Complexity and Duality in the Hero of Wagner's "Ring"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Let Me Be Your Guide: 21St Century Choir Music in Flanders

Let me be your guide: 21st century choir music in Flanders Flanders has a rich tradition of choir music. But what about the 21st century? Meet the composers in this who's who. Alain De Ley Alain De Ley (° 1961) gained his first musical experience as a singer of the Antwerp Cathedral Choir, while he was still behind the school desks in the Sint-Jan Berchmans College in Antwerp. He got a taste for it and a few years later studied flute with Remy De Roeck and piano with Patrick De Hooghe, Freddy Van der Koelen, Hedwig Vanvaerenbergh and Urbain Boodts). In 1979 he continued his studies at the Royal Music Conservatory in Antwerp. Only later did he take private composition lessons with Alain Craens. Alain De Ley prefers to write music for choir and smaller ensembles. As the artistic director of the Flemish Radio Choir, he is familiar with the possibilities and limitations of a singing voice. Since 2003 Alain De Ley is composer in residence for Ensemble Polyfoon that premiered a great number of his compositions and recorded a CD dedicated to his music, conducted by Lieven Deroo He also received various commissions from choirs like Musa Horti and Amarylca, Kalliope and from the Flanders Festival. Alain De Ley’s music is mostly melodic, narrative, descriptive and reflective. Occasionally Alain De Ley combines the classical writing style with pop music. This is how the song Liquid Waltz was created in 2003 for choir, solo voice and pop group, sung by K’s Choice lead singer Sarah Bettens. He also regularly writes music for projects in which various art forms form a whole. -

Assenet Inlays Cycle Ring Wagner OE

OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 1 An Introduction to... OPERAEXPLAINED WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson 2 CDs 8.558184–85 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 2 An Introduction to... WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson CD 1 1 Introduction 1:11 2 The Stuff of Legends 6:29 3 Dark Power? 4:38 4 Revolution in Music 2:57 5 A New Kind of Song 6:45 6 The Role of the Orchestra 7:11 7 The Leitmotif 5:12 Das Rheingold 8 Prelude 4:29 9 Scene 1 4:43 10 Scene 2 6:20 11 Scene 3 4:09 12 Scene 4 8:42 2 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 3 Die Walküre 13 Background 0:58 14 Act I 10:54 15 Act II 4:48 TT 79:34 CD 2 1 Act II cont. 3:37 2 Act III 3:53 3 The Final Scene: Wotan and Brünnhilde 6:51 Siegfried 4 Act I 9:05 5 Act II 7:25 6 Act III 12:16 Götterdämmerung 7 Background 2:05 8 Prologue 8:04 9 Act I 5:39 10 Act II 4:58 11 Act III 4:27 12 The Final Scene: The End of Everything? 11:09 TT 79:35 3 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 4 Music taken from: Das Rheingold – 8.660170–71 Wotan ...............................................................Wolfgang Probst Froh...............................................................Bernhard Schneider Donner ....................................................................Motti Kastón Loge........................................................................Robert Künzli Fricka...............................................................Michaela -

05-09-2019 Siegfried Eve.Indd

Synopsis Act I Mythical times. In his cave in the forest, the dwarf Mime forges a sword for his foster son Siegfried. He hates Siegfried but hopes that the youth will kill the dragon Fafner, who guards the Nibelungs’ treasure, so that Mime can take the all-powerful ring from him. Siegfried arrives and smashes the new sword, raging at Mime’s incompetence. Having realized that he can’t be the dwarf’s son, as there is no physical resemblance between them, he demands to know who his parents were. For the first time, Mime tells Siegfried how he found his mother, Sieglinde, in the woods, who died giving birth to him. When he shows Siegfried the fragments of his father’s sword, Nothung, Siegfried orders Mime to repair it for him and storms out. As Mime sinks down in despair, a stranger enters. It is Wotan, lord of the gods, in human disguise as the Wanderer. He challenges the fearful Mime to a riddle competition, in which the loser forfeits his head. The Wanderer easily answers Mime’s three questions about the Nibelungs, the giants, and the gods. Mime, in turn, knows the answers to the traveler’s first two questions but gives up in terror when asked who will repair the sword Nothung. The Wanderer admonishes Mime for inquiring about faraway matters when he knows nothing about what closely concerns him. Then he departs, leaving the dwarf’s head to “him who knows no fear” and who will re-forge the magic blade. When Siegfried returns demanding his father’s sword, Mime tells him that he can’t repair it. -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

Bowen Abstract

The Rise and Fall of the Bass Clarinet in A Keith Bowen The bass clarinet in A was introduced by Wagner in Lohengrin in 1848. It was used up to 1990 in about sixty works by over twenty composers, including the Ring cycle, five Mahler symphonies and Rosenkavalier. But it last appeared in Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie (1948, revised 1990), and the instrument is generally regarded as obsolete.1 Several publications discuss the bass clarinet, notably Rice (2009). However, only Leeson2 and Joppig3 seriously discuss the ‘A’ instrument. Leeson suggests possibilities for its popularity: compatibility with the tonality of the soprano clarinets, the extra semitone at the bottom of the range and the sonority of the instrument. For its disappearance he posits the extension of range of the B¨ bass, and the convenience of having only one instrument. He suggests that its history is more likely to be found in the German than in the French bass clarinet tradition. Joppig examines one aspect of this tradition: Mahler’s use of the clarinet family. The first successful4 bass clarinet was the bassoon form, invented by Grenser in 1793 and made in quantity for almost a century. These instruments descended to at least C and had sufficient range for all parts for the bass clarinet in A.5 They were made in B¨ and C, but no examples in A are known so far. Their main use was in wind bands to provide a more powerful bass than the bassoon.6 For orchestral music, they were perceived to be only partially successful as bass for the clarinet family because of their different principle of construction.7 The modern form was invented by Desfontenelles in 1807 and improved by Buffet (1833) and Adolphe Sax (1838). -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

