Fundamentals of Theoretical Organic Chemistry Lecture 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactions of Benzene & Its Derivatives

Organic Lecture Series ReactionsReactions ofof BenzeneBenzene && ItsIts DerivativesDerivatives Chapter 22 1 Organic Lecture Series Reactions of Benzene The most characteristic reaction of aromatic compounds is substitution at a ring carbon: Halogenation: FeCl3 H + Cl2 Cl + HCl Chlorobenzene Nitration: H2 SO4 HNO+ HNO3 2 + H2 O Nitrobenzene 2 Organic Lecture Series Reactions of Benzene Sulfonation: H 2 SO4 HSO+ SO3 3 H Benzenesulfonic acid Alkylation: AlX3 H + RX R + HX An alkylbenzene Acylation: O O AlX H + RCX 3 CR + HX An acylbenzene 3 Organic Lecture Series Carbon-Carbon Bond Formations: R RCl AlCl3 Arenes Alkylbenzenes 4 Organic Lecture Series Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution • Electrophilic aromatic substitution: a reaction in which a hydrogen atom of an aromatic ring is replaced by an electrophile H E + + + E + H • In this section: – several common types of electrophiles – how each is generated – the mechanism by which each replaces hydrogen 5 Organic Lecture Series EAS: General Mechanism • A general mechanism slow, rate + determining H Step 1: H + E+ E El e ctro - Resonance-stabilized phile cation intermediate + H fast Step 2: E + H+ E • Key question: What is the electrophile and how is it generated? 6 Organic Lecture Series + + 7 Organic Lecture Series Chlorination Step 1: formation of a chloronium ion Cl Cl + + - - Cl Cl+ Fe Cl Cl Cl Fe Cl Cl Fe Cl4 Cl Cl Chlorine Ferric chloride A molecular complex An ion pair (a Lewis (a Lewis with a positive charge containing a base) acid) on ch lorine ch loronium ion Step 2: attack of -

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just Like an Alkene, Benzene Has Clouds of Electrons Above and Below Its Sigma Bond Framework

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just like an alkene, benzene has clouds of electrons above and below its sigma bond framework. Although the electrons are in a stable aromatic system, they are still available for reaction with strong electrophiles. This generates a carbocation which is resonance stabilized (but not aromatic). This cation is called a sigma complex because the electrophile is joined to the benzene ring through a new sigma bond. The sigma complex (also called an arenium ion) is not aromatic since it contains an sp3 carbon (which disrupts the required loop of p orbitals). Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page1 The loss of aromaticity required to form the sigma complex explains the highly endothermic nature of the first step. (That is why we require strong electrophiles for reaction). The sigma complex wishes to regain its aromaticity, and it may do so by either a reversal of the first step (i.e. regenerate the starting material) or by loss of the proton on the sp3 carbon (leading to a substitution product). When a reaction proceeds this way, it is electrophilic aromatic substitution. There are a wide variety of electrophiles that can be introduced into a benzene ring in this way, and so electrophilic aromatic substitution is a very important method for the synthesis of substituted aromatic compounds. Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page2 Bromination of Benzene Bromination follows the same general mechanism for the electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS). Bromine itself is not electrophilic enough to react with benzene. But the addition of a strong Lewis acid (electron pair acceptor), such as FeBr3, catalyses the reaction, and leads to the substitution product. -

AROMATIC NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION-PART -2 Electrophilic Substitution

