Civil War Prisoner: the Mysterious Mrs. Mason Alias Augusta Heath Morris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time Warp Along Telegraph Goes from Revolutionary Sites to Civil War Part Three of the Telegraph Road Series Goes to the Edge of City of Alexandria

Mount Vernon’s Hometown Newspaper • A Connection Newspaper April 16, 2020 Page, 9 Photos by Mike Salmon/The Connection by Mike Salmon/The Photos Photo Contributed Photo Historic Huntley Farm. Map by Robert Knox Sneden, a The Belvale House off Union map maker during the war. Telegraph Road. Time Warp Along Telegraph Goes From Revolutionary Sites to Civil War Part three of the Telegraph Road series goes to the edge of City of Alexandria. By Mike Salmon ly owned the house and went up was completed in 2012. The sur- Telegraph Road, near present day The Connection in the attic, saw the ghost out the rounding park is famous for a Jefferson Manor Park, was Fort window, and when they went to boardwalk that goes out over the Lyon, one of the Union forts that s Telegraph Road creeps turn on the lights, all the lights wetlands that bird watchers use on was put in place to defend Wash- along towards the City in the house blew. All this was re- a regular basis. ington, D.C. This fort was built in of Alexandria, the com- corded in a 1964 issue of the Hol- 1861 after the Union defeat at Bull Amunity of Lake d’Evere- lin Hills Bulletin, a local newsletter Run, near the present-day location ux is highlighted by the Belvale for the community off Richmond Civil War of Mount Eagle school in an area House. Belvale is a historic struc- Highway. known as Ballenger’s Hill. Since it ture that dates back to 1764, and According to a 1970 Histor- Rages On was on the highest point around, is rumored to have a ghost lurking ic American Buildings Survey As Telegraph Road leads toward the fort overlooked Telegraph on the grounds. -

Asv-Annual-Meeting-Program-2017

ARCHEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF VIRGINIA 77th ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2017 NATURAL BRIDGE HISTORIC HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER NATURAL BRIDGE, VIRGINIA 1 Welcome from ASV President Dear ASV Members and Guests, Coming Soon…. Enjoy our meeting! Carole Nash, President 2 Archeological Society of Virginia Officers President: Carole L. Nash Vice-President: Forrest Morgan (Massanutten Chapter) (Middle Peninsula Chapter) Secretary: Stephanie Jacobe Treasurer: Carl Fischer (Northern Virginia Chapter) (Middle Peninsula Chapter) Recent-Past President: Elizabeth Moore (Patrick Henry Chapter) Quarterly Bulletin Editor: Thane Harpole Web Master: Lyle Browning (Middle Peninsula Chapter) (Col Howard MacCord Chapter) Newsletter Editor: E. Randolph Turner (Nansemond Chapter) Arrangements Chair: Mike Barber (Eastern Shore Chapter) Program Chair: Dave Brown (Middle Peninsula Chapter) Hotel Logistics Registration: TBD Book Room: TBD Meeting Rooms: TBD 3 Note to Presenters and Moderators: Please closely adhere to the 20-minute limit on papers presentations. In addition, please show up for the session at least 10 minutes prior to its onset to load power points. Note: Authors enrolled in the Student Papers Competition are marked with a *. ARCHEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF VIRGINIA: 77th ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2017 NATURAL BRIDGE HISTORIC HOTEL & CONFERENCE CENTER NATURAL BRIDGE, VIRGINIA DRAFT AGENDA Thursday evening, October 26, 2017 7:30 Archaeology, Education, and Outreach Informal Session The Annual Meeting will begin informally on Thursday, October 26 at 7:30 p.m. with a session on ASV outreach and education at the K-12 level. The goals of this moderated session are to gauge interest in promoting archaeology to a younger audience and to learn from each other about programming ideas that work. -

