PALERMO 1140 Chants from the Normans in Sicily This Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 27, 2018 RESTORATION of CAPPONI CHAPEL in CHURCH of SANTA FELICITA in FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS to SUPPORT FROM

Media Contact: For additional information, Libby Mark or Heather Meltzer at Bow Bridge Communications, LLC, New York City; +1 347-460-5566; [email protected]. March 27, 2018 RESTORATION OF CAPPONI CHAPEL IN CHURCH OF SANTA FELICITA IN FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS TO SUPPORT FROM FRIENDS OF FLORENCE Yearlong project celebrated with the reopening of the Renaissance architectural masterpiece on March 28, 2018: press conference 10:30 am and public event 6:00 pm Washington, DC....Friends of Florence celebrates the completion of a comprehensive restoration of the Capponi Chapel in the 16th-century church Santa Felicita on March 28, 2018. The restoration project, initiated in March 2017, included all the artworks and decorative elements in the Chapel, including Jacopo Pontormo's majestic altarpiece, a large-scale painting depicting the Deposition from the Cross (1525‒28). Enabled by a major donation to Friends of Florence from Kathe and John Dyson of New York, the project was approved by the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Firenze, Pistoia, e Prato, entrusted to the restorer Daniele Rossi, and monitored by Daniele Rapino, the Pontormo’s Deposition after restoration. Soprintendenza officer responsible for the Santo Spirito neighborhood. The Capponi Chapel was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi for the Barbadori family around 1422. Lodovico di Gino Capponi, a nobleman and wealthy banker, purchased the chapel in 1525 to serve as his family’s mausoleum. In 1526, Capponi commissioned Capponi Chapel, Church of St. Felicita Pontormo to decorate it. Pontormo is considered one of the most before restoration. innovative and original figures of the first half of the 16th century and the Chapel one of his greatest masterpieces. -

Chapter 11 Painting

Chapter 11 Painting • Medium: material that pigments are suspended in • Binder: holds the particles together (glue) • Support: in painting what the artist paints on • Transparent: paint that can be seen through • Opaque: paint that cannot be seen through • Ground: primer used to even the surface of the support, even application • Solvent: thinner that allows for paint to flow easier 1. Painting as the ability to copy during the Middle Ages 2. La Pittura: personification of Painting 1. Why is this important? Title: The Art of Painting Source/Museum: Vault of the Main Room, Arezzo, Casa Vasari. Canali Photobank, Capriolo, Italy. Artist: Giorgio Vasari Medium: Fresco Date: 1542 Size: n/a La Pintura 1. Representation 1. Herself 2. La Pittura 1. Why this representation? 2. Pendent: symbol of imitation 3. Accurate representation 1. Representation of nature through artist eyes 4. Portrayal 1. Real women 2. Idealized personification 5. Copy work or creative? 6. Equal to Leonardo and Michelangelo? 7. Western Painting: Painting the Nature 1. Zeuxius Vs. Parrhasius 1. Zeuxius: paints grapes and birds come down to eat them 2. Parrhasius: paints a curatian and Zeuxius asks him to remove the curtain so he can see the painting Title: Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting Source/Museum: The Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Artist: Artemisia Gentileschi Medium: Oil on canvas Date: 1630 Size: 35 ¼ x 29 in. Encaustic Encaustic Encaustic 1. Combining pigment with binder of hot wax 2. Funerary portraiture from Faiyum 60 miles South of Cairo 3. Real person 1. Naturalistic sensitive depiction of the face Source/Museum: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. -

The Secrets of Fresco Painting in the Italian Renaissance Art 2

1 ...the secrets of fresco painting in the Italian Renaissance Art 2 A PROJECT FOR A UNIQUE EXHIBITION The Renaissance greatest masters : Giotto, Beato Angelico, Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raffaello, Leonardo..... are brought together in this special exhibition by a leading thread : the art of fresco painting. In the spotlight of the exhibition are the unique frescoes created in Antonio De Vito’s Florentine atelier, telling us the intriguing and spectacular story of the art of the fresco. De Vito's own interpretations of the works of these immense artists guide us to the discovery of their secrets. The exhibition offers a path that leads visitors to the discovery not only of the technical aspects of fresco painting, but also of the artistic concepts characteristic of the Renaissance. The uniqueness of this project lies in the fact that it presents real frescoes, detached from the walls with a special technique, giving the visitors the opportunity to see works that traditionally can be admired only on the spot where they were painted. 3 THE EXHIBITION Our project provides a variable number of fresco paintings depending on the available space. Preparatory cartoons and sketches will be displayed with some of the works. Each fresco is displayed with caption and photographs. The initial section displays a rich gallery of frescoes, supported by an introduction to the technique of fresco painting with texts, photographs and videos to illustrate the differents steps in painting. Besides the gallery, in a unique development, a second section offers an area set up full of various features recreating the atelier of a Renaissance painter. -

