A Clinical Case Study in Banking Failure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Economy Watch AIB Treasury Economic Research Unit

Irish Economy Watch AIB Treasury Economic Research Unit Thursday 19 November 2020 Mar-20 Apr-20 May-20 Jun-20 Jul-20 Aug-20 Sep-20 Oct-20 Manufacturing PMI edged higher to 50.3 in October as the MANUFACTURING survey points to broadly stable AIB Manufacturing PMI 45.1 36.0 39.2 51.0 57.3 52.3 50.0 50.3 but subdued business conditions in the sector OECD Leading Indicator 98.8 93.4 94.1 97.6 99.2 99.4 99.6 99.7 Traditional industrial production Industrial Production (Ex-Modern) 112.7 86.5 82.6 93.7 110.8 109.5 110.6 #N/A moved higher in September as Production (Ex-Modern) : 3mma YoY% 1.7 -10.0 -17.7 -21.2 -14.2 -5.3 -0.7 #N/A output rebounded by 25.9% in 3mth / 3mth % seas. adj. 2.4 -9.6 -16.3 -22.9 -6.6 11.4 25.9 #N/A Q3. YoY growth rate at –0.7% SERVICES / RETAIL Services PMI stayed in contraction but improved to 48.3 AIB Services PMI 32.5 13.9 23.4 39.7 51.9 52.4 45.8 48.3 in October. Weak demand was evident from a decline in new CSO Services Index (Value) 124.4 98.1 101.0 114.1 114.5 115.1 121.1 #N/A business, with firms linking this - YoY % -0.4 -21.8 -19.3 -10.5 -10.6 -9.1 -4.0 #N/A to Covid-19 restrictions - 3mth / 3mth % seas. -

You Can View the Full Spreadsheet Here

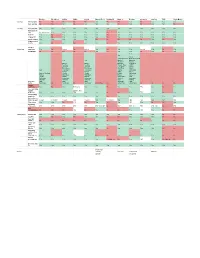

Barclays First Direct Halifax HSBC Lloyds Monzo (Free) Nationwide Natwest Revolut Santander Starling TSB Virgin Money Savings Savings pots No No No No No Yes No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Auto savings No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes No Banking Easy transfer yes Yes yes Yes yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New payee in app Need debit card Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes change SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes pay in cheque Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No Yes No Yes share account details Yes No yes No yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Analyse Budgeting spending Yes No limited No limited Yes No Yes Yes Limited Yes No Yes Set Budget No No No No No Yes No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Amex Allied Irish Bank Bank of Scotland Yes Yes Bank of Barclays Scotland Danske Bank of Bank of Barclays First Direct Scotland Scotland Danske Bank HSBC Barclays Barclays First Direct Halifax Barclaycard Barclaycard First Trust Lloyds Yes First Direct First Direct Halifax M&S Bank Halifax Halifax HSBC Monzo Bank of Scotland Lloyds Lloyds Lloyds Nationwide Halifax M&S Bank M&S Bank Monzo Natwest Lloyds MBNA MBNA Nationwide RBS Nationwide Nationwide Nationwide NatWest Santander NatWest NatWest NatWest RBS Starling Add other RBS RBS RBS Santander TSB banks Santander No Santander No Santander Not on free No Ulster Bank Ulster Bank No No No No Instant notifications Yes No Yes Rolling out Yes Yes No Yes Yes TBC Yes No Yes See upcoming regular Balance After payments -

Allied Irish Bank (GB) Comes Top Again in Comprehensive UK Banking Survey 27Th November 2000

