORDE Ÿ Franklin Early Childhood School ($4m). HALL Building and transforming Canberra Ÿ ESA Station Upgrade and Relocation – Charnwood Station ($11.3m). NGUNNAWAL Ÿ Gungahlin Enclosed Oval – Construction of Grandstand ($3.5m). Ÿ West Macgregor Development – Macgregor Primary School Expansion ($3m). -

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria

SURVEY OF POST-WAR BUILT HERITAGE IN VICTORIA STAGE TWO: Assessment of Community & Administrative Facilities Funeral Parlours, Kindergartens, Exhibition Building, Masonic Centre, Municipal Libraries and Council Offices prepared for HERITAGE VICTORIA 31 May 2010 P O B o x 8 0 1 9 C r o y d o n 3 1 3 6 w w w . b u i l t h e r i t a g e . c o m . a u p h o n e 9 0 1 8 9 3 1 1 group CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Background 7 1.2 Project Methodology 8 1.3 Study Team 10 1.4 Acknowledgements 10 2.0 HISTORICAL & ARCHITECTURAL CONTEXTS 2.1 Funeral Parlours 11 2.2 Kindergartens 15 2.3 Municipal Libraries 19 2.4 Council Offices 22 3.0 INDIVIDUAL CITATIONS 001 Cemetery & Burial Sites 008 Morgue/Mortuary 27 002 Community Facilities 010 Childcare Facility 35 015 Exhibition Building 55 021 Masonic Hall 59 026 Library 63 769 Hall – Club/Social 83 008 Administration 164 Council Chambers 85 APPENDIX Biographical Data on Architects & Firms 131 S U R V E Y O F P O S T - W A R B U I L T H E R I T A G E I N V I C T O R I A : S T A G E T W O 3 4 S U R V E Y O F P O S T - W A R B U I L T H E R I T A G E I N V I C T O R I A : S T A G E T W O group EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this survey was to consider 27 places previously identified in the Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria, completed by Heritage Alliance in 2008, and to undertake further research, fieldwork and assessment to establish which of these places were worthy of inclusion on the Victorian Heritage Register. -

Canberra & District Historical Society Inc

Canberra & District Historical Society Inc. Founded 10 December 1953 PO Box 315, Curtin ACT 2605 ISSN 1839-4612 Edition No. 469 December 2018 Canberra History News – Edition No. 469 – December 2018 1 Canberra & District Historical Society Inc. Council President: Nick Swain Vice-Presidents: Esther Davies; Richard Reid Immediate Past President: Julia Ryan Hon. Treasurer: Julia Ryan Hon. Secretary: Vacant Councillors: Patricia Clarke, Tony Corp, Peter Dowling, Allen Mawer, Frances McGee, Marilyn Truscott, Ann Tündern-Smith, Kay Walsh Honorary Executive Officer: Helen Digan CDHS Canberra Historical Journal Editors: Kay Walsh and David Wardle (Published two times each year) CDHS Canberra History News Editors: Karen Moore, Sylvia Marchant and Ann Tündern-Smith (Published four times each year) Office Shopping Centre, Curtin ACT (Entrance from Strangways Street car park, opposite the service station) Postal Address Phone PO Box 315, Curtin ACT 2605 (02) 6281 2929 Email Website [email protected] www.canberrahistory.org.au Facebook page Canberra & District History https://www.facebook.com/groups/829568883839247/ Office Hours Tuesdays: 11.00 a.m. to 5.00 p.m. Most Wednesdays: 11.00 a.m. to 2.00 p.m. Most Saturdays: 10.00 a.m. to 12.00 noon Monthly Meetings Held from February to November on the 2nd Tuesday of each month Until further notice, in the Conference Room, just inside the entrance of ALIA House at 9-11 Napier Close, Deakin. Front Cover: Pat Wardle, foundation member and then President of the CDHS, demonstrates a possible use of a hipbath in Blundell’s Cottage. The cataloguer has noted, ‘A lovely illustration of her sense of humour’. -

