Applying an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior for Sustaining a Landscape Restaurant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

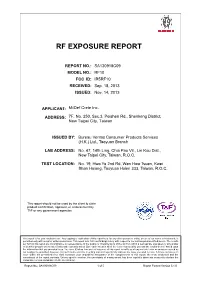

Fcc Test Report

RF EXPOSURE REPORT REPORT NO.: SA130918C09 MODEL NO.: RF10 FCC ID: IR5RF10 RECEIVED: Sep. 18, 2013 ISSUED: Nov. 14, 2013 APPLICANT: MilDef Crete Inc. ADDRESS: 7F, No. 250, Sec.3, Peishen Rd., Shenkeng District, New Taipei City, Taiwan ISSUED BY: Bureau Veritas Consumer Products Services (H.K.) Ltd., Taoyuan Branch LAB ADDRESS: No. 47, 14th Ling, Chia Pau Vil., Lin Kou Dist., New Taipei City, Taiwan, R.O.C. TEST LOCATION: No. 19, Hwa Ya 2nd Rd, Wen Hwa Tsuen, Kwei Shan Hsiang, Taoyuan Hsien 333, Taiwan, R.O.C. This report should not be used by the client to claim product certification, approval, or endorsement by TAF or any government agencies. This report is for your exclusive use. Any copying or replication of this report to or for any other person or entity, or use of our name or trademark, is permitted only with our prior written permission. This report sets forth our findings solely with respect to the test samples identified herein. The results set forth in this report are not indicative or representative of the quality or characteristics of the lot from which a test sample was taken or any similar or identical product unless specifically and expressly noted. Our report includes all of the tests requested by you and the results thereof based upon the information that you provided to us. You have 60 days from date of issuance of this report to notify us of any material error or omission caused by our negligence, provided, however, that such notice shall be in writing and shall specifically address the issue you wish to raise. -

List of Insured Financial Institutions (PDF)

401 INSURED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS 2021/5/31 39 Insured Domestic Banks 5 Sanchong City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 62 Hengshan District Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 1 Bank of Taiwan 13 BNP Paribas 6 Banciao City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 63 Sinfong Township Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 2 Land Bank of Taiwan 14 Standard Chartered Bank 7 Danshuei Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 64 Miaoli City Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 3 Taiwan Cooperative Bank 15 Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation 8 Shulin City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 65 Jhunan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 4 First Commercial Bank 16 Credit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 9 Yingge Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 66 Tongsiao Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 5 Hua Nan Commercial Bank 17 UBS AG 10 Sansia Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 67 Yuanli Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 6 Chang Hwa Commercial Bank 18 ING BANK, N. V. 11 Sinjhuang City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 68 Houlong Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 7 Citibank Taiwan 19 Australia and New Zealand Bank 12 Sijhih City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 69 Jhuolan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 8 The Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank 20 Wells Fargo Bank 13 Tucheng City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 70 Sihu Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 9 Taipei Fubon Commercial Bank 21 MUFG Bank 14 -

台灣鄉鎮名中英對照 2 Page 7 Pt Bilingual Taiwantwnship Names__For Church Data Maps

台灣鄉鎮名中英對照 2 page 7 pt Bilingual TaiwanTwnship Names__For Church Data Maps Bilingual Names For 46. Taishan District 泰山區 93. Cholan Town 卓蘭鎮 142. Fenyuan Twnship 芬園鄉 Taiwan Cities, Districts, 47. Linkou District 林口區 94. Sanyi Township 三義鄉 143. Huatan Township 花壇鄉 Towns, and Townships 48. Pali District 八里區 95. Yuanli Town 苑裏鎮 144. Lukang Town 鹿港鎮 For Church Distribution Maps 145. Hsiushui Twnship 秀水鄉 Taoyuan City 桃園市 Taichung City 台中市 146. Tatsun Township 大村鄉 49. Luchu Township 蘆竹區 96. Central District 中區 147. Yuanlin Town 員林鎮 Taipei City 台北市 50. Kueishan Twnship 龜山區 97. North District 北區 148. Shetou Township 社頭鄉 1. Neihu District 內湖區 51. Taoyuan City 桃園區 98. West District 西區 149. YungchingTnshp 永靖鄉 2. Shihlin District 士林區 52. Pate City 八德區 99. South District 南區 150. Puhsin Township 埔心鄉 3. Peitou District 北投區 53. Tahsi Town 大溪區 100. East District 東區 151. Hsihu Town 溪湖鎮 4. Sungshan District 松山區 54. Fuhsing Township 復興區 101. Peitun District 北屯區 152. Puyen Township 埔鹽鄉 5. Hsinyi District 信義區 55. Lungtan Township 龍潭區 102. Hsitun District 西屯區 153. Fuhsing Twnship 福興鄉 6. Taan District 大安區 56. Pingchen City 平鎮區 103. Nantun District 南屯區 154. FangyuanTwnshp 芳苑鄉 7. Wanhua District 萬華區 57. Chungli City 中壢區 104. Taan District 大安區 155. Erhlin Town 二林鎮 8. Wenshan District 文山區 58. Tayuan District 大園區 105. Tachia District 大甲區 156. Pitou Township 埤頭鄉 9. Nankang District 南港區 59. Kuanyin District 觀音區 106. Waipu District 外埔區 157. Tienwei Township 田尾鄉 10. Chungshan District 中山區 60. Hsinwu Township 新屋區 107. Houli District 后里區 158. Peitou Town 北斗鎮 11. -

Map of Grand Hotel

I Host and Co-hosted by: National Chia-Yi University National Taiwan Normal University National Chin-Yi University of Technology Washington State University Alexander Technological Institute of Thessaloniki Supervisory Organizers: National Science Council Partner University-Sponsors: National Changhua University of Education II Contents Conference Information .................................................................................................... - 1 - Venue ......................................................................................................................................... - 1 - Conference Theme ............................................................................................................... - 3 - Submission of Abstracts .................................................................................................... - 4 - AHTMMC 2013 Conference Committees .................................................................. - 5 - International Scientific Committee Members ....................................................... - 5 - Organizing Committee ...................................................................................................... - 8 - Co-Chair .................................................................................................................................. - 9 - Keynote Speaker ................................................................................................................ - 13 - Hotel Accommodation ................................................................................................... -

The Political Kiaesthetics of Contemporary Dance:—

The Political Kinesthetics of Contemporary Dance: Taiwan in Transnational Perspective By Chia-Yi Seetoo A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Miryam Sas, Chair Professor Catherine Cole Professor Sophie Volpp Professor Andrew F. Jones Spring 2013 Copyright 2013 Chia-Yi Seetoo All Rights Reserved Abstract The Political Kinesthetics of Contemporary Dance: Taiwan in Transnational Perspective By Chia-Yi Seetoo University of California, Berkeley Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies Professor Miryam Sas, Chair This dissertation considers dance practices emerging out of post-1980s conditions in Taiwan to theorize how contemporary dance negotiates temporality as a political kinesthetic performance. The dissertation attends to the ways dance kinesthetically responds to and mediates the flows of time, cultural identity, and social and political forces in its transnational movement. Dances negotiate disjunctures in the temporality of modernization as locally experienced and their global geotemporal mapping. The movement of performers and works pushes this simultaneous negotiation to the surface, as the aesthetics of the performances registers the complexity of the forces they are grappling with and their strategies of response. By calling these strategies “political kinesthetic” performance, I wish to highlight how politics, aesthetics, and kinesthetics converge in dance, and to show how political and affective economies operate with and through fully sensate, efforted, laboring bodies. I begin my discussion with the Cursive series performed by the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan, whose intersection of dance and cursive-style Chinese calligraphy initiates consideration of the temporal implication of “contemporary” as “contemporaneity” that underlies the simultaneous negotiation of local and transnational concerns. -

Welcome to the Central Bank of China

401 INSURED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS 2021/3/31 39 Insured Domestic Banks 5 Sanchong City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 62 Hengshan District Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 1 Bank of Taiwan 14 BNP Paribas 6 Banciao City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 63 Sinfong Township Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 2 Land Bank of Taiwan 15 Standard Chartered Bank 7 Danshuei Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 64 Miaoli City Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 3 Taiwan Cooperative Bank 16 Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation 8 Shulin City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 65 Jhunan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 4 First Commercial Bank 17 Credit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 9 Yingge Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 66 Tongsiao Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 5 Hua Nan Commercial Bank 18 UBS AG 10 Sansia Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 67 Yuanli Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 6 Chang Hwa Commercial Bank 19 ING BANK, N. V. 11 Sinjhuang City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 68 Houlong Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 7 Citibank Taiwan 20 Australia and New Zealand Bank 12 Sijhih City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 69 Jhuolan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 8 The Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank 21 Wells Fargo Bank 13 Tucheng City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 70 Sihu Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 9 Taipei Fubon Commercial Bank 22 MUFG Bank 14 -

To Meet Same-Day Flight Cut-Off Time and Cut-Off Time for Fax-In Customs Clearance Documents

