Medieval Dundee I Have Been Fortunate in the Assistance Given by Many People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WCDC2019 Book of Abstracts

Contents Oral Presentations Pages 3-65 Practice Workshops Pages 66-88 Film Screenings Pages 89-93 Installations/Artistic Responses Pages 94-95 Posters Pages 96-103 Unconference Afternoon Pages 104-105 Please Note: All abstracts are listed in alphabetical order based on the first letter of the author’s surname. If there is more than one author, the abstract will be listed under the surname of the first author as listed in the Conference Programme. 2 age P Oral Presentations Malath Abbas – BiomeCollective Digital Collaboration and Communities Malath Abbas is an independent game designer, artist and producer working on experimental and meaningful games. Malath is establishing Scotland's first game collective and co-working space Biome Collective, a diverse, inclusive melting pot of technology, art and culture for people who want to create, collaborate and explore games, digital art and technology. Projects includes Killbox, an online game and interactive installation that critically explores the nature of drone warfare, its complexities and consequences, and Hello World the sound and lightshow that opened up V&A Dundee. Malath will explore digital physical communities as well as games for good. Aileen Ackland, Pamela Abbott, Peter Mtika - University of Aberdeen Missives from a front line of global literacy wars This presentation will analyse the tensions inherent in a Scottish/Rwanda collaborative project to develop a social practices approach to adult literacies education in the Western Province of Rwanda. A social practices perspective acknowledges the significance of social purpose, place and power to literacies. It counters the traditional view of literacy assumed within international development goals which focus on reducing national rates of ‘illiteracy’. -

3 Whitenhill, Tayport, Fife, DD6 9BZ

Let’s get a move on! 3 Whitenhill, Tayport, Fife, DD6 9BZ www.thorntons-property.co.uk Conversion of a former public house has created two stylish townhouses • Spacious Lounge/Dining DD6 9BZ Fife, 3 Whitenhill, Tayport, in a prime central location within the harbour area at Tayport. This Area Listed C Building has been attractively converted and incorporates quality specifications and fitments throughout. The subject property is • Quality Kitchen Area the left hand example of these 2 storey, semi detached townhouses. • Ground Floor Family An attractive entrance door leads to an impressive entrance hallway where there are double leaf glass doors through to the lounge and a Bathroom door to the family bathroom. There is a feature staircase to the upper • 2 Double Bedrooms floor accommodation with attractive glass panelling incorporated. The hallway incorporates attractive designer radiators. The staircase • Shower Room/1 En Suite The property benefits from gas central and upper floor area are carpeted and the ground floor has feature • Gas Central Heating heating and double glazing. The windows engineered oak floors. The open planned lounge and dining area at have been manufactured to echo the ground floor level has a spacious, well appointed kitchen located off. • Double Glazing original sash and case style windows The kitchen incorporates Cathedral style ceiling with velux windows which have been replaced and retain the and quality work surfaces, splashback tiling and integrated appliances • Engineered Oak Flooring & character of this impressive building. are included. A door from the kitchen leads to a private lane to the rear • Carpets The property is convenient for all central which gives way to the private garden ground which has Astro style turf amenities and services in Tayport, whilst and rotary dryer in place. -

Draft Amended Citation

Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the conservation of wild birds (this is the codified version of Directive 79/409/EEC as amended) CITATION FOR SPECIAL PROTECTION AREA (SPA) FIRTH OF TAY AND EDEN ESTUARY (UK9004121) Site Description: The Firth of Tay and Eden Estuary SPA is a complex of estuarine and coastal habitats in eastern Scotland from the mouth of the River Earn in the inner Firth of Tay, east to Barry Sands on the Angus coast and St Andrews on the Fife coast. For much of its length the main channel of the estuary lies close to the southern shore and the most extensive intertidal flats are on the north side, west of Dundee. In Monifieth Bay, to the east of Dundee, the substrate becomes sandier and there are also mussel beds. The south shore consists of fairly steeply shelving mud and shingle. The Inner Tay Estuary is particularly noted for the continuous dense stands of common reed along its northern shore. These reedbeds, inundated during high tides, are amongst the largest in Britain. Eastwards, as conditions become more saline, there are areas of saltmarsh, a relatively scarce habitat in eastern Scotland. The boundary of the SPA is contained within the following Sites of Special Scientific Interest: Inner Tay Estuary, Monifieth Bay, Barry Links, Tayport -Tentsmuir Coast and Eden Estuary. Qualifying Interest N.B All figures relate to numbers at the time of classification: The Firth of Tay and Eden Estuary SPA qualifies under Article 4.1 by regularly supporting populations of European importance of the Annex I species: marsh harrier Circus aeruginosus (1992 to 1996, an average of 4 females, 3% of the GB population); little tern Sternula albifrons (1993 to1997, an average of 25 pairs, 1% of the GB population) and bar-tailed godwit Limosa lapponica (1990/91 to 1994/95, a winter peak mean of 2,400 individuals, 5% of the GB population). -

