Etherotopia, an Ideal State and a State of Mind : Utopian Philosophy As Literature and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illuminating the Darkness: the Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2013 Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art Cameron Dodworth University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Dodworth, Cameron, "Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel and Visual Art" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 79. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART by Cameron Dodworth A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Nineteenth-Century Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Laura M. White Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2013 ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART Cameron Dodworth, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Laura White The British Gothic novel reached a level of very high popularity in the literary market of the late 1700s and the first two decades of the 1800s, but after that point in time the popularity of these types of publications dipped significantly. -

Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2008-03-28 Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R. Clark Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Clark, Bradley R., "Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1350. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1350 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Using the ZMET Method 1 Running head: USING THE ZMET METHOD TO UNDERSTAND MEANINGS Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R Clark A project submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Brigham Young University April 2008 Using the ZMET Method 2 Copyright © 2008 Bradley R Clark All Rights Reserved Using the ZMET Method 3 Using the ZMET Method 4 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a project submitted by Bradley R Clark This project has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. -

Lioi, Anthony. "The Great Music: Restoration As Counter-Apocalypse in the Tolkien Legendarium." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "The Great Music: Restoration as Counter-Apocalypse in the Tolkien Legendarium." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 123–144. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 12:12 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 The Great Music: Restoration as Counter-Apocalypse in the Tolkien Legendarium In which I assert that J. R. R. Tolkien’s legendarium begins with an enchanted sky, which provides the narrative framework for a restoration ecology based on human alliance with other creatures. This alliance protects local and planetary environments from being treated like garbage. Tolkien’s restorative framework begins in the Silmarillion with “The Music of the Ainur,” a cosmogony that details the creation of the universe by Powers of the One figured as singers and players in a great music that becomes the cosmos. This is neither an organic model of the world as body nor a technical model of the world as machine, but the world as performance and enchantment, coming- into-being as an aesthetic phenomenon. What the hobbits call “magic” in the Lord of the Rings is enchantment, understood as participation in the music of continuous creation. In his essay “On Fairy-Stories,” Tolkien theorized literary enchantment as the creation of a “Secondary World” of art that others could inhabit. -

Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2017 To Start, Continue, and Conclude: Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing Gabriel E. Romaguera University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Romaguera, Gabriel E., "To Start, Continue, and Conclude: Foregrounding Narrative Production in Serial Fiction Publishing" (2017). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 619. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/619 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO START, CONTINUE, AND CONCLUDE: FOREGROUNDING NARRATIVE PRODUCTION IN SERIAL FICTION PUBLISHING BY GABRIEL E. ROMAGUERA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF Gabriel E. Romaguera APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Valerie Karno Carolyn Betensky Ian Reyes Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2017 Abstract This dissertation explores the author-text-reader relationship throughout the publication of works of serial fiction in different media. Following Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of authorial autonomy within the fields of cultural production, I trace the outside influence that nonauthorial agents infuse into the narrative production of the serialized. To further delve into the economic factors and media standards that encompass serial publishing, I incorporate David Hesmondhalgh’s study of market forces, originally used to supplement Bourdieu’s analysis of fields. -

A Bit of Lit: Packet 1

A Bit of Lit: Packet 1 - Tossups Written by Devin Humphreys Input from Harris Bunker, Wendy Erickson, Will Nediger, and Angela Reid Originally Read at PACE NSC, 4 June 2016 TOSSUP 1. This author wrote an extended essay in which she states that women must be lifted out of poverty in order to write good fiction. In a different novel by this author, a character commits suicide after being involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric institution; the title character hears of the suicide of that character, (*) Septimus Smith, at a party she was hosting. In that work by this author, Richard is the “simple” husband of the title character, who is a London high society lady. This author’s affair with Vita Sackville-West inspired one work by this author that is both a love letter and a satire; that work is Orlando. For 10 points, name this author of Mrs. Dalloway. ANSWER: Virginia Woolf TOSSUP 2. In one novel by this author, two characters get into a duel against two carpetbaggers on Election Day. One of those characters, Drusilla, disappears towards the end of the novel she appears in, but not before giving another character two pistols to defend the family honor against Ben Redmond. That novel is the prequel to another work by this author, in which (*) Bayard becomes a reckless driver and marries Narcissa Benbow. In another work, this author of The Unvanquished and Sartoris also wrote about the thirty-year fall of the Compson family. For 10 points, name this author of The Sound and the Fury. -

