The Colorado Plateau and Some Questions for Its Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Core Study Unearths Insights Into Uinta Basin Evolution and Resources

UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SURVEY NOTES VOLUME 51, NUMBER 2 MAY 2019 New core study unearths insights into Uinta Basin evolution and resources CONTENTS New Core, New Insights into Ancient DIRECTOR’S PERSPECTIVE Lake Uinta Evolution and Uinta Basin • Exploration and development of Energy Resources ..........................1 by Bill Keach unconventional resources. Oil shale Drones for Good: Utah Geologists As the incoming Take to the Skies ...........................3 director for the Utah and sand continue to be a provocative Utah Mining Districts at Your Fingertips . .4 Geological Survey opportunity still searching for an eco- Energy News: The Benefits of Utah (UGS), I would like to nomic threshold. Oil and Gas Production.....................6 thank Rick Allis for his Glad You Asked: What are Those • Earthquake early warning systems. Can Blue Ponds Near Moab?....................8 guidance and leader- they work on the Wasatch Front? GeoSights: Pine Park and Ancient ship over the past 18 years. In Rick’s first • Incorporating technology into field Supervolcanoes of Southwestern Utah....10 “Director’s Perspective” he made predic- Survey News...............................12 tions of “likely hot-button issues” that the mapping and hazard recognition and UGS would face. These issues included: using data analytics and knowledge Design | Jenny Erickson sharing in our work at the UGS. Cover | View to the west of Willow Creek • Renewed exploration for oil and gas in core study area. Photo by Ryan Gall. the State. The last item is dear to my heart. A large part of my career has been in the devel- State of Utah • Renewed interest in more fossil-fuel-fired Gary R. -

2019 These Thank-You Cards Came from Students at Reno’S Dorothy Lemelson STEM Academy Elementary School

THE GOOD NEWS Annual Report to Stakeholders 2019 These thank-you cards came from students at Reno’s Dorothy Lemelson STEM Academy Elementary School. Theirs was one of the first groups to come to the College for our Reading & Robes program, launched in 2019. n putting the nishing touches on this report describing events from 2019, we could not help thinking that 2019 seems like a long time ago. Classroom instruction at the NJC, like virtually all colleges and schools, remains on hold because of the COVID-19 public health emergency. Massive protests continue over police brutality and racial injustice. Political Idivisions within the United States, which many already consider to be the worst since the Civil War, only seem to deepen. In these troubled times, we are heartened by your continuing support of our institution and its mission: to make the world a more just place by educating and inspiring the judiciary. We hope you take encouragement and inspiration from what you read in these pages. Our expanding Reading & Robes program is teaching disadvantaged children how justice is supposed to work and about their civic responsibilities. An NJC alumnus helped make the world a safer place for children in Pennsylvania by helping expose cruel crimes. An alumna in Louisiana is helping young victims of human tracking see a brighter future. In Colorado, NJC judges are leading a coaching program that promises a healthier, more sustainable and expert judiciary. “e arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” An abolitionist minister spoke these words in 1871. -

The Tectonic Evolution of the Madrean Archipelago and Its Impact on the Geoecology of the Sky Islands

The Tectonic Evolution of the Madrean Archipelago and Its Impact on the Geoecology of the Sky Islands David Coblentz Earth and Environmental Sciences Division, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM Abstract—While the unique geographic location of the Sky Islands is well recognized as a primary factor for the elevated biodiversity of the region, its unique tectonic history is often overlooked. The mixing of tectonic environments is an important supplement to the mixing of flora and faunal regimes in contributing to the biodiversity of the Madrean Archipelago. The Sky Islands region is located near the actively deforming plate margin of the Western United States that has seen active and diverse tectonics spanning more than 300 million years, many aspects of which are preserved in the present-day geology. This tectonic history has played a fundamental role in the development and nature of the topography, bedrock geology, and soil distribution through the region that in turn are important factors for understanding the biodiversity. Consideration of the geologic and tectonic history of the Sky Islands also provides important insights into the “deep time” factors contributing to present-day biodiversity that fall outside the normal realm of human perception. in the North American Cordillera between the Sierra Madre Introduction Occidental and the Colorado Plateau – Southern Rocky The “Sky Island” region of the Madrean Archipelago (lo- Mountains (figure 1). This part of the Cordillera has been cre- cated between the northern Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico ated by the interactions between the Pacific, North American, and the Colorado Plateau/Rocky Mountains in the Southwest- Farallon (now entirely subducted under North America) and ern United States) is an area of exceptional biodiversity and has Juan de Fuca plates and is rich in geology features, including become an important study area for geoecology, biology, and major plateaus (The Colorado Plateau), large elevated areas conservation management. -