St Andrews Town

27 29 A To West Sands 28 9 St Andrews 1 to THE SC 1 D O u THE LINK S RES Town Map n 22a 54 de 32 41 42 e BUTT a Y PK 30 43 nd L S 0 100m 200m 300m euc 33 40 W YND 44 55 hars NO 31 53 22 MURRA C R 19 TH S 34 35 56 I BOTSFOR TREE T B D 39 46 SCALE 20 A CR T 30a 45 57 Y T 36 North 2 18 RO 38 47 51 Haugh 48 49 A ST 31b 75a 17 21 T 50 D HOPE ST 60 52 58 N CASTLE S 75b 11 16 23 COLLEGE 4 GREYFRIARS GDNS 59 UNION S 3 ET STRE ET CHURCH S 15 ST MARY’S PLACE MARK 12 BELL STRE 62 61 75 D 85 10 Kinburn OA 24 25 Pier R S T 76 14 Park KE 3 5 13 Y ET 79 D 26 67 66 LE ET ABBEY ST 77 B 33a WESTBURN All Weather U 65 THE PENDS O SOUTH63 STRE QUEENS GARDEN Pitches & D Y GARDENS Running W 78 AR 9 TREET 68 74 Track DL ARGYLE S 64 69 LANE 8 KENNED AW DO G D N N B E ST LEONARD’S A S C L R A 4 D L SO ID 70 P A N S BBEY G E G S 71 D E ID N 70a W Playing S ALK 6 S ST 72 N Fields RO E E AC E R TERR 1 AD QUEENS EE 73 R 80 2 G T East Sands HEPBURN GARDEN KI Community 7 NNE 5 Garden SSB 81 U L Botanic R N A R D N S S BUCHANAN GARDEN Garden GLAN T NS M E A DE D 82 R U R A S N Y G E R N UR V D S T 83 PB A R E VENU E 6 H A E S N E SO E T AT OA W B Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2010 . -

Dundeeuniversi of Dundee Undergraduate Prospectus 2019

This is Dundee Universi of Dundee Undergraduate Prospectus 2019 One of the World’s Top 200 Universities Times Higher Education World Universi Rankings 2018 This is Dundee Come and visit us Undergraduate open days 2018 and 2019 Monday 27 August 2018 Saturday 22 September 2018 Monday 26 August 2019 Saturday 21 September 2019 Talk to staff and current students, tour our fantastic campus and see what the University of Dundee can offer you! Booking is essential visit uod.ac.uk/opendays-ug email [email protected] “It was an open day that made me choose Dundee. The universities all look great and glitzy on the prospectus but nothing compares to having a visit and feeling the vibe for yourself.” Find out more about why MA Economics and Spanish student Stuart McClelland loved our open day at uod.ac.uk/open-days-blog Contents Contents 8 This is your university 10 This is your campus 12 Clubs and societies 14 Dundee University Students’ Association 16 Sports 18 Supporting you 20 Amazing things to do for free (or cheap!) in Dundee by our students 22 Best places to eat in Dundee – a students’ view 24 You’ll love Dundee 26 Map of Dundee 28 This is the UK’s ‘coolest little city’ (GQ Magazine) 30 Going out 32 Out and about 34 This is your home 38 This is your future 40 These are your opportunities 42 This is your course 44 Research 46 Course Guide 48 Making your application 50 Our degrees 52 Our MA honours degree 54 Our Art & design degrees 56 Our life sciences degrees 58 Studying languages 59 The professions at Dundee 60 Part-time study and lifelong learning 61 Dundee is international 158 Advice and information 160 A welcoming community 161 Money matters 162 Exchange programmes 164 Your services 165 Where we are 166 Index 6 7 Make your Make This is your university This is your Summer Graduation in the City Square Summer Graduation “Studying changes you. -

