^Pianos Inthe Smithsonian ^Nstitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

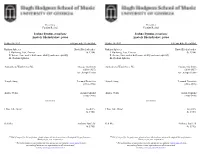

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång Till

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång till Lotta, Jan Sandström. Edition Tarrodi: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. Trombone and piano. Requires modest range (F – g flat1), well-developed lyricism, and musicianship. There are two versions of this piece, this and another that is scored a minor third higher. Written dynamics are minimal. Although phrases and slurs are not indicated, it is a SONG…encourage legato tonguing! Stephan Schulz, bass trombonist of the Berlin Philharmonic, gives a great performance of this work on YouTube - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mn8569oTBg8. A Winter’s Night, Kevin McKee, 2011. Available from the composer, www.kevinmckeemusic.com. Trombone and piano. Explores the relative minor of three keys, easy rhythms, keys, range (A – g1, ossia to b flat1). There is a fine recording of this work on his web site. Trombone Sonata, Gordon Jacob. Emerson Edition: Yorkshire, England, 1979. Trombone and piano. There are no real difficult rhythms or technical considerations in this work, which lasts about 7 minutes. There is tenor clef used throughout the second movement, and it switches between bass and tenor in the last movement. Range is F – b flat1. Recorded by Dr. Ron Babcock on his CD Trombone Treasures, and available at Hickey’s Music, www.hickeys.com. Divertimento, Edward Gregson. Chappell Music: London, 1968. Trombone and piano. Three movements, range is modest (G-g#1, ossia a1), bass clef throughout. Some mixed meter. Requires a mute, glissandi, and ad. lib. flutter tonguing. Recorded by Brett Baker on his CD The World of Trombone, volume 1, and can be purchased at http://www.brettbaker.co.uk/downloads/product=download-world-of-the- trombone-volume-1-brett-baker. -

Working List of Repertoire for Tenor Trombone Solo and Bass Trombone Solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers

Working List of Repertoire for tenor trombone solo and bass trombone solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers Working list v.2.4 ~ May 30, 2021 Prepared by Douglas Yeo, Guest Lecturer of Trombone Wheaton College Conservatory of Music Armerding Center for Music and the Arts www.wheaton.edu/conservatory 520 E. Kenilworth Avenue Wheaton, IL 60187 Email: [email protected] www.wheaton.edu/academics/faculty/douglas-yeo Works by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) Composers: Tenor trombone • Amis, Kenneth Preludes 1–5 (with piano) www.kennethamis.com • Barfield, Anthony Meditations of Sound and Light (with piano) Red Sky (with piano/band) Soliloquy (with trombone quartet) www.anthonybarfield.com 1 • Baker, David Concert Piece (with string orchestra) - Lauren Keiser Publishing • Chavez, Carlos Concerto (with orchestra) - G. Schirmer • Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel (arr. Ralph Sauer) Gypsy Song & Dance (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • DaCosta, Noel Four Preludes (with piano) Street Calls (unaccompanied) • Davis, Nathaniel Cleophas (arr. Aaron Hettinga) Oh Slip It Man (with piano) Mr. Trombonology (with piano) Miss Trombonism (with piano) Master Trombone (with piano) Trombone Francais (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • John Duncan Concerto (with orchestra) Divertimento (with string quartet) Three Proclamations (with string quartet) library.umkc.edu/archival-collections/duncan • Hailstork, Adolphus Cunningham John Henry’s Big (Man vs. Machine) (with piano) - Theodore Presser • Hong, Sungji Feromenis pnois (unaccompanied) • Lam, Bun-Ching Three Easy Pieces (with electronics) • Lastres, Doris Magaly Ruiz Cuasi Danzón (with piano) Tres Piezas (with piano) • Ma, Youdao Fantasia on a Theme of Yada Meyrien (with piano/orchestra) - Jinan University Press (ISBN 9787566829207) • McCeary, Richard Deming Jr. -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

