Maryland Historical Magazine, 1959, Volume 54, Issue No. 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

Address by the Honorable Edward H. Levi, Attorney General of the United

ADDRESS BY THE HONORABLE EDWARD H. LEVI ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES AT THE DEDICATION CEREMONIES OF THE JOHN EDGAR HOOVER BUILDING 11:00 A.M. TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 1975 J. EDGAR HOOVER BUILDING WASHINGTON, D. C. We have come together to dedicate this new building as the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. It is a proper moment to look back to the tradition of this law enforcement organization as well as to look forward to t.he future it will meet in this new place. It was under Theodore Roosevelt that the predecessor of the FBI was founded. There was resistance to its creation. For varied reasons -- noble and base -- some feared the idea of a federal' criminal investigative agency within the Justice Department. But through'the persistence of Attorney General Charles Joseph Bonaparte the organization was formed. The resistance did not crumble when Bonaparte's idea was accompli-shed. There were bad years to follow for the Bureau. It did not escape the tarnish of the Teapot Dome era. The Justice Department and the Bureau were criticized for failing to attack official corruption with sufficient vigor. From this period the' Bureau emerged with a new beginning under the man to whose memory this new building is dedicated. John Edgar Hoover was 29 years old when Attorney General Harlan Fiske Stone appointed him acting director of the Bureau in May of 1924. Hoover's reputation of scrupulous honesty had been commended to Stone. Such a man was needed. Hoover set about reforming the Bureau to meet the demanding requirements of a more complicated era. -

Volume 89 Number 1 March 2020 V Olume 89 Number 1 March 2020

Volume 89 Volume Number 1 March 2020 Volume 89 Number 1 March 2020 Historical Society of the Episcopal Church Benefactors ($500 or more) President Dr. F. W. Gerbracht, Jr. Wantagh, NY Robyn M. Neville, St. Mark’s School, Fort Lauderdale, Florida William H. Gleason Wheat Ridge, CO 1st Vice President The Rev. Dr. Thomas P. Mulvey, Jr. Hingham, MA J. Michael Utzinger, Hampden-Sydney College Mr. Matthew P. Payne Appleton, WI 2nd Vice President The Rev. Dr. Warren C. Platt New York, NY Robert W. Prichard, Virginia Theological Seminary The Rev. Dr. Robert W. Prichard Alexandria, VA Secretary Pamela Cochran, Loyola University Maryland The Rev. Dr. Gardiner H. Shattuck, Jr. Warwick, RI Treasurer Mrs. Susan L. Stonesifer Silver Spring, MD Bob Panfil, Diocese of Virginia Director of Operations Matthew P. Payne, Diocese of Fond du Lac Patrons ($250-$499) [email protected] Mr. Herschel “Vince” Anderson Tempe, AZ Anglican and Episcopal History The Rev. Cn. Robert G. Carroon, PhD Hartford, CT Dr. Mary S. Donovan Highlands Ranch, CO Editor-in-Chief The Rev. Cn. Nancy R. Holland San Diego, CA Edward L. Bond, Natchez, Mississippi The John F. Woolverton Editor of Anglican and Episcopal History Ms. Edna Johnston Richmond, VA [email protected] The Rev. Stephen A. Little Santa Rosa, CA Church Review Editor Richard Mahfood Bay Harbor, FL J. Barrington Bates, Prof. Frederick V. Mills, Sr. La Grange, GA Diocese of Newark [email protected] The Rev. Robert G. Trache Fort Lauderdale, FL Book Review Editor The Rev. Dr. Brian K. Wilbert Cleveland, OH Sheryl A. Kujawa-Holbrook, Claremont School of Theology [email protected] Anglican and Episcopal History (ISSN 0896-8039) is published quarterly (March, June, September, and Sustaining ($100-$499) December) by the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church, PO Box 1301, Appleton, WI 54912-1301 Christopher H. -

John AJ Creswell of Maryland

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 2015 Forgotten Abolitionist: John A. J. Creswell of Maryland John M. Osborne Dickinson College Christine Bombaro Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Osborne, John M., and Christine Bombaro. Forgotten Abolitionist: John A. J. Creswell of Maryland. Carlisle, PA: House Divided Project at Dickinson College, 2015. https://www.smashwords.com/books/ view/585258 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forgotten Abolitionist: John A.J. Creswell of Maryland John M. Osborne and Christine Bombaro Carlisle, PA House Divided Project at Dickinson College Copyright 2015 by John M. Osborne and Christine Bombaro Distributed by SmashWords ISBN: 978-0-9969321-0-3 License Notes: This book remains the copyrighted property of the authors. It may be copied and redistributed for personal use provided the book remains in its complete, original form. It may not be redistributed for commercial purposes. Cover design by Krista Ulmen, Dickinson College The cover illustration features detail from the cover of Harper's Weekly Magazine published on February 18, 1865, depicting final passage of Thirteenth Amendment on January 31, 1865, with (left to right), Congressmen Thaddeus Stevens, William D. Kelley, and John A.J. Creswell shaking hands in celebration. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Matthew Pinsker Introduction Marylander Dickinson Student Politician Unionist Abolitionist Congressman Freedom’s Orator Senator Postmaster General Conclusion Afterword Notes Bibliography About the Authors FOREWORD It used to be considered a grave insult in American culture to call someone an abolitionist. -

Historian J Michael Cobb Shares Stories and Plans

Media Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 26, 2019 Contact: Leslie Baker, 757/728-5316 [email protected] Seamus McGrann, 757/727-6841 [email protected] Historian J Michael Cobb Shares Stories and Plans for Renovation of Fort Wool at the Hampton History Museum on August 5 HAMPTON, Va -Author, historian and former Hampton History Museum curator J Michael Cobb shares the fascinating story of Fort Wool, its history, and what lies ahead for the future of the venerable fortress, as part of the Hampton History Museum’s Port Hampton Lecture Series on Monday, August 5, 2019 7:00 p.m.-8:00 p.m. A familiar site to commuters crossing the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel, Fort Wool, originally named Fort Calhoun, has been a patriotic symbol of freedom since its construction in 1819. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1969, Fort Wool is a visible landmark at the gateway to Hampton Roads. Like Fort Monroe, it is an important asset of Hampton, the Commonwealth, and the nation. A unique site tells the history of America following the War of 1812 through World War II. Enslaved men took part in the building of Fort Wool. Robert E. Lee oversaw construction of the fortification. Andrew Jackson governed America for extended periods from the island. Fort Wool took part in the epic Civil War Battle of the “Monitor” and “Virginia.” Abraham Lincoln watched the attempt to capture Norfolk from the ramparts of Fort Wool; and Fort Wool was part of the Chesapeake Bay defenses during World War II. It continued to serve until the Army decommissioned it in the 1970s. -

1905-1906 Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University

OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during: the Academical Year ending in JUNE, /9O6, INCLUDING THE RECORD OF A FEW WHO DIED PREVIOUSLY, HITHERTO UNREPORTED [Presented at the meeting of the Alumni, June 26, 1906] [No 6 of the Fifth Printed Series, and No 65 of the whole Record] OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during the Academical year ending in JUNE, 1906 Including the Record of a few who died previously, hitherto unreported [PRESENTED AT THE MEETING OF THE ALUMNI, JUNE 26, 1906] I No 6 of the Fifth Printed Series, and No 65 of the whole Record] YALE COLLEGE (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1831 JOSEPH SELDEN LORD, since the death of Professor Samuel Porter of the Class of 1829, m September, 1901, the oldest living graduate of^Yale University, and since the death of Bishop Clark m September, 1903, the last survivor of his class, was born in Lyme, Conn, April 26, 1808. His parents were Joseph Lord, who carried on a coasting trade near Lyme, and Phoebe (Burnham) Lord. He united with the Congregational church m his native place when 16 years old, and soon began his college preparation in the Academy of Monson, Mass., with the ministry m view. Commencement then occurred in September, and after his graduation from Yale College, he taught two years in an academy at Bristol, Conn He then entered the Yale Divinity School, was licensed to preach by the Middlesex Congregational Association of Connecticut in 1835, and completed his theological studies in 1836. After supplying 522 the Congregational church in -