Voyage from Palermo to Venice

VOYAGE FROM PALERMO TO VENICE Exploring the Historic Cities and Art Treasures of the Ionian & Adriatic Seas Aboard the 24-cabin Yacht Elysium With archaeologist Ivancica Schrunk May 21 – 31, 2022 Dear Traveler, Archaeological Institute of America ˆ ˆ Next spring, we invite you to join AIA lecturer and host Ivancica (Vanca) Schrunk LECTURER AND HOST aboard the private, yacht-like Elysium on a purpose-designed voyage from Sicily to Venice by way of Montenegro and Croatia, discovering historical gems of the Mediterranean, Ionian, and Adriatic Seas. The combination of fascinating history and sublime beauty is what makes these shorelines among the most spectacular places in the world. Consider Sicily’s Taormina, whose ancient Greek theater gazes at massive Mount Etna; the remarkable trulli villages of Italy’s Puglia region; the old, picturesque town of Kotor, nested at the head of a long, scenic bay; the beautifully preserved medieval city of Dubrovnik, overlooking the sparkling waters of the Adriatic; Split’s enormous Palace of Diocletian, one of the finest Roman monuments to survive from antiquity; the small town of Porec in Croatia’s Istria, home to the 6th-century Basilica of Euphrasius with its gleaming Byzantine mosaics; and Venice, our last stop and unquestionably one of the world’s most stunning and influential cities. Born in Zagreb, Croatia, AIA lecturer and host Vancǎ Schrunk will enrich your travel experience and understanding of the ancient and medieval history of this region through an onboard series of stimulating lectures as well as informal discussions. In addition, excellent local guides will accompany you on excursions throughout ˆ the program. -

Kayla Sprague Catalog Essay the Triumph of Death in Palermo the Triumph of Death Is a Grand Fresco That Was Commissioned For

Kayla Sprague Catalog Essay The Triumph of Death in Palermo The Triumph of Death is a grand fresco that was commissioned for the Sclafani Plazza in 1446. There is little information on the artist and the patron. The Triumph of Death in Palermo was painted in the late Gothic style, a century after the Black Death. It became a popular artistic theme across Europe during the 14th and 15th century and was a successful tool in terrifying people about the plague. The Triumph of Death was commonly recognized in that no description or text were necessary. 1 Unlike previous medieval paintings, the “Triumph” paintings did not inspire faith, however, the graphic images were instead used with intent to redirect panic from the plague and subtly scare people into paying attention to religion.2 The paintings were commissioned for hospitals and cemeteries and served as a warning that the alive were being judged by the dead; people should be careful not to sin for they would suffer as a result of the plague. The belief of the cause of the plague impacted what artists depicted in their paintings and gradually affected future iconography. The scene depicted in The Triumph of Death in Palermo, which can be analyzed in 6 parts, is located in a garden surrounded by a hedge, with groups of people cluttering the edges of the painting. In the center, a skeleton, personifying “Death” and riding an emaciated horse, interrupts the scene, carrying a scythe and shooting arrows from a bow. At the top left a man walks two dogs on taut leashes, one of the dogs appearing disturbed and growling and the other sniffing the hedge. -

Design and Renovation Guidelines and Protocols

GUIDELINES and PROTOCOLS for the DESIGN and RENOVATION of CHURCHES and CHAPELS First Sunday of Advent December 1, 2013 Catholic Diocese of Saginaw Office of Liturgy The Office of Liturgy for the Diocese of Saginaw has prepared this set of guidelines and protocols to be used in conjunction with those outlined in Built of Living Stones. This diocesan document attempts to give clearer direction to those areas that Built of Living Stones leaves open to particular diocesan recommendations and directives. All those involved in any design for new construction or renovation project of a church or chapel in the Diocese of Saginaw should be familiar with these guidelines and protocols and ensure that their intent is incorporated into any proposed design. Guidelines and Protocols for the Design And Renovation of Churches and Chapels Text 2009, Diocese of Saginaw, Office of Liturgy. Latest Revision Date: December 1, 2013. Excerpts from Built of Living Stones: Art, Architecture, and Worship: Guidelines of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops copyright 2001, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington, DC. Used with permission. All rights reserved. Excerpts taken with permission and appreciation from similar publications from the following: Archdiocese of Chicago; Diocese of Grand Rapids; Diocese of Seattle; Archdiocese of Milwaukee; Diocese of Lexington; Archdiocese of Philadelphia and Diocese of La Crosse. No part of these works may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the copyright holder. Printed in the United States of America For you have made the whole world a temple of your glory, that your name might everywhere be extolled, yet you allow us to consecrate to you apt places for the divine mysteries. -

