The Dilemma Between Democratic Control Versus Military Reforms: the Case of the AFP Modernisation Program, 1991-2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

Civilian Control Over the Military in East Asia

Civilian Control over the Military in East Asia Aurel Croissant Ruprecht-Karls-Universität, Heidelberg September 2011 EAI Fellows Program Working Paper Series No. 31 Knowledge-Net for a Better World The East Asia Institute(EAI) is a nonprofit and independent research organization in Korea, founded in May 2002. The EAI strives to transform East Asia into a society of nations based on liberal democracy, market economy, open society, and peace. The EAI takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors. is a registered trademark. © Copyright 2011 EAI This electronic publication of EAI intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Copies may not be duplicated for commercial purposes. Unauthorized posting of EAI documents to a non-EAI website is prohibited. EAI documents are protected under copyright law. The East Asia Institute 909 Sampoong B/D, 310-68 Euljiro 4-ga Jung-gu, Seoul 100-786 Republic of Korea Tel. 82 2 2277 1683 Fax 82 2 2277 1684 EAI Fellows Program Working Paper No. 31 Civilian Control over the Military in East Asia1 Aurel Croissant Ruprecht-Karls-Universität, Heidelberg September 2011 Abstract In recent decades, several nations in East Asia have transitioned from authoritarian rule to democracy. The emerging democracies in the region, however, do not converge on a single pattern of civil-military relations as the analysis of failed institutionalization of civilian control in Thailand, the prolonged crisis of civil– military relations in the Philippines, the conditional subordination of the military under civilian authority in Indonesia and the emergence of civilian supremacy in South Korea in this article demonstrates. -

PR Move to Attract More Capital and Investment

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Djokovic wins US Open, equals QSE off ers German Sampras’ fi rms new promising opportunities mark published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 10938 September 11, 2018 Moharram 1, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Qatar, US review ties PR move to Our Say attract more capital and By Faisal Abdulhameed al-Mudahka Editor-in-Chief investment O Cardholders will enjoy health, The root of His Highness the Deputy Amir Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad al-Thani met at his off ice at the Amiri Diwan yesterday with the President of US Chamber of Commerce Thomas Donohue and US businessmen delegation, who called on the Deputy Amir education benefits to greet him on their visit to the country. During the meeting, they reviewed the strong relations between Qatar and the US terrorism and discussed ways to boost and develop them in various fields especially economic partnership and trade exchange, in he initiative to grant permanent and investment purposes in accord- light of the Qatar-US Business Council. They also exchanged views on future joint projects which will benefit both countries residency to non-Qatari indi- ance with stipulations. and their people. Tviduals will help increase invest- The cardholder may leave the coun- still exists ments and attract more capital, con- try and return to it during the period of tributing to further economic growth its validity without obtaining any con- In a a series of co-ordinated at- in the country, while the State can also sent or permit. -

Policy Briefing

Policy Briefing Asia Briefing N°83 Jakarta/Brussels, 23 October 2008 The Philippines: The Collapse of Peace in Mindanao Once the injunction was granted, the president and her I. OVERVIEW advisers announced the dissolution of the government negotiating team and stated they would not sign the On 14 October 2008 the Supreme Court of the Philip- MOA in any form. Instead they would consult directly pines declared a draft agreement between the Moro with affected communities and implied they would Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Philippines only resume negotiations if the MILF first disarmed. government unconstitutional, effectively ending any hope of peacefully resolving the 30-year conflict in In the past when talks broke down, as they did many Mindanao while President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo times, negotiations always picked up from where they remains in office. The Memorandum of Agreement on left off, in part because the subjects being discussed Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD or MOA), the culmination were not particularly controversial or critical details of eleven years’ negotiation, was originally scheduled were not spelled out. This time the collapse, followed to have been signed in Kuala Lumpur on 5 August. At by a scathing Supreme Court ruling calling the MOA the last minute, in response to petitions from local offi- the product of a capricious and despotic process, will cials who said they had not been consulted about the be much harder to reverse. contents, the court issued a temporary restraining order, preventing the signing. That injunction in turn led to While the army pursues military operations against renewed fighting that by mid-October had displaced three “renegade” MILF commanders – Ameril Umbra some 390,000. -

