State–Church Relations in Iceland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icelandic Folklore

i ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE ii BORDERLINES approaches,Borderlines methodologies,welcomes monographs or theories and from edited the socialcollections sciences, that, health while studies, firmly androoted the in late antique, medieval, and early modern periods, are “edgy” and may introduce sciences. Typically, volumes are theoretically aware whilst introducing novel approaches to topics of key interest to scholars of the pre-modern past. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE ONLY iii ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE by ERIC SHANE BRYAN iv We have all forgotten our names. — G. K. Chesterton British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. © 2021, Arc Humanities Press, Leeds The author asserts their moral right to be identified as the author of this work. Permission to use brief excerpts from this work in scholarly and educational works is hereby granted provided that the source is acknowledged. Any use of material in this work that is an exception or limitation covered by Article 5 of the European Union’s Copyright Directive (2001/29/ EC) or would be determined to be “fair use” under Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act September 2010 Page 2 or that satisfies the conditions specified in Section 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act (17 USC §108, as revised by P.L. 94– 553) does not require the Publisher’s permission. FOR PRIVATE AND ISBN (HB): 9781641893756 ISBN (PB): 9781641894654 NON-COMMERCIAL eISBN (PDF): 9781641893763 USE ONLY www.arc- humanities.org Printed and bound in the UK (by CPI Group [UK] Ltd), USA (by Bookmasters), and elsewhere using print-on-demand technology. -

Pilgrims to Thule

MARBURG JOURNAL OF RELIGION, Vol. 22, No. 1 (2020) 1 Pilgrims to Thule: Religion and the Supernatural in Travel Literature about Iceland Matthias Egeler Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Abstract The depiction of religion, spirituality, and/or the ‘supernatural’ in travel writing, and more generally interconnections between religion and tourism, form a broad and growing field of research in the study of religions. This contribution presents the first study in this field that tackles tourism in and travel writing about Iceland. Using three contrasting pairs of German and English travelogues from the 1890s, the 1930s, and the 2010s, it illustrates a number of shared trends in the treatment of religion, religious history, and the supernatural in German and English travel writing about Iceland, as well as a shift that happened in recent decades, where the interests of travel writers seem to have undergone a marked change and Iceland appears to have turned from a land of ancient Northern mythology into a country ‘where people still believe in elves’. The article tentatively correlates this shift with a change in the Icelandic self-representation, highlights a number of questions arising from both this shift and its seeming correlation with Icelandic strategies of tourism marketing, and notes a number of perspectives in which Iceland can be a highly relevant topic for the research field of religion and tourism. Introduction England and Germany have long shared a deep fascination with Iceland. In spite of Iceland’s location far out in the North Atlantic and the comparative inaccessibility that this entailed, travellers wealthy enough to afford the long overseas passage started flocking to the country even in the first half of the nineteenth century. -

Early Religious Practice in Norse Greenland

Hugvísindasvið Early Religious Practice in Norse Greenland: th From the Period of Settlement to the 12 Century Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Andrew Umbrich September 2012 U m b r i c h | 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Early Religious Practice in Norse Greenland: th From the Period of Settlement to the 12 Century Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Andrew Umbrich Kt.: 130388-4269 Leiðbeinandi: Gísli Sigurðsson September 2012 U m b r i c h | 3 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Scholarly Works and Sources Used in This Study ...................................................... 8 1.2 Inherent Problems with This Study: Written Sources and Archaeology .................... 9 1.3 Origin of Greenland Settlers and Greenlandic Law .................................................. 10 2.0 Historiography ................................................................................................................. 12 2.1 Lesley Abrams’ Early Religious Practice in the Greenland Settlement.................... 12 2.2 Jonathan Grove’s The Place of Greenland in Medieval Icelandic Saga Narratives.. 14 2.3 Gísli Sigurðsson’s Greenland in the Sagas of Icelanders: What Did the Writers Know - And How Did They Know It? and The Medieval Icelandic Saga and Oral Tradition: A Discourse on Method....................................................................................... 15 2.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................................ -