Site Report: Traum 1323 Wilkes

Documentary Study and Archaeological Evaluation for 1323 Wilkes Street and 421 S. Payne Street Alexandria, Virginia prepared for Capital Investment Advisors Alexandria, Virginia prepared by JMA, A CCRG Company Alexandria, Virginia April 2015 DOCUMENTARY STUDY AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION FOR 1323 WILKES STREET AND 421 S. PAYNE STREET ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA Prepared for Capital Investment Advisors 800 Slaters Lane Alexandria, VA 22314 By Sarah Traum And Charles E. Goode, RPA JMA, A CCRG COMPANY 5250 Cherokee Avenue, Suite 300 Alexandria, Virginia 22312 (703) 354-9737 April 2015 ABSTRACT ABSTRACT The two parcels at 1323 Wilkes Street and 421 South Payne Street, Alexandria, Virginia have been proposed for redevelopment. The parcels consist of a mid-twentieth century warehouse and two-story office building with no vegetated open space area. Alexandria Archaeology reviewed the proposed project and determined that because the existing warehouse complex was built with a slab foundation, there is potential for archaeological deposits under the extant foundations. They concluded that the parcels may have the potential to contain significant archaeological deposits associated with the nearby Civil War U.S. Military Railroad Yard (no longer extant). JMA (a CCRG Company) prepared a documentary study of the two contiguous parcels in September 2014. The study included background research on the prehistory and history of the project area and its vicinity. Based on its findings, Alexandria Archaeology determined that there was potential for archaeological deposits associated with the stockade that protected the Civil War U.S. Military Railroad Yard. JMA then performed an archaeological evaluation within the warehouse to determine whether remains of the stockade are present below the concrete slab foundation. -

Alexandria Gazette Packet 25 Cents Vol

Alexandria Gazette Packet 25 Cents Vol. CCXXVI, No. 19 Serving Alexandria for over 200 years • A Connection Newspaper May 13, 2010 Transforming T.C. Call Off the Fireworks High school gets new principal as it Tight economy prompts nonprofits to examine creates vision for the future. their priorities and thin their calendars. By Michael Lee Pope model, and I’m Gazette Packet By Michael Lee Pope convinced that’s Gazette Packet why we made uring her second year as [adequate yearly principal at Seneca Valley progress].” emember the Water- D High School in Students with Suzanne front Festival? You Germantown, Md., Suzanne disabilities pose Maxey know, that annual R Maxey decided to do something one of the biggest event that’s hap- radical. Instead of segregating all challenges at T.C. Williams, where pened every year since 1981? the students with disabilities into students in this category consis- The one that involves entertain- special education classes, she de- tently have the lowest pass rates ment and fireworks the week- cided to integrate them with the of any group. But that’s only one end before Father’s Day? The general population. The idea was of the challenges. Students with one you’re still saving your left- a departure from the “self-con- economic disadvantages haven’t over beer tickets for? Well for- tained model” that was currently met federal standards in math for get about it. The Red Cross has in place at the school. Soon the last three years. Pass rates for cancelled the Waterfront Festi- enough, the school was meeting students with a limited grasp of val this year, and it’s doubtful federal standards under No Child the English language have been the festival will ever return. -

TAW Dec 17/Jan 18

February/March 2018 ® Volume 33, No. 2 The official newspaper of the American Volkssport Association — AVA: America’s Walking Club. Inside The Big Give, March 22 — President’s Message . 2 New AVA stamps . .5 Your chance to make a difference 401K Program . .5, 36 By Nancy Wittenberg Tips . 9 Regions . 6-16, 21-24 n March 22, much earlier than we have all personally benefited from last year, the AVA will again AVA through our participation. New elementary school programs. join San Antonio and sur- rounding counties in The Big Give For AVA this is a nation-wide experi- Page 4 OS.A., a 24-hour day of giving. The ence. Last year individuals, clubs and Big Give is AVA’s only annual fund state associations came together to raising campaign. Because it connects raise nearly $68,000. The people to the causes that matter the December/January edition of The most to them, AVA is counting on all American Wanderer on page 3 listed of us to connect with AVA through a AVA’s significant accomplishments donation to the Big Give. I know our this past year due in large part to all of cause, our mission, is one that matters us – 393 individuals and 92 clubs who to us all. Because our clubs promote donated through The Big Give. This OptOutside photos. and organize non-competitive physi- year our goal is $70,000. We are look- Pages 17-20, 35, 36 cal fitness activities that encourage ing for 450 individuals and 100 clubs lifelong fun, fitness and friendship, to help us reach that goal. -

