View Published in the Times Magazine, It Was Noted That Joachim Performed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Joachim, David Laurie, and Mischa Elman: Revising the Provenance

Joseph Joachim, David Laurie, and Mischa Elman: revising the provenance © Nicholas Sackman New version, 2020 Charles-Nicolas-Eugène Gand, in his Catalogue descriptif des Instruments de Stradivarius et J. Guarnerius, writes descriptions of four Stradivari violins belonging to Charles Lamoureux, the French conductor and violinist (1834-1899): Upper part of Gand’s Catalogue descriptif page 18 (hereafter G18U) (année 1870) Monsieur Lamoureux, Paris Violon Stradivarius, 13 pouces 1 ligne ½, année 1735 Fond de deux pièces presqu’uni, éclisse plus veinées, très-belle table et très-belle tête. Les filets sont un peu écartés dans certains endroits. Vernis rouge doré, très-beau. Complètement intact. Ex marquis de Louvencourt [this annotation written by Gand using red ink] (1870) Mr Lamoureux, Paris Antonio Stradivari violin, 13 pouces, 1½ lignes [355.3mm], year 1735 The back plate is made from two pieces; almost plain. The ribs are more flamed. Very beautiful front plate and very beautiful head. There are slight gaps in the purfling in some areas. The varnish is golden red, very beautiful. Completely intact. ex Marquis de Louvencourt. This 1735 violin has no association with Joseph Joachim, David Laurie, or Mischa Elman. ___________ Lower part of page 18 (G18L) [Monsieur Lamoureux] (année 1870) Violon Stradivarius, 13 pouces 2 lignes, année 1722 Fond de deux pièces, veines un peu serrées remontant un peu, belles éclisses, table de deux pièces ayant une petite cassure à l’âme, une petite au menton près du cordier, marque d’usure faite par l’archet, tête beau modèle. Vernis rouge doré clair. 187 M r Accursi, 5,000 } 1874 M r Laurie, 5,500 } red ink 1886 M r Joachim. -

From the Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz

CoNSERVATORY oF Music presents The Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz SPOTLIGHT ON YOUNG VIOLIN VIRTUOSI with Tao Lin, piano Saturday, April 3, 2004 7:30p.m. Amamick-Goldstein Concert Hall de Hoernle International Center Program Polonaise No. 1 in D Major ..................................................... Henryk Wieniawski Gabrielle Fink, junior (United States) (1835 - 1880) Tambourin Chino is ...................................................................... Fritz Kreisler Anne Chicheportiche, professional studies (France) (1875- 1962) La Campanella ............................................................................ Niccolo Paganini Andrei Bacu, senior (Romania) (1782-1840) (edited Fritz Kreisler) Romanza Andaluza ....... .. ............... .. ......................................... Pablo de Sarasate Marcoantonio Real-d' Arbelles, sophomore (United States) (1844-1908) 1 Dance of the Goblins .................................................................... Antonio Bazzini Marta Murvai, senior (Romania) (1818- 1897) Caprice Viennois ... .... ........................................................................ Fritz Kreisler Danut Muresan, senior (Romania) (1875- 1962) Finale from Violin Concerto No. 1 in g minor, Op. 26 ......................... Max Bruch Gareth Johnson, sophomore (United States) (1838- 1920) INTERMISSION 1Ko<F11m'1-za from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor .................... Henryk Wieniawski ten a Ilieva, freshman (Bulgaria) (1835- 1880) llegro a Ia Zingara from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

Tertis's Viola Version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to Clevelandclassical

Preview Heights Chamber Orchestra conductor's notes: Tertis's viola version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to ClevelandClassical An old adage suggested that violists were merely vio- linists-in-decline. That was before Lionel Tertis! He was born in 1876 of musical parents who had come to England from Poland and Russia and, at three years old, he started playing the piano. At six he performed in public, but had to be locked in a room to make him practice, a procedure that has actually fostered many an international virtuoso. At thirteen, with the agree- ment of his parents, he left home to earn his living in music playing in pickup groups at summer resorts, accompanying a violinist, and acting as music attendant at a lunatic asylum. +41:J:-:/1?<1>95@@1041?@A0510-@(>5:5@E;88131;2!A?5/@-75:3B5;85:-?45? "second study," but concentrating on the piano and playing concertos with the school or- chestra. As sometime happens, his violin teacher showed little interest in a second study <A<58-:01B1:@;8045?2-@41>@4-@41C-?.1@@1>J@@102;>@413>;/1>E@>-01 +5@4?A/4 encouragement, Tertis decided he had to teach himself. Fate intervened when fellow stu- dents wanted to form a string quartet. Tertis volunteered to play viola, borrowed an in- strument, loved the rich quality of its lowest string and thereafter turned the old adage up- side down: a not very obviously gifted violinist becoming a world class violist. But, until the viola attained respectability in Tertis’s hands, composers were reluctant to write for the instrument. -

