Stellar Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Solar System and Its Place in the Galaxy in Encyclopedia of the Solar System by Paul R

Giant Molecular Clouds http://www.astro.ncu.edu.tw/irlab/projects/project.htm Æ Galactic Open Clusters Æ Galactic Structure Æ GMCs The Solar System and its Place in the Galaxy In Encyclopedia of the Solar System By Paul R. Weissman http://www.academicpress.com/refer/solar/Contents/chap1.htm Stars in the galactic disk have different characteristic velocities as a function of their stellar classification, and hence age. Low-mass, older stars, like the Sun, have relatively high random velocities and as a result c an move farther out of the galactic plane. Younger, more massive stars have lower mean velocities and thus smaller scale heights above and below the plane. Giant molecular clouds, the birthplace of stars, also have low mean velocities and thus are confined to regions relatively close to the galactic plane. The disk rotates clockwise as viewed from "galactic north," at a relatively constant velocity of 160-220 km/sec. This motion is distinctly non-Keplerian, the result of the very nonspherical mass distribution. The rotation velocity for a circular galactic orbit in the galactic plane defines the Local Standard of Rest (LSR). The LSR is then used as the reference frame for describing local stellar dynamics. The Sun and the solar system are located approxi-mately 8.5 kpc from the galactic center, and 10-20 pc above the central plane of the galactic disk. The circular orbit velocity at the Sun's distance from the galactic center is 220 km/sec, and the Sun and the solar system are moving at approximately 17 to 22 km/sec relative to the LSR. -

Revisiting the Pre-Main-Sequence Evolution of Stars I. Importance of Accretion Efficiency and Deuterium Abundance ?

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. Kunitomo_etal c ESO 2018 March 22, 2018 Revisiting the pre-main-sequence evolution of stars I. Importance of accretion efficiency and deuterium abundance ? Masanobu Kunitomo1, Tristan Guillot2, Taku Takeuchi,3,?? and Shigeru Ida4 1 Department of Physics, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 464-8602, Japan e-mail: [email protected] 2 Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, CNRS UMR 7293, 06304 Nice CEDEX 04, France 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8551, Japan 4 Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8551, Japan Received 5 February 2016 / Accepted 6 December 2016 ABSTRACT Context. Protostars grow from the first formation of a small seed and subsequent accretion of material. Recent theoretical work has shown that the pre-main-sequence (PMS) evolution of stars is much more complex than previously envisioned. Instead of the traditional steady, one-dimensional solution, accretion may be episodic and not necessarily symmetrical, thereby affecting the energy deposited inside the star and its interior structure. Aims. Given this new framework, we want to understand what controls the evolution of accreting stars. Methods. We use the MESA stellar evolution code with various sets of conditions. In particular, we account for the (unknown) efficiency of accretion in burying gravitational energy into the protostar through a parameter, ξ, and we vary the amount of deuterium present. Results. We confirm the findings of previous works that, in terms of evolutionary tracks on the Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) diagram, the evolution changes significantly with the amount of energy that is lost during accretion. -

Stellar Dynamics and Stellar Phenomena Near a Massive Black Hole

Stellar Dynamics and Stellar Phenomena Near A Massive Black Hole Tal Alexander Department of Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Weizmann Institute of Science, 234 Herzl St, Rehovot, Israel 76100; email: [email protected] | Author's original version. To appear in Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. See final published version in ARA&A website: www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-astro-091916-055306 Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2017. Keywords 55:1{41 massive black holes, stellar kinematics, stellar dynamics, Galactic This article's doi: Center 10.1146/((please add article doi)) Copyright c 2017 by Annual Reviews. Abstract All rights reserved Most galactic nuclei harbor a massive black hole (MBH), whose birth and evolution are closely linked to those of its host galaxy. The unique conditions near the MBH: high velocity and density in the steep po- tential of a massive singular relativistic object, lead to unusual modes of stellar birth, evolution, dynamics and death. A complex network of dynamical mechanisms, operating on multiple timescales, deflect stars arXiv:1701.04762v1 [astro-ph.GA] 17 Jan 2017 to orbits that intercept the MBH. Such close encounters lead to ener- getic interactions with observable signatures and consequences for the evolution of the MBH and its stellar environment. Galactic nuclei are astrophysical laboratories that test and challenge our understanding of MBH formation, strong gravity, stellar dynamics, and stellar physics. I review from a theoretical perspective the wide range of stellar phe- nomena that occur near MBHs, focusing on the role of stellar dynamics near an isolated MBH in a relaxed stellar cusp. -

Astr-Astronomy 1

ASTR-ASTRONOMY 1 ASTR 1116. Introduction to Astronomy Lab, Special ASTR-ASTRONOMY 1 Credit (1) This lab-only listing exists only for students who may have transferred to ASTR 1115G. Introduction Astro (lec+lab) NMSU having taken a lecture-only introductory astronomy class, to allow 4 Credits (3+2P) them to complete the lab requirement to fulfill the general education This course surveys observations, theories, and methods of modern requirement. Consent of Instructor required. , at some other institution). astronomy. The course is predominantly for non-science majors, aiming Restricted to Las Cruces campus only. to provide a conceptual understanding of the universe and the basic Prerequisite(s): Must have passed Introduction to Astronomy lecture- physics that governs it. Due to the broad coverage of this course, the only. specific topics and concepts treated may vary. Commonly presented Learning Outcomes subjects include the general movements of the sky and history of 1. Course is used to complete lab portion only of ASTR 1115G or ASTR astronomy, followed by an introduction to basic physics concepts like 112 Newton’s and Kepler’s laws of motion. The course may also provide 2. Learning outcomes are the same as those for the lab portion of the modern details and facts about celestial bodies in our solar system, as respective course. well as differentiation between them – Terrestrial and Jovian planets, exoplanets, the practical meaning of “dwarf planets”, asteroids, comets, ASTR 1120G. The Planets and Kuiper Belt and Trans-Neptunian Objects. Beyond this we may study 4 Credits (3+2P) stars and galaxies, star clusters, nebulae, black holes, and clusters of Comparative study of the planets, moons, comets, and asteroids which galaxies. -

Stellar Evolution

Stellar Astrophysics: Stellar Evolution 1 Stellar Evolution Update date: December 14, 2010 With the understanding of the basic physical processes in stars, we now proceed to study their evolution. In particular, we will focus on discussing how such processes are related to key characteristics seen in the HRD. 1 Star Formation From the virial theorem, 2E = −Ω, we have Z M 3kT M GMr = dMr (1) µmA 0 r for the hydrostatic equilibrium of a gas sphere with a total mass M. Assuming that the density is constant, the right side of the equation is 3=5(GM 2=R). If the left side is smaller than the right side, the cloud would collapse. For the given chemical composition, ρ and T , this criterion gives the minimum mass (called Jeans mass) of the cloud to undergo a gravitational collapse: 3 1=2 5kT 3=2 M > MJ ≡ : (2) 4πρ GµmA 5 For typical temperatures and densities of large molecular clouds, MJ ∼ 10 M with −1=2 a collapse time scale of tff ≈ (Gρ) . Such mass clouds may be formed in spiral density waves and other density perturbations (e.g., caused by the expansion of a supernova remnant or superbubble). What exactly happens during the collapse depends very much on the temperature evolution of the cloud. Initially, the cooling processes (due to molecular and dust radiation) are very efficient. If the cooling time scale tcool is much shorter than tff , −1=2 the collapse is approximately isothermal. As MJ / ρ decreases, inhomogeneities with mass larger than the actual MJ will collapse by themselves with their local tff , different from the initial tff of the whole cloud. -

Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram and Mass Distribution of Barium Stars ? A

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. HRD_Ba c ESO 2019 May 14, 2019 Hertzsprung-Russell diagram and mass distribution of barium stars ? A. Escorza1; 2, H.M.J. Boffin3, A.Jorissen2, S. Van Eck2, L. Siess2, H. Van Winckel1, D. Karinkuzhi2, S. Shetye2; 1, and D. Pourbaix2 1 Institute of Astronomy, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium 2 Institut d’Astronomie et d’Astrophysique, Université Libre de Bruxelles, ULB, Campus Plaine C.P. 226, Boulevard du Triomphe, B-1050 Bruxelles, Belgium 3 ESO, Karl Schwarzschild Straße 2, D-85748 Garching bei München, Germany Received; Accepted ABSTRACT With the availability of parallaxes provided by the Tycho-Gaia Astrometric Solution, it is possible to construct the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (HRD) of barium and related stars with unprecedented accuracy. A direct result from the derived HRD is that subgiant CH stars occupy the same region as barium dwarfs, contrary to what their designations imply. By comparing the position of barium stars in the HRD with STAREVOL evolutionary tracks, it is possible to evaluate their masses, provided the metallicity is known. We used an average metallicity [Fe/H] = −0.25 and derived the mass distribution of barium giants. The distribution peaks around 2.5 M with a tail at higher masses up to 4.5 M . This peak is also seen in the mass distribution of a sample of normal K and M giants used for comparison and is associated with stars located in the red clump. When we compare these mass distributions, we see a deficit of low-mass (1 – 2 M ) barium giants. -

