AUTHOR Wagner, Elaine the Vision of Sequoyah: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cherokee Ethnogenesis in Southwestern North Carolina

The following chapter is from: The Archaeology of North Carolina: Three Archaeological Symposia Charles R. Ewen – Co-Editor Thomas R. Whyte – Co-Editor R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. – Co-Editor North Carolina Archaeological Council Publication Number 30 2011 Available online at: http://www.rla.unc.edu/NCAC/Publications/NCAC30/index.html CHEROKEE ETHNOGENESIS IN SOUTHWESTERN NORTH CAROLINA Christopher B. Rodning Dozens of Cherokee towns dotted the river valleys of the Appalachian Summit province in southwestern North Carolina during the eighteenth century (Figure 16-1; Dickens 1967, 1978, 1979; Perdue 1998; Persico 1979; Shumate et al. 2005; Smith 1979). What developments led to the formation of these Cherokee towns? Of course, native people had been living in the Appalachian Summit for thousands of years, through the Paleoindian, Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippi periods (Dickens 1976; Keel 1976; Purrington 1983; Ward and Davis 1999). What are the archaeological correlates of Cherokee culture, when are they visible archaeologically, and what can archaeology contribute to knowledge of the origins and development of Cherokee culture in southwestern North Carolina? Archaeologists, myself included, have often focused on the characteristics of pottery and other artifacts as clues about the development of Cherokee culture, which is a valid approach, but not the only approach (Dickens 1978, 1979, 1986; Hally 1986; Riggs and Rodning 2002; Rodning 2008; Schroedl 1986a; Wilson and Rodning 2002). In this paper (see also Rodning 2009a, 2010a, 2011b), I focus on the development of Cherokee towns and townhouses. Given the significance of towns and town affiliations to Cherokee identity and landscape during the 1700s (Boulware 2011; Chambers 2010; Smith 1979), I suggest that tracing the development of towns and townhouses helps us understand Cherokee ethnogenesis, more generally. -

Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2017 Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves Beau Duke Carroll University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Recommended Citation Carroll, Beau Duke, "Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4985 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Beau Duke Carroll entitled "Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Jan Simek, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: David G. Anderson, Julie L. Reed Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Talking Stone: Cherokee Syllabary Inscriptions in Dark Zone Caves A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Beau Duke Carroll December 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Beau Duke Carroll All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the following people who contributed their time and expertise. -

Runes Free Download

RUNES FREE DOWNLOAD Martin Findell | 112 pages | 24 Mar 2014 | BRITISH MUSEUM PRESS | 9780714180298 | English | London, United Kingdom Runic alphabet Main article: Younger Futhark. He Runes rune magic to Freya and learned Seidr from her. The runes were in use among the Germanic peoples from the 1st or 2nd century AD. BCE Proto-Sinaitic 19 c. They Runes found in Scandinavia and Viking Age settlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. From the "golden age of philology " in the 19th century, runology formed a specialized branch of Runes linguistics. There are no horizontal strokes: when carving a message on a flat staff or stick, it would be along the grain, thus both less legible and more likely to split the Runes. BCE Phoenician 12 c. Little is known about the origins of Runes Runic alphabet, which is traditionally known as futhark after the Runes six letters. That is now proved, what you asked of the runes, of the potent famous ones, which the great gods made, and the mighty sage stained, that it is best for him if he stays silent. It was the main alphabet in Norway, Sweden Runes Denmark throughout the Viking Age, but was largely though not completely replaced by the Latin alphabet by about as a result of the Runes of Runes of Scandinavia to Christianity. It was probably used Runes the 5th century Runes. Incessantly plagued by maleficence, doomed to insidious death is he who breaks this monument. These inscriptions are generally Runes Elder Futharkbut the set of Runes shapes and bindrunes employed is far from standardized. -

