A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Summer 1996 $15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature

PAYING ATTENTION TO PUBLIC READERS OF CANADIAN LITERATURE: POPULAR GENRE SYSTEMS, PUBLICS, AND CANONS by KATHRYN GRAFTON BA, The University of British Columbia, 1992 MPhil, University of Stirling, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Kathryn Grafton, 2010 ABSTRACT Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature examines contemporary moments when Canadian literature has been canonized in the context of popular reading programs. I investigate the canonical agency of public readers who participate in these programs: readers acting in a non-professional capacity who speak and write publicly about their reading experiences. I argue that contemporary popular canons are discursive spaces whose constitution depends upon public readers. My work resists the common critique that these reading programs and their canons produce a mass of readers who read the same work at the same time in the same way. To demonstrate that public readers are canon-makers, I offer a genre approach to contemporary canons that draws upon literary and new rhetorical genre theory. I contend in Chapter One that canons are discursive spaces comprised of public literary texts and public texts about literature, including those produced by readers. I study the intertextual dynamics of canons through Michael Warner’s theory of publics and Anne Freadman’s concept of “uptake.” Canons arise from genre systems that are constituted to respond to exigencies readily recognized by many readers, motivating some to participate. I argue that public readers’ agency lies in the contingent ways they select and interpret a literary work while taking up and instantiating a canonizing genre. -

Oolichan Spring 2011 Catalogue

Oolichan Books Spring Titles 2011 1 Award Winning Oolichan Books 2010 Finalists Congratulations to Betty Jane Hegerat for being shortlisted for the Georges Bugnet Award for Fiction, the Alberta Book Awards 2010 for Delivery. Congratulations to Miranda Pearson for her nomination of Harbour for the BC Book Awards Dorothy Livesay Award. 2009 Winner Oolichan Books would like to congratulate Bruce Hunter for winning the 2009 Banff Mountain Book Festival’s Canadian Rockies Award for his book In The Bear’s House. Governor General’s Award for Poetry The Literary Network Top Ten Canadian Poetry Books 2006 John Pass, Stumbling In The Bloom, Winner 1999 Mona Fertig, Sex, Death & Travel 2005 W.H. New, Underwood Log, Finalist QSPELL Mavis Gallant Prize for Non-Fiction 2004 David Manicom, The Burning Eaves, Finalist 1998 David Manicom 2001 John Pass, Water Stair, Finalist Progeny of Ghosts: Travels in Russia and the Old Empire., Winner Governor General’s Award for Fiction QSPELL A.M. Klein Award for Poetry 1993 Carol Windley, Visible Light, Short List 1998 David Manicom. The Older Graces, Finalist BC Book Prizes - Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize Viacom Canada Writers’ Trust Non-Fiction Prize 2010 Miranda Pearson, Harbour, Finalist 1998 David Manicom 2009 Nilofar Shidmehr, Shrin and Salt Man, Finalist Progeny of Ghosts: Travels in Russia and the Old Empire., Finalist 2008 George McWhirter, The Incorrection, Finalist 2005 Eve Joseph, The Startled Heart, Finalist Gerald Lampert Memorial Prize 2001 John Pass, Water Stair, Finalist 1997 Margo Button, The Unhinging -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Stuart Ross to Receive the 2019 Harbourfront Festival Prize

Stuart Ross to Receive the 2019 Harbourfront Festival Prize TORONTO, September 17, 2019 – The Toronto International Festival of Authors (TIFA), Canada’s largest and longest-running festival of words and ideas, today announced that this year’s Harbourfront Festival Prize will be awarded to writer and poet Stuart Ross. Established in 1984, the Harbourfront Festival Prize of $10,000 is presented annually in recognition of an author's contribution to the Canadian literature community. The award will be presented to Ross on Sunday, October 27 at 4pm as part of TIFA’s annual GGbooks: A Festival Celebration event, hosted by Carol Off. Ross will also appear at TIFA as part of Small Press, Big Ideas: A Roundtable on Saturday, October 26, 2019 at 5pm. TIFA takes place from October 24 to November 3 and tickets are on sale at FestivalOfAuthors.ca. Stuart Ross is a writer, editor, writing teacher and small press activist living in Cobourg, Ontario. He is the author of 20 books of poetry, fiction and essays, most recently the poetry collection Motel of the Opposable Thumbs and the novel in prose poems Pockets. Ross is a founding member of the Meet The Presses collective, has taught writing workshops across the country, and was the 2010 Writer In Residence at Queen’s University. He is the winner of TIFA’s 2017 PoetryNOW:Battle of the Bards competition, the 2017 Jewish Literary Award for Poetry, and the 2010 ReLit Award for Short Fiction, among others. His micro press, Proper Tales, is in its 40th year. “I am both stunned and honoured to receive this award. -

Download Full Issue

191CanLitWinter2006-4 1/23/07 1:04 PM Page 1 Canadian Literature/ Littératurecanadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number , Winter Published by The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Laurie Ricou Associate Editors: Laura Moss (Reviews), Glenn Deer (Reviews), Kevin McNeilly (Poetry), Réjean Beaudoin (Francophone Writing), Judy Brown (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (1959–1977), W.H. New, Editor emeritus (1977–1995), Eva-Marie Kröller (1995–2003) Editorial Board Heinz Antor Universität Köln Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Coral Ann Howells University of Reading Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Louise Ladouceur University of Alberta Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Judit Molnár University of Debrecen Leslie Monkman Queen’s University Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Élizabeth Nardout-Lafarge Université de Montréal Ian Rae Universität Bonn Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke Patricia Smart Carleton University David Staines University of Ottawa Penny van Toorn University of Sydney David Williams University of Manitoba Mark Williams University of Canterbury Editorial Laura Moss Playing the Monster Blind? The Practical Limitations of Updating the Canadian Canon Articles Caitlin J. Charman There’s Got to Be Some Wrenching and Slashing: Horror and Retrospection in Alice Munro’s “Fits” Sue Sorensen Don’t Hanker to Be No Prophet: Guy Vanderhaeghe and the Bible Andre Furlani Jan Zwicky: Lyric Philosophy Lyric Daniela Janes Brainworkers: The Middle-Class Labour Reformer and the Late-Victorian Canadian Industrial Novel 191CanLitWinter2006-4 1/23/07 1:04 PM Page 2 Articles, continued Gillian Roberts Sameness and Difference: Border Crossings in The Stone Diaries and Larry’s Party Poems James Pollock Jack Davis Susan McCaslin Jim F. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Imaginary) Boyfriend

! "! (Imaginary) Boyfriend by Toby Cygman A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English, Film, and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2011 by Toby Cygman ! ! #! ! Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...ii Preface (read at thesis defense)……………………………………………………….1 Mobile……………………………………………………………………………………..7 Internets………...………………………………………………………………………12 Baggage…………………………………………………...……………………………18 Effexor for the Win……………………………………………………………………..23 Minor Injuries………………………………………………...…………………………37 Past Perfect……………………………………………………...……………………..47 Stories to My (Imaginary) Boyfriend………………………………………………….50 Lady, Motorbike………………………………………………………………………...53 Afterword………………………………………………………………………………..62 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………….79 ! ##! Abstract (Imaginary) Boyfriend is a cycle of short stories that addresses the tension between stasis and locomotion. The eight stories feature characters who are addicted to motion, but paralyzed by anxiety. This theme manifests itself in both the internal and external spaces the characters occupy. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "! Preface As I was working on my thesis, I looked at other U of M creative theses for direction and inspiration. I found that the large majority of creative theses from the last few years are novellas and began to wonder about my chosen genre, the short story. My preference for this medium has to do with immediacy. -

The “New-Formed Leaves” of Juvenilia Press Natasha Duquette Biola University

The “New-Formed Leaves” of Juvenilia Press Natasha Duquette Biola University April has brought the youngest time of year, With clinging cloaks of rain and mist, silver-gray; The velvet, star-wreathed night, and wind-clad day; And song of meadow larks from uplands near. The new-formed leaves unfold to greet the sun, Whose light is warming fields still moist with rain, While down each city street and grass-fringed lane, Children are shouting gladly as they run. Margaret Laurence “Song for Spring, 1944, Canada” he above octave from margaret laurence’s Petrarchan sonnet Tconstructs parallels between the new-born, “youngest” time of year, the “new-formed leaves” of budding trees, and newly freed children bursting out from the confines of a long Canadian winter. Her “Song for Spring, 1944, Canada” is part of the collection Embryo Words: Margaret Laurence’s Early Writings (1997) published by Juvenilia Press. This press, founded by Juliet McMaster of the University of Alberta and now under the direc- torship of Christine Alexander at the University of New South Wales in Australia, publishes literary texts produced by children or teens. ESC 37.3–4 (September/December 2011): 201–218 Lest we dismiss the merit of such youthful writing, we need only recall that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein started as a piece of juvenilia.1 The biased critical objection that Frankenstein is too good to have been written by a Natasha Duquette female teenager (and must have actually been written by Percy Shelley) received her ma from is often leveled at young writers. Peter Paul Rubens and the Friendly Folk the University of Toronto is a Juvenilia Press title containing text written by Opal Whitely at age six and her PhD from to seven, and its editor Lesley Peterson notes, “The diary was too good, Queen’s University. -