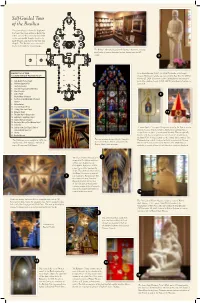

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13

Self-Guided Tour of the Basilica 13 This tour takes you from the baptismal 14 font near the main entrance, down the 12 center aisle to the sanctuary, then right to the east apsidal chapels, back to the 16 15 11 Lady Chapel, and then to the west side chapels. The Basilica museum may be 18 17 7 10 reached through the west transept. 9 The Bishops’ Museum, located in the Basilica’s basement, contains pontificalia of various American bishops, dating from the 19th century. 11 6 5 20 19 8 4 3 BASILICA OF THE Saint André Bessette, C.S.C. (1845-1937), founder of St. Joseph’s SACRED HEART FLOOR PLAN Oratory, Montréal, Canada, was canonized by Pope Benedict XVI on October 17, 2010. The statue of Saint André Bessette was designed 1. Font, Ambry, Paschal Candle by the Rev. Anthony Lauck, C.S.C. (1985). Saint André’s feast day is 2. Holtkamp Organ (1978) 8 January 6. 3. Sanctuary Crossing 2 4. Seal of the Congregation of Holy Cross 1 5. Altar of Sacrifice 6. Ambo (Pulpit) 9 7. Original Altar / Tabernacle 8. East Transept and World War I Memorial Entrance 9. Tintinnabulum 10. St. Joseph Chapel (Pietà) 11. St. Mary / Bro. André Chapel 2 12. Reliquary Chapel 17 13. The Lady Chapel / Baroque Altar 14. Holy Angels / Guadalupe Chapel 15. Mural of Our Lady of Lourdes 16. Our Lady of Victory / Basil Moreau Chapel 17. Ombrellino 18. Stations of the Cross Chapel / Tomb of A “minor basilica” is a special designation given by the Pope to certain John Cardinal O’Hara, C.S.C. -

Altars Personified: the Cult of the Saints and the Chapel System in Pope Pascal I's S. Prassede (817-819) Judson J

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Faculty Publications and Research Pomona Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2005 Altars personified: the cult of the saints and the chapel system in Pope Pascal I's S. Prassede (817-819) Judson J. Emerick Pomona College Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis Recommended Citation "Altars Personified: The ultC of the Saints and the Chapel System in Pope Pascal I's S. Prassede (817-819)" in Archaelogy in Architecture: Studies in Honor of Cecil L. Striker, ed. J. Emerick and D. Deliyannis (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 2005), pp. 43-63. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Faculty Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archaeology in Architecture: Studies in Honor of Cecil L. Striker Edited by Judson J. Em erick and Deborah M. Deliyannis VERLAG PHILIPP VON ZABERN . MAINZ AM RHEIN VII, 216 pages with 146 black and white illustrations and 19 color illustrations Published with the assistance of a grant from the James and Nan Farquhar History of An Fund at the University of Pennsylvania Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliotbek Die Deutsche Bibliorhek lists this publication in the Deutsche NationalbibJ iographie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at dJttp://dnb.ddb.de> . © 2005 by Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Maim am Rhein ISBN- I0: 3-8053-3492-3 ISBN- 13: 978-3-8053-3492-1 Design: Ragnar Schon, Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Maim All rights reserved. -

The Drawings of Girolamo Romanino. Part IT

Originalveroffentlichung in: Burlington Magazine 137, Mai 1995, S, 300-306 ALESSANDRO NOVA The drawings of Girolamo Romanino. Part IT 11. Pyramus and Thisbe, by Girolamo Romanino. Pen and brown ink, 14 by 16.6 cm. (Louvre, Paris). 3 PREPARATORY drawings by Romanino for surviving paint Palazzo Martinengo in the via delle Cossere in Brescia, a ings he executed during the last thirty years of his career are palace once owned by Leonardo III Martinengo delle Palle 1 not numerous, but some of his late sheets provide important who died in 1536. Panazza listed this cycle among Romani 1 evidence about various lost works. no's lost works, and all subsequent scholars have taken this to After completing his frescoes for Cardinal Clesio at Trent, be the case. Yet, while three of the lunettes have lost all trace Romanino returned to Brescia in 1532. It remains contro of their frescoes, one contains three barely visible heads, and versial exactly which paintings can be dated to the early the central lunette retains the image of a woman holding a 1530s, but it is possible that a drawing now in the Louvre stick with which she apparently threatens two unidentified 1 (Fig. 11) belongs to these years. The spirited style of this figures. It is impossible to establish whether any of these sketch in pen and brown ink is similar to that of the drawings lunettes did indeed contain a fresco of Pyramus and Thisbe, executed during his Trentine period, and the theme of Pyra but the surviving fragment was probably executed around mus and Thisbe - first identified by Creighton Gilbert — was 1532-34, a perfectly acceptable date for the drawing in the 6 often represented by early sixteenth-century German artists, Louvre. -

