Downloads/Exec Md 20110210 Ss-Spouse-Instructions-To-Facilities.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate: Kentucky: Leans Republican Mcconnell (R-Inc) Vs

A M i n u t e - by- Minute Analysis of Which Races To Watch and Why You Should Watch Them By Arjun Jaikumar (brownsox) 6:00 EST Presidential: 1 Safe McCain: Kentucky (8) 1 Toss Up: Indiana (11) Senate: Kentucky: Leans Republican McConnell (R-inc) vs. Lunsford (D) Governor: Indiana: Likely Republican Daniels (R-inc) vs. Long Thompson (D) House: KY-02: Leans Republican Guthrie (R-open) vs. Boswell (D) KY-03: Likely Democratic Northup (R) vs. Yarmuth (D-inc) IN-03: Lean Republican Souder (R-inc) vs. Montagano (D) IN-09: Lean Democratic Sodrel (R) vs. Hill (D-inc) Polls close in Kentucky and Indiana in the eastern parts of the state at 6 EST. Polls in the CST part of the states reportedly will not close until 7:00 EST. Nevertheless, some of the earliest returns will come in from Kentucky and Indiana, so here’s how to read them as a barometer for the election. Presidential - Indiana The presidential contest has not been especially close here for several elections. The last time Indiana was too close to call when polls closed was during Bill Clinton’s 370-electoral-vote landslide in 1992. Even then, Clinton wound up losing the state by a significant margin. If Indiana is announced too close to call when polls close this year, it will be an indicator that Barack Obama is headed for a similar landslide victory himself, even if he isn’t quite able to carry the state. If Obama wins Indiana, you can start popping the champagne corks. While it doesn’t get him to 270 (when added to the Kerry states), it puts him just seven short, and victory in any one of Iowa, Virginia, North Carolina, Florida, Ohio, Colorado, Missouri (or in both Nevada and New Mexico) would win the election for him. -

2001 Fiscal Facts

2001 FI$CAL FACT$ VERMONT LEGISLATIVE JOINT FISCAL OFFICE Joint Fiscal Committee 2001 - 2002 Legislative Session Senator Susan Bartlett Senator Robert Ide Senator Cheryl Rivers Senator Richard Sears Senator Peter Shumlin Representative Richard Marron Representative Frank Mazur Representative Gaye Symington Representative Richard Westman Representative Mark Young Staff Stephen Klein, Chief Fiscal Officer Douglas Williams, Deputy Fiscal Officer Maria Belliveau, Associate Fiscal Officer Stephanie Barrett, Fiscal Analyst Chris Cole, Fiscal Analyst Steven Kappel, Fiscal Analyst Mark Perrault, Fiscal Analyst Sara Teachout, Fiscal Analyst Virginia Catone, Staff Assistant (session) Sandra Noyes, Data Manager/Office Administrator Rebecca Buck, Staff Associate/Personnel Officer 1 Baldwin Street Montpelier, Vermont 05633-5701 Phone: 802-828-2295 Fax: 802-828-2483 Internet: http://www.leg.state.vt.us/jfo Table of Contents PART I: AN OVERVIEW OF STATE FINANCES...................................................1 Total State Budget: Fiscal Year 2001......................................................................1 REVENUE......................................................................................................................2 State Revenue Forecast by Fund Type & Source: FY 2001.....................................3 General Fund Forecast............................................................................................4 Transportation Fund Forecast.................................................................................5 -