At a Glance 10:00 Am – 10:45 Am 9:00 Am – 10:00 Am 37

Wednesday, September 22 Saturday, September 25 7:30 pm – 10:30 pm 9:00 am – 9:30 am 1. PQ’s People Mix it Up! 35. Roslyn Rutabaga 9:00 am – 10:30 am Thursday, September 23 36. Novel Architecture with Lisa Moore at a glance 10:00 am – 10:45 am 9:00 am – 10:00 am 37. Travels with my Family 2. In Pursuit of Global Justice Festival Onstage Writers Studio 38. Breakfast at the Exit Cafe Launch FREE 3. Your Backyard, 2050 Grand Theatre Onstage Free Events 11:00 am – 12:00 noon 9:00 am – 10:30 am 39. Fantastic Fiction 4. Words Out Loud with Lara Bozabalian Food & Book Lovers Event 40. Married, with Manuscripts 10:30 am – 11:30 am 5. Starting Young 11:00 am – 12:30 pm Friday, September 24 41. Found Fiction with Michael Winter 6. In and Out of the Nest 1:00 pm – 2:15 pm 11:00 am – 12:00 noon 9:00 am – 10:00 am 42. Author! Author! 7. BookMark: Bronwen Wallace 20. The Secret Lives of Birds 1:00 pm – 2:00 pm 11:30 am – 1:00 pm 10:30 am – 12:00 noon 43. Paul Quarrington Life in Music LitDoc screening FREE 9. Book Lovers’ Lunch Chez Piggy 21. Past Perfect 3:00 pm – 4:30 pm 12:00 pm – 1:00 pm 22. Penprick of Conscience 44. Tales from the Rock 8. Paul Quarrington Life in Music LitDoc screening FREE 23. Poetry Beyond the Page with Jill Battson 45. Poets: Stage vs. -

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018 www.scotiabankgillerprize.ca # The Boys in the Trees, Mary Swan – 2008 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, Mona Awad - 2016 Brother, David Chariandy – 2017 419, Will Ferguson - 2012 Burridge Unbound, Alan Cumyn – 2000 By Gaslight, Steven Price – 2016 A A Beauty, Connie Gault – 2015 C A Complicated Kindness, Miriam Toews – 2004 Casino and Other Stories, Bonnie Burnard – 1994 A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry – 1995 Cataract City, Craig Davidson – 2013 The Age of Longing, Richard B. Wright – 1995 The Cat’s Table, Michael Ondaatje – 2011 A Good House, Bonnie Burnard – 1999 Caught, Lisa Moore – 2013 A Good Man, Guy Vanderhaeghe – 2011 The Cellist of Sarajevo, Steven Galloway – 2008 Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood – 1996 Cereus Blooms at Night, Shani Mootoo – 1997 Alligator, Lisa Moore – 2005 Childhood, André Alexis – 1998 All My Puny Sorrows, Miriam Toews – 2014 Cities of Refuge, Michael Helm – 2010 All That Matters, Wayson Choy – 2004 Clara Callan, Richard B. Wright – 2001 All True Not a Lie in it, Alix Hawley – 2015 Close to Hugh, Mariana Endicott - 2015 American Innovations, Rivka Galchen – 2014 Cockroach, Rawi Hage – 2008 Am I Disturbing You?, Anne Hébert, translated by The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Wayne Johnston – Sheila Fischman – 1999 1998 Anil’s Ghost, Michael Ondaatje – 2000 The Colour of Lightning, Paulette Jiles – 2009 Annabel, Kathleen Winter – 2010 Conceit, Mary Novik – 2007 An Ocean of Minutes, Thea Lim – 2018 Confidence, Russell Smith – 2015 The Antagonist, Lynn Coady – 2011 Cool Water, Dianne Warren – 2010 The Architects Are Here, Michael Winter – 2007 The Crooked Maid, Dan Vyleta – 2013 A Recipe for Bees, Gail Anderson-Dargatz – 1998 The Cure for Death by Lightning, Gail Arvida, Samuel Archibald, translated by Donald Anderson-Dargatz – 1996 Winkler – 2015 Curiosity, Joan Thomas – 2010 A Secret Between Us, Daniel Poliquin, translated by The Custodian of Paradise, Wayne Johnston – 2006 Donald Winkler – 2007 The Assassin’s Song, M.G. -