Controls on Geothermal Activity in the Sevier Thermal Belt, Southwestern

PROCEEDINGS, 44th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering Stanford University, Stanford, California, February 11-13, 2019 SGP-TR-214 Controls of Geothermal Resources and Hydrothermal Activity in the Sevier Thermal Belt Based on Fluid Geochemistry Stuart F. Simmons1,2, Stefan Kirby3, Rick Allis3, Phil Wannamaker1 and Joe Moore1 1EGI, University of Utah, 423 Wakara Way, suite 300, Salt Lake City, UT 2Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Utah, 50 S. Central Campus Dr., Salt Lake City, UT 84112 3Utah Geological Survey, 1594 W. North Temple St., Salt Lake City, UT 84114 [email protected] Keywords: Sevier Thermal Belt, hydrothermal systems, heat flow, geochemistry, helium isotopes, stable isotopes. ABSTRACT The Sevier Thermal Belt, southwestern Utah, covers 20,000 km2, and it is located along the eastern edge of the Basin and Range, extending east into the transition zone of the Colorado Plateau. The belt encompasses the geothermal production fields at Cove Fort, Roosevelt Hot Springs, and Thermo, scattered hot spring activity, and the Covenant & Providence hydrocarbon fields. Regionally, it is characterized by elevated heat flow, modest seismicity, and Quaternary basalt-rhyolite magmatism. There are at least five large discrete domains (50 to >500 km2) with anomalous heat flow, including ones associated with Roosevelt Hot Springs, Cove Fort, Thermo and the Black Rock desert. Helium isotope data indicate connections to the upper mantle are developed over the region of strongest and most concentrated hydrothermal activity. By contrast, stable isotope data demonstrate that most of the convective heat transfer is associated with shallow to deep circulation of local meteoric water. Quartz-silica geothermometry suggests that convective heat transfer is compartmentalized by stratigraphic horizons and sub-vertical faults. -

Chapter 3 of the State Wildlife Action Plan

Colorado’s 2015 State Wildlife Action Plan Chapter 3: Habitats This chapter presents updated information on the distribution and condition of key habitats in Colorado. The habitat component of Colorado’s 2006 SWAP considered 41 land cover types from the Colorado GAP Analysis (Schrupp et al. 2000). Since then, the Southwest Regional GAP project (SWReGAP, USGS 2004) has produced updated land cover mapping using the U.S. National Vegetation Classification (NVC) names for terrestrial ecological systems. In the strictest sense, ecological systems are not equivalent to habitat types for wildlife. Ecological systems as defined in the NVC include both dynamic ecological processes and biogeophysical characteristics, in addition to the component species. However, the ecological systems as currently classified and mapped are closely aligned with the ways in which Colorado’s wildlife managers and conservation professionals think of, and manage for, habitats. Thus, for the purposes of the SWAP, references to the NVC systems should be interpreted as wildlife habitat in the general sense. Fifty-seven terrestrial ecological systems or altered land cover types mapped for SWReGAP have been categorized into 20 habitat types, and an additional nine aquatic habitats and seven “Other” habitat categories have been defined. SWAP habitat categories are listed in Table 4 (see Appendix C for the crosswalk of SWAP habitats with SWReGAP mapping units). Though nomenclature is slightly different in some cases, the revised habitat categories presented in this document -

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20549 FORM 10-Q

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q (Mark One) [X] QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE QUARTERLY PERIOD ENDED March 31, 2001. -------------- OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM _______ TO _______. Commission File Number 1-12793 ------- STARTEK, INC. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER) DELAWARE 84-1370538 ------------------------------- ------------------- (STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF (I.R.S. EMPLOYER INCORPORATION OR ORGANIZATION) IDENTIFICATION NO.) 100 GARFIELD STREET DENVER, COLORADO 80206 (ADDRESS OF PRINCIPAL EXECUTIVE OFFICES) (ZIP CODE) (303) 361-6000 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (REGISTRANT'S TELEPHONE NUMBER, INCLUDING AREA CODE) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (FORMER NAME, FORMER ADDRESS AND FORMER FISCAL YEAR, IF CHANGED SINCE LAST REPORT) Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes X No --- --- Indicate the number of shares -