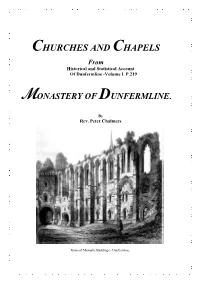

Churches and Chapels Monastery

CHURCHES AND CHAPELS From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline -Volume I. P.219 MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE. By Rev. Peter Chalmers Ruins of Monastic Buildings - Dunfermline. A REPRINT ON DISC 2013 ISBN 978-1-909634-03-9 CHURCHES AND CHAPELS OF THE MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE FROM Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline Volume I. P.219 By Rev. Peter Chalmers, A.M. Minister of the First Charge, Abbey Church DUNFERMLINE. William Blackwood and Sons Edinburgh MDCCCXLIV Pitcairn Publications. The Genealogy Clinic, 18 Chalmers Street, Dunfermline KY12 8DF Tel: 01383 739344 Email enquiries @pitcairnresearh.com 2 CHURCHES AND CHAPELS OF THE MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE. From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline Volume I. P.219 By Rev. Peter Chalmers The following is an Alphabetical List of all the Churches and Chapels, the patronage which belonged to the Monastery of Dunfermline, along, generally, with a right to the teinds and lands pertaining to them. The names of the donors, too, and the dates of the donation, are given, so far as these can be ascertained. Exact accuracy, however, as to these is unattainable, as the fact of the donation is often mentioned, only in a charter of confirmation, and there left quite general: - No. Names of Churches and Chapels. Donors. Dates. 1. Abercrombie (Crombie) King Malcolm IV 1153-1163. Chapel, Torryburn, Fife 11. Abercrombie Church Malcolm, 7th Earl of Fife. 1203-1214. 111 . Bendachin (Bendothy) …………………………. Before 1219. Perthshire……………. …………………………. IV. Calder (Kaledour) Edin- Duncan 5th Earl of Fife burghshire ……… and Ela, his Countess ……..1154. V. Carnbee, Fife ……….. ………………………… ……...1561 VI. Cleish Church or……. Malcolm 7th Earl of Fife. -

Friends of Dundee Law Welcome Pack

Friends of Dundee Law Welcome pack With its breath taking views across the city, historical features and tranquil woodland walks, the Law is a special place, treasured by Dundonians of all ages. The Dundee TWIG project agrees that the Law is a fantastic green space and feel that local people should have a greater involvement in what happens on the Law and play a vital role in its management and development. In order to help local people become more involved in positive action on the Law, we are looking to form a Friends of Dundee Law group. Anyone with an interest in the Law is welcome to join the group which will be supported by the Council’s Environment Department and Community Officers. To kick start the project, Forestry Commission Scotland have provided a grant through the Community Seedcorn Fund. This will support the group’s activities and events throughout the first year. Additionally, the Environment Department are currently putting together a Law Masterplan. This will contain an array of proposed environmental improvements i.e. path & steps restoration and woodland management, and also enhancing the heritage of the site for the public to enjoy. If after reading this welcome pack you would like to join the Friends of Dundee Law or are interested in finding out more please contact Jen Thomson. Contact details can be found on the back page of this pack . !n introduction to the Dundee Law The Dundee Law is a popular urban green space and prominent feature on the Dundee skyline. There is approximately 8.25ha of woodland with additional areas of open ground which greatly contribute in providing wildlife habitat and recreational opportunities. -