Allied Irish Bank (GB) comes top again in comprehensive UK banking survey 27th November 2000 Allied Irish Bank (GB) has today been named Best Business Bank for the fourth consecutive time in the Forum of Private Business’s (FPB) comprehensive survey into the strength of service offered by banks to private businesses. The FPB report, Private Businesses and Their Banks 2000, is a biennial survey of tens of thousands of British businesses and shows that Allied Irish Bank (GB) has maintained its No. 1 position over other major UK banks since 1994. Aidan McKeon, General Manager of Allied Irish Bank (GB) and Managing Director AIB Group (UK) p.l.c., commented: "While we are delighted to win this award for the fourth time, we are far from complacent. We continue to listen closely to our customers and to invest in the cornerstones of our business: recruiting, training and retaining quality people; building 'true’ business relationships; and ongoing commitment to maintaining short lines of decision making. At the same time, we are exploiting technology to make our service as customer- responsive and efficient as possible." Allied Irish Bank (GB), one of the forerunners in relationship banking, scores highest in the survey for knowledge and understanding. The bank also scored highly on efficiency, reliability and customer satisfaction. Mr. McKeon continued: "We recognise that business customers have particular needs and concerns and we are always striving to ensure that our customers receive a continually improved service. We shall look carefully at this survey and liaise with our customers to further strengthen our service." Stan Mendham, Chief Executive of the FPB commented: "The FPB congratulates Allied Irish Bank (GB) on being voted Best Business Bank in Britain for the fourth time. -

Irish Economy Note No. 13 “Did the ECB Cause a Run on Irish Banks

Irish Economy Note No. 13 “Did the ECB Cause a Run on Irish Banks? Evidence from Disaggregated Data” Gary O’Callaghan Dubrovnik International University February 2011 www.irisheconomy.ie/Notes/IrishEconomyNote13.pdf Did the ECB Cause a Run on Irish Banks? Evidence from the Disaggregated Data. Gary O’Callaghan Dubrovnik International University February 2011 The paper closely examines events leading up to the Irish crisis of November 2010. It traces the effects of these events on both the onshore banking sector and on an offshore sector that is almost as large but is very different in terms of structure and commitment. Both sectors benefit from liquidity support by the European Central Bank (ECB) but the offshore sector does not benefit from a Government guarantee on deposits and securities and no bank in this category would expect to be recapitalised by the Irish Government in the event of its insolvency. Therefore, by examining the effects of certain events on deposits in each sector, one can distinguish between a crisis of confidence in monetary support (that would apply to both sectors) and an erosion of credibility in fiscal policy (that would apply to domestic banks only). The paper suggests that a systemic run on Irish banks was the proximate cause of the November crisis (even if a financing package might have been needed anyway) and that it probably resulted from public musings by ECB Council members on the need to curtail liquidity support to banks. An ECB commitment in May to support government bonds had undermined its ability to reign in monetary policy and left it searching for an exit. -

Annual-Financial-Report-2009.Pdf

Contents 4 Chairman’s statement 255 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities in relation to the Accounts 6 Group Chief Executive’s review 256 Independent auditor’s report 8 Corporate Social Responsibility 258 Additional information 12 Financial Review 276 Principal addresses - Business description 278 Index - Financial data - 5 year financial summary - Management report - Capital management - Critical accounting policies - Deposits and short term borrowings - Financial investments available for sale - Financial investments held to maturity - Contractual obligations - Off balance sheet arrangements 59 Risk Management - Risk Factors - Framework - Individual risk types - Supervision and regulation 106 Corporate Governance - The Board & Group Executive Committee - Directors’ Report - Corporate Governance statement - Employees 119 Accounting policies 136 Consolidated income statement 137 Balance sheets 139 Statement of cash flows 141 Statement of recognised income and expense 142 Reconciliations of movements in shareholders’ equity 146 Notes to the accounts 1 Forward-Looking Information This document contains certain forward-looking statements within the meaning of the United States Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 with respect to the financial condition, results of operations and business of the Group and certain of the plans and objectives of the Group. In particular, among other statements, certain statements in the Chairman’s statement, the Group Chief Executive’s review, and the Financial Review and Risk Management sections, with regard to management objectives, trends in results of operations, margins, risk management, competition and the impact of changes in International Financial Reporting Standards are forward-looking in nature.These forward-looking statements can be identified by the fact that they do not relate only to historical or current facts. -

The Ritz London, 16Th November 2016 by Invitation Only Confidential – Not for Distribution