Cherokees in Arkansas

CHEROKEES IN ARKANSAS A historical synopsis prepared for the Arkansas State Racing Commission. John Jolly - first elected Chief of the Western OPERATED BY: Cherokee in Arkansas in 1824. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum LegendsArkansas.com For additional information on CNB’s cultural tourism program, go to VisitCherokeeNation.com THE CROSSING OF PATHS TIMELINE OF CHEROKEES IN ARKANSAS Late 1780s: Some Cherokees began to spend winters hunting near the St. Francis, White, and Arkansas Rivers, an area then known as “Spanish Louisiana.” According to Spanish colonial records, Cherokees traded furs with the Spanish at the Arkansas Post. Late 1790s: A small group of Cherokees relocated to the New Madrid settlement. Early 1800s: Cherokees continued to immigrate to the Arkansas and White River valleys. 1805: John B. Treat opened a trading post at Spadra Bluff to serve the incoming Cherokees. 1808: The Osage ceded some of their hunting lands between the Arkansas and White Rivers in the Treaty of Fort Clark. This increased tension between the Osage and Cherokee. 1810: Tahlonteeskee and approximately 1,200 Cherokees arrived to this area. 1811-1812: The New Madrid earthquake destroyed villages along the St. Francis River. Cherokees living there were forced to move further west to join those living between AS HISTORICAL AND MODERN NEIGHBORS, CHEROKEE the Arkansas and White Rivers. Tahlonteeskee settled along Illinois Bayou, near NATION AND ARKANSAS SHARE A DEEP HISTORY AND present-day Russellville. The Arkansas Cherokee petitioned the U.S. government CONNECTION WITH ONE ANOTHER. for an Indian agent. 1813: William Lewis Lovely was appointed as agent and he set up his post on CHEROKEE NATION BUSINESSES RESPECTS AND WILL Illinois Bayou. -

The Free State of Winston"

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2019 Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston" Susan Neelly Deily-Swearingen University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Deily-Swearingen, Susan Neelly, "Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston"" (2019). Doctoral Dissertations. 2444. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2444 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REBEL REBELS: RACE, RESISTANCE, AND REMEMBRANCE IN THE FREE STATE OF WINSTON BY SUSAN NEELLY DEILY-SWEARINGEN B.A., Brandeis University M.A., Brown University M.A., University of New Hampshire DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History May 2019 This dissertation has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in History by: Dissertation Director, J. William Harris, Professor of History Jason Sokol, Professor of History Cynthia Van Zandt, Associate Professor of History and History Graduate Program Director Gregory McMahon, Professor of Classics Victoria E. Bynum, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History, Texas State University, San Marcos On April 18, 2019 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

SEQUOYA.Ii Constitu'tional Conveifflon 11

THE SEQUOYA.Ii CONSTITu'TIONAL CONVEifflON 11 THE SEQUOYAH CONSTITUTI OKAL CONVE?lTI ON AMOS DeZELL MAX'wELL,, Bachelor or Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College Stillwater, Ok1ahana 191+8 Submitted to the Department of History Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College In Part1a1 Fu:l.f'illment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF AR!S 195'0 111 OKLAHOMA '8BICULTUltAL & MlCHANICAL COLLE&I LIBRARY APR 241950 APPROVED Bia ) 250898 iv PREl'.lCE the Sequoy-ah Constitutional. Convention was held 1n Husk-0gee, Indian ferri to17, 1n. the aUBDller of 1905. It was the culminating event of a seriea ot eol.orrul occasions in the history or the .Five Civllized. Tribes. It was there that the deseendanta of those who made the trek west seventy-:f'ive years earlier sat with white men to vr1 te a eharter tor a new state.. They wrote a con st1tution, but it was never used as a charter tor a State or Sequo,yah. This work, which is primarily a stud,y or that convention and tbe reasons for its being called and its results, was undertaken at the suggestion of..,- father, Harold K. Max.well, in August, 1948. It has been carried to a conclusion through the a.id of a number o! persons, chief' among them being my wife, Betty Jo Max well. The need tor this study is a paramount one. Other than copies of the )(Q§koga f!l91P1J, the.re are no known records or the convention. Because much of the proceedings were in one or more Indian tongues there are some gaps in the study other than those due to the laek ot records,. -

The Trail of Tears and the Forced Relocation of the Cherokee Nation

National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior The Trail of Tears and the Forced Relocation of the Cherokee Nation The Trail of Tears and the Forced Relocation of the Cherokee Nation (Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Benjamin Nance, photographer) The caravan was ready to move out. The wagons were lined up. The mood was somber. One who was there reported that "there was a silence and stillness of the voice that betrayed the sadness of the heart." Behind them the makeshift camp where some had spent three months of a Tennessee summer was already ablaze. There was no going back. A white-haired old man, Chief Going Snake, led the way on his pony, followed by a group of young men on horseback. Just as the wagons moved off along the narrow roadway, they heard a sound. Although the day was bright, there was a black thundercloud in the west. The thunder died away and the wagons continued their long journey westward toward the setting sun. Many who heard the thunder thought it was an omen of more trouble to come.¹ This is the story of the removal of the Cherokee Nation from its ancestral homeland in parts of North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama to land set aside for American Indians in what is now the state of Oklahoma. Some 100,000 American Indians forcibly removed from what is now the eastern United States to what was called Indian Territory included members of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole tribes. The Cherokee's journey by water and land was over a thousand miles long, during which many Cherokees were to die. -