Bricks Slates Logs Louvres to Gracefully Individually Unconsciously Conform

Bricks slates logs louvres to gracefully individually unconsciously conform. Poem by Taglietti to accompany an article on the Gibson House in the Australian Journal of Architecture and Arts, November 1965 Dr. Enrico Taglietti Paterson House Plans (1970), Aranda [www.enricotaglietti.com] Background Material www.architecture.com.au Craft ACT: Craft + Design Centre www.canberrahouse.com.au www.enricotaglietti.com Design Canberra 2018: Enrico Taglietti Photo: www.canberrahouse.com.au Photo: www.canberrahouse.com.au Photo: www.canberrahouse.com.au Photo: www.canberrahouse.com.au Photo: www.enricotaglietti.com Photo: www.enricotaglietti.com Patterson House (1970) Aranda I Downes Place (1965) Hughes I Sullivan House (1980) Wanniassa I Apolostic Nunciature (1975) Red Hill I Dickson Library (1968) I Giralang Primary School (1974) Craft ACT: Craft + Design Centre Design Canberra 2018: Enrico Taglietti Photo: www.enricotaglietti.com Photo: www.enricotaglietti.com Photo: MaxDupain Photo: Rachael Coghlan Photo: Rachael Coghlan Photo: Rachael Coghlan McKeown House (1965) Watson I Dingle House (1965) Sydney I Green House (1975) Garran I Australian War Memorial Annex (1978-79) Mitchell I Giralang Primary School (1975) Detail I Australian War Memorial Annex (1978-79) Mitchell Primary School (1974) Craft ACT: Craft + Design Centre Design Canberra 2018: Enrico Taglietti Enrico Taglietti Enrico Taglietti is recognised as an important architect and a leading practitioner of the late twentieth century organic style of architecture. His unique sculptural style draws upon Italian free form construction and post-war Japanese archi- tecture. He has designed many houses, schools, churches and commercial buildings in Canberra, Sydney and Mel- bourne and his projects have won numerous RAIA awards. -

R129 Mckeown House

Register of Significant Twentieth Century Architecture RSTCA No: R129 Name of Place: McKeown House Other/Former Names: Address/Location: 109 Irvine Street WATSON Block 30 Section 47 of Watson Listing Status: Registered Other Heritage Listings: Date of Listing: 2010 Level of Significance: National Citation Revision No: 0 Category: Residential Citation Revision Date: Style: Late Twentieth-Century Organic Date of Design: 1963 Designer: Enrico Taglietti Construction Period: 1963 - 1965 Client/Owner/Lessee: William & Robin McKeown Date of Addition: Design 1993 Construction 1995 Builder: Georg Teliczan (1965) STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE: The 1965 McKeown house at 109 Irvine Street, Watson is an exceptional creative achievement by Enrico Taglietti, having a sculptural form based on his new geometry for architecture, to create a work of art. The aesthetic quality of the house is remarkable, due to the elegant splayed angles of the white walls and jewel- like corner windows, under a sheltering flat roof with long horizontal timber fascias. The house is of architectural significance as a good example of the Late Twentieth-Century Organic style (1960-), as interpreted by Taglietti, which displays key indicators of the style – free asymmetrical massing, complex angular geometry complementing nature and clearly expressed timber structure. The splayed corner windows and the roof design, with rainwater falling to a central gutter and spilling out as a garden feature, were quite innovative. The high aesthetic quality of the 1995 addition matches that of the 1965 house. It has vertical massing which contrasts with the horizontal proportions of the earlier house, and the two buildings combine well visually. The 1995 addition is significant as a compact example of a more mature Taglietti design, in which the exterior massing reflects the internal arrangement of space to flow vertically as well as horizontally. -