® The Ritz London, 16th November 2016 By Invitation Only The AI Finance Summit is the world’s first and only high-level conference exploring the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the financial services industry. The invitation-only event, brings together CxOs from the world’s leading banks, insurance companies, asset management organisations, brokers. The event takes place at London’s most prestigious address, The Ritz, on the 16th of November and features world-class speakers presenting exclusive case studies shedding light into how the 4th industrial revolution will affect specifically affect the financial services industry. DRAFT AGENDA 16tH November 2016, The Ritz London 08:30 Registration, Breakfast refreshments & Networking 09:15 A welcome unlike any other… and Chair’s Opening Remarks 09:20 State of Play opening keynote: the 4th industrial revolution in financial services Where are financial services currently at with artificial intelligence, what technologies in particular are being used, how quickly is it being adopted, and what areas are leading the adoption of new intelligent technologies? These are are some of the pivotal questions answered in the scene-setting opening keynote to the AI Finance Summit. 09:45 Introducing a new era of risk management in investment banking The use of artificial intelligence within the world of investment banking is a phenomenon which is going to propel the industry in more ways than one. This talk will discuss how the advent of AI technologies, focusing on machine learning and cognitive computing, will drastically enhance risk management processes and achieve levels of accuracy previously unseen in the industry 10:10 Customer Experience/ Relations Management through AI platforms AI is revolutionizing customer service across every industry, with financial services already a pioneer in adoption. -

Valuations for Lenders – Our Specialist Area of Business

Valuations for Lenders – Our Specialist Area of Business William Newsom –Head of Valuation, Savills Commercial Limited Presentation • Savills’Corporate Profile Contents • Commercial Valuation Department –Areas of Expertise • Why instruct Savills? Savills’ • July 1988 –Savills plc listed on the London Corporate Profile Stock Exchange • 2006 –Ranked number 1 (see over) • 98 offices in UK; 25 in Europe and 36 in Far East and Australasia, etc. • Savills commercial UK turnover in 2006 was £189.1M (56.4% of total UK company turnover) No. 1 by turnover July 2006 No. 1 by turnover June 2006 No. 1 employer May 2006 Savills Commercial Limited -UK Fee Income by Product Area 2006 Savills’accolades: Investment •Voted Investment Agent of the Year 33% 2005 (and 2003) Property 47% •Voted Residential Development Agent Management of the Year 2004 Agency •Winners of Industrial and Retail Agency Teams of the Year 2007 - Professional 7% North West Property Awards Services (inc. 13% Valuation) •Nominated as Professional Agency (Valuation) of the Year 2006 •Nominated as Scottish Professional Agency (Valuation) of the Year 2006 (winner to be announced in May 2007) Commercial • Total staff in London of 38 Valuation • Total billing in 2005 of £10.5M Department • Plus commercial valuersin Edinburgh and Manchester, soon to open in Birmingham • 11 Directors • Core Directors average 15+ years service each • 18 new staff in London over 2005/2006 • We specialisein larger commercial property (above £5.0M). Often above £100M • Minimum fee £4,000 per instruction Commercial -

In Brief/简介- A&L Goodbody's China Focus

In Brief/简介 A&L Goodbody’s China Focus A&L Goodbody聚焦中国 A&L Goodbody is internationally recognised as one of Ireland’s leading law firms. We are continually instructed on the most significant, high value and complex legal work in Ireland. Our culture is to instinctively collaborate for the success of our clients. This enables us to deliver the highest quality solutions for our clients, in ways others may not think of. A&L Goodbody是国际公认的爱尔兰顶级律师事务所之一,多年来在爱尔兰一直致力于最重要、高价值及复杂的法律工作。我 们的理念即是为了客户的成功进行合作。这使得我们能够向客户提供无以伦比的高质量解决方案。 Established more than 100 years ago, we are an “all-island” law firm with offices in Dublin and Belfast. We also have offices in London, New York and Palo Alto and a particular focus on China. 本所创立于100年以前, 是一家在都柏林和贝尔法斯特设立办公室并覆盖全岛的律师事务所。我们在伦敦、纽约和帕罗奥多市也 设有办公室, 并且尤其关于中国。 The Firm provides a full range of market-leading business legal services through our corporate, banking and financial services, corporate tax, litigation and dispute resolution, commercial property, employment, pensions and benefits departments. The Firm offers the most extensive range of specialist services available in Ireland through our 30 Specialist Practice Groups. 我们提供市场领先的全方位法律服务,下设公司部、银行和融资服务部、公司税法部、诉讼和争议解决部、商业房地产部、劳动 部、退休金及福利部等多个部门。我们拥有 30 多个专业团队,向客户提供最广泛的爱尔兰法律专业服务。 A&L Goodbody is one of Ireland’s largest and most successful law firms with an extensive and top class client list, representing hundreds of internationally know names and global blue chip corporations across all industry sectors including General Electric, Pfizer, Genzyme, Ranbaxy, Citi Group, Barclays, RBS, JP Morgan, CSFB, UBS, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Northern Trust, Apple, Microsoft, IBM, Intel, Scientific Games, Kraft, Nestle, Yoplait, Tesco, Heineken, Pernod Ricard, Campari, Anglo American Corporation, Airbus, Aviva, Zurich, XL, Munich Re, KPMG and Ernst&Young, many of whom have operations in China as well as Ireland. -