Gazette Packet Alexandria

AlexandriaAlexandria Gazette Packet vokevoke ArtsArts ❖❖ EntertainmentEntertainment ❖❖ LeisureLeisure Art in the Area Calendar, Page 4 Local Eateries Food & Drink, Page 2 JazzyJazzy DayDay Enjoy the 31st annual Memorial Toast of Time Day Jazz Festival. Outdoors, Page 2 Outdoors,Outdoors Page,Page 3 Alexandria Gazette Packet ❖ May 15-21, 2008 ❖ 1E Food & Drink Around Town Historic Tours On Sunday May 18 from 2-4 p.m., en- joy this twice-a-year opportunity to visit What’s In A Name? Historic Huntley, 6918 Harrison Lane, a Federal-style unrestored villa built in Alexandria restaurateurs explain the names of their eateries. 1825 for Thomson Francis Mason, a grandson of George Mason. Children of By Julia O’Donoghue is named after the original location in Phila- opened in 1935 but she does know that the all ages will enjoy the puppet show fea- The Gazette delphia, which was opened by Samuel and name has stayed with the restaurant turing Thomson Francis Mason and Sarah Bookbinder in 1865 to feed through several owners. some of his family. Free Admission. Rain aming their business is one of watermen. “I don’t have a lot of research but they or shine. Light refreshments. 703-768- the most important decisions “It has become a Philadelphia tradition say it was because they had cedar trees 2525. Na restaurant owner makes. and we are carrying on that name,” said around it. There are still a couple of cedar When picking a name, many Whitcomb. trees but they are old. There are not a lot of School Art take into consideration where it would fall He added that he was unsure if the Book- trees like their used to be,” she said. -

Alexandria Library, Special Collections Subject Index to Northern Virginia History Magazines

Alexandria Library, Special Collections Subject Index to Northern Virginia History Magazines SUBJECT TITLE MAG DATE VOL ABBEY MAUSOLEUM LAND OF MARIA SYPHAX & ABBEY MAUSOLEUM AHM OCT 1984 VOL 7 #4 ABINGDON ABINDGON MANOR RUINS: FIGHT TO SAVE AHM OCT 1996 V 10 #4 ABINGDON OF ALEXANDER HUNTER, ET. AL. AHM OCT 1999 V 11 #3 AMONG OUR ARCHIVES AHM OCT 1979 VOL 6 #3 ARLINGTON'S LOCAL & NATIONAL HERITAGE AHM OCT 1957 VOL 1 #1 LOST HERITAGE: EARLY HOMES THAT HAVE DISAPPEARED NVH FEB 1987 VOL 9 #1 VIVIAN THOMAS FORD, ABINGDON'S LAST LIVING RESIDENT AHM OCT 2003 V 12 #3 ABOLITION SAMUEL M. JANNEY: QUAKER CRUSADER NVH FEB 1981 VOL 3 #3 ADAMS FAMILY SOME 18TH CENTURY PROFILES, PT. 1 AHM OCT 1977 VOL 6 #1 AESCULAPIAN HOTEL HISTORY OF SUNSET HILLS FARM FHM 1958-59 VOL 6 AFRICAN-AMERICANS BLACK HISTORY IN FAIRFAX COUNTY FXC SUM 1977 VOL 1 #3 BRIEF HISTORY & RECOLLECTIONS OF GLENCARLYN AHM OCT 1970 VOL 4 #2 DIRECTOR'S CHAIR (GUM SPRINGS) AAVN JAN 1988 VOL 6 #1 GUM SPRINGS COMMUNITY FXC SPR 1980 VOL 4 #2 GUM SPRINGS: TRIUMPH OF BLACK COMMUNITY FXC 1989 V 12 #4 NEW MT. VERNON MEMORIAL: MORE THAN GW'S SLAVES FXC NOV 1983 VOL 7 #4 SOME ARL. AREA PEOPLE: THEIR MOMENTS & INFLUENCE AHM OCT 1970 VOL 4 #1 SOME BLACK HISTORY IN ARLINGTON COUNTY AHM OCT 1973 VOL 5 #1 UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ADVISORY COM. MEETING AAVN FEB 1995 V 13 #2 AFRICAN-AMERICANS-ALEXANDRIA ARCHAEOLOGY OF ALEXANDRIA'S QUAKER COMMUNITY AAVN MAR 2003 V 21 #2 AFRICAN-AMERICANS-ARCHAEOLOGY BLACK BAPTIST CEMETERY ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVEST AAVN AUG 1991 VOL 9 #8 CEMETERY DISCOVERIES AAVN FEB 1992 V 10 #2 -