TETF 40,000 Recommendations 30,000 Current Funding 20,000 10,000 0 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Thermal Efficiency Task Force Analysis and Recommendations A Report to the Vermont General Assembly Meeting the Thermal Efficiency Goals for Vermont Buildings January 2013 Thermal Efficiency Task Force Members Debra Baslow, VT Bldgs & General Services Dept. Emily Levin, Efficiency Vermont Joseph Bergeron, Association of VT Credit Unions Sandra Levine, Conservation Law Foundation Kathy Beyer, Housing Vermont John Lincoln, Burlington Electric Dept. Ludy Biddle, NeighborWorks of Western VT Stu McGowan, private property owner Paul Biebel, Biebel Builders Jim Merriam, Efficiency Vermont Andrew Boutin, Pellergy LLC Elizabeth Miller, VT Public Service Dept. Allan Bullis, Common Sense Energy Johanna Miller, VT Natural Resources Council Chris Burns, Burlington Electric Dept. Wayne Nelson, LN Consulting Scott Campbell, CVCAC Craig Peltier, VT Housing & Conservation Board Tom Candon, VT Dept. of Financial Regulation Andrew Perchlik, VT Public Service Dept. Phil Cecchini, CVCAC Jay Pilliod, Efficiency Vermont Diana Chace, Conservation Law Foundation TJ Poor, VT Public Service Dept. Andrea Colnes, Energy Action Network John Quinney, Energy Co‐op of Vermont Matt Cota, Vermont Fuel Dealers Association Ajith Rao, Regulatory Assistance Project Neil Curtis, Efficiency Vermont Chuck Reiss, Reiss Building and Renovation Edward Delhagen, VT Public Service Dept. Bill Root, GWR Engineering Chris D'Elia, VT Bankers Association, Inc. Harald Schmidtke, SEVCA Norm Etkind, School Energy Management Program Gus Seelig, VT Housing & Conservation Board Richard Faesy, Energy Futures Group Andy Shapiro, Energy Balance Brian Fisher, Vermont Gas Eileen Simollardes, Vermont Gas Jeff Forward, Forward Consultants Gabrielle Stebbins, Renewable Energy Vermont Scott Gardner, Building Energy Gaye Symington, High Meadows Fund Chris Granda, Grasteu Assoc. / One Change Tom Thacker, BROC Malcolm Gray, Montpelier Construction, LLC George Twigg, Efficiency Vermont Bret Hamilton, Shelter Analytics, LLC Matthew Walker, VT Public Service Dept. -

Democratic Constitutionalism and the Marriage Revolution

ARTICLES STAGES OF CONSTITUTIONAL GRIEF: DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTIONALISM AND THE MARRIAGE REVOLUTION Anthony Michael Kreis* ABSTRACT Do courts matter? Historically, many social movements have turned to the courts to help achieve sweeping social change. Because judicial institutions are supposed to be above the political fray, they are sometimes believed to be immune from ordinary political pressures that otherwise slow down progress. Substantial scholarship casts doubt on this ro- manticized ideal of courts. This Article posits a new, interactive theory of courts and social movements, under which judicial institutions can legitimize and fuel social movements, but outside actors are necessary to enhance the courts’ social reform efficacy. Under this theory, courts matter and can be agents of social change by educating the public and dislodging institutional inertia in the political branches. This Article addresses these competing visions of judicial capacity for social change in the context of the struggle for marriage equality. Specifically, it considers the extent to which courts were responsible for Americans warming to LGBT rights and coming to new understandings of family, examining evidence marshaled from court rulings, polling data, interviews with federal and state judges, interviews with state elected officials, legislative histories, and media accounts. The Article concludes that courts played a vital role in fueling the marriage equality revolu- tion. They were not, however, unbridled agents of social change because external forces were necessary to maximize the impact of courts’ actions. * Visiting Assistant Professor of Law, Chicago-Kent College of Law. Ph.D., University of Georgia, J.D., Washington and Lee University, B.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

Table of Contents

ADVANCING VERMONT’S CREATIVE ECONOMY Celebrating Models of Community Success The Vermont Council on Rural Development Annual Conference Vermont State House—July 18, 2007 Conference Report Table of Contents Executive Summary...................................................................................... 1 Priority Recommendations .......................................................................... 4 Panel Discussion............................................................................................ 7 Featured Speaker Comments Bruce Hyde........................................................................................... 9 Lt. Gov. Brian Dubie............................................................................ 9 Gaye Symington ................................................................................. 13 Bill Schubart....................................................................................... 16 Working Group Reports Advancing Agricultural Innovation.................................................... 22 Building a Creative Economy Region................................................ 26 Developing Arts and Community Facilities....................................... 29 Developing Downtown Activity and Accessibility............................ 35 Expanding Partnerships between Cultural Organizations.................. 40 Incubating Creative New Businesses ................................................. 44 Marketing the Creative Economy...................................................... -