Guð Blessi Ísland

Hugvísindasvið Guð blessi Ísland Þjóðríkistrú, þjóðkirkja og trúarhugmyndir Íslendinga Ritgerð til Cand.Theol. prófs Gunnar Stígur Reynisson Janúar 2012 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Kennimannleg guðfræði Guð blessi Ísland Þjóðríkistrú, þjóðkirkja og trúarhugmyndir Íslendinga Ritgerð til Cand.Theol.prófs Gunnar Stígur Reynisson Kt.: 271081-5109 Leiðbeinandi: Pétur Pétursson Janúar 2012 2 ...látum ekki hugfallast og styðjum hvert annað með ráðum og dáð. Á þann hátt, með íslenska bjartsýni, æðruleysi og samstöðu að vopni, munum við standa storminn af okkur. Guð blessi Ísland. -Geir H. Haarde, forsetisráðherra. 06. október 2008. 3 Efnisyfirlit Inngangur .................................................................................................................. 5 Trú og trúarbrögð ...................................................................................................... 6 Afhelgun ................................................................................................................ 9 Émilie Durkheim .................................................................................................. 11 Friedrich Schleiermacher .................................................................................... 12 Paul Tillich ........................................................................................................... 15 Tilurð þjóðríkistrúar ................................................................................................ 16 Jean-Jacques Rousseau ...................................................................................... -

World Council of Churches Financial Report 2016

World Council of Churches Financial Report 2016 1 World Council of Churches Financial Report 2016 World Council of Churches 150 Route de Ferney P.O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland Contents page Report to the Member Churches on the 2016 Financial Report 5 Report of the Statutory Auditor to the Executive Committee 9 and to the Member Churches Schedule I: Consolidated Balance Sheet 11 Schedule II: Consolidated Income & Expenditure Account 12 Schedule III: Consolidated Statement of Movements in Funds & Reserves 13 Schedule IV: Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 15 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 16 Schedule V: Restricted Funds 34 Schedule VI (a) and (b): Restricted Funds Programmes 35 Schedule VII: Unrestricted and Designated Funds 37 Schedule VIII: Unrestricted Operating Funds 38 Annual Summary of Contributions 39 Non-financial Contributions 49 Note on Membership Contributions 52 Financial Report 2016 5 REPORT TO MEMBER CHURCHES ON THE 2016 FINANCIAL REPORT We present with pleasure the financial report of the World Council of Churches for 2016, the third in the new cycle of work from 2014 to 2021. The 10th Assembly, Busan 2013, called the churches and ecumenical partners to join in a “pilgrimage of justice and peace.” In 2016, the Council moved forward with its strategy, working with churches and all people of goodwill in fostering new ways to further justice and peace. Financial results 2016 In 2016, the World Council of Churches reported total income of CHF 25 million, total expenditure of CHF 26.3 million and a resultant net decrease in funds and reserves of CHF 1.3 million. -

Icelandic Folklore

i ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE ii BORDERLINES approaches,Borderlines methodologies,welcomes monographs or theories and from edited the socialcollections sciences, that, health while studies, firmly androoted the in late antique, medieval, and early modern periods, are “edgy” and may introduce sciences. Typically, volumes are theoretically aware whilst introducing novel approaches to topics of key interest to scholars of the pre-modern past. iii ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE by ERIC SHANE BRYAN iv We have all forgotten our names. — G. K. Chesterton Commons licence CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. This work is licensed under Creative British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. © 2021, Arc Humanities Press, Leeds The author asserts their moral right to be identi�ied as the author of this work. Permission to use brief excerpts from this work in scholarly and educational works is hereby granted determinedprovided that to thebe “fair source use” is under acknowledged. Section 107 Any of theuse U.S.of material Copyright in Act this September work that 2010 is an Page exception 2 or that or limitation covered by Article 5 of the European Union’s Copyright Directive (2001/ 29/ EC) or would be 94– 553) does not require the Publisher’s permission. satis�ies the conditions speci�ied in Section 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act (17 USC §108, as revised by P.L. ISBN (HB): 9781641893756 ISBN (PB): 9781641894654 eISBN (PDF): 9781641893763 www.arc- humanities.org print-on-demand technology. -