20170518 Ministers Brief

MIN ISTER’S BRIEF JUNE 2017 Page 1 of 252 Page 2 of 252 MINISTER'S BRIEF JUNE 2017 Page 3 of 252 Contents > Page 4 of 252 1. INTRODUCTION 8 2. BUSINESS [POLICY] PRIORITIES 2017 10 2.1 ECONOMIC & FISCAL DIRECTORATE - BUSINESS PLAN POLICY PRIORITIES 11 2.2 FINANCE AND BANKING DIRECTORATE - BUSINESS PLAN POLICY PRIORITIES 13 GLOSSARY OF INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS/COMMITTEES 15 3. DETAILED BRIEFING 30 3.1 ECONOMIC AND FISCAL DIRECTORATE 31 3.1.2 ECONOMIC DIVISION 32 3.1.2.1 Macroeconomic analysis and forecasting 33 3.1.2.2 Microeconomic analysis underpinning taxation and other policies and sectoral policy economic analysis 39 3.1.2.3 Economic coordination including development and monitoring of economic strategy 44 3.1.2.4 Budgetary/fiscal policy, governance, reporting, coordination and production of Budget; tax revenue forecasting; general government statistics - reporting, forecasting and classification advice 49 3.1.3 TAX DIVISION 55 3.1.3.1 General income tax policy and reform 61 3.1.3.2 Excise duties, customs issues, value added tax, EU and national indirect taxes, and associated tax policy issues 73 3.1.3.3 Capital Taxes and EU State Aid Matters 82 3.1.3.4 International and corporation tax policy 87 3.1.3.5 Tax Administration, Revenue Powers, Local Property Tax, Pension Taxation, Stamp Duty and Tax Appeals 93 3.1.4 EU & INTERNATIONAL DIVISION 99 3.1.4.1 Brexit Unit 100 3.1.4.2 EU-IMF Post Programme Monitoring & Surveillance/ EU Lending instruments & Programme Loans/ European Stability Mechanism Policy, and EU Budget 103 3.1.4.3 EU policy -

The Bail out Business Who Profi Ts from Bank Rescues in the EU?

ISSUE BRIEF The Bail Out Business Who profi ts from bank rescues in the EU? Sol Trumbo Vila and Matthijs Peters 7 AUTHOR: Sol Trumbo Vila and Matthijs Peters EDITORS: Denis Burke DESIGN: Brigitte Vos GRAPHS AND INFOGRAPHICS: Karen Paalman Published by Transnational Institute – www.TNI.org February 2017 Contents of the report may be quoted or reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that the source of information is properly cited. TNI would appreciate receiving a copy or link of the text in which this document is used or cited. Please note that for some images the copyright may lie elsewhere and copyright conditions of those images should be based on the copyright terms of the original source. http://www.tni.org/copyright ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank Alvaro, Joel, Kenneth, Santi, Vica and Walden for their insightful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of the report. 2 | The Bail-Out Business Table of contents Executive Summary 4 Introduction 5 GRAPH Permanent losses for rescue packages between 2008-2015 7 1 The Bail Out Business in the EU 8 1.1 Understanding the bail outs in the EU 8 Info box 1: How to rescue a bank? 9 1.2 Case Studies Bail Out Business 10 Info box 2: Saving German Banks 14 1.3 The role of the audit firms in the Bail Out Business 15 Info box 3: Tax avoidance through the Big Four 19 1.4 The role of the financial consultants in the Bail Out Business 19 Info box 4: BlackRock, Lazard and Chinese Walls 22 2 New EU regulation and the Bail Out Business in the EU 23 2.1 Can the Big Four continue with “business as usual” in the EU? 24 2.2 What are the implications of the Banking Union for the Bail Out Business? 25 Info box 5: Bank bail out versus bail in 26 Info box 6: An alternative to restore public capacity: public banks 27 3 Conclusions 28 References 29 The Bail-Out Business | 3 Executive Summary Since the 2008 financial crisis, European citizens have grown accustomed to the idea that public money can be used to rescue financial institutions from bankruptcy. -

