The Place of the Sadducees in First-Century Judaism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetry of the Damascus Document

The Poetry of the Damascus Document by Mark Boyce Ph.D. University of Edinburgh 1988 For Carole. I hereby declare that the research undertaken in this thesis is the result of my own investigation and that it has been composed by myself. No part of it has been previously published in any other work. ýzýa Get Acknowledgements I should begin by thanking my financial benefactors without whom I would not have been able to produce this thesis - firstly Edinburgh University who initially awarded me a one year postgraduate scholarship, and secondly the British Academy who awarded me a further two full year's scholarship and in addition have covered my expenses for important study trips. I should like to thank the Geniza Unit of the Cambridge University Library who gave me access to the original Cairo Document fragments: T-S 10 K6 and T-S 16-311. On the academic side I must first and foremost acknowledge the great assistance and time given to me by my supervisor Prof. J. C.L. Gibson. In addition I would like to thank two other members of the Divinity Faculty, Dr. B.Capper who acted for a time as my second supervisor, and Dr. P.Hayman, who allowed me to consult him on several matters. I would also like to thank those scholars who have replied to my letters. Sa.. Finally I must acknowledge the use of the IM"IF-LinSual 10r package which is responsible for the interleaved pages of Hebrew, and I would also like to thank the Edinburgh Regional Computing Centre who have answered all my computing queries over the last three years and so helped in the word-processing of this thesis. -

The Concept of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate Faculty Publications and Presentations School 2010 The onceptC of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant Jintae Kim Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kim, Jintae, "The oncC ept of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant" (2010). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 374. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/374 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate School at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [JGRChJ 7 (2010) 98-111] THE CONCEPT OF ATONEMENT IN THE QUMRAN LITERatURE AND THE NEW COVENANT Jintae Kim Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, Lynchburg, VA Since their first discovery in 1947, the Qumran Scrolls have drawn tremendous scholarly attention. One of the centers of the early discussion was whether one could find clues to the origin of Christianity in the Qumran literature.1 Among the areas of discussion were the possible connections between the Qumran literature and the New Testament con- cept of atonement.2 No overall consensus has yet been reached among scholars concerning this issue. -

Pesher and Hypomnema

Pesher and Hypomnema Pieter B. Hartog - 978-90-04-35420-3 Downloaded from Brill.com12/17/2020 07:36:03PM via free access Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah Edited by George J. Brooke Associate Editors Eibert J.C. Tigchelaar Jonathan Ben-Dov Alison Schofield VOLUME 121 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/stdj Pieter B. Hartog - 978-90-04-35420-3 Downloaded from Brill.com12/17/2020 07:36:03PM via free access Pesher and Hypomnema A Comparison of Two Commentary Traditions from the Hellenistic-Roman Period By Pieter B. Hartog LEIDEN | BOSTON Pieter B. Hartog - 978-90-04-35420-3 Downloaded from Brill.com12/17/2020 07:36:03PM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hartog, Pieter B, author. Title: Pesher and hypomnema : a comparison of two commentary traditions from the Hellenistic-Roman period / by Pieter B. Hartog. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2017] | Series: Studies on the texts of the Desert of Judah ; volume 121 | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Ne Wtestamentandj Udai Sm of the Ne Wtestament Pe

NEW TESTAMENT AND JUDAISM OF THE NEW TESTAMENT PERIOD ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION: HILLEL’S SELF-AWARENESS AND JESUS by Professor David Flusser In memory of my dear friend and scholar, Ary eh Toeg, who fell in the Yom Kippur War Even today there exists in New Testament scholarship a trend which considers all references to a high self-awareness of Jesus as secondary ele- ments in the Gospels, contradicting Jesus’s own understanding of who he was: “He was”, in the words of Paul Winter, “a normal person - he was the norm of normality”.1 Not only does a careful analysis of the texts for- bid this assumption, but in addition it is no longer possible nowadays, af- ter the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, to affirm that a high self-esteem, both with regard to one’s personal and one’s religious standing, did not exist in Judaism of the Second Temple period . We have not only learned about the Essene Teacher of Righteousness, but we can now also study the author of the Thanksgiving Scroll, a man who considered himself the me- diator of divine mysteries. Thus the liberal conception of the absence of an elevated self-awareness in Jesus is today anyhow obsolete. Additional evidence for the occurrence of an exalted self-awareness in the Second Temple period is to be found in some sayings of Hillel the Pharisee,2 who died before Jesus was born. This is a surprising fact, as the Pharisees, the founders of rabbinic Judaism, were sometimes conceited as scholars, but we very seldom find that a Rabbi would imagine that he as a person had a special role to play in the meta-historical economy of the uni- verse. -

What Are They Saying About the Historical Jesus?