Trailword.Pdf

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. _X___ New Submission ____ Amended Submission ======================================================================================================= A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ======================================================================================================= Historic and Historical Archaeological Resources of the Cherokee Trail of Tears ======================================================================================================= B. Associated Historic Contexts ======================================================================================================= (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) See Continuation Sheet ======================================================================================================= C. Form Prepared by ======================================================================================================= -

Prince William Reliquary

April 2008 Vol. 7, No. 2 Prince William Reliquary RELIC, Bull Run Regional Library, Manassas, Virginia REL-I-QUAR-Y: (noun) A receptacle for keeping or displaying relics. THE 1901 MAP OF PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY, VIRGINIA AND ITS MAKERS: WILLIAM H. BROWN AND WILLIAM N. BROWN By the RELIC Staff The Brown Map of 1901 is very important for Prince William County historical research. It was the first detailed map of the area produced since the Civil War. It shows the home locations and names of people who were living in rural areas of the county and also identifies roads, streams, schools, mills and churches. It has two inset maps of the battlefields of Manassas and the dividing line between Hamilton and Dettingen parishes. There are also tables of property valuations and population. This map, printed in several colors, states it was made by William H. Brown, of Gainesville, Virginia. RELIC owns a monochromatic version of the map, which may be the original master. It is currently being conserved thanks to a donation from the Prince William County Historical Commission. A copy of the published map can be seen at The Library of Congress website.1 RELIC also has a black and white reproduction of the map printed and sold by the County’s Mapping Office. Cadet William N. Brown, VMI, Class of 1893. A question was recently Courtesy of Virginia Military Institute Archives. IN THIS ISSUE presented to RELIC -- who was William H. Brown, the mapmaker? In 1901 Map of Prince William 1900 there were at least three men living in Prince William County named County, Virginia and its “William H. -

Seth Eastman, a Portfolio of North American Indians Desperately Needed for Repairs

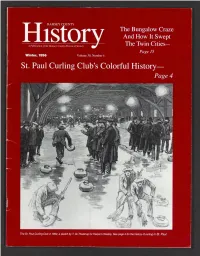

RAMSEY COUNTY The Bungalow Craze And How It Swept A Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society The Twin Cities— Page 15 Winter, 1996 Volume 30, Number 4 St. Paul Curling Club’s Colorful History The St. Paul Curling Club in 1892, a sketch by T. de Thulstrup for Harper’s Weekly. See page 4 for the history of curling in S t Paul. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Famham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz WARREN SCHABER 1 9 3 3 - 1 9 9 5 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Ramsey County Historical Society lost a BOARD OF DIRECTORS good friend when Ramsey County Commis Joanne A. Englund sioner Warren Schaber died last October Chairman of the Board at the age of sixty-two. John M. Lindley CONTENTS The Society came President to know him well Laurie Zehner 3 Letters during the twenty First Vice President years he served on Judge Margaret M. Mairinan the Board of Ramsey Second Vice President 4 Bonspiels, Skips, Rinks, Brooms, and Heavy Ice County Commission Richard A. Wilhoit St. Paul Curling Club and Its Century-old History Secretary ers. We were warmed by his steady support James Russell Jane McClure Treasurer of the Society and its work. Arthur Baumeister, Jr., Alexandra Bjorklund, 15 The Bungalows of the Twin Cities, With a Look Mary Bigelow McMillan, Andrew Boss, A thoughtful Warren We remember the Thomas Boyd, Mark Eisenschenk, Howard At the Craze that Created Them in St. Paul Schaber at his first County big things: the long Guthmann, John Harens, Marshall Hatfield, Board meeting, January 6, series of badly- Liz Johnson, George Mairs, III, Mary Bigelow Brian McMahon 1975. -

1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design Art, Art History and Design, School of 2011 Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida Kimberly Minor University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Art and Design Commons Minor, Kimberly, "Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida" (2011). Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-34 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida By Kimberly Minor Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History Under the Supervision of Professor Wendy Katz Lincoln, Nebraska April 2011 Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-34 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida Kimberly Minor, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Wendy Katz The first documented Native American art on paper includes the following drawings at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska: In the Winter, 1833-1834 (two versions) by Sih-Chida (Yellow Feather) and Mato-Tope Battling a Cheyenne Chief with a Hatchet (1834) by Mato-Tope (Four Bears) as well as an untitled drawing not previously attributed to the latter. -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing.