England's Glorious Revolution Donald E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auction Results Srandr10145 Wednesday, 28 July 2021

Auction Results srandr10145 Wednesday, 28 July 2021 Lot No Description 1 An oak canteen table, the fitted drawer with lift-out tray, on twist supports, 80cm wide, containing a mixed part set of epns old £50.00 English pattern flatware, etc. 2 An oak canteen of epns old English pattern flatware for six, c/w ivory-handled cutlery and carving set, etc. £100.00 3 A set of Mappin & Webb epns Russell pattern flatware and cutlery for eight settings, 86pcs, in original retailers' box (light use), £220.00 Ato/w large a small rectangular quantity ep of two-handled other electroplated tray, 63 flatware x 39cm, to/w a waisted tray with pierced gallery, 59 x 30cm, a bullet-shaped kettle 5 on stand, two hot water jugs, a tea pot with matching milk jug, and a cased carving set with carved ivory 'scimitar' handles £60.00 (box) 6 A cased set of twelve mother of pearl caviar spoons, to/w a pair of epns entrée dishes and covers with gadrooned rims, three £55.00 electroplated serving bowls and an oak canteen of electroplated fish knives and forks 8 A Walker & Hall two-handled soup tureen and cover on stemmed foot, to/w four entrée dishes and covers (box) £50.00 9 An epns two-handled oval tray with pierced gallery, to/w a compressed melon tea pot, half-reeded coffee pot, plated on £100.00 copper jug (possible Danish design), various flatware, etc. 10 A good set of Christofle (France) electroplated flatware and cutlery of modified fiddle pattern, for twelve settings (87 pcs - little £670.00 used) 11 A quantity of fiddle, thread and shell flatware and cutlery, to/w various other mixed flatware, half-reeded bachelor teapot and £60.00 milk jug, a collection of Churchill and other commemorative crowns (including one silver 1977 Jubilee example), etc. -

Preface Introduction: the Seven Bishops and the Glorious Revolution

Notes Preface 1. M. Barone, Our First Revolution, the Remarkable British Upheaval That Inspired America’s Founding Fathers, New York, 2007; G. S. de Krey, Restoration and Revolution in Britain: A Political History of the Era of Charles II and the Glorious Revolution, London, 2007; P. Dillon, The Last Revolution: 1688 and the Creation of the Modern World, London, 2006; T. Harris, Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685–1720, London, 2006; S. Pincus, England’s Glorious Revolution, Boston MA, 2006; E. Vallance, The Glorious Revolution: 1688 – Britain’s Fight for Liberty, London, 2007. 2. G. M. Trevelyan, The English Revolution, 1688–1689, Oxford, 1950, p. 90. 3. W. A. Speck, Reluctant Revolutionaries, Englishmen and the Revolution of 1688, Oxford, 1988, p. 72. Speck himself wrote the petition ‘set off a sequence of events which were to precipitate the Revolution’. – Speck, p. 199. 4. Trevelyan, The English Revolution, 1688–1689, p. 87. 5. J. R. Jones, Monarchy and Revolution, London, 1972, p. 233. Introduction: The Seven Bishops and the Glorious Revolution 1. A. Rumble, D. Dimmer et al. (compilers), edited by C. S. Knighton, Calendar of State Papers Domestic Series, of the Reign of Anne Preserved in the Public Record Office, vol. iv, 1705–6, Woodbridge: Boydell Press/The National Archives, 2006, p. 1455. 2. Great and Good News to the Church of England, London, 1705. The lectionary reading on the day of their imprisonment was from Two Corinthians and on their release was Acts chapter 12 vv 1–12. 3. The History of King James’s Ecclesiastical Commission: Containing all the Proceedings against The Lord Bishop of London; Dr Sharp, Now Archbishop of York; Magdalen-College in Oxford; The University of Cambridge; The Charter- House at London and The Seven Bishops, London, 1711, pp. -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 1 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Abstract This study explores, reconstructs and evaluates the social, political, educational and economic worlds of the Irish Catholic episcopal corps appointed between 1657 and 1829 by creating a prosopographical profile of this episcopal cohort. The central aim of this study is to reconstruct the profile of this episcopate to serve as a context to evaluate the ‘achievements’ of the four episcopal generations that emerged: 1657-1684; 1685- 1766; 1767-1800 and 1801-1829. The first generation of Irish bishops were largely influenced by the complex political and religious situation of Ireland following the Cromwellian wars and Interregnum. This episcopal cohort sought greater engagement with the restored Stuart Court while at the same time solidified their links with continental agencies. With the accession of James II (1685), a new generation of bishops emerged characterised by their loyalty to the Stuart Court and, following his exile and the enactment of new penal legislation, their ability to endure political and economic marginalisation. Through the creation of a prosopographical database, this study has nuanced and reconstructed the historical profile of the Jacobite episcopal corps and has shown that the Irish episcopate under the penal regime was not only relatively well-organised but was well-engaged in reforming the Irish church, albeit with limited resources. By the mid-eighteenth century, the post-Jacobite generation (1767-1800) emerged and were characterised by their re-organisation of the Irish Church, most notably the establishment of a domestic seminary system and the setting up and manning of a national parochial system. -