Geology of the Northern Portion of the Fish Lake Plateau, Utah

GEOLOGY OF THE NORTHERN PORTION OF THE FISH LAKE PLATEAU, UTAH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State - University By DONALD PAUL MCGOOKEY, B.S., M.A* The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by Edmund M." Spieker Adviser Department of Geology CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION. ................................ 1 Locations and accessibility ........ 2 Physical features ......... _ ................... 5 Previous w o r k ......... 10 Field work and the geologic map ........ 12 Acknowledgements.................... 13 STRATIGRAPHY........................................ 15 General features................................ 15 Jurassic system......................... 16 Arapien shale .............................. 16 Twist Gulch formation...................... 13 Morrison (?) formation...................... 19 Cretaceous system .............................. 20 General character and distribution.......... 20 Indianola group ............................ 21 Mancos shale. ................... 24 Star Point sandstone................ 25 Blackhawk formation ........................ 26 Definition, lithology, and extent .... 26 Stratigraphic relations . ............ 23 Age . .............................. 23 Price River formation...................... 31 Definition, lithology, and extent .... 31 Stratigraphic relations ................ 34 A g e .................................... 37 Cretaceous and Tertiary systems . ............ 37 North Horn formation. .......... -

If You Have Issues Viewing Or Accessing This File Contact Us at NCJRS.Gov

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. National Criminal Justice Reference Service i ";0; nCJrs This microfiche was produced from documents received for inclusion in the NCJRS data base. Since NCJRS cannot exercise control over the physical condition of the documents submitted, the individual frame quality will vary. The resolution chart on this frame may be used to evaluate the document quality. r;, ;,' "'. { f: t !~ 1 '1, ~ f'~ :1 1- i C :; 11111'2·8 /////2.5 \ i:- 1.0 W [[[[[~~ w 2.2 W ,~~ I Il.I J:i J:. I~ .0 ... u I 1.1 &:.11.:1,1..;. --- ,!~ 125 11111 . 111111.4 . [11111.6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS-1963-A u.~. Department of Just/ce Nahoililllnstitute of Justice This document has been re rodu or organization ,as received lrom the pers~n Origin~tin g .~e~ ~xact/y m this document are those o1 t I, omts 01 view or opinions stated Microfilming procedures used to create this fiche comply with represent the official position 0 he I?~thors and do not necessarily the standards set forth in 41CFR 101-11.504. Justice, r po IC es of the National Institute of Permission to reproduce this' , granted by ~d matenal has been Points of view or opinions stated in this document are Ch j Af ,lusti ce _ Pan 1 \T H C 1 r ---~ -- uOdges those of the author(s) and do not represent the official o orado ,Ind j cia J Dept. 7 _ position or policies of the U. -

Pine River Project D2

Pine River Project Wm. Joe Simonds Bureau of Reclamation 1994 Table of Contents The Pine River Project..........................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................3 Pre-Historic Era...................................................3 Historic Era ......................................................3 Project Authorization.....................................................7 Construction History .....................................................8 Investigations.....................................................8 Construction......................................................8 Post Construction History ................................................14 Settlement of Project Lands ...............................................18 Uses of Project Water ...................................................19 Conclusion............................................................20 About the Author .............................................................20 Bibliography ................................................................21 Archival Collections ....................................................21 Government Documents .................................................21 Magazine Articles ......................................................21 Correspondence ........................................................21 Other Sources..........................................................22 -