Newcomers & Community Guide

Newcomers & Community Guide 2019-2020 Springfield Days’ Card- board Boat Regatta at Lake Accotink Park. Photo contributed Photo Local Media Connection LLC online at www.connectionnewspapers.com New Movement & Acting Classes! Ages 4 - 12 Now Registering for Fall www.actheatre.com 2 ❖ Springfield Connection ❖ Newcomers & Community Guide 2019-20 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Newcomers Photo contributed Photo Peterson’s Ice Cream in Historic Town of Clifton. Photo contributed Photo Exciting New Developments From nationally ranked parks, fine Springfield Town Center restaurants, and shopping there is A Diverse and something for everyone in Springfield. By Pat Herrity improvements that will help to get you Supervisor - home to your families. Springfield Welcoming Community District Top Ten ginia Railway Express (VRE). You may also Exciting projects want to try using one of the many Metro pringfield Dis- My top 10 favorite places in the Dis- bus routes that serve our area, in addition Strict encom- trict (it’s hard to pick just 10): taking place to riding the Metro. passes every- thing from the his- 1. Burke Lake Park was named across Lee District. THERE ARE SOME WONDERFUL toric town of Clifton, to the bustling “Best Public Park” by NoVA magazine in PLACES to visit in Lee District. If you’re in shops of Fair Oaks Mall, to miles of trails 2018 and is the most visited park in By Jeffrey C. at beautiful Burke Lake Park. Our district Fairfax County’s Park system. The park the mood for shopping, don’t miss the McKay offers a variety of attractions for the contains a trail that goes around the lake Springfield Town Center. -

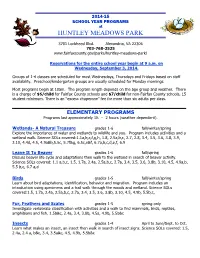

Huntley Meadows Elementary Programs

2014-15 SCHOOL YEAR PROGRAMS at HUNTLEY MEADOWS PARK 3701 Lockheed Blvd. Alexandria, VA 22306 703-768-2525 www.fairfaxcounty.gov/parks/huntley-meadows-park/ Reservations for the entire school year begin at 9 a.m. on Wednesday, September 3, 2014. Groups of 1-4 classes are scheduled for most Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays based on staff availability. Preschool/kindergarten groups are usually scheduled for Monday mornings. Most programs begin at 10am. The program length depends on the age group and weather. There is a charge of $6/child for Fairfax County schools and $7/child for non-Fairfax County schools, 15 student minimum. There is an “excess chaperone” fee for more than six adults per class. ELEMENTARY PROGRAMS Programs last approximately 1½ - 2 hours (weather dependent). Wetlands- A Natural Treasure grades 1-6 fall/winter/spring Explore the importance of water and wetlands to wildlife and you. Program includes activities and a wetland walk. Science SOLs covered:1.1a,b,c,f,g,h, 1.8, 2.5a,b,c, 2.7, 2.8, 3.4, 3.5, 3.6, 3.8, 3.9, 3.10, 4.4d, 4.5, 4.9a&b,5.5c, 5.7f&g, 6.5c,e&f, 6.7a,b,c,d,e,f, 6.9 Leave It To Beaver grades 1-6 fall/spring Discuss beaver life cycle and adaptations then walk to the wetland in search of beaver activity. Science SOLs covered: 1.1 a,b,c, 1.5, 1.7a, 2.4a, 2.5a,b,c, 2.7a, 3.4, 3.5, 3.6, 3.8b, 3.10, 4.5, 4.9a,b, 5.5 b,c, 6.7 a,d Birds grades 1-5 fall/winter/spring Learn about bird adaptations, identification, behavior and migration. -