Qatar Deploys Hi-Tech Vessels for Maritime Safety, Security

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 US fi rms see Qatar as gateway A dazzling decade of to Gulf and Mideast region Asian men’s football published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXX No. 11413 December 31, 2019 Jumada I 5, 1441 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals In brief QATAR | Offi cial Qatar deploys Amir sends message to Austrian president His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani sent yesterday hi-tech vessels a written message to Austrian President Alexander Van der Bellen, pertaining to bilateral ties and means to bolster them. Qatar’s ambassador to Austria and Permanent for maritime Representative to the UN and International Organisations in Vienna, Sultan bin Salmeen al-Mansouri, delivered the message yesterday during a meeting with Austrian safety, security President’s Adviser for International Aff airs Bettina Kirnbauer. atar has launched a vessel to following up on the navigational aid ARAB WORLD | Crisis monitoring project, which system and detecting any marine pol- Iraq warns US ties at Qseeks not only to enhance mar- lution and reporting it to the bodies stake aft er strikes itime security but also preserve marine concerned. environment. The monitoring vessels, to be de- Iraq’s government warned yesterday The project, launched from the ployed on Qatari waters and ports, that its relations with the United Pearl-Qatar, comes within the frame- would support the security and safety States were at risk after deadly work of the Ministry of Transport and of maritime navigation and the protec- American air strikes against a pro- Communication’s (MoTC) eff ort to de- tion of marine environment. -

Special Issue

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

Chapter 2 Agribusiness Situationer ------23 Goals, Strategies and Action Plans ------28

Medium-Term Philippine Development Plan 2004-2010 Philippine Copyright @ 2004 by the National Economic and Development Authority Printed in Manila, Philippines ISSN 0119-3880 Contents Foreword ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ vii Preface -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ix List of Tables ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- xii List of Figures ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ xv Introduction I. The Basic Tasks -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 II. The Macroeconomy ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 PART I Economic Growth and Job Creation Chapter 1 Trade and Investment Situationer -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 Goals, Strategies and Action Plans ---------------------------------------------------- 12 Chapter 2 Agribusiness Situationer -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 23 Goals, Strategies and Action Plans ---------------------------------------------------- 28 Chapter 3 Environment and Natural Resources Situationer -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 43 Goals, Strategies and Action Plans ---------------------------------------------------- 48 Chapter 4 Housing Construction Situationer -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Protracted People's War in the Philippines a Persistent Communist Insurgency

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2007-03 Protracted people's war in the Philippines a persistent communist insurgency Osleson, Jason T. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3623 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS PROTRACTED PEOPLE’S WAR IN THE PHILIPPINES: A PERSISTENT COMMUNIST INSURGENCY by Jason T. Osleson March 2007 Thesis Advisor: Michael Malley Second Reader: Letitia Lawson Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED March 2007 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Protracted People’s War in the Philippines: A 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Persistent Communist Insurgency 6. AUTHOR(S) Jason T. Osleson 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Download the Case Study Report on Prevention in the Philippines Here

International Center for Transitional Justice Disrupting Cycles of Discontent TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND PREVENTION IN THE PHILIPPINES June 2021 Cover Image: Relatives and friends hold balloons during the funeral of three-year-old Kateleen Myca Ulpina on July 9, 2019, in Rodriguez, Rizal province, Philippines. Ul- pina was shot dead by police officers conducting a drug raid targeting her father. (Ezra Acayan/Getty Images) Disrupting Cycles of Discontent TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND PREVENTION IN THE PHILIPPINES Robert Francis B. Garcia JUNE 2021 International Center Disrupting Cycles of Discontent for Transitional Justice About the Research Project This publication is part of an ICTJ comparative research project examining the contributions of tran- sitional justice to prevention. The project includes country case studies on Colombia, Morocco, Peru, the Philippines, and Sierra Leone, as well as a summary report. All six publications are available on ICTJ’s website. About the Author Robert Francis B. Garcia is the founding chairperson of the human rights organization Peace Advocates for Truth, Healing, and Justice (PATH). He currently serves as a transitional justice consultant for the Philippines’ Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and manages Weaving Women’s Narratives, a research and memorialization project based at the Ateneo de Manila University. Bobby is author of the award-winning memoir To Suffer thy Comrades: How the Revolution Decimated its Own, which chronicles his experiences as a torture survivor. Acknowledgments It would be impossible to enumerate everyone who has directly or indirectly contributed to this study. Many are bound to be overlooked. That said, the author would like to mention a few names represent- ing various groups whose input has been invaluable to the completion of this work. -