Portable Digital Musical Instruments 2009 — 2010

PORTABLE DIGITAL MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS 2009 — 2010 music.yamaha.com/homekeyboard For details please contact: This document is printed with soy ink. Printed in Japan How far do you want What kind of music What are your Got rhythm? to go with your music? do you want to play? creative inclinations? Recommended Recommended Recommended Recommended Tyros3 PSR-OR700 NP-30 PSR-E323 EZ-200 DD-65 PSR-S910 PSR-S550B YPG series PSR-E223 PSR-S710 PSR-E413 Pages 4-7 Pages 8-11 Pages 12-13 Page 14 The sky's the limit. Our Digital Workstations are jam-packed If the piano is your thing, Yamaha has a range of compact We've got Digital Keyboards of all types to help players of every If drums and percussion are your strong forte, our Digital with advanced features, exceptionally realistic sounds and piano-oriented instruments that have amazingly realistic stripe achieve their full potential. Whether you're just starting Percussion unit gives you exceptionally dynamic and expressive performance functions that give you the power sound and wonderfully expressive playability–just like having out or are an experienced expert, our instrument lineup realistic sounds, letting you pound out your own beats–in to create, arrange and perform in any style or situation. a real piano in your house, with a fraction of the space. provides just what you need to get your creative juices flowing. live performance, in rehearsal or in recording. 2 3 Yamaha’s Premier Music Workstation – Unsurpassed Quality, Features and Performance Ultimate Realism Limitless Creative Potential Interactive -

The World Atlas of Musical Instruments

Musik_001-004_GB 15.03.2012 16:33 Uhr Seite 3 (5. Farbe Textschwarz Auszug) The World Atlas of Musical Instruments Illustrations Anton Radevsky Text Bozhidar Abrashev & Vladimir Gadjev Design Krassimira Despotova 8 THE CLASSIFICATION OF INSTRUMENTS THE STUDY OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS, their history, evolution, construction, and systematics is the subject of the science of organology. Its subject matter is enormous, covering practically the entire history of humankind and includes all cultural periods and civilizations. The science studies archaeological findings, the collections of ethnography museums, historical, religious and literary sources, paintings, drawings, and sculpture. Organology is indispensable for the development of specialized museum and amateur collections of musical instruments. It is also the science that analyzes the works of the greatest instrument makers and their schools in historical, technological, and aesthetic terms. The classification of instruments used for the creation and performance of music dates back to ancient times. In ancient Greece, for example, they were divided into two main groups: blown and struck. All stringed instruments belonged to the latter group, as the strings were “struck” with fingers or a plectrum. Around the second century B. C., a separate string group was established, and these instruments quickly acquired a leading role. A more detailed classification of the three groups – wind, percussion, and strings – soon became popular. At about the same time in China, instrument classification was based on the principles of the country’s religion and philosophy. Instruments were divided into eight groups depending on the quality of the sound and on the material of which they were made: metal, stone, clay, skin, silk, wood, gourd, and bamboo. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

Marquetry on Drawer-Model Marionette Duo-Art

Marquetry on Drawer-Model Marionette Duo-Art This piano began life as a brown Recordo. The sound board was re-engineered, as the original ribs tapered so soon that the bass bridges pushed through. The strings were the wrong weight, and were re-scaled using computer technology. Six more wound-strings were added, and the weights of the steel strings were changed. A 14-inch Duo-Art pump, a fan-expression system, and an expression-valve-size Duo-Art stack with a soft-pedal compensation lift were all built for it. The Marquetry on the side of the piano was inspired by the pictures on the Arto-Roll boxes. The fallboard was inspired by a picture on the Rhythmodic roll box. A new bench was built, modeled after the bench originally available, but veneered to go with the rest of the piano. The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 42, NUMBER 5 Teresa Carreno (1853-1917) ISSN #1533-9726 THE AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION Published by the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association, a non-profit, tax exempt group devoted to the restoration, distribution and enjoyment of musical instruments using perforated paper music rolls and perforated music books. AMICA was founded in San Francisco, California in 1963. PROFESSOR MICHAEL A. KUKRAL, PUBLISHER, 216 MADISON BLVD., TERRE HAUTE, IN 47803-1912 -- Phone 812-238-9656, E-mail: [email protected] Visit the AMICA Web page at: http://www.amica.org Associate Editor: Mr. Larry Givens VOLUME 42, Number -