Zip Same Day Flight No. Area Post Office Name Telephone Number Address Code Cut-off time* No. 114, Sec. 1, Jhongsiao W. Rd., Jhongjheng District, Taipei 100-12, Taiwan 1 Greater Taipei Taipei Beimen Post Office 100 (02)2361-5752(02)2381-3135 16:00 ( R.O.C.) 1F, No. 162, Sec. 1, Singsheng S. Rd., Jhongjheng District, Taipei 100-61, Taiwan 3 Greater Taipei Taipei Dongmen Post Office 100 (02)2394-7576(02)2321-4679 14:45 (R.O.C.) 4 Greater Taipei Taipei Nanhai Post Office 100 (02)2396-3142(02)2321-4189 No. 43, Sec. 2, Chongcing S. Rd., Jhongjheng District, Taipei 100-75, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 14:40 (02)2368-4714 5 Greater Taipei Taipei Yingciao Post Office 100 No. 76, Siamen St., Jhongjheng District, Taipei 100-83, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 14:50 (02)2367-0905 6 Greater Taipei Taipei Fusing BridgePost Office 100 (02)2311-4421 No. 1, Sec. 1, Jhongsiao W. Rd., Jhongjheng District, Taipei 100-41, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 15:35 7 Greater Taipei Executive Yuan Post Office 100 (02)2321-4874 No. 2, Beiping E. Rd., Jhongjheng District, Taipei 100-51, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 15:25 (02)2331-0962 8 Greater Taipei Academia Historica Post Office 100 No. 168-1, Bo-ai Rd., Jhongjheng District, Taipei 100-48, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 15:50 (02)2311-7879 No. 122, Sec. 1, Chongcing S. Rd., Jhongjheng District, Taipei 100-48, Taiwan 9 Greater Taipei Presidential Office Building Post Office 100 (02)2311-0859 D+1 (R.O.C.) (02)2331-4925 10 Greater Taipei Taipei District Court Post Office 100 No. -

Welcome to the Central Bank of China

400 INSURED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS 2017/7/31 39 Insured Domestic Banks 5 Sanchong City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 62 Hengshan District Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 1 Bank of Taiwan 13 BNP Paribas 6 Banciao City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 63 Sinfong Township Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 2 Land Bank of Taiwan 14 Standard Chartered Bank 7 Danshuei Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 64 Miaoli City Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 3 Taiwan Cooperative Bank 15 Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation Ltd. 8 Shulin City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 65 Jhunan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 4 First Commercial Bank 16 Credit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 9 Yingge Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 66 Tongsiao Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 5 Hua Nan Commercial Bank 17 UBS AG 10 Sansia Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 67 Yuanli Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 6 Chang Hwa Commercial Bank 18 ING BANK, N. V. 11 Sinjhuang City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 68 Houlong Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 7 Citibank (Taiwan) Limited 19 Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited 12 Sijhih City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 69 Jhuolan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 8 The Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank 20 Wells Fargo Bank, National Association 13 Tucheng City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 70 Sihu Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 9 Taipei Fubon Commercial Bank Co., Ltd. 21 The Bank Of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd. 14 Lujhou City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 71 Gongguan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 10 Cathay United Bank 22 Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation 15 Wugu Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 72 Tongluo Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 11 Bank of Kaohsiung 23 Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria S.A. -

New Taipei City Government

Environmental Protection Department New Taipei City Government ClimateNew Taipei Adaptation City Action Plan (Abridged Edition) HAZARD RISK CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION August 2015 I hereby declare the intent of the city of New Taipei to comply with the Com- pact of Mayors, the world’s largest cooperative effort among mayors and city leaders to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, track progress, and prepare for the impacts of climate change. The Compact of Mayors has defined a series of requirements that cities are expected to meet over time, recognizing that each city may be at a differ- ent stage of development on the pathway to compliance with the Com- pact. I commit to advancing the city of New Taipei along the stages of the Com- pact, with the goal of becoming fully compliant with all the requirements within three years. Specifically, I pledge to publicly report on the following within the next three years: •The greenhouse gas emissions inventory for our city consistent with the Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventories (GPC), within one year or less •The climate hazards faced by our city, within one year or less •Our target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, within two years or less •The climate vulnerabilities faced by our citiy, within two years or less •Our plans to address climate change mitigation and adaptation within three years of less Yours Faithfully, ■ CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 /Origin and Purpose1 CHAPTER 2 Hazard Identification 2 /New Taipei City Environmental Status 2 Hazard Identification Techniques -