A4 Paper 12 Pitch with Para Styles

REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE ACT 1983 NOTICE OF CHANGES OF POLLING PLACES within Fife’s Scottish Parliamentary Constituencies Fife Council has decided, with immediate effect to implement the undernoted changes affecting polling places for the Scottish Parliamentary Election on 6th May 2021. The premises detailed in Column 2 of the undernoted Schedule will cease to be used as a polling place for the polling district detailed in Column 1, with the new polling place for the polling district being the premises detailed in Column 3. Explanatory remarks are contained in Column 4. 1 2 3 4 POLLING PREVIOUS POLLING NEW POLLING REMARKS DISTRICT PLACE PLACE Milesmark Primary Limelight Studio, Blackburn 020BAA - School, Regular venue Avenue, Milesmark and Rumblingwell, unsuitable for this Parkneuk, Dunfermline Parkneuk Dunfermline, KY12 election KY12 9BQ 9AT Mclean Primary Baldridgeburn Community School, Regular venue 021BAB - Leisure Centre, Baldridgeburn, unavailable for this Baldridgeburn Baldridgeburn, Dunfermline Dunfermline KY12 election KY12 9EH 9EE Dell Farquharson St Leonard’s Primary 041CAB - Regular venue Community Leisure Centre, School, St Leonards Dunfermline unavailable for this Nethertown Broad Street, Street, Dunfermline Central No. 1 election Dunfermline KY12 7DS KY11 3AL Pittencrieff Primary Education Resource And 043CAD - School, Dewar St, Regular venue Training Centre, Maitland Dunfermline Crossford, unsuitable for this Street, Dunfermline KY12 West Dunfermline KY12 election 8AF 8AB John Marshall Community Pitreavie Primary Regular -

A Memorial Volume of St. Andrews University In

DUPLICATE FROM THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND. GIFT OF VOTIVA TABELLA H H H The Coats of Arms belong respectively to Alexander Stewart, natural son James Kennedy, Bishop of St of James IV, Archbishop of St Andrews 1440-1465, founder Andrews 1509-1513, and John Hepburn, Prior of St Andrews of St Salvator's College 1482-1522, cofounders of 1450 St Leonard's College 1512 The University- James Beaton, Archbishop of St Sir George Washington Andrews 1 522-1 539, who com- Baxter, menced the foundation of St grand-nephew and representative Mary's College 1537; Cardinal of Miss Mary Ann Baxter of David Beaton, Archbishop 1539- Balgavies, who founded 1546, who continued his brother's work, and John Hamilton, Arch- University College bishop 1 546-1 57 1, who com- Dundee in pleted the foundation 1880 1553 VOTIVA TABELLA A MEMORIAL VOLUME OF ST ANDREWS UNIVERSITY IN CONNECTION WITH ITS QUINCENTENARY FESTIVAL MDCCCCXI MCCCCXI iLVal Quo fit ut omnis Votiva pateat veluti descripta tabella Vita senis Horace PRINTED FOR THE UNIVERSITY BY ROBERT MACLEHOSE AND COMPANY LIMITED MCMXI GIF [ Presented by the University PREFACE This volume is intended primarily as a book of information about St Andrews University, to be placed in the hands of the distinguished guests who are coming from many lands to take part in our Quincentenary festival. It is accordingly in the main historical. In Part I the story is told of the beginning of the University and of its Colleges. Here it will be seen that the University was the work in the first instance of Churchmen unselfishly devoted to the improvement of their country, and manifesting by their acts that deep interest in education which long, before John Knox was born, lay in the heart of Scotland. -

MD17 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

MD17 bus time schedule & line map MD17 St Andrews, Madras College - Tayport, Queen View In Website Mode Street The MD17 bus line St Andrews, Madras College - Tayport, Queen Street has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Tayport: 4:07 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest MD17 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next MD17 bus arriving. Direction: Tayport MD17 bus Time Schedule 59 stops Tayport Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:07 PM New Madras College, St Andrews Tuesday 5:07 PM Strathtyrum Golf Course, St Andrews Wednesday 4:07 PM Easter Kincaple Farm, Kincaple Thursday 5:07 PM Edenside, Kincaple Friday 2:37 PM Guardbridge Hotel, Guardbridge Saturday Not Operational Mills Building, Guardbridge Ashgrove Buildings, Guardbridge MD17 bus Info Innerbridge Street, Guardbridge Direction: Tayport Stops: 59 Innerbridge Street, Scotland Trip Duration: 70 min Line Summary: New Madras College, St Andrews, Toll Road, Guardbridge Strathtyrum Golf Course, St Andrews, Easter Kincaple Farm, Kincaple, Edenside, Kincaple, Station Road, Leuchars Guardbridge Hotel, Guardbridge, Mills Building, Guardbridge, Ashgrove Buildings, Guardbridge, St Bunyan's Place, Leuchars Innerbridge Street, Guardbridge, Toll Road, Guardbridge, Station Road, Leuchars, St Bunyan's Fern Place, Leuchars Place, Leuchars, Fern Place, Leuchars, Cemetery, A919, Leuchars Leuchars, Castle Farm Road End, Leuchars, Dundee Road, St Michaels, Inn, Pickletillem, National Golf Cemetery, Leuchars Centre, Drumoig, Forgan -