What are They Saying about the Historical Jesus? Craig A. Evans Acadia Divinity College INTRODUCTION These are exciting times for those who have learned interest in the Jesus of history. The publication of a significant number of Dead Sea Scrolls just over a decade ago, the publication in the last two decades or so of a host of related writings from or just before the New Testament period, and ongoing archaeological work in Israel, especially in and around Jerusalem and in Galilee, have called into question old conclusions and assumptions and opened the doors to new lines of investigation. It is not surprising that several academic and semi-academic books, published by leading presses, have enjoyed unprecedented sales and attention. Even major network television has produced documentaries and news programs, some of whom were viewed by record-setting audiences. A major factor in much of the new interest in Jesus has been the controversy generated by the Jesus Seminar, based in California and led by maverick New Testament scholar Robert Funk. Although it cannot be said that all of the views of Funk and his Seminar are accepted by mainstream scholarship, their provocative conclusions and success at grabbing headlines have caught the attention of the general public to a degree I suspect not many twenty years ago would have thought possible. Of course, scholars and popular writers have been publishing books on Jesus, in great numbers, for centuries. The difference is that now scholars are writing for the general public and the popular authors—at least some of them—are reading the scholars—at least selectively. -

Midrash and Pesher-Their Significance to T

Midrash and Pesher: Their Significance to the Intertextuality Debate By Dan Fabricatore INTRODUCTION The discovery of the Qumran scrolls has shed much light as to how the scholars of the 1st century viewed the Old Testament Scriptures. In these scrolls we find hermeneutical techniques common to that day that some hold may have influenced the New Testament authors as they themselves used Old Testament passages for their own purposes. This presentation will attempt to look at concepts of midrash and pesher, their use in the New Testament, and their relevance to New Testament study today. TERMINOLOGY Trying to define midrash and pesher is akin to a maze. Just when you think you have a handle on the thing, you are afforded several new ways in which to go.1 Midrash The term midrash is a Hebrew noun (midrāš; pl. midrāšîm) derived from the verb dāraš which means “to search” (i.e. for an answer). Therefore midrash means “inquiry,” “examination” or “commentary.”2 Ezra 7:10 is the first use where a written text is the object of dāraš. 10 For Ezra had set his heart to study the law of the LORD, and to practice it, and to teach His statutes and ordinances in Israel. 10 T#o(jlaw; hwFhy: trawTo-t)e $wrod;li wbobFl; 4ykihe )rFz;(e yKi S .+PF$;miW qxo l)erF#;yiB; dMelal;W Midrash has a variety of meanings and uses in the Qumran literature. It is used to refer to “judicial investigation, study of the law, and interpretation.”3 However the main use at Qumran 1 This first presentation is somewhat purposely vague. -

F.F. Bruce, "The Dead Sea Habakkuk Scroll," the Annual of Leeds University Oriental Society I (1958/59): 5-24

F.F. Bruce, "The Dead Sea Habakkuk Scroll," The Annual of Leeds University Oriental Society I (1958/59): 5-24. The Dead Sea Habakkuk Scroll1 Professor F. F. Bruce, M.A., D.D. [p.5] The Dead Sea Habakkuk Scroll (1Q p Hab.) is one of the four scrolls from Qumran Cave I which were obtained in June 1947 by the Syrian Monastery of St. Mark in Jerusalem and subsequently (February 1955) purchased by the state of Israel. The scroll, which contains 13 columns of Hebrew writing, consists of two pieces of soft leather sewn together with linen thread between columns 7 and 8. The columns are about 10 centimetres wide; the scroll was originally about 160 centimetres long. The first two columns, however, are badly mutilated, as is also the bottom of the scroll; this produces an undulating break. along the bottom when the scroll is unrolled. The present maximum height of the scroll is 13.7 centimetres; originally it may have been 16 centimetres high or more. Palaeographical estimates of the age of the scroll vary by some decades, but a date around the middle of the first century B.C. or shortly afterwards is probable. The scroll contains the text of the first two chapters of Habakkuk. The book of Habakkuk, as we know it, consists of two documents: (a) ‘The oracle of God which Habakkuk the prophet saw’ (chapters 1 and 2), and (b) ‘A prayer of Habakkuk the prophet, according to Shigionoth’ (chapter 3). Our scroll quotes one or several clauses from the former document, and supplies a running commentary on the words quoted; but it does not contain the text of the second document, nor, does it make any comment on it. -