Recreation and Tourism Service Systems Featuring High Riverbanks in Taiwan

water Article Recreation and Tourism Service Systems Featuring High Riverbanks in Taiwan Guey-Shin Shyu 1,* , Wei-Ta Fang 2 and Bai-You Cheng 3,* 1 Department of Tourism, Tungnan University, Shenkeng District, New Taipei City 22202, Taiwan 2 Graduate Institute of Environmental Education, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei City 11677, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Graduate Institute of Environmental Resources Management, TransWorld University, Douliu City, Yunlin County 64063, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.-S.S.); [email protected] (B.-Y.C.); Tel.: +886-2-8662-5958 (ext. 723) (G.-S.S.); +886-5-5370988 (ext. 8233) (B.-Y.C.) Received: 4 August 2020; Accepted: 3 September 2020; Published: 4 September 2020 Abstract: Taiwan’s cities exhibit high levels of urbanization, which has resulted in limited recreation space in urban areas. In response, government policies have been enacted to promote the large-scale greening of rivers in urban areas and the establishment of aquatic recreation areas that do not interfere with water flow areas, pavilions for recreation purposes, indoor stadiums, and biking lanes alongside riverbanks to provide citizens with recreation space. An expert team was convened to investigate 50 riverside recreation sites, and the Comfortable Water Environment Rest Assessment Form was devised. The investigation results revealed three factors that contribute to the value of riverside recreation sites; the three factors had a total explanatory power of 70.17%. The factors, namely exercising and leisure, overall design plan and entrance image, and environmental maintenance and service, had an explanatory power of 25.52%, 23.32%, and 21.32%, respectively. -

Annual Important Performance

Annual Important Performance Item Unit 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1.Capacity of Water Supply System M3/Day … … … … … … 2.Capacity of Water-Purification-Station M3/Day 1,552,559 1,802,000 2,439,390 2,731,112 2,921,834 3,187,036 3.Average Yield Per Day M3 1,176,321 1,265,741 1,332,205 1,513,115 1,791,415 1,996,937 4.Average Water Distributed Per Day M3 1,159,958 1,251,325 1,329,623 1,509,732 1,786,097 1,993,547 5.Average Water Sold Per Day M3 791,814 833,840 906,641 1,053,783 1,294,756 1,493,036 6.Yield M3 429,357,104 461,995,434 487,586,996 552,286,833 653,866,592 728,881,919 7.Distributed Water M3 423,384,502 456,733,547 486,641,970 551,052,131 651,925,230 727,644,563 8.Water Sold M3 289,012,366 304,351,457 331,830,538 384,630,881 472,585,950 544,957,993 9.Actual Meter-Readings M3 … … 325,943,007 366,487,228 447,447,054 508,369,477 10.Percentage of Water Sold % 68.26 66.64 68.19 69.80 72.49 74.89 11.Percentage of Actual Meter Readings % … … 66.98 66.51 68.63 69.87 12.Administrative Population Person 13,212,945 13,431,137 13,688,930 13,908,275 14,127,946 14,376,247 13.Designed Population Person 6,248,858 6,780,700 7,616,810 8,300,890 8,927,215 9,503,965 14. -

2014 Annual Report Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2014

2014 Annual Report Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2014 89, Sec. 6, Zhongshan N. Rd., Taipei 11155, Taiwan, R.O.C. Tel: (886) 2-2833-9999 Fax: (886) 2-2833-8833 www.ctci.com.tw Professionalism Integrity Teamwork Innovation VISION The Most Reliable Global Engineering Service Provider VISION The MostPRINCIPLES Reliable Global Professionalism Engineering ServiceIntegrity ProviderTeamwork Innovation PRINCIPLES Professionalism;MISSION To Satisfy Integrity; Our Teamwork;Customers with Innovation the Optimized Engineering Services MISSION To Satisfy Our Customers with the Optimized Engineering Services Contents 02 Financial Highlights 04 Company Profile 06 Letter from the Chairman & CEO 12 Milestones 2014 13 Strategy Development and Outlook 14 Strategic Operations I. Intelligent Engineering Services II. QHSE Management III. CTCI Group IT Integration IV. CTCI Talent and Leadership Optimization 28 Business Review & Outlook I. Hydrocarbon II. Infrastructure, Environment & Power III. Environment & Resources 43 Corporate Sustainability 49 Financial Section 67 Global Network FinancialFinancial Highlights Highlights Financial Highlights December 31, 2014 and 2013 Thousands of Thousands of NT$ US$ 2014 2013 2014 For the Year: Operating revenues $38,060,203 $31,446,326 $1,203,675 Net income 1,882,119 1,641,730 59,523 At Year-End: Total assets $41,144,103 $33,748,107 $1,301,205 Long-term debt - - - Total equity 17,137,716 16,472,113 541,990 Net income per common share: NT$2.51 NT$2.22 US$0.08 Contract Amount Backlog (Million NT$) (Million NT$) 20102010