Systematic Motions in the Galactic Plane Found in the Hipparcos

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. cabad0609 September 30, 2018 (DOI: will be inserted by hand later) Systematic motions in the galactic plane found in the Hipparcos Catalogue using Herschel’s Method Carlos Abad1,2 & Katherine Vieira1,3 (1) Centro de Investigaciones de Astronom´ıa CIDA, 5101-A M´erida, Venezuela e-mail: [email protected] (2) Grupo de Mec´anica Espacial, Depto. de F´ısica Te´orica, Universidad de Zaragoza. 50006 Zaragoza, Espa˜na (3) Department of Astronomy, Yale University, P.O. Box 208101 New Haven, CT 06520-8101, USA e-mail: [email protected] September 30, 2018 Abstract. Two motions in the galactic plane have been detected and characterized, based on the determination of a common systematic component in Hipparcos catalogue proper motions. The procedure is based only on positions, proper motions and parallaxes, plus a special algorithm which is able to reveal systematic trends. Our results come o o o o from two stellar samples. Sample 1 has 4566 stars and defines a motion of apex (l,b) = (177 8, 3 7) ± (1 5, 1 0) and space velocity V = 27 ± 1 km/s. Sample 2 has 4083 stars and defines a motion of apex (l,b)=(5o4, −0o6) ± o o (1 9, 1 1) and space velocity V = 32 ± 2 km/s. Both groups are distributed all over the sky and cover a large variety of spectral types, which means that they do not belong to a specific stellar population. Herschel’s method is used to define the initial samples of stars and later to compute the common space velocity. -

ASTRON 449: Stellar Dynamics Winter 2017 in This Course, We Will Cover

ASTRON 449: Stellar Dynamics Winter 2017 In this course, we will cover • the basic phenomenology of galaxies (including dark matter halos, stars clusters, nuclear black holes) • theoretical tools for research on galaxies: potential theory, orbit integration, statistical description of stellar systems, stability of stellar systems, disk dynamics, interactions of stellar systems • numerical methods for N-body simulations • time permitting: kinetic theory, basics of galaxy formation Galaxy phenomenology Reading: BT2, chap. 1 intro and section 1.1 What is a galaxy? The Milky Way disk of stars, dust, and gas ~1011 stars 8 kpc 1 pc≈3 lyr Sun 6 4×10 Msun black hole Gravity turns gas into stars (all in a halo of dark matter) Galaxies are the building blocks of the Universe Hubble Space Telescope Ultra-Deep Field Luminosity and mass functions MW is L* galaxy Optical dwarfs Near UV Schechter fits: M = 2.5 log L + const. − 10 Local galaxies from SDSS; Blanton & Moustakas 08 Hubble’s morphological classes bulge or spheroidal component “late type" “early type" barred http://skyserver.sdss.org/dr1/en/proj/advanced/galaxies/tuningfork.asp Not a time or physical sequence Galaxy rotation curves: evidence for dark matter M33 rotation curve from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galaxy_rotation_curve Galaxy clusters lensing arcs Abell 1689 ‣ most massive gravitational bound objects in the Universe ‣ contain up to thousands of galaxies ‣ most baryons intracluster gas, T~107-108 K gas ‣ smaller collections of bound galaxies are called 'groups' Bullet cluster: more -

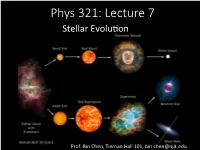

Phys 321: Lecture 7 Stellar Evolu�On

Phys 321: Lecture 7 Stellar Evolu>on Prof. Bin Chen, Tiernan Hall 101, [email protected] Stellar Evoluon • Formaon of protostars (covered in Phys 320; briefly reviewed here) • Pre-main-sequence evolu>on (this lecture) • Evolu>on on the main sequence (this lecture) • Post-main-sequence evolu>on (this lecture) • Stellar death (next lecture) The Interstellar Medium and Star Formation the cloud’s internal kinetic energy, given by The Interstellar Medium and Star Formation the cloud’s internal kinetic energy, given by 3 K NkT, 3 = 2 The Interstellar MediumK andNkT, Star Formation = 2 where N is the total number2 ofTHE particles. FORMATIONwhere ButNNisis the just total OF number PROTOSTARS of particles. But N is just M Mc N c , Our understandingN , of stellar evolution has= µm developedH significantly since the 1960s, reaching = µmH the pointwhere whereµ is the much mean of molecular the life weight. history Now, of by a the star virial is theorem, well determined. the condition for This collapse success has been where µ is the mean molecular weight.due to advances Now,(2K< byU the in) becomes observational virial theorem, techniques, the condition improvements for collapse in our knowledge of the physical | | (2K< U ) becomes processes important in stars, and increases in computational2 power. In the remainder of this | | 3MckT 3 GMc chapter, we will present an overview of< the lives. of stars, leaving de(12)tailed discussions 2 µmH 5 Rc of s3oMmeckTspecia3l pGMhasces of evolution until later, specifically stellar pulsation, supernovae, The radius< may be replaced. by using the initial mass density(12) of the cloud, ρ , assumed here µmH 5 Rc 0 and comtop beac constantt objec throughoutts (stellar theco cloud,rpses). -

