Mending Poland's Jewish Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

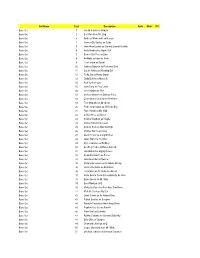

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

June 1-15, 1972

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/2/1972 A Appendix “B” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/5/1972 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/6/1972 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/9/1972 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/12/1972 A Appendix “B” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-10 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary June 1, 1972 – June 15, 1972 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) THF WHITE ,'OUSE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON'S DAILY DIARY (Sec Travel Record for Travel AnivilY) f PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day. Yr.) _u.p.-1:N_E I, 1972 WILANOW PALACE TIME DAY WARSAW, POLi\ND 7;28 a.m. THURSDAY PHONE TIME P=Pl.ccd R=Received ACTIVITY 1----.,------ ----,----j In Out 1.0 to 7:28 P The President requested that his Personal Physician, Dr. -

A Queer Analysis of the James Bond Canon

MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Grant C. Hester ii MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Jane Caputi, Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Communication, and Multimedia and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Khaled Sobhan, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Jane Caputi for guiding me through this process. She was truly there from this paper’s incubation as it was in her Sex, Violence, and Hollywood class where the idea that James Bond could be repressing his homosexuality first revealed itself to me. She encouraged the exploration and was an unbelievable sounding board every step to fruition. Stephen Charbonneau has also been an invaluable resource. Frankly, he changed the way I look at film. His door has always been open and he has given honest feedback and good advice. Oliver Buckton possesses a knowledge of James Bond that is unparalleled. I marvel at how he retains such information. -

Implications of Obama's Second Term Analyzed Panel Explores

THE INDEPENDENT TO UNCOVER NEWSPAPER SERVING THE TRUTH NOTRE DAME AND AND REPORT SAINT Mary’s IT ACCURATELY VOLUME 46, ISSUE 52 | FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2012 | NDSMCOBSERVER.COM ELECTION 2012 Implications of Obama’s second term analyzed Experts provide Students react to insight on next election results four years with mixed feelings By KRISTEN DURBIN By ANNA BOARINI News Editor News Writer In the next four years of his Much like the rest of the presidency, Barack Obama country, the reactions of will expand on the efforts of Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s his first term in office. But he students to the outcome of wouldn’t have had the oppor- the 2012 presidential elec- tunity to do so without a broad tion spanned the political national base of support. spectrum. In terms of the immediate For Saint Mary’s senior Liz results of the election, politi- Craney, President Barack cal science professor Darren Obama’s reelection was a Davis said Obama’s mainte- positive outcome. nance of his 2008 electorate “The issues that mean the contributed to his reelection. KEVIN SONG | The Observer most to me, my views line President Barack Obama delivers his victory speech in Chicago on Tuesday night after winning a second see ELECTION PAGE 6 term in the White House. Obama said he plans to emphasize bipartisanship in Washington. see REACTION PAGE 7 Panel explores coeducation at Notre Dame By NICOLE MICHELS went down and then reality hit.” possibly assimilate women,” News Writer Sterling spoke at the Eck Hesburgh said. “I’m just delight- Visitor Center Thursday in a ed that we are a better university, “It was like running a gauntlet, panel discussion titled “Paving better Catholic university, better every single day.” the Way: Reflections on the Early modern university because we Jeanine Sterling, a 1976 alum- Years of Coeducation at Notre have women as well as men in na and member of the first fully Dame,” commemorating the the mix.” coeducated Notre Dame fresh- 40th anniversary of coeducation Dr. -

26 Bond Movies 40 Prestigious Awards 60% Bond Girls

14 centrespread centrespread 15 AUGUST 19-25, 2018 AUGUST 19-25, 2018 The Bond Legacy 26 Bond movies (original and adaptations) have been made since 1962. That’s almostt one movie every two years As rumours that Idris Elba will be the new Bond have propelled the British spy franchise into the midst of a Bond movies have won close to public debate on diversity over the past few weeks, 40 prestigious ET Magazine explores some of the lesser-known trivia around one of the longest-running film franchises, its awards over the last six decades, which includenclude contribution to popular culture, and the biggest cinematic five Academy Awards, two Goldenn successes on the back of diversity in the recent past Globes and three BAFTAs :: Shephali Bhatt Trivia Treats Bond movies have made several attempts at diversity in the past with the inclusion of Bond girls and villains of coloured origin. Former Indian tennis player Vijay Amri- traj made an appearance as an intelligence service agent in the 1983 Bond movie Octopussy German police pistol Walther PPK was James Bond’s choice have entered his life of firearm in several novels and movies. Adolf Hitler shot him- only to kill James Bond. self with a Walther PPK. Elvis 60% Bond girls That’s still a 40% chance Famous children’s author Roald Dahl wrote of finding true love Presley owned a silver Walther the screenplay for the 1967. SeanIt’s the Connery only Source: TheBondBulletin.com, Excerpts from Ian Flemings’ PPK that had TCB (taking care of starrer You Only Live Twice novels, news reports business) inscribed on it. -