Piano Manufacturing an Art and a Craft

Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Gesa Lücker (Concert pianist and professor of piano, University for Music and Drama, Hannover) Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Since time immemorial, music has accompanied mankind. The earliest instrumentological finds date back 50,000 years. The first known musical instrument with fibers under ten sion serving as strings and a resonator is the stick zither. From this small beginning, a vast array of plucked and struck stringed instruments evolved, eventually resulting in the first stringed keyboard instruments. With the invention of the hammer harpsichord (gravi cembalo col piano e forte, “harpsichord with piano and forte”, i.e. with the capability of dynamic modulation) in Italy by Bartolomeo Cristofori toward the beginning of the eighteenth century, the pianoforte was born, which over the following centuries evolved into the most versitile and widely disseminated musical instrument of all time. This was possible only in the context of the high level of devel- opment of artistry and craftsmanship worldwide, particu- larly in the German-speaking part of Europe. Since 1885, the Schimmel family has belonged to a circle of German manufacturers preserving the traditional art and craft of piano building, advancing it to ever greater perfection. Today Schimmel ranks first among the resident German piano manufacturers still owned and operated by Contents the original founding family, now in its fourth generation. Schimmel pianos enjoy an excellent reputation worldwide. 09 The Fascination of the Piano This booklet, now in its completely revised and 15 The Evolution of the Piano up dated eighth edition, was first published in 1985 on The Origin of Music and Stringed Instruments the occa sion of the centennial of Wilhelm Schimmel, 18 Early Stringed Instruments – Plucked Wood Pianofortefa brik GmbH. -

Italian Harpsichord-Building in the 16Th and 17Th Centuries by John D

Italian Harpsichord-Building in the 16th and 17th Centuries by John D. Shortridge (REPRINTED WITH CHANGES—1970) CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND TECHNOLOGY UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 225 · Paper 15, Pages 93–107 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS · WASHINGTON, D.C. · 1970 Figure 1.—OUTER CASE OF ALBANA HARPSICHORD. Italian Harpsichord-Buildingin the 16th and 17th Centuries By John D. Shortridge The making of harpsichords flourished in Italy throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. The Italian instruments were of simpler construction than those built by the North Europeans, and they lacked the familiar second manual and array of stops. In this paper, typical examples of Italian harpsichords from the Hugo Worch Collection in the United States National Museum are described in detail and illustrated. Also, the author offers an explanation for certain puzzling variations in keyboard ranges and vibrating lengths of strings of the Italian harpsichords. THE AUTHOR: John D. Shortridge is associate curator of cultural history in the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution. PERHAPS the modern tendency to idealize progress has been responsiblefor the neglect of Italian harpsichords and virginals during the present day revival of interest in old musical instruments. Whatever laudable traits the Italian builders may have had, they cannot be considered to have been progressive. Their instruments of the mid-16th century hardly can be distinguished from those made around 1700. During this 150 years the pioneering Flemish makers added the four-foot register, a second keyboard, and lute and buff stops to their instruments. However, the very fact that the Italian builders were unwilling to change their models suggests that their instruments were good enough to demand no further improvements. -

The American Bach Society the Westfield Center

The Eastman School of Music is grateful to our festival sponsors: The American Bach Society • The Westfield Center Christ Church • Memorial Art Gallery • Sacred Heart Cathedral • Third Presbyterian Church • Rochester Chapter of the American Guild of Organists • Encore Music Creations The American Bach Society The American Bach Society was founded in 1972 to support the study, performance, and appreciation of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach in the United States and Canada. The ABS produces Bach Notes and Bach Perspectives, sponsors a biennial meeting and conference, and offers grants and prizes for research on Bach. For more information about the Society, please visit www.americanbachsociety.org. The Westfield Center The Westfield Center was founded in 1979 by Lynn Edwards and Edward Pepe to fill a need for information about keyboard performance practice and instrument building in historical styles. In pursuing its mission to promote the study and appreciation of the organ and other keyboard instruments, the Westfield Center has become a vital public advocate for keyboard instruments and music. By bringing together professionals and an increasingly diverse music audience, the Center has inspired collaborations among organizations nationally and internationally. In 1999 Roger Sherman became Executive Director and developed several new projects for the Westfield Center, including a radio program, The Organ Loft, which is heard by 30,000 listeners in the Pacific 2 Northwest; and a Westfield Concert Scholar program that promotes young keyboard artists with awareness of historical keyboard performance practice through mentorship and concert opportunities. In addition to these programs, the Westfield Center sponsors an annual conference about significant topics in keyboard performance. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J.