Current Review

Current Review Christian Ferras plays Beethoven and Berg Violin Concertos aud 95.590 EAN: 4022143955906 4022143955906 Fanfare (Robert Maxham - 2012.05.01) Audite’s program of violin concertos by Ludwig van Beethoven and Alban Berg captures two moments in the life of Christian Ferras, the first a studio recording from November 19, 1951, made in the Jesus-Christus-Kirche after the 18-year-old violinist had given a live performance of the work at the Titania Palast and more than a decade before he would record the work with Herbert von Karajan and the same orchestra. The young Ferras sounds both flexible and sprightly in the first movement’s passagework, producing a suave tone that might be described as almost gustatory in its effect as he soars above the orchestra. That tone lacks the sharp edge of Zino Francescatti’s and even the slightly reedy quality of Arthur Grumiaux’s, and he never seems to be deploying it simply for the sheer beauty of it: As sumptuous as it might sound, it always serves his high-minded concept of the work itself. And his playing of Fritz Kreisler’s famous cadenza similarly subordinates virtuosity to musical effect. Karl Böhm sets the mood for a probing exploration of the slow movement, in which Ferras sounds similarly committed; he never allows himself to be diverted into mannerism or eccentricity, as Anne-Sophie Mutter does in her performance with Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon 289 471 349, Fanfare 26:5 and 26:6). What the young Michael Rabin achieved in the showpieces of Wieniawski and Paganini, Ferras arguably exceeded in the music of Beethoven. -

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations

Dissertation Summary of Three Recitals, with Works Derived from Folk Influences, Living American Composers and Works Containing a Theme and Variations. by Heewon Uhm A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Halen, Chair Professor Anthony D. Elliott Professor Freda A. Herseth Professor Andrew W. Jennings Assisant Professor Youngju Ryu Heewon Uhm [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8334-7912 © Heewon Uhm 2019 DEDICATION To God For His endless love To my dearest teacher, David Halen For inviting me to the beautiful music world with full of inspiration To my parents and sister, Chang-Sub Uhm, Sunghee Chun, and Jungwon Uhm For trusting my musical journey ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF EXAMPLES iv ABSTRACT v RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 9 Recital 2 Program 9 Recital 2 Program Notes 10 RECITAL 3 18 Recital 3 Program 18 Recital 3 Program Notes 19 BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 iii LIST OF EXAMPLES EXAMPLE Ex-1 Semachi Rhythm 15 Ex-2 Gutgeori Rhythm 15 Ex-3 Honzanori-1, the transformed version of Semachi and Gutgeori rhythm 15 iv ABSTRACT In lieu of a written dissertation, three violin recitals were presented. Recital 1: Theme and Variations Monday, November 5, 2018, 8:00 PM, Stamps Auditorium, Walgreen Drama Center, University of Michigan. Assisted by Joonghun Cho, piano; Hsiu-Jung Hou, piano; Narae Joo, piano. Program: Olivier Messiaen, Thème et Variations; Johann Sebastian Bach, Ciaconna from Partita No. -