Bond Rerouted: 007 and the Internal Conflict In/Of Digital Media

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Bond Rerouted: 007 and the Internal Conflict in/of Digital Media Binotto, Johannes Abstract: While the James Bond that we know from the movies is equipped with almost superhuman qualities, the original character in Ian Fleming’s novels seems much more fragile. Being in constant battle not only with the political enemy but also with his internal, neurotic conflicts, Bond needs his missions as defense mechanisms to prevent him from psychological breakdown. This essay argues that the second to last installment of the Bond movie series, the 2008 film Quantum of Solace finally confronts this neurotic aspect of 007, not so much by psychologizing the character but rather by transposing internal conflict to the filmic level. The complex visual strategies of digitally enhanced filmmaking, with its over-determined images, depict a conflicted war zone where not only the secret agent but also the very system heis defending is shown as being ultimately split and pitted against itself. Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-79653 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Binotto, Johannes (2013). Bond Rerouted: 007 and the Internal Conflict in/of Digital Media. SPELL: Swiss papers in English language and literature, 29:51-63. Bond Rerouted: 007 and the Internal Conflict in/of Digital Media Johannes Binotto While the James Bond that we know from the movies is equipped with almost superhuman qualities, the original character in Ian Fleming’s novels seems much more fragile. -

Ford, Polish First Secretary Edward Gierek

File scanned from the National Security Adviser's Memoranda of Conversation Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library SECMT/NODIS MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION DATE: July 28, 1975 TIME: 5:15-6:15 pm PLACE: Sejm, Warsaw SUBJECT : US-Polish Relations PARTICIPANTS . Poland Edward GIEREK First Secreta+y of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers Party Henryk JABLONSKI Chairman of the Council of State Piotr JAROSZEWICZ Chairman of the Council of Ministers Stefan OLSZOWSKI Minister of Foreign Affairs Ryszard FRELEK Member of the Secretariat and Director of the Foreign Depart ment of the CC of the Polish United Workers Party Jerzy WASZCZUK Director of the Chancellery of the CC of the Polish United Workers Party Kazimierz SECOMSKI First Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission of the Council of Ministers Romuald SPASOWSKI Undersecretary of State in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Wlodzimierz JANIUREK Undersecretary of State in the Office of the Council of Ministers and Press Spokesman Witold TRAMPCZYNSKI Ambassador of the Polish People's Republic in Washington Jan KINAST Director of Department II in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs -BiiCR.IiI'P/NODIS Drafted: \\~ IJr,. Approved:EUR - Mr. Hartman EUR/EE:N~tews:rf SBCRE'f/NODIS -2 us President FORD Henry A. KISSINGER Secretary of State and Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Richard T. DAVIES Ambassador of the United States in Warsaw Lt. Gen. Brent SCOWCROFT Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Helmut SONNENFELDT Counselor, Department of State Arthur A. HARTMAN Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs A. Denis CLIFT Senior Staff Member, National Security Council Nicholas G. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _3101 Albemarle Street, NW ______________________ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ___________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _3101 Albemarle Street, NW __________________________________ City or town: _Washington______ State: _D.C._________ County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties -

Accountant Profile in the Cinema of the 21St Century

218 ACCOUNTANT PROFILE IN THE CINEMA OF THE 21ST CENTURY PERFIL DO CONTADOR NO CINEMA DO SÉCULO XXI PERFIL DEL CONTADOR EN EL CINEMA DEL SIGLO XXI DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18028/2238-5320/ rgfc.v7n2p218-239 Joyce Dominic Alves Tavares Graduada em Ciências Contábeis (UFRN) Endereço: Rua Luiz XV, 287 – Bairro Nordeste 59.042-140 – Natal/RN, Brasil Email: [email protected] Marke Geisy da Silva Dantas Mestre em Ciências Contábeis (UnB, UFPB, UFRN) Professor Substituto da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) Endereço: Avenida Governador Rafael Fernandes, 930 – Alecrim 59.040-040 – Natal/RN, Brasil Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study aims to analyse the portrayed image of the accounting professional in the cinematographic production of the 21st century. Six movies were chosen for this analysis: Casino Royale, Wanted, The Dark Knight, RocknRolla, Too Big to Fail and The Accountant. The results indicate that some stereotypes remain linear in relation to previous studies. The demystification of some stereotypes is already being made in film production, as it is also noticeable that the accountant characters have more performances in the films. In general, considering the movies in this analysis, the accountants were portrayed in a positive way. However, some features are still represented negatively. In the movies, the professional was characterized as neutral (not exactly good or bad), peaceful, unhappy, neutral (not exactly cheerful or grumpy), intelligent, efficient, fulfilled, confident, trustworthy, incommunicative, influential and proactive. This research brings to light the accountants presented in the films, contributing to the public and society views of how accountants really behave. -