ELA, Promissory Notes and All That: the Fiscal Costs of Anglo Irish Bank

ELA, Promissory Notes and All That: The Fiscal Costs of Anglo Irish Bank Karl Whelan University College Dublin Revised Draft, September 2012 Abstract: This paper describes the cost to the Irish state of its bailout of the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation (IBRC). The paper discusses the IBRC’s balance sheet, its ELA debts to the Central Bank of Ireland and the promissory notes provided to it by the Irish government to pay off its liabilities. Options for reducing these costs are discussed. 1. Introduction The Irish state has committed an extraordinary €64 billion—about 40 percent of GDP—towards bailing out its banking sector. €30 billion of this commitment has gone towards acquiring almost complete ownership of Allied Irish Banks and Irish Life and Permanent and partial ownership of Bank of Ireland. 1 It is possible that some fraction of this outlay may be recouped at some point in the future via sales of these shares to the private sector. In contrast, the remaining €35 billion that relates to Irish Bank Resolution Corporation (IBRC), the entity that has merged Anglo Irish Bank and Irish Nationwide Building Society, is almost all “dead money” that will never be returned to the state. Much of the commentary on Ireland’s bank bailout has focused on the idea that the Irish government should change its policy in relation to payment of unsecured IBRC bondholders. However, the amount of IBRC bondholders remaining is small when compared with the total cost of bailing out these institutions. Instead, the major debt burden due to the IBRC relates to promissory notes provided to it by the Irish government, which in turn are largely being used to pay off so-called Exceptional Liquidity Assistance (ELA) loans that have been provided by the Central Bank of Ireland. -

Information Memorandum ALLIED IRISH BANKS, P.L.C

Information Memorandum ALLIED IRISH BANKS, p.l.c. €5,000,000,000 Euro-Commercial Paper Programme Rated by Standard & Poor’s Credit Market Services Europe Limited and Fitch Ratings Ltd. Arranger UBS INVESTMENT BANK Issuing and Paying Agent CITIBANK Dealers AIB BARCLAYS BOFA MERRILL LYNCH CITIGROUP CREDIT SUISSE GOLDMAN SACHS INTERNATIONAL ING NOMURA THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND UBS INVESTMENT BANK The date of this Information Memorandum is 16 March 2016 Disclaimer clauses for Dealers, Issuing and Paying Agent and Arranger See the section entitled “Important Notice” on pages 1 to 4 of this Information Memorandum. IMPORTANT NOTICE This Information Memorandum (together with any supplementary information memorandum, and information incorporated herein by reference, the “Information Memorandum”) contains summary information provided by Allied Irish Banks, p.l.c. (the “Issuer” or “AIB”) in connection with a euro-commercial paper programme (the “Programme”) under which the Issuer acting through its office in Dublin or its London branch as set out at the end of this Information Memorandum may issue and have outstanding at any time euro-commercial paper notes (the “Notes”) up to a maximum aggregate amount of €5,000,000,000 or its equivalent in alternative currencies. Under the Programme, the Issuer may issue Notes outside the United States pursuant to Regulation S (“Regulation S”) under the United States Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”). The Issuer has, pursuant to an amended and restated dealer agreement dated 16 March 2016 (the “Dealer Agreement”), appointed UBS Limited as arranger of the Programme (the “Arranger”), appointed Bank of America Merrill Lynch International Limited, Barclays Bank PLC, Citibank Europe plc, London Branch, Credit Suisse Securities (Europe) Limited, Goldman Sachs International, ING Bank N.V., Nomura International plc, The Royal Bank of Scotland plc and UBS Limited as dealers in respect of the Notes (together with Allied Irish Banks, p.l.c.