Numerical Computations in Stellar Dynamics

Particle Accelerators, 1986, Vol. 19, pp. 37-42 0031-2460/86/1904-0037/$15.00/0 © 1986 Gordon and Breach, Science Publishers, S.A. Printed in the United States of America NUMERICAL COMPUTATIONS IN STELLAR DYNAMICS PIET HUTt Department ofAstronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 An outline is given of the main similarities and differences between gravitational dynamics and the other fields of interest at the present conference: accelerator orbital dynamics and plasma physics. Gravitational dynamics can be divided into two rather distinct fields, celestial mechanics and stellar dynamics. The field of stellar dynamics is concerned with astrophysical applications of the general gravitational N -body problem, which addresses the question: for a system of N point masses with given initial conditions, describe its evolution under Newtonian gravity. Major subfields within stellar dynamics are listed and classified according to the collisional or collisionless character of different problems. A number of review papers are mentioned and briefly discussed, to provide a few starting points for exploring the vast recent literature on stellar dynamics. I. INTRODUCTION Gravitational dynamics naturally divides into two rather distinct fields, celestial mechanics and stellar dynamics. The former is concerned with the long-term evolution of well-behaved, small, and ordered systems such as the motion of the planets around the sun, and that of natural and artificial satellites around the sun and planets. The latter covers the behavior of much larger systems consisting of many particles, each of which move on random paths constrained only by a globally averaged distribution, just as atoms move in a gas. -

Module 14 H. R. Diagram TABLE of CONTENTS 1. Learning Outcomes

Module 14 H. R. Diagram TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Learning Outcomes 2. Introduction 3. H. R. Diagram 3.1. Coordinates of H. R. Diagram 3.2. Stellar Families 3.3. Hertzsprung Gap 3.4. H. R. Diagram and Stellar Radii 4. Summary 1. Learning Outcomes After studying this module, you should be able to recognize an H. R. Diagram explain the coordinates of an H. R. Diagram appreciate the shape of an H. R. Diagram understand that in this diagram stars appear in distinct families recount the characteristics of these families recognize that there is a real gap in the horizontal branch of the diagram, called the Hertzsprung gap explain that during their evolution stars pass very rapidly through this region and therefore there is a real paucity of stars here derive the shape of the 퐥퐨퐠 푻 − 퐥퐨퐠 푳 plot at a given stellar radius explain that the stellar radius (and mass) increases upwards in the H. R. Diagram 2. Introduction In the last few modules we have discussed the stellar spectra and spectral classification based on stellar spectra. The Harvard system of spectral classification categorized stellar spectra in 7 major classes, from simple spectra containing only a few lines to spectra containing a huge number of lines and molecular bands. The major classes were named O, B, A, F, G, K and M. Each major class was further subdivided into 10 subclasses, running from 0 to 9. Considering the bewildering variety of stellar spectra, classes Q, P and Wolf-Rayet had to be introduced at the top of the classification and classes R and N were introduced at the bottom of the classification scheme. -

Structure and Evolution of FK Comae Corona

A&A 383, 919–932 (2002) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20011810 & c ESO 2002 Astrophysics Structure and evolution of FK Comae corona P. Gondoin, C. Erd, and D. Lumb Space Science Department, European Space Agency – Postbus 299, 2200 AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands Received 16 October 2001 / Accepted 17 December 2001 Abstract. FK Comae (HD 117555) is a rapidly rotating single G giant whose distinctive characteristics include a quasisinusoidal optical light curve and high X-ray luminosity. FK Comae was observed twice at two weeks interval in January 2001 by the XMM-Newton space observatory. Analysis results suggest a scenario where the corona of FK Comae is dominated by large magnetic structures similar in size to interconnecting loops between solar active regions but significantly hotter. The interaction of these structures themselves could explain the permanent flaring activity on large scales that is responsible for heating FK Comae plasma to high temperatures. During our observations, these flares were not randomly distributed on the star surface but were partly grouped within a large compact region of about 30 degree extent in longitude reminiscent of a large photospheric spot. We argue that the α − Ω dynamo driven activity on FK Comae will disappear in the future with the effect of suppressing large scale magnetic structures in its corona. Key words. stars: individual: FK Comae – stars: activity – stars: coronae – stars: evolution – stars: late-type – X-ray: stars 1. Introduction ments and their temporal behaviour during the observa- tions. Sections 5 and 6 describe the spectral analysis of the FK Comae (HD 117555) is the prototype of a small group EPIC and RGS datasets.