6-4 N&N Jan-Feb 2009

WTxDHAM Nsws e.NorES VolumeVI- Issue4 January,/ February 2009 f*,'*f,::tTf,*t*t*f*f;ff;ff*f;:f*',';rf*f;3f;ff*f*!';:f*?';:f;:!';ff;If;3f,Tf*f*f*f*f,*f;:f* l'P" l,q I;I Happy New Year, Windhaml y;i f*?'*?'*f*f,*f*i'*f*!'*f,*f*f*f*f*f*!'*t*f*f*",'*f*!'*?'*f*i'*f*i',::f*?'*?'*!'*?'*?',*f* Tuesday, March 3 2009, is Town Meeting Day ByEitithserke It's not too early to think of Town Meeting Day, which is always the first Tuesday in March, this year on March 3. There are cer- tain deadlines which should be kept in mind: At least 40 days before Town Meeting, i.e. no Iater than January 22,2009, all petitions for al Article to be voted on, must be filed at the Town Office. Wednesday, February 25,2009, is the last day to sign up for the voter check list if you are a new voter in Windham. The Leland and Gray High School Budget will be voted on at the Town Office 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. on February 4,2009. You should receive the 2008 Town Report about a week before the Town Meeting. You are urged to read it carefulty as it will contain all financial reports for 2008 and proposed budgets for 2009. Bring it with you to the Town Meeting. We will also at- tempt to get the March/April issue of Windham News and Notes to you with all the latest details by the last week in February. -

The Politics of Non-Incremental School Finance Reform: a Case Study Analysis of Vermont’S Act 60 As a Test of Mazzoni’S Arena Model

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE POLITICS OF NON-INCREMENTAL SCHOOL FINANCE REFORM: A CASE STUDY ANALYSIS OF VERMONT’S ACT 60 AS A TEST OF MAZZONI’S ARENA MODEL Kimberly Anne Curtis, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Dissertation Directed by: Professor Betty Malen Department of Education Policy Studies This research, grounded in political theory, had two major purposes: 1) to explain a case of non-incremental policy change within the realm of school finance reform; and 2) to test the utility of Mazzoni’s (1991) arena model for explaining state-level school finance policymaking. These goals were accomplished through an examination of the Vermont state legislature’s policymaking process in response to the Vermont Supreme Court Brigham v. State (1997) ruling declaring the state’s system of school finance unconstitutional. This analysis sought to explain how key political actors, taking advantage of favorable reform conditions, utilized power derived from positional authority as well as personal influence to impact the passage of Act 60, an innovative and forcefully redistributive piece of school finance legislation. The research employed a qualitative case method as a means to answer the research questions. Data collection drew from an informant interview process supported by extensive primary and secondary source document review. Data were systematically analyzed against the conceptual framework, presented in a case narrative and discussed in light of related literature to generate analytic conclusions with regard to the process of state education policymaking for school finance. Study findings highlight the general utility of Mazzoni’s arena model in explaining non-incremental policy change in the realm of school finance reform; the importance of politically savvy and well-situated policy entrepreneurs who can take advantage of propitious events such as a court ruling to advance non-incremental policy reform; and the role of political elites in advancing the cause of school finance reform. -

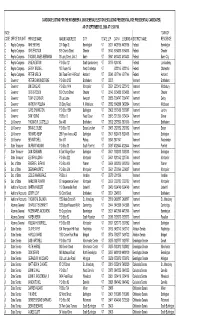

Annual Report 2013 Energy Action Network Participants All Lists Current As of 1/14

Annual Report 2013 Energy Action Network Participants all lists current as of 1/14 MEMBERS Peter Adamczyk Vermont Energy Investment Corporation Laurie Fielder Vermont State Employees Credit Union Charles Baker Chittenden County Regional Planning Committee Sara Gilbert NeighborWorks of Western Vermont Robert Barton Catalyst Financial Karen Glitman Vermont Energy Investment Corporation Amanda Beraldi Green Mountain Power Steve Greenfield Vermont Economic Development Authority Arthur Berndt Maverick Lloyd Foundation Robert Griffin Green Mountain Power Anne Berndt Maverick Lloyd Foundation John Hollar City of Montpelier Janet Besser New England Clean Energy Council Karen Horn Vermont League of Cities and Towns Ludy Biddle NeighborWorks of Western Vermont Scott Johnstone Vermont Energy Investment Corporation Kathryn Blume Vermontivate Dan Jones Montpelier Energy Advisory Committee Peter Bourne Bourne's Energy Ellen Kahler Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund Lee Bouyea Fresh Tracks Capital Emily Levin Vermont Energy Investment Corporation Melody Burkins University of Vermont Julie Lineberger LineSync Architecture Laurie Burnham Sandia National Laboratory Paul Markowitz Vermont Energy Investment Corporation Paul Burns Vermont Public Interest Research Group Linda McGinnis Independent Policy Analyst/Economist Megan Camp Shelburne Farms Carrie McLaughlin Erin Carroll Vermont Energy Investment Corporation Ralph Meima Brattleboro Energy Committee Joseph Cincotta LineSync Architecture Jim Merriam Efficiency Vermont Hal Cohen Central Vermont Community Action Council -