Dr. Tripti Gangwar AROMATIC NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION-PART -2 Electrophilic substitution ◦ The aromatic ring acts as a nucleophile, and attacks an added electrophile E+ ◦ An electron-deficient carbocation intermediate is formed (the rate- determining step) which is then deprotonated to restore aromaticity ◦ electron-donating groups on the aromatic ring (such as -OH, -OCH3, and alkyl) make the reaction faster, since they help to stabilize the electron-poor carbocation intermediate ◦ Lewis acids can make electrophiles even more electron-poor (reactive), increasing the reaction rate. For example FeBr3 / Br2 allows bromination to occur at a useful rate on benzene, whereas Br2 by itself is slow). In fact, a substitution reaction does occur! (But, as you may suspect, this isn’t an electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction.) In this substitution reaction the C-Cl bond breaks, and a C-O bond forms on the same carbon. The species that attacks the ring is a nucleophile, not an electrophile The aromatic ring is electron-poor (electrophilic), not electron rich (nucleophilic) The “leaving group” is chlorine, not H+ The position where the nucleophile attacks is determined by where the leaving group is, not by electronic and steric factors (i.e. no mix of ortho– and para- products as with electrophilic aromatic substitution). In short, the roles of the aromatic ring and attacking species are reversed! The attacking species (CH3O–) is the nucleophile, and the ring is the electrophile. Since the nucleophile is the attacking species, this type of reaction has come to be known as nucleophilic aromatic substitution. n nucleophilic aromatic substitution (NAS), all the trends you learned in electrophilic aromatic substitution operate, but in reverse. -

19.1 Ketones and Aldehydes

19.1 Ketones and Aldehydes • Both functional groups possess the carbonyl group • Important in both biology and industry Simplest aldehyde Simplest ketone used as a used mainly as preservative a solvent Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. 19-1 Klein, Organic Chemistry 3e 19.1 Ketones And Aldehydes Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. 19-2 Klein, Organic Chemistry 3e 19.2 Nomenclature • Four discrete steps to naming an aldehyde or ketone • Same procedure as with alkanes, alcohols, etc… 1. Identify and name the parent chain 2. Identify the name of the substituents (side groups) 3. Assign a locant (number) to each substituents 4. Assemble the name alphabetically Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. 19-3 Klein, Organic Chemistry 3e 19.2 Nomenclature 1. Identify and name the parent chain – For aldehydes, replace the “-e” ending with an “-al” – the parent chain must include the carbonyl carbon Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. 19-4 Klein, Organic Chemistry 3e 19.2 Nomenclature 1. Identify and name the parent chain – The aldehydic carbon is assigned number 1: Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. 19-5 Klein, Organic Chemistry 3e 19.2 Nomenclature 1. Identify and name the parent chain – For ketones, replace the “-e” ending with an “-one” – The parent chain must include the C=O group – the C=O carbon is given the lowest #, and can be expressed before the parent name or before the suffix Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. -

Aromatic Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction

Aromatic Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction DR. RAJENDRA R TAYADE ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE, NAGPUR Principles There are four principal mechanisms for aromatic nucleophilic substitution which are similar to that of aliphatic nucleophilic substitution. (SN1, SN2, SNi, SET Mechanism) 1. SNAr Mechanism- addition / elimination CF3, CN, CHO, COR, COOH, Br, Cl, I Common Activating Groups for NAS Step [1] Addition of the nucleophile (:Nu–) to form a carbanion Addition of the nucleophile (:Nu–) forms a resonance-stabilized carbanion with a new C – Nu bond— three resonance structures can be drawn. • Step is rate-determining • Aromaticity of the benzene ring is lost Step [2] loss of the leaving group re-forms the aromatic ring. • This step is fast because the aromaticity of the benzene ring is restored. ? Explain why a methoxy group (CH3O) increases the rate of electrophilic aromatic substitution, but decreases the rate of nucleophilic aromatic substitution. 2.ArSN1 Mechanism- elimination /addition • This mechanism operates in the reaction of diazonium salts with nucleophiles. •The driving force resides in the strength of the bonding in the nitrogen molecule that makes it a particularly good leaving group. 3.Benzyne Mechanism- elimination /addition Step [1] Elimination of HX to form benzyne Elimination of H and X from two adjacent carbons forms a reactive benzyne intermediate Step [2] Nucleophilic addition to form the substitution product Addition of the nucleophile (–OH in this case) and protonation form the substitution product Evidence for the Benzyne Mechanism Trapping in Diels/Alder Reaction O O B E N Z Y N E C C O O O D i e l s / A l d e r O N H 3 N N Dienophile Diene A d d u c t Substrate Modification – absence of a hydrogens LG Substituent Substituent No Reaction Base Isotopic Labeling LG Nu H Nu Structure of Benzyne • The σ bond is formed by overlap of two sp2 hybrid orbitals. -