Desert Semidesert* Upland* Mountain

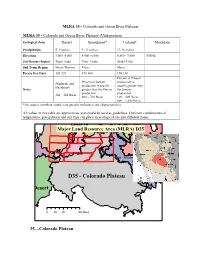

MLRA 35 - Colorado and Green River Plateaus MLRA 35 - Colorado and Green River Plateaus (Utah portion) Ecological Zone Desert Semidesert* Upland* Mountain Precipitation 5 -9 inches 9 -13 inches 13-16 inches Elevation 3,000 -5,000 4,500 -6,500 5,800 - 7,000 NONE Soil Moisture Regime Typic Ardic Ustic Aridic Aridic Ustic Soil Temp Regime Mesic/Thermic Mesic Mesic Freeze free Days 120-220 120-160 100-130 Percent of Pinyon Percent of Juniper production is Shadscale and production is usually usually greater than blackbrush Notes greater than the Pinyon the Juniper production production 300 – 500 lbs/ac 400 – 700 lbs/ac 100 – 500 lbs/ac 800 – 1,000 lbs/ac *the aspect (north or south) can greatly influence site characteristics. All values in this table are approximate and should be used as guidelines. Different combinations of temperature, precipitation and soil type can place an ecological site into different zones. Rocky Mountains Major Land ResourceBasins and Plateaus Area (MLRA) D35 D36 - Southwestern Plateaus, Mesas, and Foothills D35 - Colorado Plateau Desert 07014035 Miles 35—Colorado Plateau This area is in Arizona (56 percent), Utah (22 percent), New Mexico (21 percent), and Colorado (1 percent). It makes up about 71,735 square miles (185,885 square kilometers). The cities of Kingman and Winslow, Arizona, Gallup and Grants, New Mexico, and Kanab and Moab, Utah, are in this area. Interstate 40 connects some of these cities, and Interstate 17 terminates in Flagstaff, Arizona, just outside this MLRA. The Grand Canyon and Petrified Forest National Parks and the Canyon de Chelly and Wupatki National Monuments are in the part of this MLRA in Arizona. -

Colorado Plateau

MLRA 36 – Southwestern Plateaus, Mesas and Foothills MLRA 36 – Southwestern Plateaus, Mesas and Foothills (Utah portion) Ecological Zone Desert Semidesert* Upland* Mountain* Precipitation 5 -9 inches 9 -13 inches 13-16 inches 16-22 inches Elevation 3,000 -5,000 4,500 -6,500 5,800 - 7,000 6,500 – 8,000 Soil Moisture Regime Ustic Aridic Ustic Ustic Ustic Soil Temp Regime Mesic Mesic Mesic Frigid Freeze free Days 120-220 120-160 100-130 60-90 Percent of Pinyon Percent of Juniper production is Shadscale and production is usually usually greater than blackbrush Notes greater than the Pinyon the Juniper Ponderosa Pine production production 300 – 500 lbs/ac 400 – 700 lbs/ac 100 – 500 lbs/ac 800 – 1,000 lbs/ac *the aspect (north or south) can greatly influence site characteristics. All values in this table are approximate and should be used as guidelines. Different combinations of temperature, precipitation and soil type can place an ecological site into different zones. Southern Major Land Resource AreasRocky (MLRA) D36 Mountains Basins and Plateaus s D36 - Southwestern Plateaus, Mesas, and Foothills Colorado Plateau 05010025 Miles 36—Southwestern Plateaus, Mesas, and Foothills This area is in New Mexico (58 percent), Colorado (32 percent), and Utah (10 percent). It makes up about 23,885 square miles (61,895 square kilometers). The major towns in the area are Cortez and Durango, Colorado; Santa Fe and Los Alamos, New Mexico; and Monticello, Utah. Grand Junction, Colorado, and Interstate 70 are just outside the northern tip of this area. Interstates 40 and 25 cross the middle of the area. -

Pioneers, Prospectors and Trout a Historic Context for La Plata County, Colorado

Pioneers, Prospectors and Trout A Historic Context For La Plata County, Colorado By Jill Seyfarth And Ruth Lambert, Ph.D. January, 2010 Pioneers, Prospectors and Trout A Historic Context For La Plata County, Colorado Prepared for the La Plata County Planning Department State Historical Fund Project Number 2008-01-012 Deliverable No. 7 Prepared by: Jill Seyfarth Cultural Resource Planning PO Box 295 Durango, Colorado 81302 (970) 247-5893 And Ruth Lambert, PhD. San Juan Mountains Association PO Box 2261 Durango, Colorado 81302 January, 2010 This context document is sponsored by La Plata County and is partially funded by a grant from the Colorado State Historical Fund (Project Number 2008-01-012). The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the staff of the Colorado State Historical Fund. Cover photographs: Top-Pine River Stage Station. Photo Source: La Plata County Historical Society-Animas Museum Photo Archives. Left side-Gold King Mill in La Plata Canyon taken in about1936. Photo Source Plate 21, in U.S.Geological Survey Professional paper 219. 1949 Right side-Local Fred Klatt’s big catch. Photo Source La Plata County Historical Society- Animas Museum Photo Archives. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 New Frontiers................................................................................................................ 3 Initial Exploration ............................................................................................