Bowl Round 4

USABB Regionals 2015-2016 Round 4 Round 4 First Half (1) These particles are the lightest charged leptons, and have a half integer spin. Two of these particles cannot exist in the same orbital with the same spin, according to the (*) Pauli Exclusion Principle. Atoms that have more or fewer of these particles than of protons have charge, and are called ions. For ten points, name these negatively charged subatomic particles that travel around the nucleus. ANSWER: electrons (1) This retrovirus infects and kills T cells, weakening the body's immune response. For ten points each, Name this virus that can lead to acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS. ANSWER: HIV (or human immunodeficiency virus) The HIV virus can easily spread through this process of receiving blood intravenously, though screening has made the rate of such accidental infections exceptionally low in developed countries. ANSWER: blood transfusion When HIV infects cells, it copies its RNA genome into the DNA of the host cell, the reverse direction of this genetic process in which DNA is copied into RNA. ANSWER: transcription (accept reverse transcription) (2) This character chides Kitty, Dinah's kitten, by holding it up to a mirror, and she liberates the pig-like child of the Duchess. This girl uses a flamingo to play croquet with the Queen of Hearts. She learns poetry from (*) Tweedle-Dee and Tweedle-Dum, and follows the mysterious Cheshire Cat. For ten points, name this girl, who has Adventures in Wonderland in a pair of books by Lewis Carroll. ANSWER: Alice Liddell Page 1 USABB Regionals 2015-2016 Round 4 (2) One of the protagonists of this novel steals an item from Gollum, who refers to that item as \precious." For ten points each, Name this fantasy novel about Frodo and Sam's journey from the Shire with Aragorn and Gandalf to defeat Sauron in Mordor. -

Disability, Literature, Genre: Representation and Affect in Contemporary Fiction REPRESENTATIONS: H E a LT H , DI SA BI L I T Y, CULTURE and SOCIETY

Disability, Literature, Genre: Representation and Affect in Contemporary Fiction REPRESENTATIONS: H E A LT H , DI SA BI L I T Y, CULTURE AND SOCIETY Series Editor Stuart Murray, University of Leeds Robert McRuer, George Washington University This series provides a ground-breaking and innovative selection of titles that showcase the newest interdisciplinary research on the cultural representations of health and disability in the contemporary social world. Bringing together both subjects and working methods from literary studies, film and cultural studies, medicine and sociology, ‘Representations’ is scholarly and accessible, addressed to researchers across a number of academic disciplines, and prac- titioners and members of the public with interests in issues of public health. The key term in the series will be representations. Public interest in ques- tions of health and disability has never been stronger, and as a consequence cultural forms across a range of media currently produce a never-ending stream of narratives and images that both reflect this interest and generate its forms. The crucial value of the series is that it brings the skilled study of cultural narratives and images to bear on such contemporary medical concerns. It offers and responds to new research paradigms that advance understanding at a scholarly level of the interaction between medicine, culture and society; it also has a strong commitment to public concerns surrounding such issues, and maintains a tone and point of address that seek to engage a general audience. -

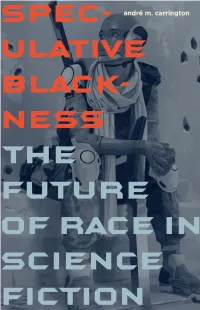

Speculative Blackness This Page Intentionally Left Blank Speculative Blackness

Speculative BlackneSS This page intentionally left blank SPECULATIVE BLACKNESS The Future of Race in Science Fiction andré m. carrington University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London A version of chapter 4 appeared as “Drawn into Dialogue: Comic Book Culture and the Scene of Controversy in Milestone Media’s Icon,” in The Blacker the Ink, ed. Frances Gateward and John Jennings (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2015). Por- tions of chapter 6 appeared as “Dreaming in Colour: Fan Fiction as Critical Reception,” in Race/Gender/Class/Media, 3d ed., ed. Rebecca Ann Lind (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson, 2013), 95–101; copyright 2013, printed and electronically reproduced by per- mission of Pearson Education, Inc. Copyright 2016 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401- 2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Carrington, André M. Speculative blackness: the future of race in science fiction / andré m. carrington. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8166-7895-2 (hc) ISBN 978-0-8166-7896-9 (pb) 1. American fiction—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Science fiction, American—History and criticism. 3. Race in literature. 4. African Americans in mass media. 5. African Americans in popular culture I. -