A Marcus-Theory-Based Approach to Ambident Reactivity

Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München A Marcus-Theory-Based Approach to Ambident Reactivity Robert Martin Breugst aus München 2010 Erklärung Diese Dissertation wurde im Sinne von § 13 Abs. 3 bzw. 4 der Promotionsordnung vom 29. Januar 1998 (in der Fassung der vierten Änderungssatzung vom 26. November 2004) von Herrn Professor Dr. Herbert Mayr betreut. Ehrenwörtliche Versicherung Diese Dissertation wurde selbständig, ohne unerlaubte Hilfe erarbeitet. München, 28.10.2010 _________________________ Dissertation eingereicht am: 28.10.2010 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Herbert Mayr 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Hendrik Zipse Mündliche Prüfung am: 21.12.2010 II Acknowledgements Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to express my cordial gratitude to Professor Dr. Herbert Mayr for the opportunity to compose this thesis in his group. I have cherished all the valuable discussions with him, his endless support, and his inspiring confidence very much and I have always appreciated working under these excellent conditions. From the very first day in his group Professor Mayr made me feel welcome, has always been willing to discuss my ideas, and encouraged me to pursue a scientific career. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Hendrik Zipse for numerous discussions and helpful comments on quantum chemical calculations, and of course also for reviewing my thesis. Additionally, I am very indebted to Professor J. Peter Guthrie, Ph.D., for giving me the opportunity to spend almost 4 months in his group at the University of Western Ontario. During this time, I have learned so many new things and I am grateful for the reams of discussions in his office. -

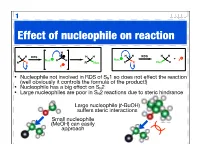

Effect of Nucleophile on Reaction

1 Effect of nucleophile on reaction H H H H H H H RDS H H RDS + Nuc R H Nuc X R X R Nuc R X Nuc R X • Nucleophile not involved in RDS of SN1 so does not effect the reaction (well obviously it controls the formula of the product!) • Nucleophile has a big effect on SN2 • Large nucleophiles are poor in SN2 reactions due to steric hindrance Large nucleophile (t-BuOH) suffers steric interactions Small nucleophile (MeOH) can easily approach 2 Nucleophile strength • The stronger the nucleophile the faster / more efficient the SN2 reaction • Nucleophilic strength (nucleophilicity) relates to how easily a compound can donate an electron pair • The more electronegative an atom the less nucleophilic as the electrons are held closer nucleophilic strength Anion more nucleophilic H O than its neutral analogue (basicity) HO > 2 nucleophilic strength R C (basicity) 3 > R2N > RO > F As we move along a row the electronegativity electronegativity C < N < O < F increases and nucleophilic strength nucleophilicity decreases (basicity) R NH2 > R OH > R F As we go down a group both anions and neutral atoms get more nucleophilic strength H2S > H2O (basicity) nucleophilic - electrons I > Br > Cl > F not held as tightly as size increases 3 Solvent effects SN1 • Intermediate - the carbocation - is stabilised by polar solvents • Leaving group stabilised by protic solvents (encourages dissociation) • Water, alcohols & carboxylic acids good solvents for SN1 Br H O H O H H Br O H O H O cation hydrogen stabilised O bonds SN2 • Prefer less polar, aprotic solvents • Less -

Reactions of Alkenes Since Bonds Are Stronger Than Bonds, Double Bonds Tend to React to Convert the Double Bond Into Bonds