A Study on the Teacher of Righteousness, Collective Memory, and Tradition at Qumran by Gianc

MANUFACTURING HISTORY AND IDENTITY: A STUDY ON THE TEACHER OF RIGHTEOUSNESS, COLLECTIVE MEMORY, AND TRADITION AT QUMRAN BY GIANCARLO P. ANGULO A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Religion May 2014 Winston Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Kenneth G. Hoglund, Ph.D., Advisor Jarrod Whitaker, Ph.D., Chair Clinton J. Moyer, Ph.D. Acknowledgments It would not be possible to adequately present the breadth of my gratitude in the scope of this short acknowledgment section. That being said, I would like to extend a few thanks to some of those who have most influenced my academic and personal progression during my time in academia. To begin, I would be remiss not to mention the many excellent professors and specifically Dr. Erik Larson at Florida International University. The Religious Studies department at my undergraduate university nurtured my nascent fascination with religion and the Dead Sea Scrolls and launched me into the career I am now seeking to pursue. Furthermore, a thank you goes out to my readers Dr. Jarrod Whitaker and Dr. Clinton Moyer. You have both presented me with wonderful opportunities during my time at Wake Forest University that have helped to develop me into the student and speaker I am today. Your guidance and review of this thesis have proven essential for me to produce my very best work. Also, a very special thank you must go out to my advisor, professor, and friend, Dr. Ken Hoglund. -

David Flusser on the Historical Jesus David Flusser, Jesus, in Collaboration with R

VII / 1999 / 1 / Rozhledy David Flusser on the Historical Jesus David Flusser, Jesus, in collaboration with R. Steven Notley, Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University 1998,316 pages, 2 plates. Stanislav Segert The last book of David Flusser represents a synthesis of his previous and recent work. It is based on thorough research of direct sources within the New Testament and of its Jewish background. Many statements agree with prevailing views of New Testament scholars, in many important matters Flusser offers new, well substantiated ideas. Some of them are discussed here below The first edition was published in 1997, the second edition, corrected and augmented, in 1998. In the the preface (13-17) dated in 1997 Flusser explains purpose and background of his new book entitled Jesus. This biography reflects the truism that Jesus was a Jew who wanted to remain within the Jewish faith, and also argues that the teaching of Jesus is based on contempo rary Jewish faith. The new biography of Jesus is a thorough reworking of the previous book which appeared in German in 1968 and in English translation in 1969. R. Steven Notley, a former student of Flusser, now Assistant Professor at Jerusalem University College, contributed the foreword (9-12). Notley assisted in revising the English previous version and also added some contributions. Notley appreciates Flusser's scholarship and his personal contact with Jesus message. The biography of Jesus is presented in 12 chapters (18-177), supple mentary studies are offered in chapters 13-20 (179-275). At the end of the volume are useful additions: chronological table (277- 279), bibliography (280-284), index of sources (285-299) and index of subjects (300-316). -

The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Eruditio Ardescens The Journal of Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 1 February 2016 The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls J. Randall Price Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/jlbts Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Price, J. Randall (2016) "The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls," Eruditio Ardescens: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/jlbts/vol2/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eruditio Ardescens by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls J. Randall Price, Ph.D. Center for Judaic Studies Liberty University [email protected] Recent unrest in the Middle East regularly stimulates discussion on the eschatological interpretation of events within the biblical context. In light of this interest it is relevant to consider the oldest eschatological interpretation of biblical texts that had their origin in the Middle East – the Dead Sea Scrolls. This collection of some 1,000 and more documents that were recovered from caves along the northwestern shores of the Dead Sea in Israel, has become for scholars of both the Old and New Testaments a window into Jewish interpretation in the Late Second Temple period, a time known for intense messianic expectation. The sectarian documents (non-biblical texts authored by the Qumran Sect or collected by the Jewish Community) among these documents are eschatological in nature and afford the earliest and most complete perspective into the thinking of at least one Jewish group at the time of Jesus’ birth and the formation of the early church. -