MISALLIANCE : Know-The-Show Guide

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey MISALLIANCE: Know-the-Show Guide Misalliance by George Bernard Shaw Know-the-Show Audience Guide researched and written by the Education Department of The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey Artwork: Scott McKowen The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey MISALLIANCE: Know-the-Show Guide In This Guide – MISALLIANCE: From the Director ............................................................................................. 2 – About George Bernard Shaw ..................................................................................................... 3 – MISALLIANCE: A Short Synopsis ............................................................................................... 4 – What is a Shavian Play? ............................................................................................................ 5 – Who’s Who in MISALLIANCE? .................................................................................................. 6 – Shaw on — .............................................................................................................................. 7 – Commentary and Criticism ....................................................................................................... 8 – In This Production .................................................................................................................... 9 – Explore Online ...................................................................................................................... 10 – Shaw: Selected -

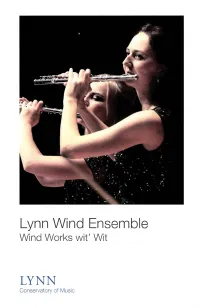

2015-2016 Lynn University Wind Ensemble-Wind Works Wit'wit

Lynn Wind Ensemble Wind Works wit' Wit LYNN Conservatory of Music Wind Ensemble Roster FLUTE T' anna Tercero Jared Harrison Hugo Valverde Villalobos Scott Kemsley Robert Williams Al la Sorokoletova TRUMPET OBOE Zachary Brown Paul Chinen Kevin Karabell Walker Harnden Mark Poljak Trevor Mansell Alexander Ramazanov John Weisberg Luke Schwalbach Natalie Smith CLARINET Tsukasa Cherkaoui TROMBONE Jacqueline Gillette Mariana Cisneros Cameron Hewes Halgrimur Hauksson Christine Pascual-Fernandez Zongxi Li Shaquille Southwell Em ily Nichols Isabel Thompson Amalie Wyrick-Flax EUPHONIUM Brian Logan BASSOON Ryan Ruark Sebastian Castellanos Michael Pittman TUBA Sodienye Fi nebone ALTO SAX Joseph Guimaraes Matthew Amedio Dannel Espinoza PERCUSSION Isaac Fernandez Hernandez TENOR SAX Tyler Flynt Kyle Mechmet Juanmanuel Lopez Bernadette Manalo BARITONE SAX Michael Sawzin DOUBLE BASS August Berger FRENCH HORN Mileidy Gonzalez PIANO Shaun Murray Al fonso Hernandez Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Lynn Wind Ensemble Kenneth Amis, music director and conductor 7:30 pm, Friday, January 15, 2016 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Onze Variations sur un theme de Haydn Jean Fran c;; aix lntroduzione - Thema (1912-1997) Variation 1: Pochissimo piu vivo Variation 2: Moderato Variation 3: Allegro Variation 4: Adagio Variation 5: Mouvement de va/se viennoise Variation 6: Andante Variation 7: Vivace Variation 8: Mouvement de valse Variation 9: Moderato Variation 10: Mo/to tranquil/a Variation 11 : Allegro giocoso Circus Polka Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Hommage a Stravinsky Ole Schmidt I. (1928-2010) II. Ill. Spiel, Op.39 Ernst Toch /. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Old Norse Mythology and the Ring of the Nibelung

Declaration in lieu of oath: I, Erik Schjeide born on: July 27, 1954 in: Santa Monica, California declare, that I produced this Master Thesis by myself and did not use any sources and resources other than the ones stated and that I did not have any other illegal help, that this Master Thesis has not been presented for examination at any other national or international institution in any shape or form, and that, if this Master Thesis has anything to do with my current employer, I have informed them and asked their permission. Arcata, California, June 15, 2008, Old Norse Mythology and The Ring of the Nibelung Master Thesis zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades “Master of Fine Arts (MFA) New Media” Universitätslehrgang “Master of Fine Arts in New Media” eingereicht am Department für Interaktive Medien und Bildungstechnologien Donau-Universität Krems von Erik Schjeide Krems, July 2008 Betreuer/Betreuerin: Carolyn Guertin Table of Contents I. Abstract 1 II. Introduction 3 III. Wagner’s sources 7 IV. Wagner’s background and The Ring 17 V. Das Rheingold: Mythological beginnings 25 VI. Die Walküre: Odin’s intervention in worldly affairs 34 VII. Siegfried: The hero’s journey 43 VIII. Götterdämmerung: Twilight of the gods 53 IX. Conclusion 65 X. Sources 67 Appendix I: The Psychic Life Cycle as described by Edward Edinger 68 Appendix II: Noteworthy Old Norse mythical deities 69 Appendix III: Noteworthy names in The Volsung Saga 70 Appendix IV: Summary of The Thidrek Saga 72 Old Norse Mythology and The Ring of the Nibelung I. Abstract As an MFA student in New Media, I am creating stop-motion animated short films. -

From Page to Stage: Wagner As Regisseur

Wagner Ia 5/27/09 3:55 PM Page 3 Copyrighted Material From Page to Stage: Wagner as Regisseur KATHERINE SYER Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to pro- duction matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flour- ished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage produc- tion in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increas- ingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production.