Reactions of Alkenes Since bonds are stronger than bonds, double bonds tend to react to convert the double bond into bonds This is an addition reaction. (Other types of reaction have been substitution and elimination). Addition reactions are typically exothermic. Electrophilic Addition The bond is localized above and below the C-C bond. The electrons are relatively far away from the nuclei and are therefore loosely bound. An electrophile will attract those electrons, and can pull them away to form a new bond. This leaves one carbon with only 3 bonds and a +ve charge (carbocation). The double bond acts as a nucleophile (attacks the electrophile). Ch08 Reacns of Alkenes (landscape) Page 1 In most cases, the cation produced will react with another nucleophile to produce the final overall electrophilic addition product. Electrophilic addition is probably the most common reaction of alkenes. Consider the electrophilic addition of H-Br to but-2-ene: The alkene abstracts a proton from the HBr, and a carbocation and bromide ion are generated. The bromide ion quickly attacks the cationic center and yields the final product. In the final product, H-Br has been added across the double bond. Ch08 Reacns of Alkenes (landscape) Page 2 Orientation of Addition Consider the addition of H-Br to 2-methylbut-2-ene: There are two possible products arising from the two different ways of adding H-Br across the double bond. But only one is observed. The observed product is the one resulting from the more stable carbocation intermediate. Tertiary carbocations are more stable than secondary. -

Chapter 11: Nucleophilic Substitution and Elimination Walden Inversion

Chapter 11: Nucleophilic Substitution and Elimination Walden Inversion O O PCl5 HO HO OH OH O OH O Cl (S)-(-) Malic acid (+)-2-Chlorosuccinic acid [a]D= -2.3 ° Ag2O, H2O Ag2O, H2O O O HO PCl5 OH HO OH O OH O Cl (R)-(+) Malic acid (-)-2-Chlorosuccinic acid [a]D= +2.3 ° The displacement of a leaving group in a nucleophilic substitution reaction has a defined stereochemistry Stereochemistry of nucleophilic substitution p-toluenesulfonate ester (tosylate): converts an alcohol into a leaving group; tosylate are excellent leaving groups. abbreviates as Tos C X Nu C + X- Nu: X= Cl, Br, I O Cl S O O + C OH C O S CH3 O CH3 tosylate O -O S O O Nu C + Nu: C O S CH3 O CH3 1 O Tos-Cl - H3C O O H + TosO - H O H pyridine H O Tos O CH3 [a]D= +33.0 [a]D= +31.1 [a]D= -7.06 HO- HO- O - Tos-Cl H3C O - H O O TosO + H O H pyridine Tos H O CH3 [a]D= -7.0 [a]D= -31.0 [a]D= -33.2 The nucleophilic substitution reaction “inverts” the Stereochemistry of the carbon (electrophile)- Walden inversion Kinetics of nucleophilic substitution Reaction rate: how fast (or slow) reactants are converted into product (kinetics) Reaction rates are dependent upon the concentration of the reactants. (reactions rely on molecular collisions) H H Consider: HO C _ _ C Br Br HO H H H H At a given temperature: If [OH-] is doubled, then the reaction rate may be doubled If [CH3-Br] is doubled, then the reaction rate may be doubled A linear dependence of rate on the concentration of two reactants is called a second-order reaction (molecularity) 2 H H HO C _ _ C Br Br HO H H H H Reaction rates (kinetic) can be expressed mathematically: reaction rate = disappearance of reactants (or appearance of products) For the disappearance of reactants: - rate = k [CH3Br] [OH ] [CH3Br] = CH3Br concentration [OH-] = OH- concentration k= constant (rate constant) L mol•sec For the reaction above, product formation involves a collision between both reactants, thus the rate of the reaction is dependent upon the concentration of both. -

Activation of Alcohols Toward Nucleophilic Substitution: Conversion of Alcohols to Alkyl Halides Amani Atiyalla Abdugadar