Lífsins Ljós

##Ljosid-1-08 10.4.2008 11:50 Page 1 ##Ljosid-1-08 10.4.2008 11:50 Page 2 Guðrún Högnadóttir, formaður stjórnar Ljóssins. Lífsins ljós var búin innrétta í huganum hand- starfsmanna, frá gleði verka og til- verkstæði en við sáum fyrir okkur gangi iðju og með þátttöku ykkar. leigukostnaðinn. Það sem sumir litu Sagan af okkur félögunum í „hús- á sem skuldbindingu og framkvæmd inu“ í nóvember síðastliðinn minnir sáu aðrir sem jógasal og sauma- mig á mátt hugans, þá staðreynd að gallerí. ásetningur og sýn dregur okkur svo Það var hins vegar tær sann- miklu lengra en margt annað. Frelsi Guðrún Högnadóttir færingarkraftur og ótrúlega skýr sýn okkar til að velja okkar viðhorf er (og ómetanlegur stuðningur okkar nokkuð sem enginn getur rænt Ljósið iðar af lífi. Sú gleði og stemn- bakhjarla) sem auðveldaði okkur þá okkur. Hvorki fjárskortur né sjúk- ing sem ríkir í glæsilegu nýju ákvörðun um að flytja starfsemi dómur getur hrifsað frá okkur það húsnæði Ljóssins er engu lík. okkar í gamla Landsbankaútibúið. vald að kjósa okkar afstöðu. Við Hláturinn, sköpunarkrafturinn og Margar hendur unnu mikið verk og á getum alltaf valið með hvaða hætti vonin sem lýsir upp tilveruna á augnabliki varð húsið að ljósi í við lítum á hlutina, þó við stjórnum Landholtsveginum í dag er ansi langt myrkrinu. Opnunardagur Ljóssins í ekki öllu í lífinu. frá þeim gráa geim sem tók á móti vetur var sigur samvinnu og Það sem einn sér sem óyfirstígan- okkur einn napran haustdag fyrir stefnufestu, hátíð hjálpsemi og heil- lega hindrun sér annar sem stökk- hálfri eilífð síðan. -

November 6, 2014 Synod Mailing Letter Dear Sisters and Brothers In

November 6, 2014 Synod Mailing Letter Dear Sisters and Brothers in Christ – May grace and peace be yours in abundance (I Peter 1:2a). 2014 Conference Conventions This fall we gathered again in three conference conventions under the theme: Fed and Nourished, Filled and Refreshed, based on a portion of the hymn text, Baptized and Set Free. Together we explored, considered, dialoged and provided feedback to the “Study Guide on Word and Sacrament Ministry;” we worshipped ; and participated in necessary conference business and decision-making; including the election of rostered delegates to the 2015 National Convention. Two conferences also elected a new Dean: the West Central Conference elected Rev. Kathy Calkins (Peace, Innisfail) and the Southwest Conference elected Rev. Kristian Wold (Hope, Calgary). Thank you to Rev. John Lentz and Rev. Dennis Aicken for their years of service as Dean…and to their families and congregations…and to those continuing to serve as Dean: Rev. Markus Wilhelm, Rev. Eleanor Ness and Rev. Reg Berg. Much thanks to those congregations who hosted our conference conventions: Lakeland Lutheran, Cold Lake; Bethel and Messiah Lutheran, Camrose; and Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd, Lethbridge. Study Guide on Word and Sacrament Ministry In addition to our brief focus at the 2014 conference conventions I encourage individuals, congregations, cluster groups to study the Faith, Order and Doctrine (FOD) Committee of the National Church Council’s (NCC) study guide, “Study Guide on Word and Sacrament Ministry.” In the fall of 2012, the Faith, Order and Doctrine (FOD) Committee was asked by the National Church Council to consider the question of licensing lay people for sacramental ministry. -