Fifty Short Sermons by T

FIFTY SHORT SERMONS BY T. De WITT TALMAGE COMPILED BY HIS DAUGHTER MAY TALMAGE NEW ^SP YORK GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY TUB NBW YO«K PUBUC LIBRARY O t. COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY 1EW YO:;iC rUbLiC LIBRMIY ASTOR, LENOX AND TILDEN FOUNDATIONS R 1025 L FIFTY SHORT SERMONS BY T. DE WITT TALMAGE. II PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA y CONTENTS I The Three Crosses II Twelve Entrances . III Jordanic Passage . IV The Coming Sermon V Cloaks for Sin /VI The Echoes . VII A Dart through the Liver VIII The Monarch of Books . JX The World Versus the Soul ^ X The Divine Surgeon XI Music in Worship . XII A Tale Told, or, The Passing Years XIII What Were You Made For? XIV Pulpit and Press . XV Hard Rowing . XVI NoontiGe of Life . XVII Scroll oi Heroes XVIII Is Life Worth Living? , XIX Grandmothers , ,. j.,^' XX The Capstoii^''''' '?'*'''' XXI On Trial .... XXII Good Qame Wasted XXIII The Sensitiveness of Christ XXIV Arousing Considerations Ti CONTENTS PAGE XXV The Threefold Glory of the Church . 155 XXVI Living Life Over Again 160 XXVII Meanness of Infidelity 163 XXVIII Magnetism of Christ 168 XXIX The Hornet's Mission 176 XXX Spicery of Religion 182 XXXI The House on the Hills 188 XXXII A Dead Lion 191 XXXIII The Number Seven 196 XXXIV Distribution of Spoils 203 XXXV The Sundial of Ahaz 206 XXXVI The Wonders of the Hand . .210 XXXVII The Spirit of Encouragement . .218 XXXVIII The Ballot-Box 223 XXXIX Do Nations Die? 229 XL The Lame Take the Prey . -

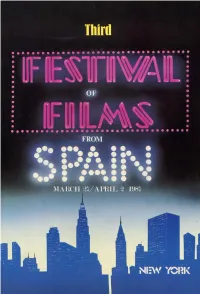

NIEW YORK Third

Third MARCH 27/ APRIL 2 1987 NIEW YORK Third SPAIN IN NEW YORK MARCH 27/APEIL 3 1987 THE GUILD 50»h ST. THEATER (ROCKEFELLER PLAZA) Puntual a la ata, un año más, el "Festival de Cine Español" se presenta en Nueva York, como una embajada de la cinematografía de nuestro país. Este año hemos ampliado hasta catorce el número de películas que se proyectarán. Catorce títulos de un año de producción, sobre un total de sesenta, constituyen, en mi opinión, una muestra muy representativa de la temporada cinematográfíca española 198&87. Una temporada que me atrevo a calificar de esperanzadora en el difícil pero interesante y personal camino que el cine español está recorriendo desde la instauración de la libertad creadora1. Un camino que no ha sido fácil de recorrer, y en el que nuestro cine ha emprendido la dura tarea de reencontrarse a sí mismo, abiertamente, decididamente, después de tantos años de ambigüedad, de falsas y tortuosas fórmulas. Pocas artes como la cinematografía son capaces de reflejar en forma tan puntual la idiosincrasia de un país, su problemática sociopolítica, su cultura. Yo espero que esta películas que hoy ofrecemos puedan acercarles a la imagen de una nación que intenta mostrar al mundo su capacidad creadora, sus valores artísticos, que, enraizados en el pasado, pretenden integrarse, con personalidad propia, en el conjunto universal de búsqueda de nuevas formas. JAVIER SOLANA MADARIAGA Ministro de Cultura IV Once again, for the third time in recent years, we are pleased to present the Festival of Films from Spain in Flew York, representing a kind of embassy of the motion picture industry from our country.