825646079247.Pdf

FRITZ KREISLER 1875–1962 1 Caprice viennois, Op.2 3.59 2 Andantino in the style of Martini 3.41 3Allegretto in the style of Boccherini 3.18 4 La gitana 3.12 5 Slavonic Dance , Op.72 no.8 (Dvo ˇrák, arr. Kreisler) 5.27 6 Chanson Louis XIII & Pavane in the style of Couperin 4.06 7 Schön Rosmarin 1.57 8 Liebesfreud 3.18 9 Danse espagnole (from Falla La vida breve , arr. Kreisler) 3.24 10 Liebesleid 3.25 11 Recitativo & Scherzo capriccio, Op.6 4.03 12 Tango (Albéniz, arr. Kreisler) 2.32 13 Rondino on a theme by Beethoven 2.42 14 Tambourin chinois, Op.3 3.35 Arrangements by Fritz Kreisler 15 TARTINI Violin Sonata in G minor “Devil’s Trill” 14.41 16 POLDINI Dancing Doll 2.44 17 WIENIAWSKI Caprice 1.33 18 TRAD. Londonderry Air 4.33 19 MOZART Rondo (from Serenade in D, K250 “Haffner”) 7.00 20 CORELLI Sarabande & Allegretto 4.00 21 ALBÉNIZ Malagueña, Op.165 no.3 4.20 22 HEUBERGER Midnight Bells (from Der Opernball ) 3.42 23 BRAHMS Hungarian Dance in F minor 3.56 24 MENDELSSOHN Song Without Words, Op.62 no.1 3.16 25 KREISLER La Précieuse in the style of Couperin 2.44 26 KREISLER Siciliano & Rigaudon in the style of Francœur 5.09 27 CHAMINADE Sérénade espagnole, Op.150 (arr. Kreisler) 2.13 28 KREISLER Aubade provençale in the style of Couperin 2.32 29 KREISLER Menuet in the style of Porpora 4.02 30 LEHÁR Serenade (from Frasquita , arr. -

Download Booklet

572291bk Women EU 30/7/10 12:57 Page 4 Clare Howick Clare Howick has established herself as one of the leading violinists of her BRITISH WOMEN generation. She has a special interest in twentieth-century British violin repertoire which has resulted in a number of premières and recordings. Her début disc, Sonata Lirica and Other Works by Cyril Scott was Editor’s Choice in COMPOSERS Gramophone magazine. A second disc of Cyril Scott’s violin sonatas was subsequently recorded for Naxos (8.572290). She has performed most of the violin concerto repertoire with various orchestras including the Philharmonia Smyth • Maconchy • Poldowski Orchestra, has appeared at major festivals in Britain, including the Cheltenham International Festival, and has broadcast on BBC Radio 3. She combines solo and chamber performances with appearing as guest leader of many orchestras, Tate • Barns including the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Ulster Orchestra and the Orchestra of English National Opera. She Clare Howick, Violin • Sophia Rahman, Piano gratefully acknowledges the loan of a Stradivarius violin (1721) for this recording. Photograph: Guy Mayer Sophia Rahman Sophia Rahman has recorded over twenty chamber discs for companies including Naxos, ASV, Dutton/Epoch, Meridian, Linn Records, and Guild, among others. Her career encompasses solo, chamber and coaching activities. She acts as an official accompanist for the Lionel Tertis International Viola Competition, the Barbirolli International Oboe Competition and IMS/Prussia Cove. She has given master-classes in China at the Conservatory of Music in Xi An and the Xing Hai Conservatory of Music in Guangzhou, in Russia at the Modest Mussorgsky College in St Petersburg, in Sweden at Lilla Akadamien, Stockholm, and at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama. -

Wieniawski EU 2/26/08 2:01 PM Page 5

550744 bk Wieniawski EU 2/26/08 2:01 PM Page 5 Henryk Wienlawski (1835-1880) seinem Lehrer Massart gewidmet und eine glänzende nieder. Er schickte ein Telegramm an Isobels Mutter, in Kompositionen für Violine und Klavier Studie über den berühmten italienischen Tanz. dem er sie für das nächste Konzert einlud, das am Henryk Die Polonaisen, die Mazurka und der Kujawiak nächsten Tag stattfinden sollte. Auch Vater Hampton Henryk Wieniawski wurde am 10. Juni 1835 als Sohn befremdenden Streichquartette von Ludwig van zeigen Wieniawski als Meister im Umgang mit den kam, und nachdem er die Legende gehört und die des Militärarztes Tadeusz Wieniawski in Lublin Beethoven. polnischen Nationaltänzen, wohingegen die “Legende“ Reaktion seiner Tochter darauf beobachtet hatte, gab er WIENIAWSKI geboren. Seine Mutter Regina war die Tochter des Der Komponist Wieniawski hat naheliegenderweise in eine ganz andere Richtung weist. Sie ist das Zeugnis dem Paar seinen Segen. Henryk und Isobel heirateten angesehenen polnischen Pianisten Edward Wolff. wie viele seiner Kollegen sein eigenes Instrument in den seiner Liebe zu Isobel Hampton, die er zunächst nach und hatten fünf Kinder. Offenbar erkannten die Eltern früh die musikalische Mittelpunkt seiner Arbeit gestellt. Die beiden dem Willen ihres Vaters nicht heiraten sollte. Nachdem Begabung ihres Sohnes, und sie konnten es sich leisten, Violinkonzerte bilden einen Höhepunkt seines der Familienvorstand ihn in London hatte “abblitzen“ Keith Anderson Violin Showpieces ihn in die besten pädagogischen Hände zu geben: Sein Werkkatalogs; dazu kommen kammermusikalische lassen, zog sich Wieniawski zurück, um einige Stunden erster Lehrer war ein Schüler von Louis Spohr gewesen, Stücke für Violine und Klavier sowie Unterrichts- und Geige zu spielen - danach schrieb er die “Legende“ Deutsche Fassung: Cris Posslac der zweite unterrichtete unter anderem auch Joseph Anschauungsmaterial. -