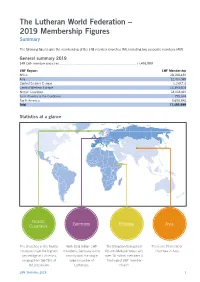

LWF 2019 Statistics

The Lutheran World Federation – 2019 Membership Figures Summary The following figures give the membership of the 148 member churches (M), including two associate members (AM). General summary 2019 148 LWF member churches ................................................................................. 77,493,989 LWF Regions LWF Membership Africa 28,106,430 Asia 12,4 07,0 69 Central Eastern Europe 1,153,711 Central Western Europe 13,393,603 Nordic Countries 18,018,410 Latin America & the Caribbean 755,924 North America 3,658,842 Total 77,493,989 Statistics at a glance Nordic Countries Germany Ethiopia Asia The churches in the Nordic With 10.8 million LWF The Ethiopian Evangelical There are 55 member countries have the highest members, Germany is the Church Mekane Yesus with churches in Asia. percentage of Lutherans, country with the single over 10 million members is ranging from 58-75% of largest number of the largest LWF member the population Lutherans. church. LWF Statistics 2019 1 2019 World Lutheran Membership Details (M) Member Church (AM) Associate Member Church (R) Recognized Church, Congregation or Recognized Council Church Individual Churches National Total Africa Angola ............................................................................................................................................. 49’500 Evangelical Lutheran Church of Angola (M) .................................................................. 49,500 Botswana ..........................................................................................................................................26’023 -

The Icelandic Federalist Papers

The Icelandic Federalist Papers No. 8: Other Defects of the Present Constitution (continued) To the People of Iceland: In addition to the possible defects, namely the environmental rights previously enumerated, that appear to be in the present constitution, there are others of no less importance that need to be discussed, specifically, the restrictions on religious freedom caused by the establishment of an official state religion. A constitution both frames and reflects the political consciousness in a society. The exercise of political freedom coincides with a constitution;1 constitutional regimes are constantly assimi- lated to virtuous forms of power. Yet it does not mean that the situation might not be improved and that things have to remain stable and inflexible. On the contrary, either a constitution is vague enough so that it is possible to comprehend things from a different contemporary perspec- tive whenever it is required, or it might be amended. Amending only permits some minor chang- es when the wording is already precise. The English philosophers Thomas Hobbes and John Locke in the 17th century and the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century defined a constitution as a social contract between the government and the people of a country. They laid down the solid foundations of modern constitutionalism. This contract involves retain- ing certain natural rights. Among these rights, today, an essential one is freedom of religion. Freedom of religion is developed in Articles 62, 63, and 64 of the present charter. In the case of the present constitution, it enables an amendment by law enacted by Althingi as far as freedom of conscience is concerned that is not embodied by a state-church separation. -

Apostolic Succession in the Porvoo Common Statement Unity Through a Deeper Sense of Apostolicity

Apostolic Succession in the Porvoo Common Statement Unity through a deeper sense of apostolicity Erik Eckerdal Uppsala University Thesis 2017-08-01 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Ihre-salen, Engelska parken, Uppsala, Friday, 22 September 2017 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Theology). The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Susan K Wood (Marquette University). Abstract Eckerdal, E. 2017. Apostolic Succession in the Porvoo Common Statement. Unity through a deeper sense of apostolicity. 512 pp. Uppsala: Department of Theology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2829-6. A number of ecumenical dialogues have identified apostolic succession as one of the most crucial issues on which the churches need to find a joint understanding in order to achieve the unity of the Church. When the Porvoo Common Statement (PCS) was published in 1993, it was regarded by some as an ecumenical breakthrough, because it claimed to have established visible and corporate unity between the Lutheran and Anglican churches of the Nordic-Baltic-British-Irish region through a joint understanding of ecclesiology and apostolic succession. The consensus has been achieved, according to the PCS, through a ‘deeper understanding’ that embraces the churches’ earlier diverse interpretations. In the international debate about the PCS, the claim of a ‘deeper understanding’ as a solution to earlier contradictory interpretations has been both praised and criticised, and has been seen as both possible and impossible. This thesis investigates how and why the PCS has been interpreted differently in various contexts, and discerns the arguments used for or against the ecclesiology presented in the PCS. -

Country Backgroun Report Iceland

Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools Country Background Report Iceland Ministry of Education, Science and Culture December 2014 The OECD and the European Commission (EC) have established a partnership for the Project, whereby participation costs of countries that are part of the European Union’s Erasmus+ program are partly covered. The participation of Iceland was organized with the support of the EC in the context of this partnership. Disclaimer: This report was prepared by the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Iceland, as an input to the OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools (School Resources Review). The document was prepared in response to guidelines the OECD provided to all countries. The opinions expressed are not those of the OECD or its Member countries. Further information about the OECD Review is available at www.oecd.org/edu/school/schoolresourcesreview.htm. Iceland Country Background Report 2 Table of contents List of tables and charts ...................................................................................................................... 4 List of abbreviations and glossary of terms ...................................................................................... 6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Executive summary ............................................................................................................................