Canberra Events

Summer 2018–19 Summer vibes Explore the outdoors, kick back with our summer of cricket and tick off cultural must-dos. VISITCANBERRA.COM.AU Love and Desire: Pre-Raphaelite Masterpieces from the Tate at the National Gallery of Australia. Image: John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott 1888 FOR THE CULTURE BUFFS… Enter a world of Love and Desire Across the Lake, immerse yourself as the Tate Britain loans exclusive in ancient times at the Rome: masterpieces from its unsurpassed City + Empire exhibition at the collection of Pre-Raphaelite National Museum of Australia. paintings to the National Gallery It’s exclusive to Canberra, with of Australia and experience a once artefacts from the British Museum. in a lifetime opportunity to see Delve into the life of the late Aussie these masterpieces in Australia. actor Heath Ledger: A Life in The Gallery will also be unveiling Pictures at the National Film and Spirits of the Pumpkins Sound Archive. For culture of another Descended into the Heavens 2015, kind, take in the roar of street an immersive installation of endless machines at the annual Summernats reflection, yellow pumpkins and black car festival (3–6 January). dots by cult contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama. Front cover: Fuel up with a sweet treat just like @wanderworkrepeat did at Space Kitchen. Left: Explore the Australian National Botanic Gardens this summer. Treat the family to a glamping experience these school holidays at Wildfest at Tidbinbilla. SOMETHING FOR THE KIDS… FOR THE LOVERS There’s plenty to keep the kids OF SPORT… amused these school holidays at our For a summer full of cricket, head national attractions and beyond. -

Apartments in the Heart of Canberra

Your companion on the road. We make your life stress-free by providing everything you need to create the stay you want. Apartment living with the benefits of a hotel service. stay real. Apartments in the heart of Canberra If you plan to stay one night, two nights or even a few weeks to a few months, Nesuto Canberra has a welcoming space for you to feel at home in. With the options of a Studio, 1 Bedroom or 2 Bedroom Apartment, you’ll feel comfortable coming back to our hotel at the end of each day to settle in for the night. All apartments have kitchens and are complete with a fully equipped laundry to make your stay as easy as possible. Nesuto. stay real. Celestion NESUTO CANBERRA & SURROUNDS 1 1. Canberra Bus Interchange 2 2. Canberra Centre 3 3. Civic Square 11 4 4. Australian War Memorial 5. Casino Canberra NESUTO CANBERRA 6. National Convention Centre 5 7. Canberra Olympic Pool and Health Club 8. Canberra Institute 6 of Technology 9. Commonwealth Park 7 8 10. Canberra and Region Visitors Centre 11. Canberra Theatre Centre 9 10 A WELCOMING LIVING SPACE Nesuto Canberra offers a variety of fully self-contained apartments, including Studio Apartments, One Bedroom Apartments, One Bedroom + Office Apartments and Two Bedroom Apartments perfect for either short or longer term stays. DINING Enjoy quality modern cuisine with family, friends or colleagues at the H2O on London Restaurant and Bar. Monday to Friday 7:00am-9:00pm Saturday 8:30am - 10:00am LOCAL DINING DELIGHTS DOBINSONS CAFE Mon-Thurs 6:30am to 5:30pm Fri 6:30am to 6:30pm Sat 7:30am to 5:30pm Sun 9:00am - 5:00pm COURGETTE RESTAURANT Open Mon - Sat Lunch 12:00am - 3:00pm Dinner 6:00pm - 11:00pm BANANA LEAF Open Mon - Sat Lunch 11:30am - 2:00pm Dinner 5:30pm - 9:00pm TEMPORADA Open Mon - Fri 7:30am - 10pm Sat 5:00pm - 10:00pm MARBLE AND GRAIN Open Mon - Fri 6:30am - 10:00pm Sat/Sun 7:00am - 10:00pm OUR FACILITIES Our central location and spacious apartments are complemented by an array of facilities at this apartment hotel. -

15 MAY 2019 Wednesday, 15 May 2019

NINTH ASSEMBLY 15 MAY 2019 www.hansard.act.gov.au Wednesday, 15 May 2019 Petitions: Restoration of Belconnen bus services—petition 12-19 .............................. 1659 Restoration of Belconnen bus services—petition 9-19 ................................ 1659 Canberra sexual health centre—petition 2-19 (Ministerial response) Motion to take note of petitions and response ......................................................... 1661 Leave of absence ...................................................................................................... 1662 Health—sexual health outreach ............................................................................... 1663 Health—hydrotherapy services ................................................................................ 1676 Questions without notice: ACTION bus service—weekend services .................................................... 1698 Visitors ..................................................................................................................... 1699 Questions without notice: Light rail—patronage ................................................................................... 1699 ACTION bus service—school services ........................................................ 1700 Federal election—impact .............................................................................. 1701 ACTION bus service—school services ........................................................ 1703 ACTION bus service—school services .......................................................