The Intellectual Functions of Gothic Fiction Paul Lewis

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1977 FEARFUL QUESTIONS, FEARFUL ANSWERS: THE INTELLECTUAL FUNCTIONS OF GOTHIC FICTION PAUL LEWIS Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation LEWIS, PAUL, "FEARFUL QUESTIONS, FEARFUL ANSWERS: THE INTELLECTUAL FUNCTIONS OF GOTHIC FICTION" (1977). Doctoral Dissertations. 1160. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1160 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

The Gothic in Children's Literature

THE GOTHIC IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE The Creation of the Adolescent in Crossover Fiction Duncan Burnes A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield School of English February 2016 1 ABSTRACT This thesis traces the literary course of gothic narrative elements as they appear within children’s fiction, beginning from the late eighteenth century and concluding at the close of the nineteenth century. The thesis presents evidence and potentialities for children’s appropriation of gothic fiction written for adults, and links them to the contemporaneous development of gothic devices in fiction written for children. These are argued to reflect a single phenomenon: The burgeoning relevance, literary and social, of the adolescent, in whom gothic and children’s fictions find a natural point of crossover. This thesis contextualises critical negativity towards the gothic and particularly to potential adolescent audiences, highlighting how contentious and therefore radical their relationship was. Nonetheless, the thesis introduces two hitherto obscure examples of early gothic children’s fiction from the end of the eighteenth century which provide initial evidence of this trend, alongside readings of parodic representations of adolescent gothic consumption. This is developed in an analysis of twelve early nineteenth-century gothic bluebooks, examples of short, cheap gothic fiction, for their relevance and, more significantly, accessibility to potential adolescent readers. This point suggests mechanisms by which the very means used to acquire fiction can foster the development of the adolescent social unit. The adolescent, or maturing child, is then considered as a specifically literary figure, with the character-type’s role, both in major canonical works of fiction and more esoteric texts aimed at narrower and often younger audiences, scrutinised for continuing gothic resonance particular to their immature age and experience. -

Utopian Philosophy As Literature and Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output Etherotopia, an ideal state and a state of mind : utopian philosophy as literature and practice http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/118/ Version: Full Version Citation: Callow, Christos (2015) Etherotopia, an ideal state and a state of mind : utopian philosophy as literature and practice. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2015 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email 1 Etherotopia, an Ideal State and a State of Mind: Utopian Philosophy as Literature and Practice Christos Callow Birkbeck, University of London PhD 2014 2 I, Christos Callow, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm this has been indicated in my thesis. ------------------------------------------------ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the concept of Etherotopia (which literally translates to ‗ethereal place‘), by which I define the combination of utopian philosophy with certain ideas of individual perfection such as nirvana. The argument is made that the separation of utopian visions into social utopias and individual ones (states and states of mind) is a false dilemma, since a complete utopian theory should include both. In relation to my own utopian writing and as a transition from the critical to the creative part of this thesis, I examine the question of genre in utopian literature and, following from the view that literary genres are subjective and conventional, I argue that utopian literature doesn‘t need to be labelled as a literary genre but rather that it is utopian philosophy in literary form, and therefore philosophical writing. -

Rades G Am E!

T A PARTY GAME IN he 3 ROUNDS FOR TWO CE OR MORE TEAMS. L CH EB A R R IT A Y D E S G A M E ! 60 12+ 3+ CONTENTS: 432 Cards, 30 second timer and score pad OBJECT: To score the most points by collecting names in 3 separate rounds. Quickplay:A game is played using a set of randomly chosen name cards. Each team gets 30 seconds to guess as many names as possible, with one player giving clues to his teammates. Players can always use sound effects and pantomime, but speech becomes more restricted as the game progresses: IN ROUND 1- Cluegivers can say anything. IN ROUND 2- Cluegivers can say only one word. IN ROUND 3- Cluegivers can’t say anything Each round ends when all names in the Deck of Fame have been guessed. All names are put back into the Deck for the next round. High score after the third round wins. 1 SETUP The only restrictions are: • No part or variant of the name can be used in the clue. Ex: You can’t use Divide into teams with team members sitting across from each other. Time’s “Willy” or “Bill” to get the Guesser to say WILLIAM. Up! works best when played in teams of two players each. (Three teams of two, for • “Rhymes with” clues are acceptable, provided the Cluegiver doesn’t actually example, is better than two teams of three.) With more than ten players, larger say the rhyming word. Ex: “Sounds like the animal that oinks” would be OK, teams will be necessary.