Journal of the Joint Assembly of the State of Vermont Biennial Session, 2009 ______In Joint Assembly, January 8, 2009 10:00 A.M

Journal of the JOINT ASSEMBLY Biennial Session 2009 JOURNAL OF THE JOINT ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF VERMONT BIENNIAL SESSION, 2009 ________________ IN JOINT ASSEMBLY, JANUARY 8, 2009 10:00 A.M. The Senate and the House of Representatives met in the Hall of the House of Representatives pursuant to a Joint Resolution which was read by the Clerk and is as follows: J.R.S. 2. Joint resolution to provide for a Joint Assembly to receive the report of the committee appointed to canvass votes for state officers. Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives: That the two Houses meet in Joint Assembly on Thursday, January 8, 2009, at ten o'clock in the forenoon to receive the report of the Joint Canvassing Committee appointed to canvass votes for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, State Treasurer, Secretary of State, Auditor of Accounts and Attorney General, and if it shall be declared by said Committee that there had been no election by the freemen of any of said state officers, then to proceed forthwith to elect such officers as have not been elected by the freemen. Presiding Officer Honorable Brian E. Dubie, President of the Senate, in the Chair. Clerk David A. Gibson, Secretary of the Senate, Clerk. Report of the Joint Canvassing Committee Senator White, Co-Chair, then presented the report of the Joint Canvassing Committee, which was as follows: The Joint Canvassing Committee appointed to canvass the votes for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, State Treasurer, Secretary of State, Auditor of Accounts, and Attorney General respectfully reports: That having been duly sworn, it has attended to the duties of its trust and finds the number of votes to have been: 2337 2338 JOURNAL OF THE JOINT ASSEMBLY For GOVERNOR...................................................................319,085 Necessary to have a major part of the votes .....................159,543 Peter Diamondstone, Liberty Union ................................1,710 James H. -

CAN-Did Winter 2008

WINTER 2008 www.nukebusters.org The CAN-Did Press THE NEWSLE tt ER OF T HE CI T IZE N S AW A RE N ESS NE T WORK ACT TODAY TO CHANGE TOMORROW... Nuclear Free Jubilee Takes Over Brattleboro The largest no-nukes/pro-green demonstration the tri-state region has ever seen filled the streets and Town Common in Brattle- boro on Saturday, October 25th. Organized by “Safe & Green,” a still less than one-year-old campaign working in coaliton with CAN, Nuclear Free Vermont, and the New England Coalition, the Jubilee began with a spirited parade led by the famed Bread & Puppet Theater. Featuring two street bands, colorful banners from a dozen local towns (e.g., “Colrain, MA Says Solar Yes! Nukes No!”), and a sea of the Theater’s trademark giant puppets (assembled and rehearsed the evening before with the help of over fifty volunteers), the parade snaked its way up Main Street from one end of downtown Brattleboro to the other, with smiles and cheers from bystanders all along the way. With an estimated 500 people crowded around him on the Town Common, Bread & Puppet founder Peter Schuman led a haunting but ultimately triumphant performance of his “Resurrec- tion Mass” in which the “bad idea” of generating electricity from splitting atoms was finally buried in the ground forever. This was “Reverend Billy” of the “Church of Stop Shopping.” Among the followed by a two-hour rally of rousing speeches, spirited music, featured musicians were nationally renowned folksinger Charlie and a “Green Energy Fair” comprised of energy conservation and King, the Brattleboro area’s own MacArthur Family string band, renewable energy exhibits. -