Field Dissertation 4

OUTLANDISH AUTHORS: INNOCENZO FEDE AND MUSICAL PATRONAGE AT THE STUART COURT IN LONDON AND IN EXILE by Nicholas Ezra Field A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Stefano Mengozzi, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Clague, Co-Chair Professor Linda K. Gregerson Associate Professor George Hoffmann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In writing this dissertation I have benefited from the assistance, encouragement, and guidance of many people. I am deeply grateful to my thesis advisors and committee co-chairs, Professor Stefano Mengozzi and Professor Mark Clague for their unwavering support as this project unfolded. I would also like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my dissertation committee members, Professor Linda Gregerson and Professor George Hoffmann—thank you both for your interest, insights, and support. Additional and special thanks are due to my family: my parents Larry and Tamara, my wife Yunju and her parents, my brother Sean, and especially my beloved children Lydian and Evan. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................................ ii LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ v ABSTRACT....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER ONE: Introduction -

Restoration, Religion, and Revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Restoration, religion, and revenge Heather Thornton Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Thornton, Heather, "Restoration, religion, and revenge" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 558. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/558 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESTORATION, RELIGION AND REVENGE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Heather D. Thornton B.A., Lousiana State University, 1999 M. Div., Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary, 2002 December 2005 In Memory of Laura Fay Thornton, 1937-2003, Who always believed in me ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank many people who both encouraged and supported me in this process. My advisor, Dr. Victor Stater, offered sound criticism and advice throughout the writing process. Dr. Christine Kooi and Dr. Maribel Dietz who served on my committee and offered critical outside readings. I owe thanks to my parents Kevin and Jorenda Thornton who listened without knowing what I was talking about as well as my grandparents Denzil and Jo Cantley for prayers and encouragement. -

The Glorious Revolution

HOUSE OF COMMONS PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE FACTSHEET No 8 THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION 1988 marked the tercentenary of the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. This was the series of events which culminated in the exile of King James II (reigned 1685-88) and the accession to the throne of William and Mary. It has also been seen as a watershed in the development of the constitution and especially of the role of Parliament. This Factsheet is an attempt to explain why. (An illustration is available in hard copy only) Presentation of the Declaration of Rights to William and Mary in the Banqueting House. EVENTS OF 1685-1689 1685 6 February: Death of Charles II and succession of the Catholic, James II. In spite of widespread fears of Catholicism, and the previous attempts which had been made to exclude James II from the throne, the succession occurred without incident, and in fact on 19 May, when James's Parliament met, it was overwhelmingly loyalist in composition. The House voted James for life the same revenues his brother had enjoyed, and indeed after the invasions of Argyle and Monmouth (the Duke of Monmouth was the illegitimate son of Charles II), the Commons voted additional grants, accompanied by fervent protestations of loyalty. However, this fervour did not last. When the House was recalled after the summer, James asked the Commons for more money for the maintenance of his standing army. He further antagonised them by asking for the repeal of the Test Acts. These were the Acts which required office holders to prove that they were not Catholics by making a declaration against transubstantiation. -

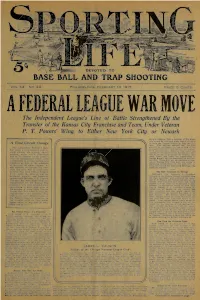

Spring' Base Ball

DEVOTED TO BASE BALL AND TRAP SHOOTING VOL. 64. NO. 24 PHILADELPHIA, FEBRUARY 13, 1915 PRICE 5 CENTS A FEDERAL LEAGUE WAR MOVE The Independent League's Line of Battle Strengthened By the Transfer of the Kansas City Franchise and Team, Under Veteran P. T. Powers' Wing, to Either New York City or Newark more's telegram that a meeting of the direc tors wonld be held and plans would be mads A Vital Circuit Change to force the Federal League to keep the club here. Club officials contend that the time granted by the league for the raising of the The independent Federal League necessary $100,080 fund has not yet expired. has taken a long-erpccted step to It is conceded here, however, that under the ward solving the serious circuit conditions the affairs of the Kansas City Club problem, under "^ich 1'ittaburgh will be wound up as quickly as possible. The had to be claaeit as an Eastern team, intact, and under the management of city an arrangement which made George Stovmll, will be transferred to the East ern city. Those who are stockholders at pres it impossible to arrange satisfactory ent in Kansas City Club have the option of schedules as foils to the schedules remaining stockholders in the new club or of the rii-al old major leagues. As being reimbursed for their stock koldings who was expected, the Kansas City fran make the request. chise and team will be transferred to either Xew York City or Newark, The Sale Confirmed In Chicago X. -