Ann O'hanlon's Kentucky Mural Harriet W

The Kentucky Review Volume 8 | Number 1 Article 4 Spring 1988 Ann O'Hanlon's Kentucky Mural Harriet W. Fowler University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Art and Design Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Fowler, Harriet W. (1988) "Ann O'Hanlon's Kentucky Mural," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ann O'Hanlon's Kentucky Mural Harriet W. Fowler Over fifty years after its creation, the University of Kentucky's Memorial Hall mural, a Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) fresco by Ann Rice O'Hanlon, remains virtually unchanged from the time it was painted. Its colors have not lost their jewel-like tonalities, and its multi-layered composition is still crisply delineated.1 Completed in 1934 for the PWAP, the mural represents a pictorial history of important central Kentucky events and landmarks. It admirably fulfills the directive of its New Deal sponsors to document "the American Scene," a task which O'Hanlon, a then-recent graduate of the university, adapted to the local scene as she also wove autobiographical and poetic elements into the rich narrative of central Kentucky history. -

Renaissance on the Beach” Epitomized by 16Th Century Fresco at Sale E Pepe®, Marco Island, Fla

“Renaissance on the beach” epitomized by 16th century fresco at Sale e Pepe®, Marco Island, Fla. MARCO ISLAND, Fla. (February 24, 2006) — At Sale e Pepe on Marco Island, Southwest Florida’s quintessentially authentic Italian restaurant, nothing evokes “renaissance on the beach” as well as the 12-foot high hand-painted replica of a 416-year old masterpiece by Jacopo Zucchi, artist in residence to the Medici court, chief assistant for Vatican decorations, and honored with preparing the funeral decorations for Michelangelo. Zucchi’s original fresco, located in the Palazzo Ruspoli in Rome, inspired contemporary artist Rossen Tonkov, commissioned by Sale e Pepe’s owners, because of its large scale and grandeur as well as its powerful symbolic imagery depicting the constant balance of church and state power, an eternal Italian theme. Aesthetically, the fresco’s colors and shapes complement the restaurant’s intricate mosaic floors, carved marble detailing, historic Italian tapestries and paintings, and 400-year-old antiques. The final affect is a vision of an ancient seaside Italian restaurant. Tonkov, a Bulgarian native, was struck by the beauty of the palette used in the interior design of Sale e Pepe—stones, fabrics and fine objects – and the golden travertine walls providing the backdrop to the masterpiece. The fresco depicts a regal and impressive woman, papal crown in one hand, and the crown of the emperor of Rome in the other, commanding the focal point of the restaurant and looking out over the grotto-like intimate dining alcoves that distinguish Sale e Pepe’s formal dining area. Rossen Tonkov especially appreciated that his chosen image adhered to his golden rule—that a piece of art provide a minimum of seven different views in order to enrich a space. -

Open Muroya Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY A COMPARISON OF NORMAN ARCHITECTURE IN THE KINGDOMS OF ENGLAND AND SICILY Mikito Muroya FALL 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in History with honors in History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kathryn Salzer Assistant Professor of History Thesis Supervisor Mike Milligan Senior Lecturer in History Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This study offers a comparison of the differing architectural styles and forms in the Norman Kingdoms of Sicily and England, exploring what exactly differed, as well as attempting to determine why such differences exist in each area. In the Kingdom of England, the Normans largely imported their own forms from Normandy, incorporating little of the Anglo-Saxon architectural heritage. There are in fact examples of seemingly deliberate attempts to eliminate important Anglo-Saxon buildings and replace them with structures built along Norman lines. By contrast, in the Kingdom of Sicily, buildings erected after the arrival of the Normans feature a mix of styles, incorporating features of the earlier Islamic, Byzantine and local Italian Romanesque, as well as the Normans' own forms. It is difficult to say why such variance existed, but there are numerous possibilities. Some result from the way each state was formed: England had already existed as a kingdom when the Normans conquered the land and replaced the ruling class, while the Kingdom of Sicily was a creation of the Norman conquerors; furthermore, the length of time taken to complete the conquest contrasted greatly.