Vtdigger 2015 Annual Report

2015 Annual Report Celebrating Six Years of Investigative Journalism in Vermont 5,813 ARTICLES 33,966 COMMENTS 6,083,263 PAGE VIEWS 132,055 MONTHLY READERS Vermont’s Online Nonprofit News Daily WHO WE ARE VTDigger is a nonprofit online news daily dedicated to public-service journalism. We cover Vermont politics, consumer affairs, business, education, energy, the environment and other matters of public concern. VTDigger was founded in 2009 and merged with the Vermont Journalism Trust in 2011, becoming a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. The mission of Vermont Journalism Trust and VTDigger is to produce rigorous journalism that explains complex issues, holds the government accountable to the public, and engages Vermonters in the democratic process. 2015 Board of Directors 2015 Staff and Interns Kevin Ellis, East Montpelier Executive Director & Editor: Anne Galloway Anne Galloway, East Hardwick Publisher: Diane Zeigler Don Hooper, Brookfield Associate Publisher: Phayvanh Luekhamhan Curtis Ingham Koren, Brookfield Director of Underwriting: Theresa Murray-Clasen Crea Lintilhac, Shelburne Assignment Editor: Tom Brown Neale Lunderville, Burlington Senior Editor and Reporter: Mark Johnson David Mindich, Burlington Copy Editor: Cate Chant Lauren Moye, Montpelier Reporters: Jasper Craven, Mike Faher, John Carol Ode, Burlington Herrick, Elizabeth Hewitt, Laura Krantz, Erin Bill Porter, Adamant Mansfield, Amy Ash Nixon, Tiffany Danitz Pache, Carin Pratt, Strafford Mike Polhamus, Morgan True, Jess Wisloski Mathew Rubin, Montpelier Interns: Flynn Aldrich, George Aldrich, Laura Bill Schubart, Hinesburg Greshin, Sam Heller, Emma Murphy, Clare Neal, Ina Smith Johnson, Poultney Sarah Olsen, Nell Sather, Phoebe Sheehan, Frances Stoddard, Williston Kayla Woodman Stephen Terry, Middlebury General Information Mailing Address: Press Releases & Membership Support: 97 State Street Commentaries: The membership support we Montpelier, Vermont 05602 We invite you to send us press receive from our readers is what TEL: 802.225.6224 releases and commentaries to makes our work possible. -

Race Code Office Sought Printed Name Mailing

CANDIDATE LISTING FOR THE NOVEMBER 4, 2008 GENERAL ELECTION (EXCLUDING PRESIDENTIAL/VICE PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES) AS OF SEPTEMBER 22, 2008 AT 12:30 P.M. RACE TOWN OF CODE OFFICE SOUGHT PRINTED NAME MAILING ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP DAY # EVENING # DISTRICT NAME RESIDENCE C Rep to Congress MIKE BETHEL 201 Gage St Bennington VT 05201 4429196 4429196 Federal Bennington C Rep to Congress CRIS ERICSON 879 Church Street Chester VT 05143 8754038 8754038 Federal Chester C Rep to Congress THOMAS JAMES HERMANN 38 Long Street, Unit 3 Barre VT 05641 4614433 4614433 Federal Barre City C Rep to Congress JANE NEWTON P.O. Box 121 South Londonderry VT 05155 8244163 Federal Londonderry C Rep to Congress JERRY TRUDELL 187 Route 105 West Charleston VT 9222145 9222145 Federal Charleston C Rep to Congress PETER WELCH 346 Town Farm Hill Road Hartland VT 05048 6517144 6517144 Federal Hartland D Governor PETER DIAMONDSTONE P.O. Box 2155 Brattleboro VT 05303 Vermont Brattleboro D Governor JIM DOUGLAS P.O. Box 1414 Montpelier VT 05601 2233412 2233412 Vermont Middlebury D Governor CRIS ERICSON 879 Church Street Chester VT 05143 8754038 8754038 Vermont Chester D Governor TONY O'CONNOR 93 Leo Lane Newport VT 05855 7664747 7664747 Vermont Derby D Governor ANTHONY POLLINA 93 Story Road N. Middlesex VT 05682 8642008 3432604 Vermont Middlesex D Governor GAYE SYMINGTON P.O. Box 1584 Burlington VT 05402 6513488 3633907 Vermont Jericho D Governor SAM YOUNG PO Box 10 West Glover VT 05875 3210365 6734334 Vermont Glover E Lt. Governor THOMAS W. COSTELLO Box 483 Brattleboro VT 05302 2575533 3801616 Vermont Brattleboro E Lt.