Concert Program

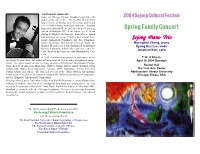

Jonathan Koh, violoncello Native of Chicago, Illinois, Jonathan began his cello 2004 Sejong Cultural Festival studies at the age of five. His teachers include Hans Jorgen Jensen of Northwestern University and Johann Lee of Seoul National Symphony Orchestra. Jonathan made his debut at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Spring Family Concert Arts in Washington D.C. at the tender age of fifteen playing the Elgar Cello Concerto. Soon after, he soloed with numerous orchestras, including the Evanston Sym- phony, Springfield Symphony, San Jose Symphony, Sejong Piano Trio Harper Symphony and Korean-American Youth Or- Myunghee Chung, piano chestras. He has been a featured soloist in Tchaikovsky’s Kyung Sun Lee, violin Rococo Variations, Kabalevsky Concerto, Lab Con- certo, Saint-Saëns Concerto, and Shostakovich Con- Jonathan Koh, cello certo. In 2001, Jonathan was invited to participate in the 7:30 - 9:30 p.m. prestigious Leonard Rose International Competition as well as other international compe- April 18, 2004 (Sunday) titions. His achievements include receiving top prizes at the Hellam International Compe- tition, Society of American Musicians, Midwest Young Artists, AACS National String Recital Hall Competition, Donna Reed Foundation, National ARTS Foundation, Yonsei University The Fine Arts Center Young Artists, and others. He also had success at the Julius Stulberg International Northeastern Illinois University Competition, Irving Klein International Competition, Johansen International Competition, Chicago, Illinois, USA and the Kingsville International Competition. He has performed under Lorin Mazel of the New York Philharmonic, Leonard Slatkin of the National Symphony, Apo Hsu of the Springfield Symphony and among others. He also served as the principal cellist of the Texas Music Festival Orchestra. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 77, 1957-1958, Subscription

*l'\ fr^j BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON 24 G> X will MIIHIi H tf SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1957-1958 BAYARD TUCEERMAN. JR. ARTHUR J. ANDERSON ROBERT T. FORREST JULIUS F. HALLER ARTHUR J. ANDERSON, JR. HERBERT 8. TUCEERMAN J. DEANE SOMERVILLE It takes only seconds for accidents to occur that damage or destroy property. It takes only a few minutes to develop a complete insurance program that will give you proper coverages in adequate amounts. It might be well for you to spend a little time with us helping to see that in the event of a loss you will find yourself protected with insurance. WHAT TIME to ask for help? Any time! Now! CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. RICHARD P. NYQUIST in association with OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description 108 Water Street Boston 6, Mast. LA fayette 3-5700 SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1957-1958 Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor CONCERT BULLETIN with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk Copyright, 1958, by Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Jacob J. Kaplan Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Talcott M. Banks Michael T. Kelleher Theodore P. Ferris Henry A. Laughlin Alvan T. Fuller John T. Noonan Francis W. Hatch Palfrey Perkins Harold D. Hodgkinson Charles H. Stockton C. D. Jackson Raymond S. Wilkins E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Oliver Wolcott TRUSTEES EMERITUS Philip R. Allen M. A. DeWolfe Howe N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Edward A. Taft Thomas D.