Decisions Adopted by the IPU Governing Council at Its 204Th

140th IPU Assembly Doha (Qatar), 6–10 April 2019 Governing Council CL/204/9(b)-R.2 Item 9(b) 10 April 2019 Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians Decisions adopted by the IPU Governing Council at its th 204 session (Doha, 10 April 2019) CONTENTS Page Africa • Côte d’Ivoire: Mr. Alain Lobognon and Mr. Jacques Ehouo Decision ....................................................................................... 1 • Democratic Republic of Congo: Mr. Pierre Jacques Chalupa Decision ....................................................................................... 4 • Democratic Republic of Congo: Mr. Eugène Diomi Ngongala Decision ........................................................................................ 6 • Democratic Republic of Congo: Mr. Franck Diongo Decision ........................................................................................ 8 Americas • Ecuador: Mr. José Cléver Jimenez Carbera Decision ........................................................................................ 10 • Venezuela: Sixty-four parliamentarians Decision ........................................................................................ 12 Asia • Maldives: Seven parliamentarians Decision ........................................................................................ 17 • Mongolia: Mr. Zorig Sanjasuuren Decision ........................................................................................ 20 • Philippines: Four parliamentarians Decision ....................................................................................... -

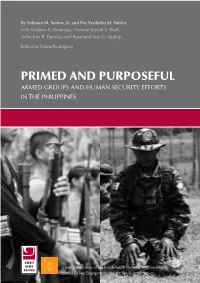

Primed and Purposeful

South-South Network for Non-State Armed Group Engagement By Soliman M. Santos, Jr. and Paz Verdades M. Santos 18 Mariposa St., Cubao, 1109 Quezon City, Philippines with Octavio A. Dinampo, Herman Joseph S. Kraft, PURPOSEFUL PRIMED AND p +632 7252153 Artha Kira R. Paredes, and Raymund Jose G. Quilop e [email protected] Edited by Diana Rodriguez w www.southsouthnetwork.com Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland PRIMED AND PURPOSEFUL p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 ARMED GROUPS AND HUMAN SECURITY EFFORTS e [email protected] IN THE PHILIPPINES w www.smallarmssurvey.org Soliman M. Santos, Jr. and Paz Verdades M. Santos and Paz Verdades Soliman M. Santos, Jr. Primed and Purposeful: Armed Groups and Human Security Efforts in the Philippines pro- vides the political and historical detail necessary to understand the motivations and probable outcomes of conflicts in the country. The volume explores related human security issues, including the willingness of several Filipino armed groups to negotiate political settlements to the conflicts, and to contemplate the demobilization and reintegration of combatants into civilian life. Light is also shed on the use of small arms—the weapons of choice for armed groups—whose availability is maintained through leakage from government arsenals, porous borders, a thriving domestic craft industry, and a lax regulatory regime. —David Petrasek, Author, Ends and Means: Human Rights Approaches to Armed Groups (International Council on Human Rights Policy, 2000) At the centre of this book are the ‘primed and purposeful’ protagonists of the Philippines’ two major internal armed conflicts: the nationwide Communist insurgency and the Moro insurgency in the Muslim part of Mindanao. -

UNDERTOW in the THIRD WAVE: UNDERSTANDING the REVERSION from DEMOCRACY by PETER ALLYN FERGUSON a THESIS SUBMITTED in PARTIAL

UNDERTOW IN THE THIRD WAVE: UNDERSTANDING THE REVERSION FROM DEMOCRACY by PETER ALLYN FERGUSON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Political Science) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2009 © Peter Allyn Ferguson Abstract In 2007, the world suffered a net decline in freedom for the second successive year for the first time in fifteen years. There are indications of global democratic stagnation. Coups and democratic reversions continue to occur. Why do regimes sometimes experience reversions away from democracy? An analysis of data from 1972-2003 indicates that for every $1 increase in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, the odds of a democratic reversion decrease 0.2%; for each 1% increase in GDP growth, the odds of a democratic reversal decrease 9.2%; and, for each 1 unit increase in Consumer Price Index (CPI), there is a 4.1% increase in the likelihood of democratic reversion. When the analysis is limited strictly to a comparison of democratic reversion cases and ongoing democratic regimes, variables addressing political institutional configurations, vulnerabilities to international pressures and civilian control over the military are either insignificant or provide very little purchase for explaining variance on the dependent variable. The dissertation includes thirty case studies of reversions from democracy, representing one universe of such cases from 1975-2003. Based on an analysis of these cases, several conclusions may be drawn. On economic issues, the case studies indicate we should be cautious in overstating the importance of economic performance and they draw attention to the problematic nature of analyses based on one year lags.