Notes on Huntley Meadows Park By

Notes on Huntley Meadows Park By: David L. Gorsline 6 April 2009 revised 27 April 2009 Copyright (c) 2009 David L. Gorsline All rights reserved Prepared for: Introduction to Ecology, NATH 1160 Gary Evans Introduction Huntley Meadows Park comprises approximately 1,425 acres (577 ha) of freshwater wetland and surrounding forest in southern Fairfax County, Virginia. Managed by the Fairfax County Park Authority (FCPA), it is the County's largest park, and features the largest (70+ acres, 28+ ha) non- tidal marsh in the area. Bounded by housing subdivisions to the north, east, and south, and government installations to the west and southwest, the Park is an island of blue and green prized by casual strollers and scientific specialists alike. It is particularly valued by naturalists for the unique diversity of the habitat to be found there, especially considering its urban/suburban surroundings. Guidebook writers and editors like Scott Weidensaul [Weidensaul92] and David W. Johnston [Johnston97] have singled out the Park for special attention, noting that its mix of woods and water makes it a popular spot for Big Day birders; Weidensaul calls the Park's very existence "utterly improbable," encroached on as it is by the busy traffic corridors of U.S. 1 and Interstates 95 and 495. The main entrance to Huntley Meadows Park is only three miles from the Huntington terminus of Metro's Yellow Line, and hence the Park is a short trip from anywhere in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. General Environment and Setting The Park is situated in the Atlantic Coastal Plain province at approximately 38° 45′ N latitude and 77° 06′ W longitude at about 10 m in elevation. -

Historic Huntley General Management Plan

FAIRFAX COUNTY PARK AUTHORITY FEBRUARY 2002 Approved 2/27/02 Historic Huntley General Management Plan HISTORIC HUNTLEY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS GENERAL MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR HISTORIC HUNTLEY FAIRFAX COUNTY PARK AUTHORITY January 2002 Park Authority Board Winifred S. Shapiro, Chairman, Braddock District Gilbert S. McCutcheon, Vice Chairman, Mt. Vernon District Jennifer E. Heinz, Secretary, At-Large Kenneth G. Feng, Treasurer, Springfield District Harold Henderson, Lee District Joanne E. Malone, Providence District Gwendolyn L. Minton, Hunter Mill District Phillip A. Niedzielski-Eichner, At-Large Harold L. Strickland, Sully District Richard C. Thoesen, Dranesville District Frank S. Vajda, Mason District Senior Staff Paul L. Baldino, Director Michael A. Kane, Deputy Director Cindy Messinger, Director, Park Services Division Miriam C. Morrison, Director, Administration Division Judith Pedersen, Public Information Officer Lee D. Stephenson, Director, Resource Management Division Lynn S. Tadlock, Director, Planning & Development Division Timothy K. White, Director, Park Operations Division Task Force Planning Team Barbara Ballentine Carolyn Gamble Susan Escherich Karen Lindquist Jere Gibber Barbara Naef Erica Hershler Joseph Nilson Norma Hoffman Todd Roberts Lisa Holt Gary Roisum Laura Martin Richard Sacchi Robbie McNeil P AGE 2 HISTORIC HUNTLEY TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms/Terms ................................................................................................. 4 I. INTRODUCTION A. Purpose and Description of the Plan............................................................ -

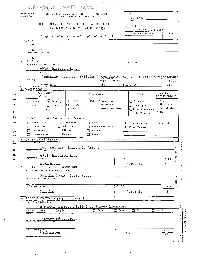

Nomination Form for Nps Use Only

1L_gFscgp-?Gy, I (Chock One) (1 EIII 1 God (11J Feic I Deed EJ Ruins I1 Unniposod CONDITION .. -- (Chrrk On") (Chock On.) [;IAII~,C~ I unotterad n MOV-~ ,-s O.~~,~OIsite -_ ~d--- THE 1PRCSENT ANO ORIGINAL (11 LnolvnJ PHYSICAL ~PPEARANCE Facing south from its knoll across fieldswhich decline in three terraces the mansion house at Huntley and its si~rroundingfarm complex were built around 1820 in the architectural style of the Early Federal Period. Originally constructed in the shape of an "H" with the central bar rising to three storics on the south and two on the north, the main house is built of brick laid in common bond. The flanking wings which are one story lower than the one-room central section are comprised of two rooms. The regularity of design on both the front and the rear has been achieved by the use of a full basement which serves to compensate for the uneven grade of the hill. From the front the broad central gable is crowned by two rec- tangular interior chimneys which run parallel to the roofline. The central gable which was once clipped, giving the impression of a hipped roof, is lighted by three bays with casements of nine panes each. Today the gable peak addition is hidden by shingle siding which fills the resulting pediment. The second story of the central section is topped by a mousetooth brick cor- m nice that once marked the edge of the clipped roof. The first floor central rn section is sheltered by a three-bay porch addition that links the pedimented rn wings.