50 Ways to Xplore Dundee This Christmas

50 Ways to Xp lore D undee this C hristmas Also inside: bus service level arrangements over the holiday period Bus Service & Travel Centre Arrangements Date Travel Centre Hours Bus Service Levels Saturday 23 December 0900 - 1600 Normal (Saturday) service Sunday 24 December closed Normal (Sunday) service - see last buses below Monday 25 December closed No service Tuesday 26 December closed Sunday service - see last buses below Wednesday 27 December 1000 - 1600 Normal (weekday) service to Friday 29 December Saturday 30 December 1000 - 1600 Normal (Saturday) service Sunday 31 December closed Normal (Sunday) service - see last buses below Monday 1 January closed No service Tuesday 2 January closed Sunday service - see last buses below Wednesday 3 January 0900 - 1700 Normal (weekday) service resumes for 2018 Last Buses Home 24 Dec 26 Dec 24 Dec 26 Dec 31 Dec 2 Jan 31 Dec 2 Jan Services 1a/1b Full route (from City Centre) Full route (towards City Centre) (1a) City Centre - St Marys 2005 2005 (1a) St Marys - City Centre 2105 2005 (1b) City Centre - St Marys 2035 2035 (1b) St Marys - City Centre 2035 2035 Service 4 Full route (from City Centre) Full route (towards City Centre) (4) City Centre - Dryburgh no service (4) Dryburgh - City Centre no service Services 5* | 9/10 *please note: service 5 changes to services 9a/10a in the evening Full Outer Circle (clockwise) Full Outer Circle (anti-clockwise) (9a) Barnhill - Barnhill 1931 1555 (10a) Ninewells - Ninewells 1940 1710 Full route (towards Ninewells) Full route (from Ninewells) (9a) Barnhill - Ninewells 2101 1918* (10a) Ninewells - Barnhill 2040 2010 *Please note: the 1918 journey from Barnhill will run normal Outer Circle route as far as Whitfield (The Crescent). -

12:34 Pm 12:34 Pm

www.dundee.com 12:34 PM 12:34 PM Download FREE for your Guide to Dundee One City, Many Discoveries www.dundee.com Words people most associate with Dundee: www.dundee.com Dundee is home to one of the most significant biomedical and life sciences communities in the UK outwith Oxford and Cambridge. Dundee has one of the highest student population ratios in the UK. At 1:5 with 50,000 studying within 30 minutes of the city. www.dundee.com Dundee was named the Global video game hits UK’s first UNESCO City Lemmings and Grand of Design by the United Theft Auto were created Nations in 2014. in Dundee. www.dundee.com The City of Design desig- nation has previously been HMS Unicorn is one of the oldest ships afloat in the world. Dundee boasts two 5-star award winning visitor attractions, namely Discovery Point and Scotland’s Jute Museum @ Verdant Works. In addition, other attractions include HMS Unicorn, Dundee Science Centre and Mills Observatory. www.dundee.com a few Broughty Castle Scotland’s Jute Museum Museum @ Verdant 01382 436916 Works 01382 309060 D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum HMS Frigate 01382 384310 Unicorn 01382 200900 The Population Tayside Medical of Dundee is History Museum Dundee Science currently 148,710 01382 384310 Centre with approximately 01382 228800 306,300 people RRS Discovery/ living within a 30 Discovery Point minute drive time. 01382 309060 www.dundee.com “Dundee is a little pot of gold at the end of the A92” - The Guardian Dundee is a cultural hive - both historical and contemporary.