The Punishment of the Wicked Priest and the Death of Judas

THE PUNISHMENT OF THE WICKED PRIEST AND THE DEATH OF JUDAS RICK VAN DE WATER Jerusalem In a recent reassesment of Jonathan the Hasmonean as the Wicked Priest of the Qumran pesharim, the claim has been made that all other theories have been refuted Òonce and for all.Ó1 There appears to have been little response to this claim, perhaps in part because that identi cation already enjoys something of a consensus. One of the main arguments for Jonathan has always been his death at the hands of gentiles (exe- cuted by Tryphon in 142 BCE), which is supposed to agree with what is said of the demise of the Wicked Priest in 1QpHab and 4Q171. 2 According to H. Stegemann, the Habakkuk pesher even agrees with JonathanÕs death outside Judea. 3 On the other hand, there are a number of reasons why such con dence in identifying Jonathan as the Wicked Priest is misleading. To begin with, StegemannÕs assertion was based on a highly ques- tionable interpretation of the above-mentioned pesher.4 J. Carmignac and W. Brownlee have criticized taking as past events what could actually refer to future punishment, according to the verb tenses. 5 The 1 E. Puech, ÒJonathan le prtre impie et les dbuts de la communaut de Qumran. 4QJonathan (4Q523) et 4QPsAp (4Q448),Ó RevQ 17 (1996) 241 –70, esp. 269. 2 E.g. G. Jeremias, Der Lehrer der Gerechtigkeit (SUNT 2; Gšttingen, 1963) 75. A.S. van der Woude has recently asserted that Òall commentatorsÓ see 1QpHab 9:9 –12 as JonathanÕs murder by Tryphon (ÒOnce Again: The Wicked Priests in the Habakkuk Pesher from Cave 1 of Qumran,Ó RevQ 17 [1996] 383). -

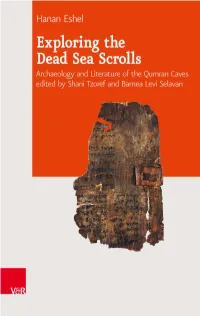

Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls

Hanan Eshel, Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls © 2015, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525550960 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647550961 Hanan Eshel, Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls Journal of Ancient Judaism Supplements Edited by Armin Lange, Bernard M. Levinson and Vered Noam Advisory Board Katell Berthelot (University of Aix-Marseille), George Brooke (University of Manchester), Jonathan Ben Dov (University of Haifa), Beate Ego (University of Osnabrück), Esther Eshel (Bar-Ilan University), Heinz-Josef Fabry (University of Bonn), Steven Fraade (Yale University), Maxine L. Grossman (University of Maryland), Christine Hayes (Yale University), Catherine Hezser (University of London), Alex Jassen (University of Minnesota), James L. Kugel (Bar-Ilan University), Jodi Magness (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Carol Meyers, (Duke University), Eric Meyers (Duke University), Hillel Newman (University of Haifa), Christophe Nihan (University of Lausanne), Lawrence H. Schiffman (New York University), Konrad Schmid (University of Zurich), Adiel Schremer (Bar-Ilan University), Michael Segal (Hebrew University of Jerusalem), Aharon Shemesh (Bar-Ilan University), Günter Stemberger (University of Vienna), Kristin De Troyer (University of St. Andrews), Azzan Yadin (Rutgers University) Volume 18 Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2015, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525550960 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647550961 Hanan Eshel, Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls Hanan Eshel Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls Archaeology and Literature of the Qumran Caves edited by Shani Tzoref / Barnea Levi Selavan Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2015, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525550960 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647550961 Hanan Eshel, Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls This volume is generously sponsored by the David and Jemima Jeselsohn Epigraphic Center for Jewish History.