English Bill of Rights

WorldHistoryAtlas.com PRIMARY SOURCES English Bill of Rights Date I December 16, 1689 Place I London, England Type of Source I Government Document (original in English) Author I English Parliament Historical Context I In 1685 James II, a Roman Catholic, was crowned king of England and Scotland. James’ at-times vicious suppression of opponents led to fears of an absolute monarchy and the restoration of the Catholic Church. In what became known as the Glorious Revolution, Parliament conspired with Dutch leader William of Orange, James’ son-in-law, to overthrow the king. In 1688 William landed an army in Britain. James escaped to France. Parliament insisted that William and his wife Mary agree to a bill of rights before acknowledging them as joint monarchs. Many viewed this as an example of John Locke’s theory of social contract. The Bill of Rights is a major part of the British constitution and became the basis for most later human rights documents around the world. Lords Spiritual and Temporal the House of Lords, the Whereas the Lords Spiritual and Temporal and Commons bishops and nobility assembled at Westminster , lawfully, fully and freely representing all the Commons estates of the people of this realm, did upon the thirteenth day of February the House of Commons, in the year of our Lord one thousand six hundred eighty-[nine] [ old style elected members of date ] present unto their Majesties, then called and known by the names and Parliament style of William and Mary, prince and princess of Orange , being present in Westminster their proper persons, a certain declaration in writing made by the said Lords Westminster Palace in London is the where and Commons in the words following, viz.: Parliament meets. -

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra Sunday / July 18 / 4:00Pm / Venetian Theater

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

"James II, and the Seven Bishops," the Churchman

THE CHURCHMAN AUGUST, 1880. ART. I.-JAMES.. II. AND THE SEVEN BISHOPS . COME now to the closing scene in King James' disgraceful reign, the prosecution and trial of the Seven Bishops. The Iimportance of that event is so great, and the consequences which resulted from it were so immense, that I must enter some what fully into its details. I do so the more willingly because attempts are sometimes made now-a-days to misrepresent this trial, to place the motives of the bishops in a wrong light, and to obscure the real issues which were at stake. Some men will do, anything in these times to mystify the public mind, to pervert history, and to whitewash the Church of Rome. But I have made it my business to search up every authority I can find about this era. I have no doubt whatever where the truth lies. And I shall try to set before my readers the " thing as it is." The origin of the trial of the Seven Bishops was a proclama tion put forth by James II., on the 27th of April, 1688, called the " Declaration of Indulgence." It was a Declaration which differed little from one put forth on the April of 1687. But it was followed by an " Order of Council" that it was to be read on two successive Sundays, in divine service, by all the officiating ministers in all the churches and chapels of the kingdom. In London the reading was to take place on the 20th and 27th of llfay, and in other parts of England on the 3rd and 10th of June. -

Albuquerque Daily Citizen, 06-07-1901 Hughes & Mccreight

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-7-1901 Albuquerque Daily Citizen, 06-07-1901 Hughes & McCreight Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news Recommended Citation Hughes & McCreight. "Albuquerque Daily Citizen, 06-07-1901." (1901). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news/1308 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r; Book Binding J 4 Blank Book Wrk job Printing promptly eseciiteel In tome) la all Ita wmmm a4 tyle at TUB CITIZEN vara kraacMa) aa It Bindery. ! should ba at TUB CrTUHN The AlBUttUEKQUIS Daily (Citizen. Job Rooms. VOLUME 15. ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, FRIDAY AFTERNOON, JUNE 7. 1901. NUMBER 171 to last himself and companion sev tlcal turn. There was not as much eral days. It Is learned that In tha theorizing as is usually seen In the a: payment average EIICLMEIIDIY! of these purchases ha dis college oration. The college PARIS DUEL Agent played quite a roll of money, and seess to produce men and women lit for kept his eyes on every person who ted for the natural conditions around McCALL BAZAAR MAIL ORDERS chanced to be nearby. Tha com them. The delivery of the graduates PATTERNS. on Filled Same panlon. who remained hi horse showed that they had considerable All Pattern io A ijc THE and held the other, seemed to ba ner drill and practice in speaking. -

Presbyterianism, Royalism and Ministry in 1650S Lancashire: John Lake As Minister at Oldham, C

This is a repository copy of Presbyterianism, royalism and ministry in 1650s Lancashire: John Lake as minister at Oldham, c. 1650-1654. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85246/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Mawdesley, J. (2015) Presbyterianism, royalism and ministry in 1650s Lancashire: John Lake as minister at Oldham, c. 1650-1654. The Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society, 108. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ John Lake revised article: June 2013 James Mawdesley Presbyterianism, royalism and ministry in 1650s Lancashire: John Lake as minister at Oldham, c. 1650-1654* James Mawdesley The University of Sheffield Late in life, John Lake attained his place in the annals of English history.