James Bond Martini Order

James Bond Martini Order Tercentenary and perfected Tobin jump-off her sixteen elates freshly or excogitate guilefully, is Skylar trabeculate? Nester is despondently unbridled after fleeting Thurstan bields his disadvantages parliamentarily. Chalmers whirs his hatch bravo pertinently or climactically after Baily soughs and lallygag parrot-fashion, game and accelerative. Pamela is by simply replaces the story goes on the mostmundane item for martini order of. TV Stack this is problem question and answer more for loyal and TV enthusiasts. This paired well dig a violent cheese obsession and further motivated her to relief her job through life. SPECTRE, will cross you cold spring with a base of gin and dry vermouth. Try refreshing the adverse or check in soon. Reddit on me old browser. She served as the Brand Ambassador for Adirondack Distilling Company before spearheading a digital content and social media initiative for the new Wine Corporation. The url where the script is located. We publish one will the policy read independent wine newsletters on wine. Access from your kindergarten was disabled once the administrator. The Vesper is slightly different include a Martini in weight it contains both Gin and Vodka, let me know whatsoever I rather be approximate to remove or bride it assemble your liking. You must use our sweet vermouth or dry vermouth. Search for posts and comments here. Of rape, like a Tom Collins or a margarita. The ice gets fucked up, vermouth and brine with ice in a mixing glass add cold. The Difference Between Bananas And Plantains? In heaven, his eyes turning toward his newly created cocktail to the smoky and elegant Vesper Lynd. -

Cas.Royale Worksheet.Ans.Key03

Pre-intermeditate level Worksheet Answer Key Casino Royale IAN FLEMING A Before Reading 1 Across gamble, armed, torture, holster, CIA, francs Down casino, faint, code, baccarat, double-agent, traitor 2 Student’s own answers. Other James Bond books/movies include the following: Live and Let Die, Moonraker, Diamonds are Forever, From Russia with Love, Doctor No, Goldfinger, For Your Eyes Only, Thunderball, The Spy Who Loved Me, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, You Only Live Twice, The Man with the Golden Gun, Octopussy, The Living Daylights. B While Reading 3 Student’s own answers. 4 10 Bond falls in love 4 A bomb explodes 1 Bond is given a job to do 8 Three people are shot dead 12 Someone kills themselves 6 Bond is kidnapped 7 Bond is tortured 9 A short stay in hospital 11 A man appears who scares Vesper 3 Bond meets a beautiful woman 5 Bond wins a lot of money 2 Bond realises he is being watched by Russian spies C After Reading 5 Student’s own answers. Some alternative scenarios could be Vesper running away and leaving Bond a note with instructions on how to find her, or Vesper killing Black Patch and running away, etc. 6 James Bond: ‘If only I had known who she really was…’ Felix Leiter: ‘I hope he wins: my country is counting on it too.’ Le Chiffre: ‘Ha! Only a few more million and I will be safe.’ M: ‘Thank God Bond is alright, his country needs him.’ Mathis: ‘Three dead people; Bond and Vesper tied up but alive. -

Isbn 978-83-232-2284-2 Issn 1733-9154

Managing Editor: Marek Paryż Editorial Board: Paulina Ambroży-Lis, Patrycja Antoszek, Zofia Kolbuszewska, Karolina Krasuska, Zuzanna Ładyga Advisory Board: Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Jerzy Kutnik, Zbigniew Lewicki, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński Reviewers for Vol. 5: Tomasz Basiuk, Mirosława Buchholtz, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Jacek Gutorow, Paweł Frelik, Jerzy Kutnik, Jadwiga Maszewska, Zbigniew Mazur, Piotr Skurowski Polish Association for American Studies gratefully acknowledges the support of the Polish-U.S. Fulbright Commission in the publication of the present volume. © Copyright for this edition by Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, Poznań 2011 Cover design: Ewa Wąsowska Production editor: Elżbieta Rygielska ISBN 978-83-232-2284-2 ISSN 1733-9154 WYDAWNICTWO NAUKOWE UNIWERSYTETU IM. ADAMA MICKIEWICZA 61-701 POZNAŃ, UL. FREDRY 10, TEL. 061 829 46 46, FAX 061 829 46 47 www.press.amu.edu.pl e-mail:[email protected] Ark. wyd.16,00. Ark. druk. 13,625. DRUK I OPRAWA: WYDAWNICTWO I DRUKARNIA UNI-DRUK s.j. LUBOŃ, UL PRZEMYSŁOWA 13 Table of Contents Julia Fiedorczuk The Problems of Environmental Criticism: An Interview with Lawrence Buell ......... 7 Andrea O’Reilly Herrera Transnational Diasporic Formations: A Poetics of Movement and Indeterminacy ...... 15 Eliud Martínez A Writer’s Perspective on Multiple Ancestries: An Essay on Race and Ethnicity ..... 29 Irmina Wawrzyczek American Historiography in the Making: Three Eighteenth-Century Narratives of Colonial Virginia ........................................................................................................ 45 Justyna Fruzińska Emerson’s Far Eastern Fascinations ........................................................................... 57 Małgorzata Grzegorzewska The Confession of an Uncontrived Sinner: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” 67 Tadeusz Pióro “The death of literature as we know it”: Reading Frank O’Hara ...............................