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Theses Student Research 12-1-2012 Activation of Alcohols Toward Nucleophilic Substitution: Conversion of Alcohols to Alkyl Halides Amani Atiyalla Abdugadar Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses Recommended Citation Abdugadar, Amani Atiyalla, "Activation of Alcohols Toward Nucleophilic Substitution: Conversion of Alcohols to Alkyl Halides" (2012). Theses. Paper 22. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2012 Amani Abdugadar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School ACTIVATION OF ALCOHOLS TOWARD NEOCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION: CONVERSION OF ALCOHOLS TO ALKYL HALIDES A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Amani Abdugadar College of Natural and Health Sciences Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry December, 2012 This Thesis by: Amani Abdugadar Entitled: Activation of Alcohols Toward Neocleophilic Substitution: Conversion of Alcohols to Alkyl Halides has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Master of Science in College of Natural and Health Sciences in Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry Accepted by the Thesis Committee ______________________________________________________ Michael D. Mosher, Ph.D., Research Co-Advisor ______________________________________________________ Richard W. Schwenz, Ph.D., Research Co-Advisor ______________________________________________________ David L. Pringle, Ph.D., Committee Member Accepted by the Graduate School _________________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D., LPC Acting Dean of the Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Abdugadar, Amani. -

Pyridine System: the Local Hard and Soft Acids and Bases Principle Perspective Journal of the Mexican Chemical Society, Vol

Journal of the Mexican Chemical Society ISSN: 1870-249X [email protected] Sociedad Química de México México Richaud, Arlette; Méndez, Francisco Nucleophilic Attack at the Pyridine Nitrogen Atom in a Bis(imino)pyridine System: The Local Hard and Soft Acids and Bases Principle Perspective Journal of the Mexican Chemical Society, vol. 56, núm. 3, julio-septiembre, 2012, pp. 351-354 Sociedad Química de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=47524533019 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2012, 56(3), 351-354 ArticleNucleophilic Attack at the Pyridine Nitrogen Atom in a Bis(imino)pyridine System: The Local Hard and© Soft 2012, Acids Sociedad and Bases Química de México351 ISSN 1870-249X Nucleophilic Attack at the Pyridine Nitrogen Atom in a Bis(imino)pyridine System: The Local Hard and Soft Acids and Bases Principle Perspective Arlette Richaud and Francisco Méndez* Departamento de Química, División de Ciencias Básicas e Ingeniería, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, A.P. 55-534, México, D.F., 09340 México. Dedicated to José Luis Gázquez Received January 06, 2012; accepted June 04, 2012 Abstract. Motivated by the unprecedented nucleophilic attack at the Resumen. Motivados por el ataque nucleofílico sin precedentes sobre pyridine nitrogen atom in bis(imino)pyridines, observed by Gambaro- el átomo de nitrógeno de la piridina en bis(imino)piridinas observado tta et al. -

Nucleophilic Addition to the Carbonyl Group 6

Nucleophilic addition to the carbonyl group 6 Connections Building on Arriving at Looking forward to • Functional groups, especially the C=O • How and why the C=O group reacts • Additions of organometallic group ch2 with nucleophiles reagents ch9 • Identifying the functional groups in a • Explaining the reactivity of the C=O • Substitution reactions of the C=O molecule spectroscopically ch3 group using molecular orbitals and curly group’s oxygen atom ch11 • How molecular orbitals explain arrows • How the C=O group in derivatives of molecular shapes and functional • What sorts of molecules can be made by carboxylic acids promotes substitution groups ch4 reactions of C=O groups reactions ch10 • How, and why, molecules react together • How acid or base catalysts improve the • C=O groups with an adjacent double and using curly arrows to describe reactivity of the C=O group bond ch22 reactions ch5 Molecular orbitals explain the reactivity of the carbonyl group We are now going to leave to one side most of the reactions you met in the last chapter—we will come back to them all again later in the book. In this chapter we are going to concentrate on just one of them—probably the simplest of all organic reactions—the addition of a nucleo- phile to a carbonyl group. The carbonyl group, as found in aldehydes, ketones, and many other compounds, is without doubt the most important functional group in organic chemis- try, and that is another reason why we have chosen it as our fi rst topic for more detailed study. You met nucleophilic addition to a carbonyl group on pp.