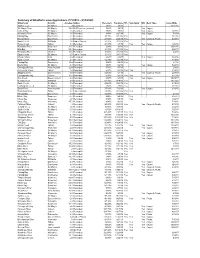

Summary of Lease Applications 9-23-20.Xlsx

Summary of Shellfish Lease Applications (1/1/2015 - 9/23/2020) Waterbody County AcreageStatus Received CompleteTFL Sanctuary WC Gear Type IssuedDate Smith Creek St. Mary's 3 Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 11/21/16 St. Marys River St. Mary's 16.2 GISRescreen (revised) 1/6/15 1/6/15 Yes Cages Calvert Bay St. Mary's 2.5Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 YesCages 2/28/17 Wicomico River St. Mary's 4.5Recorded 1/8/15 1/27/15 YesCages 5/8/19 Fishing Bay Dorchester 6.1 Recorded 1/12/15 1/12/15 Yes 11/2/15 Honga River Dorchester 14Recorded 2/10/15 2/26/15Yes YesCages & Floats 6/27/18 Smith Creek St Mary's 2.6 Under Protest 2/12/15 2/12/15 Yes Harris Creek Talbot 4.1Recorded 2/19/15 4/7/15 Yes YesCages 4/28/16 Wicomico River Somerset 26.7Recorded 3/3/15 3/3/15Yes 10/20/16 Ellis Bay Wicomico 69.9Recorded 3/19/15 3/19/15Yes 9/20/17 Wicomico River Charles 13.8Recorded 3/30/15 3/30/15Yes 2/4/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 1.7 Under Protest 3/31/15 3/31/15 Yes Chester River Kent 4.9Recorded 4/6/15 4/9/15 YesCages 8/23/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 2.1 Recorded 4/23/15 4/23/15 Yes 9/19/16 Fishing Bay Dorchester 12.4Recorded 5/4/15 6/4/15Yes 6/1/16 Breton Bay St. -

WI-578 Governor E. E. Jackson House, the Oaks,Site

WI-578 Governor E. E. Jackson House, The Oaks,site Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 08-29-2003 WI-578 1883-84, 1905 The Oaks Salisbury (Site) Private The last decades of the nineteenth century were particularly prosperous ones for the citizens of Salisbury, who had built up over the course of twenty years the largest commercial, industrial, and trading center on the peninsula south of Wilmington, Delaware. The most ambitious domestic construction project during the early 1880s was the design and assemblage of the sprawling Shingle-style mansion for Elihu Emory Jackson and Nellie Rider Jackson on a large parcel of land bordering North Division and West Isabella streets. -

1823 Journal of General Convention

Journal of the Proceedings of the Bishops, Clergy, and Laity of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America in a General Convention 1823 Digital Copyright Notice Copyright 2017. The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America / The Archives of the Episcopal Church All rights reserved. Limited reproduction of excerpts of this is permitted for personal research and educational activities. Systematic or multiple copy reproduction; electronic retransmission or redistribution; print or electronic duplication of any material for a fee or for commercial purposes; altering or recompiling any contents of this document for electronic re-display, and all other re-publication that does not qualify as fair use are not permitted without prior written permission. Send written requests for permission to re-publish to: Rights and Permissions Office The Archives of the Episcopal Church 606 Rathervue Place P.O. Box 2247 Austin, Texas 78768 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 512-472-6816 Fax: 512-480-0437 JOURNAL .. MTRJI OJr TllII "BISHOPS, CLERGY, AND LAITY O~ TIU; PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCH XII TIIJ! UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Xif A GENERAL CONVENTION, Held in St. l'eter's Church, in the City of Philadelphia, from the 20th t" .the 26th Day of May inclusive, A. D. 1823. NEW· YORK ~ PlllNTED BY T. lit J. SWURDS: No. 99 Pearl-street, 1823. The Right Rev. William White, D. D. of Pennsylvania, Pre siding Bishop; The Right Rev. John Henry Hobart, D. D. of New-York, The Right Rev. Alexander Viets Griswold, D. D. of the Eastern Diocese, comprising the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusct ts, Vermont, and Rhode Island, The Right Rev. -

The D.C. Freeway Revolt and the Coming of Metro Sidebar U.S. 50: the Roads Between Annapolis, MD, and Washington, DC

The D.C. Freeway Revolt and the Coming of Metro Sidebar U.S. 50: The Roads Between Annapolis, MD, and Washington, DC Table of Contents From the Early Days ....................................................................................................................... 2 The Old Stage Road ........................................................................................................................ 2 Central Avenue ............................................................................................................................... 5 Maryland’s Good Roads Movement ............................................................................................... 6 Promoting the National Defense Highway ................................................................................... 11 Battle of the Letters ....................................................................................................................... 15 The Legislature Moves On ............................................................................................................ 19 Lost in the Lowlands ..................................................................................................................... 21 Getting to Construction ................................................................................................................. 24 Moving Forward ........................................................................................................................... 30 Completed .................................................................................................................................... -

2019-Symposium-Booklet.Pdf

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Abstracts ................................................................................................................................................ 2 COLLEGE OF BUSINESS Department of Management ....................................................................................................................... 3 Department of Marketing and Finance ........................................................................................................ 5 COLLEGE OF EDUCATION Department of Kinesiology and Recreation ................................................................................................. 6 COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES Department of Biology ............................................................................................................................... 10 Department of Chemistry ........................................................................................................................... 25 Department of Communication ................................................................................................................. 28 Department of Computer Science and Information Technologies ............................................................ 29 Department of English and Foreign Languages .......................................................................................... 31 Department of Geography ......................................................................................................................... 39 Department -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936